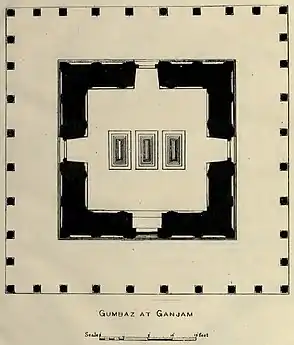

Gumbaz | |

| 12°24′36″N 76°42′50″E / 12.4100°N 76.7139°E | |

| Location | Srirangapatna, India |

|---|---|

| Type | Mausoleum (Persian) |

| Material | Black Granite and Amphibolite |

| Height | 20 metres (66 ft) |

| Beginning date | 1782 |

| Completion date | 1784 |

| Dedicated to | Hyder Ali, Tippu Sultan and family |

| Variant Names Tippu Samadhi | |

The Gumbaz at Srirangapattana is a Muslim mausoleum at the centre of a landscaped garden, holding the graves of Tippu Sultan (Western Side), his father Hyder Ali (Middle) and his mother Fakhr-Un-Nisa (Eastern Side). It was built by Tippu Sultan to house the graves of his parents. The British allowed Tippu to be buried here after his martyrdom in the Siege of Srirangapatna in 1799.[1][2]

History

The Gumbaz was raised by Tipu Sultan in 1782-84 at Srirangapattana to serve as a mausoleum for his father and mother.[3] The mausoleum was surrounded by a cypress garden which is said to have different species of flowering trees and plants collected by Tippu Sultan from Persia, Ottoman Turkey, Kabul and French Mauritius.[4]

The original carved doors of the mausoleum have been removed and are now displayed at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. The present doors made of ebony and decorated with ivory were gifted by Lord Dalhousie[5][6][7]

Architecture

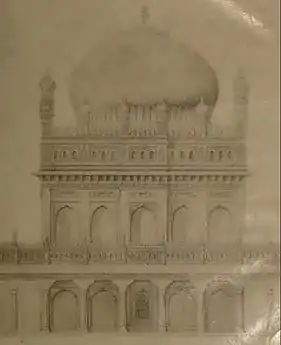

Gumbaz, Seringapatam

Gumbaz, Seringapatam

The Gumbaz is designed in the Persian style, with a large rectangle shaped garden, having a path leading to the mausoleum. In the middle of the garden, the Gumbaz stands on an elevated platform. The dome is supported by sharply cut black granite pillars. The doors and windows have latticework cut through in stone on the same black granite material. The walls inside are painted with tiger stripes, the colours of Tippu Sultan. The three graves of Tippu Sultan, his father Hyder Ali and his mother Fakr-Un-Nisa are located inside the mausoleum. Many of Tippu's relatives are buried outside the mausoleum in the garden. Most of the grave inscriptions are in Persian. Next to the Gumbaz is the Masjid-E-Aksa, which was also built by Tippu Sultan[1][9][10]

The Gumbaz uses the Bijapur style of construction, and consists of a dome placed on a cubical structure, with ornamental railings and turrets decorated with finals which are spherical shaped. The dome is supported by 36 black granite pillars, and has an east facing entrance.[11]

Burials

Gumbaz entrance, Seringapatam

Gumbaz entrance, Seringapatam_-_Copy.jpg.webp) Mausoleum of Hyder Ali and Tipoo Sultan (1858)[12]

Mausoleum of Hyder Ali and Tipoo Sultan (1858)[12]

Inside the mausoleum, the middle grave is that of Hyder Ali, to his east is Tipu Sultan's mother, and to his West Tipu Sultan is buried. On the southern side of the veranda outside are the graves of Sultan Begum - Tipu's sister, Fatima Begum - Tipu's daughter, Shazadi Begum - infant daughter, Syed Shahbaz - Tipu's son-in-law, Mir Mahmood Ali Khan, and his father and mother. On the East side is the black grave supposedly of Tipu's foster mother Madina Begum. There is an elevation on the veranda with 3 rows of graves, with the first having no headstones. Another row has 14 graves - 8 women and 6 men, including that of Malika Sultan e Shaheed or Ruqia Banu, Burhanuddin Shaheed - brother-in-law of Tipu and brother of Ruqia Banu, Nizamuddin and 1 unmarked grave. The third row consists of 14 graves, 9 women and 5 men and includes Nawab Muhammad Raza Ali Khan or Ban Ki Nawab who was killed in the Battle for Coorg, and an unidentified grave. On the northern side, there are many rows of graves of both sexes, with only a few having headstones.[13]

