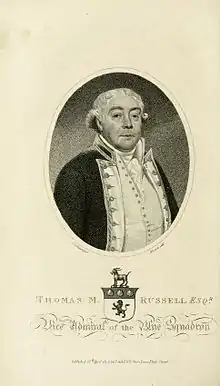

Thomas McNamara Russell | |

|---|---|

| |

| Died | 22 July 1824 near Poole, Dorset |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Rank | Vice-Admiral |

| Commands held | HMS Diligent HMS Bedford HMS Hussar HMS Diana HMS Vengeance HMS Princess Royal Second in command, Channel Squadron North Sea Fleet |

| Battles/wars | |

| Relations | Sir John Macnamara Hayes |

Thomas McNamara Russell (died 22 July 1824) was an admiral in the Royal Navy. Russell's naval career spanned the American Revolutionary War, French Revolutionary War and Napoleonic War.

Admiral Russell is best remembered for his command of a squadron in the North Sea when he took possession of Heligoland after Denmark came into the war on the side of the French in 1809. His career was also notable due to the single-ship action fought between the 20-gun HMS Hussar and the 32-gun French frigate Sybille in which he captured the French frigate despite her superior number of men and guns. There is controversy surrounding the event in that the capture happened towards the end of the American Revolution and the British officers claimed that the French were flying false colours and a distress flag during the action. Whilst it was common for ships of opposing nations to lure, or escape from, one another with false colours[1] it was considered dishonourable to continue flying false flags once the action had begun. Similarly, the flying of a flag of distress was not an acceptable ruse de guerre, as it would dissuade shipping from approaching a vessel in genuine distress.

Early life and career

Russell was the son of an Englishman who settled in Ireland, where he married a Miss Macnamara, probably a daughter and coheiress of Sheedy MacNamara of Balyally, County Clare. On the death of his father when he was five years old, he is said to have inherited a large fortune, which, by the carelessness or dishonesty of his trustees, disappeared before he was fourteen.[2]

After a short period in the Merchant Navy[3] Russell first appears on the ship's muster of HMS Cornwall guardship at Plymouth in 1766. He was moved as an able seaman to the 74-gun third-rate Arrogant. He served as an able seaman for three years until his promotion to midshipman in 1769 aboard the cutter Hunter employed on "preventive service" in the North Sea.[3] Russell was promoted master's mate aboard HMS Terrible, guardship at Portsmouth under Captain Mariot Arbuthnot.[3]

American Revolutionary War

He passed his examination on 2 December 1772, being then described in his certificate as "more than 32."[3] In 1776 he was serving on the coast of North America, and on 2 June was promoted by Rear-Admiral Molyneux Shuldham to be lieutenant of the sloop Albany, from which he was moved to his first command, the 12-gun brig HMS Diligent.[4] During a cruise off Chesapeake Bay, Russell engaged and fought the 16-gun privateer Lady Washington. She was captured and sold for £26,000, of which, as captain, Russell was entitled to two-eighths in prize money.[4] Russell cruised the American coastline and was successful, capturing eight prizes in round five weeks.[5] On his return to England he was appointed to the Raleigh, under Captain James Gambier, afterwards Lord Gambier, and was present at the relief of Jersey in May 1779,.[6] Briefly Russell was placed in command of Drake's Island lying in Plymouth Sound as a reward for his services on Jersey.[5] Russell was reassigned to the Raleigh when she formed part of the fleet that accompanied Vice-Admiral Arbuthnot's and Sir Henry Clinton's expedition and Russell was with the Raleigh at the Siege of Charleston. The siege and capture of Charlestown saw the biggest surrender of men of the Continental Army of the entire war.[7] At Charlestown Russell was promoted by Arbuthnot on 11 May 1780 to the command of sloop HMS Beaumont, from which, on 7 May 1781, he was promoted post-captain and put in command of the third-rate HMS Bedford.[8] Apparently this was for rank only,[3] and he was almost immediately appointed to HMS Hussar of 20 guns. Hussar had been the 28-gun Protector of the Massachusetts State Navy but was captured by the British and refitted with just 20-guns, classifying her as a sixth-rate post ship, the smallest class of vessel that a post captain could command. Russell cruised in her along the coast of North America with marked success, taking several prizes.[3]

