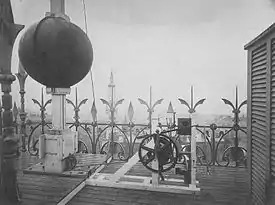

A time ball or timeball is a time-signalling device. It consists of a large, painted wooden or metal ball that is dropped at a predetermined time, principally to enable navigators aboard ships offshore to verify the setting of their marine chronometers. Accurate timekeeping is essential to the determination of longitude at sea.

Although time balls have since been replaced by electronic time signals, some time balls have remained operational as historical tourist attractions.

History

The fall of a little ball was in antiquity a way to show to people the time. Ancient Greek clocks had this system in the main square of a city, as in the city of Gaza in the post-Alexander era, and as described by Procopius in his book on Edifices. Time ball stations set their clocks according to transit observations of the positions of the sun and stars. Originally they either had to be stationed at the observatory, or had to keep a very accurate clock at the station which was set manually to observatory time. Following the introduction of the electric telegraph around 1850, time balls could be located at a distance from their source of mean time and operated remotely.

The first modern time ball was erected at Portsmouth, England, in 1829 by its inventor Robert Wauchope, a captain in the Royal Navy.[1] Others followed in the major ports of the United Kingdom (including Liverpool) and around the maritime world.[1] One was installed in 1833 at the Greenwich Observatory in London by the Astronomer Royal, John Pond, originally to enable tall ships in the Thames to set their marine chronometers,[2] and the time ball has dropped at 1 p.m. every day since then.[3] Wauchope submitted his scheme to American and French ambassadors when they visited England.[1] The United States Naval Observatory was established in Washington, D.C., and the first American time ball went into service in 1845.[1]

Time balls were usually dropped at 1 p.m. (although in the United States they were dropped at noon). They were raised half way about 5 minutes earlier to alert the ships, then with 2–3 minutes to go they were raised the whole way. The time was recorded when the ball began descending, not when it reached the bottom.[3] With the commencement of radio time signals (in Britain from 1924), time balls gradually became obsolete and many were demolished in the 1920s.[4]

A contemporary version of the concept has been used since 31 December 1907 at New York City's Times Square as part of its New Year's Eve celebrations; at 11:59 p.m., a lit ball is lowered down a pole on the roof of One Times Square over the course of the sixty seconds ending at midnight. The spectacle was inspired by an organizer having seen the time ball on the Western Union Building in operation.[5][6]

Around the world

Over sixty time balls remain standing, though many are no longer operational. Existing time balls include:

Australia

- The Old Windmill, Brisbane, Queensland

- Fremantle, Western Australia

- Sydney Observatory, New South Wales

- Newcastle Customs House, New South Wales

- Semaphore, South Australia

- Williamstown Lighthouse, Victoria

- Geelong Telegraph Station, Victoria

Canada

- Citadelle of Quebec, Quebec City no longer true.

Clearly seen from the river and aligned on the meridian for observation purposes, Building 20, also known as the Ball House, is the former observatory and time ball tower.

New Zealand

In March 1864 New Zealand's first time ball was established at Wellington. This was followed by Port Chalmers in June 1867, Wanganui in October 1874, Lyttelton in December 1876 and Timaru in 1888. Attempts were made by some people in Auckland to establish time balls there from 1864 onwards, but these were not recognized by the authorities until a permanent time ball was mounted on the Ferry Building in August 1901.

- Port Chalmers

- Established by the Otago Provincial Council on top of Observation Point in Port Chalmers in June 1867 the time ball service initially operated at 1 pm on all days of the week except Sundays. The service was discontinued in October 1877, but following concerns raised by 11 shipmasters the service resumed in April 1882 as a weekly service. In 1910 the time keeping service was discontinued but the ball however continued to be used until 1931 as a warning device. It was removed in 1970 but a replacement was restored to service in 2020.[8]

- Lyttelton

- Established in December 1876 the Lyttelton Timeball Station in Lyttelton, New Zealand, was operational until it was damaged in the 2010 Canterbury earthquake. Further severe damage occurred in the February 2011 Christchurch earthquake,[9] and a decision was made in March 2011 to dismantle the building, a danger to the public,[10] but the tower collapsed during the major aftershock that hit the Lyttelton area on 13 June 2011.[11] In November 2012, a large financial donation [12] was made available to contribute towards rebuilding the tower, a project the community considered. On 25 May 2013, it was announced that the tower and ball would be restored, and that funds were to be sought from the community to rebuild the rest of the station. The station was officially reopened on 2 November 2018.[13][14]

- Wellington

- The Wellington time ball service started in March 1864.[8] It received its time information from the Dominion Observatory which was also communicated to the Lyttelton time ball service.[15] Dunedin used local observatory facilities.[8]

- Wellington had two time ball sites – the time ball was erected at the first site by mid-January 1864 on top of the Custom House building on the Wellington waterfront [16] and later relocated in 1888 to the J Shed Woolstore on top of the accumulator tower.[8] This building and the time ball burnt down on 9 March 1909.[17]

- Instead of replacing the Wellington time ball after the second site burnt down, time light signals were introduced at the Dominion Observatory. The earliest record of this was 22 February 1912.[18] They were in use until 1937 when wireless signals took over as the new way to keep time.[15]

Poland

South Africa

Spain

- The Real Instituto y Observatorio de la Armada in San Fernando, Cádiz continues to activate its time ball every day at 13:00 (ROA Time). After better timekeeping at sea made it obsolete, it was disabled, but it was reactivated in the late 20th century.[19]

- The Royal House of the Post Office in Puerta del Sol, Madrid, operated a time ball for Madrid. Nowadays it is only used to mark the imminent start of the bell strikes that mark the New Year at midnight. The main Spanish TV networks broadcast the event, allowing spectators to eat the traditional Twelve Grapes.

