The Pittsburgh Dispatch was a leading newspaper in Pittsburgh, operating from 1846 to 1923. After being enlarged by publisher Daniel O'Neill it was reportedly one of the largest and most prosperous newspapers in the United States. From 1880 to 1887 native of nearby Cochran's Mills, Nellie Bly worked for the Dispatch writing investigative articles on female factory workers, and later reported from Mexico as a foreign correspondent. The paper was politically independent and was particularly known for its in-depth court reporting.

History

The Foster years

Established by Col. J. Heron Foster, the Dispatch made its first appearance on February 9, 1846.[1] It was the first penny paper published in Western Pennsylvania, initially comprising only four pages. The paper was almost unique in the industry for being profitable almost from the very beginning despite being started during an economic recession.[2]

Foster was a strong opponent of slavery in the United States and, having determined that the local market thought similarly, lent an abolitionist tone to the paper. He was also a strong supporter of women's suffrage. His daughter Rachel Foster Avery became a prominent worker in the National American Woman Suffrage Association. He hired a woman to work in the newsroom and invited the protesting men to leave if they did not wish to work alongside her. Initially Foster acted not only as business manager and financier of the paper, but wrote extensively in it as well, even producing the copy on a hand press.

Foster and Fleeson

In 1849, Foster brought in a partner, RC Fleeson and the firm changed names to Foster & Fleeson. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Foster joined the Union Army, but production of the paper continued. The paper had become successful due to its independent approach to the news and its in-depth court reporting:

- "A leading feature of the Dispatch was its elaborate, accurate and interesting reports of the various courts of the county. In regard to the latter, judges and lawyers were profuse in their praise of the legal intelligence in the paper daily, and on more than one occasion lawyers, addressing juries in important cases, analyzed the testimony as it appeared in the Dispatch, and that, too, from longhand reports — there were no stenographers in those days."[3]

In 1857, the Dispatch was Pittsburgh's leading newspaper with a combined daily and weekly circulation of 14,000, compared with the number two Chronicle's 5,584.[4] Fleeson remained with the paper until his death in 1863.

Although ostensibly independent with regard to party politics, the pre-Civil War Dispatch tended in editorial sentiment toward the anti-slavery Free Soil Party and later the Know Nothings, and eventually the Republicans. The paper's warmth toward Know-Nothingism in the mid-1850s reflected Foster's belief that the movement was a better reform vehicle than the competing parties, which he saw as corrupt and beholden to the rising foreign-born vote. Foster rationalized the movement's nativism and anti-Catholicism, arguing that "the foreign Catholic vote is almost unanimously cast for slavery" and that immigrants made up much of the "rum party" opposed to temperance reforms.[5]

O'Neill and Rook

Following the Civil War, in 1865 two employees of the paper, Daniel O'Neill and Alexander W. Rook bought a half interest in the paper, eventually taking full control when Foster died in 1868. O'Neill had been city editor for several years and had his finger on the pulse of the city, and he had forged an independent path on state and national issues, lending weight to the neutrality of the newspaper's editorial page.

The paper was still four sheets, but management bought new rotary presses and they significantly enlarged its coverage, eventually doubling its size making it one of the largest and most prosperous newspapers in the United States.[6] While a risky move because of the expense, the cover price was increased from 6 to 15 cents per week and the public liked the results and circulation grew, making the Dispatch the largest circulation paper in Pittsburgh with a circulation of 14,000.

Technology upgrade

The two partners ran the paper until O'Neill's death in 1877. Following O'Neill's death, Eugene M O'Neill, Daniel's brother, took a more leading role in the paper along with Rook. E. M. O'Neill continued his brother's independent approach to political and civic issues which the public enjoyed. The same year as Daniel's death, 1877, the firm suffered the loss of the printing plant due to fire. O'Neill replaced the rotary press with a state-of-the-art "perfecting press" which could print both sides of the paper at the same time. They simultaneously reduced the size of the printed sheet and doubled the number of pages. The smaller size and greater bulk made the Dispatch stand out from the competition most of whom were using the older blanket press in a broad sheet format. Another advantage gained by introducing new technology came from the press' ability to print and fold the paper. Boys who once were used to fold in the printing plant were sent into the street to sell the paper, redoubling the publisher's marketing effort.

O'Neill led the Pittsburgh papers on the news gathering side of the operation. At this time most newspapers relied on the Associated Press newswire for their national news. Consequently, all papers were printing the same stories word for word. O'Neill reinvested the savings realized from his advanced presses and engaged correspondents in Washington and the other news centers around the country. The result was a fresher perspective and different stories from competitive papers. This advantage showed particularly in the hotly contested presidential election of 1880 which saw James A. Garfield elected.

Eugene M O'Neill years

When Rook died in 1880, Eugene M O'Neill took control of the paper and its editorial direction and eventually bought full ownership from Rook's estate.[7] E.M. continued in charge of both the editorial and business departments for the next 12 years.

