Théodore Botrel | |

|---|---|

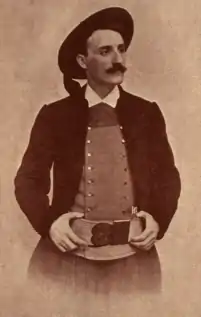

Botrel in traditional Breton costume | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Jean-Baptiste-Théodore-Marie Botrel |

| Born | 14 September 1868 Dinan, Brittany, France |

| Died | 28 July 1925 (aged 56) Pont-Aven, Brittany, France |

| Genres | chanson, melodrama |

| Occupations | Singer-songwriter, playwright, poet |

| Instruments | Vocals |

| Years active | 1895–1925 |

Jean-Baptiste-Théodore-Marie Botrel (14 September 1868 – 28 July 1925) was a French singer-songwriter, poet and playwright. He is best known for his popular songs about his native Brittany, of which the most famous is La Paimpolaise. During World War I he became France's official "Bard of the Armies".

Life

Born in Dinan, Botrel was the son of a blacksmith. He was left with his grandmother in Saint-Méen-le-Grand as a child, since his parents had moved to Paris. He joined them in the capital at the age of seven. His native language was the Gallo dialect, though almost all his songs are in standard French, and he learned the Breton language later in life.

As a teenager he became involved in amateur theatricals, performing on stage in plays, and writing songs. His first published song Le Petit Biniou (The Little Bagpipe) was not a success.

Botrel shelved his theatrical ambitions, joining the army for five years and then working as a clerk for the Paris-Lyon-Marseille railway company. He continued to appear on stage and to write and perform songs. In 1891 he met and married singer Hélène Lugton, known as Léna.

La Paimpolaise

One evening in 1895, standing in for another act, he performed his song La Paimpolaise (The Paimpol Girl) to great acclaim from the audience, launching himself as a popular singer. La Paimpolaise became his signature song – a lilting ballad about the quaint charms of the fishing village of Paimpol and its people. In fact Botrel only visited Paimpol in 1897, after he wrote the song. The song's refrain, "J'aime Paimpol et sa falaise" ("I love Paimpol and its cliff"), was apparently chosen because 'falaise' rhymes with 'Paimpolaise'. It has often been noted that there is no cliff in the town.[1] Nevertheless the nearby Pointe de Guiben has been marketed as the cliff described in the song.[2] The choice of Paimpol probably derived from the popularity of Pierre Loti's recent novel Pêcheur d'Islande, which is set in the town.[3] The song was a central feature of the repertoire of Félix Mayol until his death in 1941. Mayol also showcased many of Botrel's later songs.[3]

La Paimpolaise inspired a number of other sentimental songs which idealised Breton towns and regions. In Jésus chez les bretons (Jesus Among the Bretons) he implies that the second coming will be in Brittany.

Fame

Botrel attracted the attention of Caran d'Ache and the intellectual coterie associated with the Le Chat Noir club, though he most often performed at the rival Le Chien-Noir club. With the support of Parisian intellectuals a collection of Botrel's songs was published as Chansons de chez nous (Songs Bretonnes) in 1898, with a preface by the Breton folklorist Anatole Le Braz.[4] The book was highly praised and was awarded a prize by the Académie française.[5]

Edmond Rostand wrote, "Botrel's adorable verses make the broom-flowers sprout when one sings them".[6] François Coppée said "While I read Botrel's verses...I compare myself to a sick man dragging his walking stick along the suburb of a city and stopping now and then to listen to the young voices of the children singing. Ah, Botrel's voice is high and true and clear!."[5]

Botrel gave up his day job to become a professional singer-songwriter. When not performing in Paris, he lived in Brittany, initially taking a house in Port-Blanc, then moving permanently to Pont-Aven. He edited the journal of popular verse La Bonne Chanson and in 1905 founded the "Fête des Fleurs d'Ajonc" ("Gorse Flower Festival") in Pont-Aven, the first of the music festivals that have since become common in Brittany. In 1909, he established a permanent monument to Breton writer Auguste Brizeux in Pont-Aven.

In addition to songwriting, Botrel tried his hand at drama, writing and performing in a number of plays, including an original Sherlock Holmes story, Le Mystere de Kéravel, in which the detective solves a murder while travelling incognito in Brittany.