Capture of the Sibylle

On 22 January 1783 Hussar sighted the French 32-gun frigate Sybille. The Sybille, commanded by Monsieur le Comte de Kergariou-Locmaria. The French ship had been engaged three weeks previously with the 32-gun British frigate HMS Magicienne under Captain Thomas Graves. Both ships had fought until they had both been dismasted and were forced to disengage. Sybille made for a French port under a jury rig and was then caught in a violent storm. Due to this unfortunate series of events, Kregarou had been obliged to throw twelve of his guns overboard. When she sighted the Hussar, Kregarou ordered the British flag hoisted over the French, the recognised signal of a prize, and at the same time, in the shrouds, another British flag, union downwards, the internationally recognised signal of distress. Accordingly, Russell, bore down to her assistance, but as the two ships drew near, Russell became suspicious and bore away. Seeing this, Kregarou fired his broadside, causing some damage but not as much as he could have done had Russell not turned away. Kregarou then attempted to board and overwhelm the Hussar whilst still flying false colours and the distress flag. The Hussar's crew managed to repel the boarding party. The battle continued, with both sides taking damage until a large ship came in sight. She proved to be the 74-gun HMS Centurion, and the 16-gun sloop HMS Terrier also appeared over the horizon. At the approach of two further enemies, Sybille surrendered. The rules of war that were accepted at the time were that a ship might fly a country's flag other than its own in order to escape or lure an enemy but that before the engagement commenced they must remove the decoy flag and replace it with that of their own. Alongside this, ships were expected to only fly a distress flag if they were actually in distress. Luring enemies into a trap using a distress flag was an unacceptable ruse de guerre. The French captain had therefore broken two of the fundamental rules of sea warfare.[9] Kergarou came aboard the Hussar to surrender his sword. the Count handed Russell his sword and complemented the Captain and his crew on the capture of his vessel. Russell took the sword and reportedly said:

"Sir, I must humbly beg leave to decline any compliments to this ship, her officers, or company, as I cannot return them. She is indeed no more than a British ship of her class should be. She had not fair play; but Almighty God has saved her from the most foul snare of the most perfidious enemy. - Had you, Sir, fought me fairly, I should, if I know my own heart, receive your sword with a tear of sympathy. From you, Sir, I receive it with inexpressible contempt. And now, Sir, you will please observe, that lest this sword should ever defile the hand of any honest French or English officer, I here, in the most formal and public manner, break it."[10]

Russell stuck the blade into the deck and broke the blade in half and threw it to the deck. He placed the Count under close arrest. The crew of the Hussar discovered £500 in valuables aboard the Sybille, which the French officers claimed as theirs and Russell permitted them to keep even though it would have reduced his and his crew's prize money.[11]

When Russell brought the prize into New York City he reported the circumstance, and his officers swore an affidavit in support of their captain. The Treaty of Paris was then on the point of being concluded, and in consequence the Admiralty Board and British government thought the affair would cause undue scandal and kept the official account from the general public and did not publish Russell's letter. Kergariou sent his subordinate, the Chevalier d'Ecures to see Russell. He threatened that when he should be released, he would, through influence at the French Court, acquire another ship and would obtain the requisite orders he needed to hunt down and capture Russell in retaliation if Russell reported the incident. When Russell failed to be moved, the Count, again through his subordinate issued a challenge to Russell to demand personal satisfaction. Russell considered the challenge and returned with the answer to the Chevalier: "Sir I have considered your challenge maturely...I will fight him, by land or by water, on foot or on horseback, in any part of this globe that he pleases. You will, I suppose, be his second; and I shall be attended by a friend worthy of your sword."[12]

On the declaration of peace, Hussar returned to England for decommissioning, and Russell was offered a knighthood, which he refused, as his income would not have been enough to support the title.[13] Russell was informed that Kregarou had been tried and acquitted of the loss of his ship and the breach of internationally recognised laws and applied to the Admiralty for permission to travel to France. Admiral Arbuthnot accompanied him as his second. Kregarou wrote to Russell and expressed his gratitude of the treatment that he and his crew had received from Russell after they had been captured and informing Russell that he intended to move to the Pyrenees. Arbuthnot convinced Russell that he should not follow the Count but return to England. Russell returned to England and remained unemployed until 1791.

Command in the West Indies

In 1791 Russell was appointed to the 32-gun fifth-rate frigate Diana on the West Indian station. During his time on the station, Russell made an impact, first with the inhabitants of Jamaica who highly praised his conduct[14] and secondly with the Spanish Governor in Havana, Cuba, Luis de Las Casas. When Russell refused to have a Spanish guard put aboard the Diana when she was docked in Havana, de Las Casas said "If this McNamara Russell were any thing but the Captain of a British Frigate, violating and opposing the orders of my Sovereign, I never knew a man who I would sooner call my friend.".[15]