The paper began publishing a Sunday edition on September 9, 1883,[8] targeting the leisure time of its audience on that day, and justifying its higher price by providing more in-depth articles and a wider selection than the daily paper. The strategy was an instant success.[9] An earlier attempt at a Sunday paper, in 1870,[10] had failed in the same year.[11]

Ownership of the paper was reorganized in corporate form under the title "The Dispatch Publishing Company" in 1888 with E.M. O'Neill as President, Bakewell Phillips, Treasurer, and C.A. Rook, Secretary. Phillips was the son of Ormby Phillips who was part owner of the paper until his death in 1884. Phillips, a former mayor of the City of Allegheny had been the business manager of the firm.[12] Eugene O'Neill continued to oversee the paper until his retirement in 1902. Alexander Rook's son, Charles A Rook, purchased control of the corporation and took over as President and editor-in-chief of the paper, Eugene O'Neill became Vice President, and Daniel O'Neill's son Florence became Treasurer.

In 1908, Charles Wakefield Cadman became the music editor and critic for the Dispatch.[13]

Paper shortage

The entry of the United States into World War I in 1917 began a period of paper shortages, especially newsprint.[14] According to The Bureau of Business Research at Northwestern University the price of newsprint doubled between 1916 and 1917.[15] Making matters worse was an increasingly difficult task of sourcing paper at all for the next five years. Matters came to a head in 1920 when a number of newspapers nationwide simply couldn't source newsprint at all and had to publish extremely truncated editions.[16] In 1921, the paper had a circulation of 56,857.[17]

In 1940, the price of newsprint doubled again, reaching a level four times higher than the pre-war price. On March 23, the paper appeared with 86 news headlines on the front page and virtually no advertising except for customers under contract. The paper shortage was not caused by a decrease in nationwide production, which had been steadily rising, instead the strong post World War I economy and the attendant advertising boom caused an increase in demand which the paper mills could not meet.[18]

