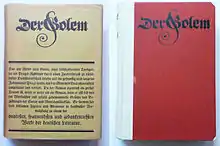

First Edition, Kurt Wolff, Leipzig 1915/16 | |

| Author | Gustav Meyrink |

|---|---|

| Original title | Der Golem |

| Country | Germany |

| Language | German |

| Genre | Fantasy, horror |

| Publisher | Kurt Wolff |

Publication date | 1915 |

The Golem (original German title: Der Golem) is a novel written by Gustav Meyrink between 1907 and 1914.[1] First published in serial form from December 1913 to August 1914[1] in the periodical Die Weißen Blätter, The Golem was published in book form in 1915 by Kurt Wolff, Leipzig. The Golem was Meyrink's first novel. It sold over 200,000 copies in 1915.[2] It became his most popular and successful literary work,[2] and is generally described as the most "accessible" of his full-length novels. It was first translated into English in 1928.

Plot

The novel centers on the life of Athanasius Pernath, a jeweler and art restorer who lives in the ghetto of Prague. But his story is experienced by an anonymous narrator, who, during a visionary dream, assumes Pernath's identity thirty years before. This dream was perhaps induced because he inadvertently swapped his hat with the real (old) Pernath's. While the novel is generally focused on Pernath's own musings and adventures, it also chronicles the lives, the characters, and the interactions of his friends and neighbors. The Golem, though rarely seen, is central to the novel as a representative of the ghetto's own spirit and consciousness, brought to life by the suffering and misery that its inhabitants have endured over the centuries.

The story itself has a disjointed and often elliptical feel, as it was originally published in serial form and is intended to convey the mystical associations and interests that the author himself was exploring at the time. The reality of the narrator's experiences is often called into question, as some of them may simply be dreams or hallucinations, and others may be metaphysical or transcendent events that are taking place outside the "real" world. Similarly, it is revealed over the course of the book that Pernath apparently suffered from a mental breakdown on at least one occasion, but has no memory of any such event; he is also unable to remember his childhood and most of his youth, a fact that may or may not be attributable to his previous breakdown. His mental stability is constantly called into question by his friends and neighbors, and the reader is left to wonder whether anything that has taken place in the narrative actually happened.

Main characters

- Athanasius Pernath: the ostensible protagonist, a jeweler who resides in the ghetto of Prague

- The Golem: while connected with the Golem legend of Rabbi Judah Loew, the Golem is cast as a sort of gestalt entity, a physical manifestation of the ghetto's inhabitants' collective psyche, as well as of the ghetto's own "self".

- Schemajah Hillel: a wise and gentle Jewish neighbor of Pernath, learned in the Torah and Talmud; serves as a protector and instructor for Pernath as the jeweler begins to walk the path of mysticism.

- Miriam: Hillel's compassionate and noble daughter.

- Aaron Wassertrum: another of Pernath's neighbors, this one a junk dealer and possibly a murderer. He is the antithesis of Hillel, embodying all of the then-popular negative stereotypes surrounding Jews.

- Rosina: a 14-year-old red-haired prostitute and neighbor of Pernath, apparently a relation of Wassertrum though no one is ever able to determine what kind; described by Pernath as repulsive, but figures prominently as the object of men's desires and is promiscuous.

- Innocence Charousek: a consumptive, poverty-stricken student consumed with hatred for Wassertrum and his son, Dr. Wassory.

- Zwakh: a puppeteer; Pernath's friend and landlord.

- Amadeus Laponder: Pernath's cellmate in prison. He is a somnambulist who in his sleep assumes the role of various people of the ghetto, allowing Pernath to communicate with the outside world.

- Dr. Savioli: a wealthy neighbor of Pernath's who rents a room in the ghetto from Zwakh; there he carries on illicit affairs with married women.

Minor characters

- The Regiment

- Dr. Wassory

- Angelina

Reception

In his "Supernatural Horror in Literature" essay, H. P. Lovecraft said the novel is one of the "best examples" of Jewish folklore inspired weird fiction.[3] Also, in a letter, he called it, "[t]he most magnificent weird thing I've come across in aeons!"[4]

Dave Langford reviewed The Golem for White Dwarf #80, and stated that "It's the sort of nightmare you might have after an evening of too much lobster and Kafka. Very strange."[5]

The Guardian writer David Barnett said in his article about the novel that it is "one of the most absorbing, atmospheric and mind-boggling slices of fantasy ever committed to print," and "[a] century after its first publication, The Golem endures as a piece of modernist fantasy that deserves to take its place alongside Kafka."[1]

English translations

Since The Golem was first published in German, there have been two translations into English:

- Madge Pemberton (1928): First published by Houghton Mifflin Co. and Victor Gollancz Ltd. Published by Mudra in 1972. Published by Dover Publications in 1976. Published by Dedalus Ltd in 1985. Published by Centipede Press in 2012.

- Mike Mitchell (1995): First published by Ariadne Press. Published by Dedalus Ltd in 2000. Published by Tartarus Press in 2004. Published by Folio Society in 2010.

The Dover Publications edition was edited by E. F. Bleiler, who made some alterations to Pemberton's translation.[6]

Adaptation for film and theatre

The novel was the basis for the following movies:

- Golem, directed by Piotr Szulkin, made in 1979, released in 1980.

- Le Golem (1967), film for television directed by Jean Kerchbron

The novel was adapted for the theatre by Daniel Flint, and received a world premiere in 2013.[7]

However, it was not the basis for three films of the same title by Paul Wegener, which, rather, adapt the original Golem legend:

- The first, The Golem, directed by Paul Wegener, filmed in 1914, released in 1915, has been lost;

- The second, The Golem and the Dancing Girl, directed by Paul Wegener, filmed in 1917, has been lost;

- The third, The Golem: How He Came into the World, directed by Paul Wegener, made in 1920, survives;[8][9][10]

Nor was it the basis for the operas of Eugen d'Albert (Der Golem (opera)) or Nicolae Bretan (Golem (Bretan opera)).

References

- 1 2 3 Barnett, David (January 30, 2014). "Meyrink's The Golem: where fact and fiction collide". The Guardian. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- 1 2 Barnett, David (March 21, 2018). "Gustav Meyrink: The mysterious life of Kafka's contemporary". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2022-06-18. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- ↑ Lovecraft, H. P. . – via Wikisource.

- ↑ Roland, Paul (December 22, 2014). "Lovecraft's Library". Pan MacMillan. Archived from the original on April 23, 2019. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- ↑ Langford, Dave (August 1986). "Critical Mass". White Dwarf. No. 80. Games Workshop. p. 9.

- ↑ Bleiler, E. F. (1976). "Acknowledgements". The Golem. By Meyrink, Gustav. Dover Publications. p. xix. ISBN 9780486250250. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- ↑ Styles, Hunter (May 3, 2013). "The Golem – a bracingly bizarre chiller". DC Theatre Scene.

- ↑ Isenberg, Noah (2009). Weimar Cinema: An Essential Guide to Classic Films of the Era. Columbia University Press. p. 332. ISBN 978-0-231-13055-4.

- ↑ Kellner, Douglas. Passion and Rebellion: The Expressionist Heritage. p. 384.

- ↑ Scheunemann, Dietrich (2003). Expressionist Film: New Perspectives. Camden House. p. 273. ISBN 978-1571133502.

Sources

- Matei Chihaia: Der Golem-Effekt. Orientierung und phantastische Immersion im Zeitalter des Kinos transcript, Bielefeld 2011 ISBN 978-3-8376-1714-6