United Kingdom

- Timeball Tower, Deal, Kent, England. Operates hourly and has recently been refurbished.

- Margate Clock Tower, Kent, England

- Royal Observatory, Greenwich, England

- Time Ball Buildings, Leeds, England

- Guildhall, Kingston upon Hull, England. The only maritime timepiece on a municipal building. It dates back to 1918 and is the highest in the UK.[20]

- Clock Tower, Brighton, East Sussex, England. (originally operated hourly, but was later stopped as it was too noisy)[21]

- Nelson's Monument on Calton Hill, Edinburgh, Scotland

- Flat Iron Building in Prescot, Merseyside. Added during restoration of the building, the timeball dates from the 1800s but is controlled by a newly-built mechanism.[22]

United States

Gallery

.jpg.webp)

Deal Timeball, Deal, UK

Deal Timeball, Deal, UK Gdańsk, Poland

Gdańsk, Poland Gothenburg, Sweden

Gothenburg, Sweden

Royal House of the Post Office, Madrid, Spain

Royal House of the Post Office, Madrid, Spain Clock tower, Margate, Kent, UK

Clock tower, Margate, Kent, UK Clock tower, Brighton, UK

Clock tower, Brighton, UK Time ball, Cape Town, South Africa

Time ball, Cape Town, South Africa Time ball, Williamstown Lighthouse, Victoria, Australia

Time ball, Williamstown Lighthouse, Victoria, Australia

See also

- Blackhead Point, in Hong Kong, where a time ball was operated from 1908 to 1933

- History of longitude

- Shepherd Gate Clock

- Time signal

- Weather ball

- Greenwich Mean Time (GMT)

- Times Square Ball

- List of objects dropped on New Year's Eve

References

- 1 2 3 4 Aubin, David (2010). The Heavens on Earth: Observatories and Astronomy in Nineteenth-Century Science and Culture. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-8223-4640-1.

- ↑ "Greenwich Time Ball". Royal Museums Greenwich.

- 1 2 "Time ball". Greenwich2000. Greenwich Mean Time. 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- 1 2 "The Gdańsk Nowy Port Lighthouse and Time Ball". Archived from the original on 13 February 2012. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- ↑ McFadden, Robert D. (31 December 1987). "'88 Countdown: 3, 2, 1, Leap Second, 0". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ↑ "NYC ball drop goes 'green' on 100th anniversary". CNN. 31 December 2007. Retrieved 31 December 2007.

- ↑ "Lyttelton Timeball Station, Christchurch". Yahoo! Travel. Archived from the original on 10 March 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 Kinns, Roger (2017). "The Principal Time Balls of New Zealand". Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage. 20 (1): 69–94. Bibcode:2017JAHH...20...69K. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1440-2807.2017.01.05. S2CID 209901718.

- ↑ "New Zealand quake: The epicentre town". BBC News. 25 February 2011.

- ↑ Gates, Charlie (4 March 2010). "Timeball Station to be demolished". stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- ↑ Greenhill, Marc (14 June 2011). "Workmen unscathed as Timeball Station collapses". stuff.co.nz. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- ↑ Greenhill, Marc (28 November 2012). "Donor fronts to save Lyttelton Timeball Station". Stuff. stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ↑ Lee, Francesca (25 May 2013). "Million dollar donation to rebuild Lyttelton Timeball". Stuff. stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ↑ "$1m donation to rebuild timeball". Radio New Zealand. radionz.co.nz. 25 May 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- 1 2 Kinns, Roger (2017). "The Time Light Signals of New Zealand: Yet Another Way of Communicating Time in the Pre-Wireless Area". Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage. 20 (2): 211–222. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1440-2807.2017.02.06. S2CID 217198680.

- ↑ "Wellington (from our own correspondent)". Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle. 11 January 1864. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ↑ "A Big Blaze". The Dominion. 10 March 1909. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ↑ "Ships and Shipping". New Zealand Times. 22 February 1912. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ↑ Atienza, Antonio (30 June 2018). "La bajada de la bola del Observatorio se escucha por martinete". Andalucía Información (in Spanish). Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ↑ "Hull Guildhall's Time Ball set to rise and fall once again". BBC News. BBC. Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

The ball is one of just a few nationally and is the only maritime timepiece on a municipal building. It dates back to 1918 and is the highest in the UK.

- ↑ "Heritage Gateway Listed Buildings Online — Clock Tower and Attached Railings, North Street (north side), Brighton, Brighton and Hove, East Sussex". Heritage Gateway website. Heritage Gateway (English Heritage, Institute of Historic Building Conservation and ALGAO:England). 2006. Retrieved 2 June 2010.

- ↑ Rugg, Aaliyah (18 June 2023). "Building 'people from across the world will visit' after revamp". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 20 June 2023.

- ↑ 1913: Titanic Memorial Lighthouse Commemorates Victims of Ocean Tragedy", Newsday, August 24, 2005. Accessed December 21, 2023, via Newspapers.com. "From 1913 until 1967 a black 'time ball' at the top activated by a telegraphic signal from the National Observatory in Washington DC dropped at noon every day signaling the time to ships in the harbor."

External links

- "List of Timeballs". Index to the House Documents, Otherwise Publ. as Executive Documents. U.S. Congress. 1876–1877. pp. 305–308. List of time balls worldwide in 1876.

- Time ball/cannon hobbyist

- Time ball and cannon Association