Closure and liquidation

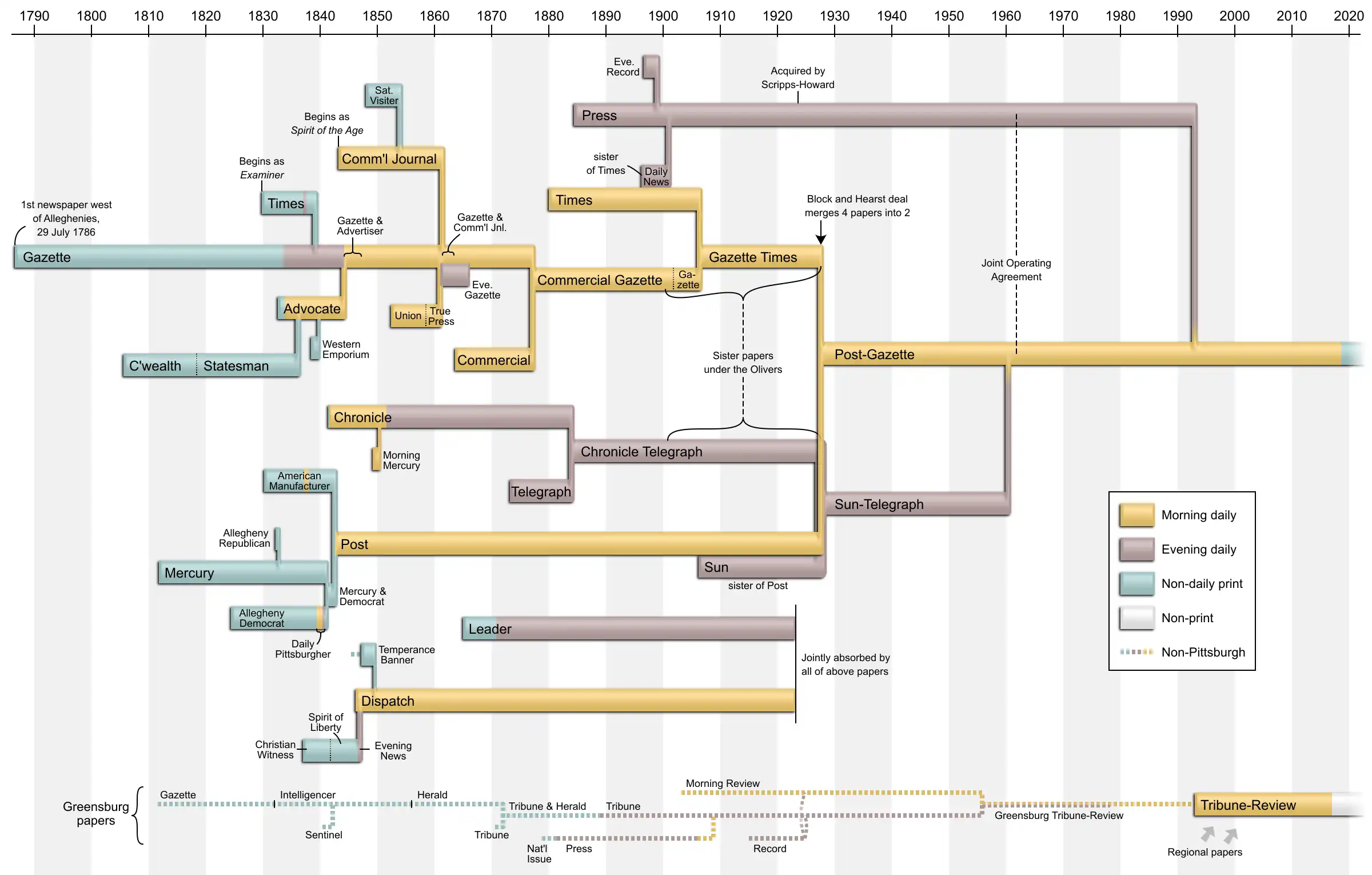

The combination of rapidly rising costs and higher spending on new press technology led to a trend toward industry consolidation in the 1910s and 1920s. Multi-city newspaper syndicates, such as Scripps-Howard, bought up independent papers and either consolidated them or closed them to cut costs. The days of a large city having 5 or 10 local papers were drawing to a close.[19]

The Pittsburgh Dispatch published its last issue on 14 February 1923, its property, plant, and goodwill having been sold to the other Pittsburgh papers: the Pittsburgh Post, The Gazette Times and the Pittsburgh Press. The circulation of the paper was merged with the other papers, and the Rook Building at 1331-1335 Fifth Avenue in Pittsburgh was sold. The paper's membership in the Associated Press was transferred to the Pittsburgh Sun. The papers taking over the Dispatch also took over the assets of the Pittsburgh Leader at around the same time.[20]

References

- ↑ "The Daily Dispatch". Pittsburgh Daily Gazette and Advertiser. Pittsburgh. 10 February 1846. p. 2, col. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Boucher, John Newton, ed. (1908). A Century and a Half of Pittsburg and Her People. Vol. 2. New York: The Lewis Publishing Company. p. 424.

- ↑ Smith, Percy (1918). Memory's Milestones: Reminiscences of a Busy Life in Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh: Murdoch-Kerr Press. p. 6.

- ↑ Thurston, George H (1857). Pittsburgh as it Is. Pittsburgh: W.S. Haven. p. 188.

foster & fleeson.

- ↑ Holt, Michael F. (1969). Forging a Majority: The Formation of the Republican Party in Pittsburgh, 1848–1860. Yale University Press. pp. 140, 164–165, 392.

- ↑ Thurston, George (1876). Pittsburgh and Allegheny in the Centennial Year. New York: AA Anderson & Son. p. 262.

- ↑ Fleming, George (1922). History of Pittsburgh and its Environs. Pittsburgh: American Historical Society. p. 340.

e.m. o'neil.

- ↑ "(untitled)". Indiana Weekly Messenger. Indiana, PA. 12 September 1883. p. 3.

- ↑ Killikelly, Sarah Hutchins (1906). The History of Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh: B.C. & Gordon Montgomery Co. p. 340. ISBN 9783849673789.

- ↑ "The Sunday Dispatch". The Pittsburgh Gazette. 16 May 1870. p. 4, col. 1.

- ↑ "Death in the Sunday Press". The Pittsburgh Leader. 1 January 1871. p. 4.

- ↑ Thurston, George Henry (1888). Allegheny County's Hundred Years. Pittsburgh: A.A. Anderson & Son. p. 302.

o'neill & rook.

- ↑ "Charles Wakefield Cadman Biography. Listen to Classical Music by Charles Wakefield Cadman". Archived from the original on 2008-09-06. Retrieved 2008-06-03.

- ↑ Tariff Information Surveys on the Articles in Paragraph 1- of the Tariff Act of 1913 and Related Articles in Other Paragraphs. Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1921. pp. 15–17.

1920 paper shortage.

- ↑ Grantham, James (1922). Wholesale Price Movements of Paper in Chicago, January 1, 1913 to June 30, 1922. Chicago: Nowthwestern University. pp. 1–13.

- ↑ "FORCED TO CONDENSE NEWS; Pittsburgh Dispatch Is Hard Hit by Print-Paper Shortage". The New York Times. 24 March 1920. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ↑ Rogers, Jason (July 1922). Newspaper Making. New York: New York Globe. p. 86.

pittsburgh dispatch circulation.

- ↑ Tariff Information Surveys on the Articles in Paragraph 1- of the Tariff Act of 1913 and Related Articles in Other Paragraphs. Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1921. pp. 15–17.

1920 paper shortage.

- ↑ "Newspaper Consolidation". The New York Times. 16 February 1923. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

- ↑ "Last Pittsburgh Dispatch". New York Times. 14 February 1923. Retrieved 2008-09-02.

External links

- Issues from 1849–1880 (intermittent coverage) from Historic Pittsburgh

- Issues from 1889–1892 available on Library of Congress' Chronicling of America Historic American Newspapers