Thomas J. Jarvis | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from North Carolina | |

| In office April 19, 1894 – January 23, 1895 | |

| Appointed by | Elias Carr |

| Preceded by | Zebulon Baird Vance |

| Succeeded by | Jeter C. Pritchard |

| 16th United States Minister to Brazil | |

| In office July 11, 1885 – November 19, 1888 | |

| President | Grover Cleveland |

| Preceded by | Thomas A. Osborn |

| Succeeded by | Robert Adams, Jr. |

| 44th Governor of North Carolina | |

| In office February 5, 1879 – January 21, 1885 | |

| Lieutenant | James L. Robinson |

| Preceded by | Zebulon Baird Vance |

| Succeeded by | Alfred Moore Scales |

| 3rd Lieutenant Governor of North Carolina | |

| In office January 1, 1877 – February 5, 1879 | |

| Governor | Zebulon Baird Vance |

| Preceded by | Curtis H. Brogden |

| Succeeded by | James L. Robinson |

| Speaker of the North Carolina House of Representatives | |

| In office November 21, 1870 – November 18, 1872 | |

| Preceded by | W. A. Moore |

| Succeeded by | James L. Robinson |

| Member of the North Carolina House of Representatives for Tyrrell | |

| In office November 16, 1868 – November 18, 1872 | |

| Preceded by | N. W. Walker (as Member, House of Commons) |

| Succeeded by | B. Jones |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 18, 1836 Jarvisburg, North Carolina |

| Died | June 17, 1915 (aged 79) Greenville, North Carolina |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Alma mater | Randoph-Macon College |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Confederate States Army |

| Years of service | 1861–1864 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Unit | Eighth North Carolina Regiment |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

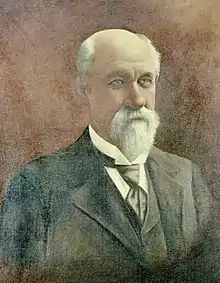

Thomas Jordan Jarvis (January 18, 1836 – June 17, 1915) was the 44th governor of the U.S. state of North Carolina from 1879 to 1885. Jarvis later served as a U.S. Senator from 1894 to 1895, and helped establish East Carolina Teachers Training School, now known as East Carolina University, in 1907.

Biography

Early years

Born in Jarvisburg, North Carolina, in Currituck County, he was the son of Elizabeth Daley and Bannister Hardy Jarvis, a Methodist minister and farmer[1] and brother of George, Ann, Margaret, and Elizabeth. His family was of English descent and some of its members highlighted at various points in the history of North Carolina. So, Thomas Jarvis was lieutenant governor of Albemarle during the government of Philip Ludwell, between 1691–97, and Samuel Jarvis led the militia of Albemarle during his fight in the Revolutionary War. Raised in a poor family, although he had the necessities of life, Jarvis worked when he was young in three hundred acre farm owned by his father, while he was studying about the common schools.[1] Jarvis was educated locally and at nineteen went on to attend Randoph-Macon College, earning an M.A. in 1861. He had to exercise as teacher during the summer to pay for college tuition.[1] An educator by training, Jarvis opened a school in Pasquotank County and would later be one of the founders of East Carolina University.

Career

Jarvis enlisted in the military at the beginning of the American Civil War and served in the Eighth North Carolina Regiment. On April 22, 1863 he was named Captain.[1] Captured and exchanged in 1862, Jarvis, was injured and permanently disabled at the Battle of Drewry's Bluff in 1864. After the war ended, he was on sick leave in Norfolk and in May 1865, he got probation, returning to Jarvisburg.

In 1865, Jarvis returned home and opened a general store before being named a delegate to the 1865 state constitutional convention. In 1867 Jarvis bought entrepreneur William H. Happer's share of their small general store. After getting a license to practice law in June of that year, he abandoned the store and moved to Columbia.[1]

Active in the Democratic Party, Jarvis was elected to the State House in 1868 and served there for four years, two of them (1870–1872) as Speaker of the House. In 1872, he was a Democratic elector-at-large on the Horace Greeley ticket. Jarvis also married Mary Woodson in December 1874.