British Occupation, 1792

Gumbaz entrance (backside), Seringapatam

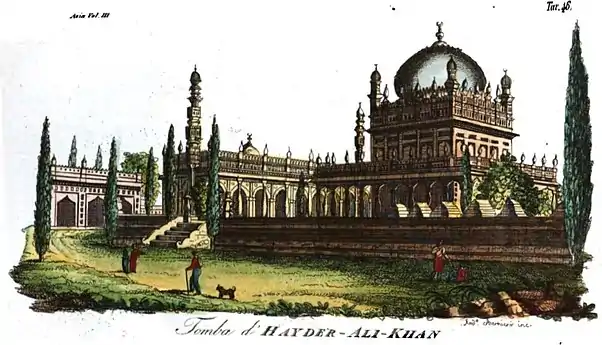

Gumbaz entrance (backside), Seringapatam Tomb of Hayder Ali, by Dottor Giulio Ferrario (1824)[14]

Tomb of Hayder Ali, by Dottor Giulio Ferrario (1824)[14]

The grounds of the Gumbaz was briefly occupied by British India forces in 1792, towards the end of the Third Anglo-Mysore War. The army camped on the grounds, and cut down many cypress trees in the garden surrounding the tomb of Hyder Ali, to be used as tent poles and fascines. The flower beds surrounding the mausoleum were dug up for the burial of those who fell in the battle. The landscaped lawns were used to exercise the horses, and the walkways used for target practice. The choultry meant for the Muslim fakirs were converted into a makeshift hospital to treat the battle wounded. These scenes were depicted in the illustrations by the military artist Charles Gold's book Oriental Drawings published in 1806. His painting shows Hyder Ali's tomb rising to the skies, but with a backdrop scene of British soldiers camping in the gardens. British forces wearing red coats with axes, cutting down the cypress trees, directing Indian workers to carry away the wood, and generally disrupting the garden.[11][15][16][17]

Charles Gold describes the scene as

The Sultan's garden... became a melancholy spectacle, devoted to the necessities of military service; and appeared for the first time as if it had suffered the ravages of the severest winter. The fruit trees were clipped of their branches; while the lofty cypress trees, broken to the ground by troops, to be formed into fascines, were rooted up by the followers to be consumed as firewood.[11][15][18]

During this occupation, the Gumbaz was sketched by military artists such as Charles Gold, James Hunter (d. 1792), Robert Home (1752-1834) and Sir. Alexander Allan (1764-1820).

Vintage Gallery

Hyder Ali's Tomb, Seringapatam by James Hunter (d.1792)[19]

Hyder Ali's Tomb, Seringapatam by James Hunter (d.1792)[19].jpg.webp) Mausoleum of Hyder Aly Khan at Lalbaug, by Robert Hyde Colebrooke, ca. 1793

Mausoleum of Hyder Aly Khan at Lalbaug, by Robert Hyde Colebrooke, ca. 1793

Mausoleum, Laul Baug, Seringapatam with tombs of Hyder Ali, his wife, and son Tippoo Saib, by Henry Jervis, Aug 1832

Mausoleum, Laul Baug, Seringapatam with tombs of Hyder Ali, his wife, and son Tippoo Saib, by Henry Jervis, Aug 1832

Robert Home's Description

Robert Home, the official military artist the Madras Army led by Lord Cornwallis, sketched the Gumbaz (see Vintage Gallery above) and described it. According to Home, the gardens called the Lal Bagh (garden of rubies), covered a third of the river island and was the largest garden in the Mysore Kingdom. The garden was landscaped beautifully with designs which was a combination of several Asian traditions, and in its middle was the mausoleum of Tipu's father Hyder Ali. He further describes the garden during the British occupation at the end of the Third Anglo-Mysore War as

This garden was laid out in regular paths of shady cypress; and abounded with fruit trees, flowers, and vegetables of every kind. But the axe of the enemy [the British] soon despoiled it of its beauties; and those trees, which once administered to the pleasures of their master, were compelled to furnish materials for the reduction of his capital.[11][15]

Tipu's Burial

_-_Copy.jpg.webp) Tipu Sultan's Tomb, Seringapatam (Caine, 1891, p. 519).[24]

Tipu Sultan's Tomb, Seringapatam (Caine, 1891, p. 519).[24]

Tipu Sultan was buried at the Gumbaz, next to the graves of his father and mother, after his death in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War in 1799.[25] The burial took place the next day after the end of the war, on 5 May 1799 at 5 May. The British allowed for Tipu to be buried at the Gumbaz, next to his father's grave, and also provided full military honours for his funeral. The body was carried in a procession, accompanied by European soldiers of the Grenadier division. The chief mourner was Tipu's son Abdul Khaliq, followed by some officials and people. A severe thunderstorm is recorded to have struck Seringapatam at the time his body was buried.

