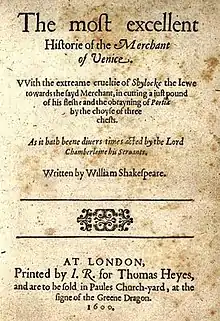

Thomas Heyes was the publisher-bookseller who published the first quarto edition of William Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice, in London, in 1600.[1] He traded from 'St Paul’s Churchyard at the sign of the Green Dragon’.[2]

The Shakespeare Connection

Thomas Heyes' right to publish Shakespeare's work is well attested. There is an entry in the Stationers' Register dated 28 October 1600:

Thomas Haies. Entred for his copie under the handes of the Wardens and by Consent of Master Robertes. A booke called the booke of the Merchant of Venyce.[3]

Based on the precise wording of this entry (“A booke called the booke…”), it has been concluded that the edition published by Heyes was an official prompt book. The book was printed by ‘I.R.’, the same James Roberts who had consented to its publication. Roberts was the printer of the playbills for Shakespeare’s theatre company, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men[4] Roberts had earlier secured the conditional rights to the play, registered by the Company of Stationers on 22 July 1598:

James Roberts. Entred for his copie vnder the handes of bothe the wardens, a booke of the Marchaunt of Venyce or otherwise called the Jewe of Venyce Prouided that yt bee not prynted by the said James Robertes or anye other whatsoeuer without lycense first had from the Right honorable the lord Chamberlen.[5]

Thomas Heyes left the copyright for this work to his son, Lawrence, in his will when the latter was only a boy. The copyright for Merchant of Venice was adjudged to ‘Lavrence Heyes’ in full court on 8 July 1619.[6] Proving this copyright was probably prompted by the publication of the False Folio edition by William Jaggard earlier that year. Lawrence published the third quarto edition of Merchant of Venice in 1637, to be sold at his shop in Fleetbridge.[7] The copyright was later transferred from Bridget Hayes and Jane Graisby to William Leake on 17 October 1657.[8] Leake published the fourth quarto edition of Merchant of Venice in 1652.

Other information

Not much more is known about Thomas or Lawrence Heyes from other sources. In 1603 Thomas petitioned King James 1, ‘for regulations to be made to carry into effect the statute ‘23 Eliz.’, for enrolment of fines and recoveries, and that he may have the office of enrolling the same’.[9] This statute was the 'Act against Reconciliation to Rome' and the fines were enormous: previously non-attendance at church earned a one shilling fine, but this Act raised the penalty to 20 pounds a month, with stiffer penalties for celebrating or attending Mass.[10]

Thomas Heyes also witnessed the will of the stationer Francis Coldock (1561–1603) in 1602. (Francis is recorded as the printer of a sermon for Thomas White in 1578). Francis' business adjoined that of Thomas Heyes; Francis' address is given as “Lombard Street, over against the Cardinals Hat; Green Dragon, St. Paul's Churchyard”.[11]

Thomas published a number of other works, including England’s Parnassus by Robert Allot (in 1600),[12] in partnership with Nicholas Ling and Cuthbert Burby. His son Lawrence appears to have published only one other work, ‘The worming of a mad dogge’, in 1617.[13]

References

- ↑ Braunmuller, A.R. (ed.) 2000. The Merchant of Venice by William Shakespeare. Penguin Classics. 103 pp. p. lii.

- ↑ Clark W.G. and Wright W.A. (eds). 1863. The Works of William Shakespeare. Vol II. MacMillan and Co, Cambridge and London. 464 pp. p. xi.

- ↑ Arber, E. (ed.). 1875–1894. Transcript of the Registers of the Company of Stationers of London, 1554-1640. 5 vols., London and Birmingham. Vol III p. 175.

- ↑ Kirschbaum L. 1955. Shakespeare and the Stationers. Ohio State University Press, Columbus, Ohio p. 204.

- ↑ Arber Vol III p. 122.

- ↑ Kirschbaum p. 235.

- ↑ Clark and Wright p. ix.

- ↑ Eyre, G. E. B. and G. R. Rivington (eds.) 1913–1914. A Transcript of the Registers of the Worshipful Company of Stationers from 1640–1708. 3 vols, London. Vol II p 150.

- ↑ Green, M.A.E. (ed.) 1857. Calendar of State Papers Domestic: James I, 1603-1610. p. 61.

- ↑ Tanner, J.R. 1922. Tudor Constitutional Documents AD 1485–1603 with an historical commentary. Cambridge University Press, 636 pp. p 154.

- ↑ Plomer, H.R. 1903. Abstracts from the wills of English printers and stationers from 1492 to 1630. Bibliographical Society. 68 pp.; p. 37.

- ↑ Kirschbaum p. 346.

- ↑ Kirschbaum p. 235.