His wife Léna often sang duets with him, and regularly appeared in publicity images with him in traditional Breton costume (though in fact she was from Luxembourg). She also co-wrote some songs. Botrel's friend Émile Hamonic created number of photographic tableaux representing the scenes and stories of his songs and plays, which were widely sold and circulated as postcards with Botrel's signature.[3]

Botrel also became involved in the burgeoning Pan-Celticist movement. In 1904, he and Léna attended the Pan-Celtic Congress in Caernarfon as Breton representatives.[7]

Botrel was politically conservative, a Royalist and a devout Roman Catholic. Many of his later songs celebrated these values, and appealed to popular patriotism. The song Le Mouchoir rouge de Cholet (The Red Handkerchief of Cholet) is about a soldier in the Chouannerie, the Royalist Catholic rebellion against the French Revolution, who buys the handkerchief for his girl. It inspired a local manufacturer to create red Cholet handkerchiefs, the popularity of which boosted the local textile industry.[8]

World War I and after

Botrel was an enthusiastic supporter of the French cause in World War I. Turned down for service in the French army because of his age, he attempted to enlist with Belgian forces, but was again rejected. He decided to work for the war effort by writing and performing patriotic songs.

He had already published a collection of military songs before the war in 1912 as "Coups de Clairon". A British writer noted "It is a noble work, and one cannot think of another poet, here or in France, so abundantly equipped for its performance. Botrel has no counterpart in Britain, so it were vain to seek comparisons."[9]

After his rejection for military service Botrel started a monthly publication entitled Les chants du Bivouac containing songs for the soldiers. In 1915 he was appointed as official "Chansonnier des Armées", or "Bard of the Armies". According to the New York Times he was authorised by the Minister of War "to enter all military depots, camps and hospitals for the purpose of reciting and singing his patriotic poems."[4]

He travelled throughout the front line performing to the troops. The patriotic songs were also published as poems for a children's book promoting the war effort, Les Livres Rose pour la Jeunesse.[10] Botrel's most famous wartime songs were Rosalie (the nickname of the French bayonet) and Ma P'tite Mimi (about a machine-gun). The latter was revived by Pierre Desproges in the 1980s. At this time some of his lyrics were translated into English by G.E. Morrison and Edgar Preston as Songs of Brittany.

Botrel's wife Léna died in 1916. In 1918, he remarried, to Marie-Elisabeth "Maïlise" Schreiber. He had two daughters with her, the elder of whom, named Léna after his first wife, married the writer Emile Danoën. The younger, Janick, was the mother of singer Renaud Detressan.

Botrel died in 1925. His incomplete autobiography, souvenirs d'un barde errant, was published after his death. His daughter Léna later wrote extra chapters to complete the story of his life. A monument to him was erected in Paimpol designed by Pierre Lenoir. It shows the Paimpolaise gazing out to sea from the imaginary cliff.[1] There is also a statue of him in Pont-Aven.

Songwriting

Unable to write music, Botrel could only publish his work by singing the tune to a professional musician who would write it down. Initially he was denied credit for the melody of his most famous song when the transcriber Eugène Feautrier asserted that he was the "author" of the music. Another claimed credit as "arranger". Botrel was advised by specialists at the Société des auteurs, compositeurs et éditeurs de musique that "from the moment you yourself compose the melody, even if you dictate it to a musician you remain the sole author of your chanson."[11] From that point on he insisted on sole credit, but this produced some resentment from musicians who believed their contributions were being denied. It was also objected that songs and arrangements that were essentially in the style of modern Parisian chanson were being marketed as "Breton" music.[11] Botrel and Léna also made a number of recordings.

Notes

- 1 2 monument-a-theodore-botrel, Monument to Theodore Botrel], fr.topic-topos.com. Accessed 2 December 2022.

- ↑ Michelin Guide to Brittany, p. 309.

- 1 2 3 Philippe Bervas, Ce barde errant Théodore Botrel, Editions Ouest France, 2000, p. 4; passim.

- 1 2 3 "Botrel, The Trench Laureate", New York Times, 18 July 1915.

- 1 2 "Theodore Botrel: the Poet of Brittany", The Irish Monthly, 1911, vol xxxix, pp. 33–42.

- ↑ Original French: "les adorable chansons de Botrel font pousser des genêts quand on les chante".

- ↑ Marion Loffler, A Book of Mad Celts: John Wickens and the Celtic Congress of Caernarfon 1904, Gomer Press, 2000, p. 38.

- ↑ Ville de Cholet, ville-cholet.fr. Accessed 2 December 2022.

- ↑ Edgar Preston, "Theodore Botrel", T.P.'s Journal of Great Deeds of the Great War, 27 February 1915 The Military Minstrel of France – Theodore Botrel – Breton Poet, greatwardifferent.com. Accessed 2 December 2022.

- ↑ Les Livres Rose pour la Jeunesse, greatest different.com. Accessed 2 December 2022.

- 1 2 Steven Moore Whiting, Satie the Bohemian: From Cabaret to Concert Hall, Oxford University Press, 1999, p.221