The burial of Tipu Sultan is described by many British Officers such as Lieutenant Richard Bayly of the 12th Regiment. According to Lieut. Bayly

I must relate the effects and appearance of a tremendous storm of wind, rain, thunder, and lightning that ensued on the afternoon of the burial of Tippoo Saib. I had returned to camp excessively indisposed. About five o'clock a darkness of unusual obscurity came on, and volumes of huge clouds were hanging within a few yards of the earth, in a motionless state. Suddenly, a rushing wind, with irresistible force, raised pyramids of sand to an amazing height, and swept most of the tents and marquees in frightful eddies far from their site. Ten Lascars, with my own exertions, clinging to the bamboos of the marquee scarcely preserved its fall. The thunder cracked in appalling peals close to our ears, and the vivid lightning tore up the ground in long ridges all around. Such a scene of desolation can hardly be imagined; Lascars struck dead, as also an officer and his wife in a marquee a few yards from mine. Bullocks, elephants, and camels broke loose, and scampering in every direction over the plain; every hospital tent blown away, leaving the wounded exposed, unsheltered to the elemental strife. In one of these alone eighteen men who had suffered amputation had all the bandages saturated, and were found dead on the spot the ensuing morning. The funeral party escorting Tippoo's body to the mausoleum of his ancestors situated in the Lal Bagh Garden, where the remains of his warlike father, Hyder Ali, had been deposited, were overtaken at the commencement of this furious whirlwind, and the soldiers ever after were impressed with a firm persuasion that his Satanic majesty attended in person at the funeral procession. The flashes of lightning were not as usual from far distant clouds, but proceeded from heavy vapours within a very few yards of the earth. No park of artillery could have vomited forth such incessant peals as the loud thunder that exploded close to our ears. Astonishment, dismay, and prayers for its cessation was our solitary alternative. A fearful description of the Day of Judgement might have been depicted from the appalling storm of this awful night. I have experienced hurricanes, typhoons, and gales of wind at sea, but never in the whole course of my existence had I seen anything comparable to this desolating visitation. Heaven and earth appeared absolutely to have come in collision, and no bounds set to the destruction. The roaring of the winds strove in competition with the stunning explosions of the thunder, as if the universe was once more returning to chaos. In one of these wild sweeps of the hurricane, the poles of my tent were riven to atoms, and the canvas wafted forever from my sight. I escaped without injury, as also my exhausted Lascars, and casting myself in an agony of despair on the sands, I fully expected instant annihilation. My hour was not, however, come. Towards morning the storm subsided; the clouds became more elevated, the thunder and lightning ceased, and nature once more resumed a serene aspect. But never shall I forget that dreadful night to the latest day of my existence. All language is inadequate to describe its horrors. Rather than be exposed to such another scene, I would prefer the front of a hundred battles[11][26]

Renovation by Lord Dalhousie

In 1855, Lord Dalhousie, Governor-General of India visited Seringapatam on his way to the Nilgiris. During his visit he found most of the monuments in a state of neglect, slowing falling into decay. He then ordered that buildings to be renovated and maintained, as they not only provided memories for the war for the Deccan, and the exploits of the Duke of Wellington, but were also architecturally beautiful. Lord Dalhousie also paid for the replacement doors for the Gumbaz. Dalhousie also ordered for the murals in the Daria Daulat to be restored, and the building be repaired, a sum approved for the annual maintenance of Daria Daulat, Gumbaz and other associated monuments. A minute to this effect was recorded by his staff, and a fund was established for the maintenance of these monuments at Seringapatam [28][29][30][31][32][33]

Persian Epitaphs

The Persian epitaphs at the Gumbaz were studied by Benjamin Lewis Rice and appear in his work, Epigraphia Carnatica: Volume III: Inscriptions in the Mysore District (1894)[34]

Persian Epitaphs at Gumbaz, Seringapatam, by Benjamin Lewis Rice in Epigraphia Carnatica (Vol. 3), 1894

Persian Epitaphs at Gumbaz, Seringapatam, by Benjamin Lewis Rice in Epigraphia Carnatica (Vol. 3), 1894 Roman Script of the Persian Epitaphs at Gumbaz, Seringapatam

Roman Script of the Persian Epitaphs at Gumbaz, Seringapatam English Translation of the Persian Epitaphs at Gumbaz, Seringapatam[8]

English Translation of the Persian Epitaphs at Gumbaz, Seringapatam[8]