An opponent of federal Reconstruction policy, Jarvis was elected the third lieutenant governor in 1876 on a ticket with Zebulon Vance. In 1879, Vance resigned the governorship to serve in the United States Senate, and Jarvis filled the vacant position. As governor, he fought against government corruption and attempted to cut taxes, the state's debt, and government control. He also completed the sale of various state railways to private companies. He established mental health services in Morganton and Goldsboro, managed the establishment of normal schools for teachers in North Carolina and helped develop the State Board of Health.[1]

He won election in his own right in 1880, defeating Daniel G. Fowle for the Democratic nomination and narrowly winning over Republican challenger Ralph Buxton. In office, Jarvis convinced the legislature to authorize construction of the North Carolina Executive Mansion, although it was not completed until 1891.[2][3] He "supported establishing a system of county superintendents of education elected by boards of education, grades of teacher certification, standards of examinations for public school teachers, and lists of recommended textbooks. Also, Funds for the mental institutions continued to increase, and the laws of North Carolina were for the first time codified and state insurance laws fully defined. Also, was built a governor's mansion".[1]

Term limited, Jarvis stepped down as governor in 1885, but was appointed United States Minister to Brazil by President Grover Cleveland. Jarvis held this post for four years, after which he practiced law in Greenville, North Carolina. Following Senator Vance's death in 1894, Jarvis again succeeded him in office, serving as a U.S. Senator through an appointment by Gov. Elias Carr. In 1895, the state legislature, now under the control of Republicans and Populists, would not elect Jarvis to a term of his own.

In 1896, Jarvis was a delegate to the Democratic National Convention, where he supported William Jennings Bryan in his last major political act. He was instrumental in the founding of what is now East Carolina University in Greenville, where the oldest residential hall on campus is named in his memory.

In 1898, while not directly involved, Jarvis's political rhetoric may have contributed to the Wilmington insurrection of 1898, a violent coup d'état by a group of white supremacists. They expelled opposition black and white political leaders from the city, destroyed the property and businesses of black citizens built up since the Civil War, including the only black newspaper in the city, and killed an estimated 60 to more than 300 people.[4][5]

Jarvis reopened his law firm and in 1912, he founded a partnership with Frank Wooten.[1] In November of 1914, Jarvis presided over the unveiling of the Pitt County Confederate Soldiers' Monument.[6]

He died at his home in Greenville on June 17, 1915.[7]

Legacy

- In addition to the ECU residence hall, a local United Methodist church[8] and a street in Greenville are named in his memory.

- At one time, several personal artifacts were on display at the church.

Personal life

Jarvis married Mary Woodson in December 1874.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Thomas Jordan Jarvis, 1836–1915". Archived from the original on February 3, 2018. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) Retrieved on April 28, 2022. - ↑ "News & Observer: Executive Mansion gets its place in history". Archived from the original on April 1, 2012. Retrieved May 13, 2010. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 1, 2012. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ↑ "North Carolina Historical Marker". Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- ↑ "Race Question in Politics: North Carolina White Men Seek to Wrest Control from the Negroes". The New York Times. Raleigh, North Carolina. October 24, 1898. p. 1. Retrieved April 8, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Thomas Jordan Jarvis and the White Supremacy Campaign of 1898". collectio.ecu.edu. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ↑ Mullis, Justin (May 4, 2022). ""Unveiling Meaning: the Pitt County Confederate Soldiers' Monument and Lost Cause Sentiment"" (PDF). The ScholarShip: 20. Retrieved December 14, 2022.

- ↑ "Ex-Governor Jarvis Dies at Greenville". The Charlotte Observer. Greenville, North Carolina. June 18, 1915. p. 1. Retrieved April 28, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Jarvis Memorial UMC - Home". www.jarvis.church. Retrieved November 26, 2022.