Rescue of Lieutenant Perkins

At the end of 1791 the slaves of the French colony on Santo Domingo had risen in revolt and Admiral Philip Affleck sent Russell and the Diana with a convoy of supplies to the French authorities. At a dinner held in his honour, he learned that a British officer, Lieutenant John Perkins, was imprisoned at Jérémie, on a charge of having supplied the revolting army with arms. Officially Britain and France were not at war and Russell requested that Perkins be released. The French authorities promised that he would be and then later refused. After numerous letters had been exchanged Russell determined that the French did not intend to release Perkins. Russell sailed around Cap-Français to Jérémie and met with the 12-gun HMS Ferret under Captain Nowell. They agreed that Nowell's first lieutenant, an officer named Godby, would go ashore and recover Perkins whilst the two ships remained offshore within cannon shot, ready to land an invasion force if need be.[16] Lieutenant Godby landed and through negotiations secured Perkins's release.[17]

French Revolutionary Wars

Russell returned to England in 1792, and in 1796 was appointed to the third-rate, 74-gun Vengeance,[6] again for service in the West Indies, where, under Rear-admiral Henry Harvey, he took part in the reduction of Saint Lucia and Trinidad under Harvey and Sir Ralph Abercromby. The Vengeance returned to England in the spring of 1799, and formed part of the Channel fleet under Admiral Jervis during the summer, after which she was paid off, and in the following April Russell was appointed to the 98-gun second-rate Princess Royal, which he commanded till his promotion to the rank of rear admiral on 1 January 1801.[18] On the renewal of the war with France in 1803 he hoisted his flag on board the Dictator. He was placed in command of a division under the orders of Lord Keith in the North Sea Fleet stationed in the Downs.

Napoleonic Wars

Russell was promoted to Rear-Admiral of the Red on 21 April 1804.[19] He then raised his flag on Monmouth. On 9 November 1805 he was promoted to be vice-admiral,[20] and in 1807 was appointed Commander-in-Chief, North Sea.[21] In September, on the news of war having been declared by Denmark, he took possession of Heligoland, which during the war continued to be the great depôt of the UK trade with Germany. He was promoted from Vice Admiral of the Red to Admiral of the Blue on 12 August 1812.[22]

Family and death

He married Miss Phillips in about 1793. His wife died in 1818.[3] He had one daughter and heir, Lucinda Russell born 18 April 1789, presumably from a previous marriage, who married Captain George Patey.[23] Admiral Russell died suddenly, in his carriage, near Poole, Dorset on 22 July 1824.[3]

References

- ↑ Cordingly, David (2007). Cochrane The Dauntless: The Life and Adventures of Thomas Cochrane. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7475-8545-9.

- ↑ The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 17. Bunney & Gold. p. 441.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 49. Smith, Elder & Co.

- 1 2 The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 17. Bunney & Gold. p. 442.

- 1 2 The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 17. Bunney & Gold. p. 443.

- 1 2 Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 59. Smith, Elder & Co.

- ↑ Carl P. Borick (2003). A gallant defense: the Siege of Charleston, 1780. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 9781570034879.

- ↑ Isaac Schomberg (2003). Naval chronology; or, An historical summary of naval & maritime events, from the time of the Romans, to the Treaty of Peace, 1802. C, Rowarth, Bell Lane, Fleet Street. p. 353.

- ↑ de Vattel, Emerich (1797). The Law of Nations or the Principles of Natural Law. London: G.G and J. Robinson. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- ↑ The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 17. Bunney & Gold. p. 449.

- ↑ The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 17. Bunney & Gold. pp. 445–450.

- ↑ The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 17. Bunney & Gold. p. 450.

- ↑ The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 17. Bunney & Gold. p. 452.

- ↑ The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 17. Bunney & Gold. pp. 453–455.

- ↑ The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 17. Bunney & Gold. pp. 455–456.

- ↑ The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 27. Bunney & Gold. pp. 351–352.

- ↑ The Naval Chronicle. Vol. 17. Bunney & Gold. pp. 458–462.

- ↑ "No. 15324". The London Gazette. 30 December 1800. p. 10.

- ↑ "No. 15695". The London Gazette. 21 April 1804. p. 496.

- ↑ "No. 15859". The London Gazette. 5 November 180. p. 1374.

- ↑ Marshall, John (18 November 2010). Royal Naval Biography: Or, Memoirs of the Services of All the Flag-Officers, Superannuated Rear-Admirals, Retired-Captains, Post-Captains, and Commanders. Cambridge University Press. p. 145. ISBN 9781108022644.

- ↑ "No. 16632". The London Gazette. 11 August 1812. p. 1584.

- ↑ "Register Report for George Patey" (PDF). 22 July 2008. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- Attribution

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Russell, Thomas Macnamara". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Russell, Thomas Macnamara". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.