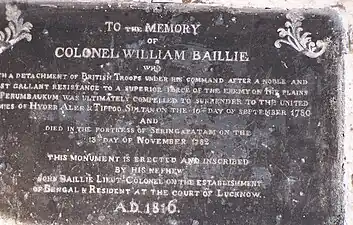

William Baillie Memorial

In the gardens of Lalbagh, next to the Gumbaz is located the memorial for William Baillie. The memorial was commissioned, 35 years after Col Baillie's death, and 17 years after the fall of Tippu Sultan, by William's nephew Lt. Col. John Baillie, who served as the British Resident in the Court of the Nawab of Oudh, Lucknow. It is an austere, but poignant and pretty structure.[35]

William Baillie Memorial, Seringapatam

William Baillie Memorial, Seringapatam Plaque of the William Baillie Memorial, Seringapatam

Plaque of the William Baillie Memorial, Seringapatam

His Majesty's Cemetery, Ganjam

According to Rev. E W Thompson and other accounts, there used to exist a Madras Army cemetery called His Majesty's Cemetery at Ganjam, near the Gumbaz (a short distance in the North-West direction), much before the Garrison Cemetery. The cemetery was enclosed by a wall, with an inscription on the gate-post, His Majesty's Cemetery, Ganjam, a.d. 1799-1808. It contains burials between 1799 and 1808, mainly from the 33rd Regiment. Daniel Pritchard, the music master of this regiment was buried at this cemetery in July 1799. Elinda Harmonci, a child aged 4 years was also buried here in November 1799.

Col. Edward Montague of the Bengal Artillery, died 8 May 1799, 4 days after the final assault is buried near the Sangam, on the extreme east end of the island.[7][36]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Everything about Srirangapatna! Gumbaz". 2010. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ Naryana, Hari (9 October 2010). "Srirangapatna – Gumbaz". India That Was ~ A Legacy Unfolded. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ Joseph, Baiju (21 July 2012). "Gumbaz - The Burial Chamber of Tipu Sultan, the Tiger of Mysore". The Home of Nostalgic Moments A Photographic Journey & Book Mark of Memories. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ "Hyder Ally's Tomb, Srirangapatam". British Library. 26 March 2009. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ "Gumbaz, Srirangapatna". Native Planet. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ "Tipu Sultan". Aulia e Hind. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- 1 2 Newell, H A (1921). Topee and Turban, or Here and There in India. London. p. 242. Archived from the original on 28 September 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 3 Rice, Benjamin Lewis (1894). Epigraphia Carnatica: Volume III: Inscriptions in the Mysore District. Mysore State, British India: Mysore Department of Archaeology. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ↑ Chopp, Chris (3 February 2012). "Srirangapatna Gumbaz: Final Resting Place for Haider Ali and Tipu Sultan". Full Stop India. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ Hariprasad, Usha (20 April 2012). "Srirangapatna, the historic island city". No. Bangalore. Citizen Matters. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Casey (29 December 2007). "Gumbaz -- Srirangapattana Mausoleum". Dream Destinations. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ "Mausoleum of Hyder Ali and Tipoo Sultan". Wesleyan Juvenile Offering. XV: 48. May 1858. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- ↑ Haroon, Anwar (29 June 2013). Kingdom of Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan: Sultanat e Khudadad. Xlibris Corporation. p. 294. ISBN 9781483615363. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ↑ Ferrario, Dottor Giulio (1824). Il costume antico e moderno o storia del governo, della milizia, della religione, delle arti scienze ed usanze di tutti i popoli antichi e moderni, Volume 3. Firenze (Florence). p. 257. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 De Almeida, Hermione; Gilpin, George H (1950). Indian Renaissance: British Romantic Art and the Prospect of India. Hants, England: Ashgate Publishing Ltd. p. 156. ISBN 075463681X. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ "Lal Bagh from Charles Gold's Oriental Drawings". Charles Gold's Oriental Drawings. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ "Charles Gold's Oriental Drawings: Lal Bagh". University of Wales. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ Gold, Charles (Capt.) (1806). Oriental Drawings: Sketched between the Years 1791 and 1798. London: G and W Nicoll (Bunney).

- ↑ Hunter, James (1792). Picturesque Scenery in the Kingdom of Mysore. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ↑ Home, Robert (1974). Select Views in Mysore, the country of Tippoo Sultan: From the Drawings Taken on the Spot by Home, With Historical Description. London: R Bowyer. p. Plate 29. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ "Hyder's tomb in the Loll Baug Gardens". British Library. 26 March 2009. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ Allen, Alexander (1 June 1794). The collection of Views in the Mysore Country. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ "Mausoleum of Hyder". British Library. 26 March 2009. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ Caine, William Sproston (1890). Picturesque India: A Handbook for European Travellers. London: London and G. Routledge & Sons, Limited. p. 519. ISBN 9781274043993. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ↑ Singh, Jangveer (7 September 2008). "On Tipu's trail". The Tribune. No. Spectrum. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ Bayly, Richard (1896). Diary of Colonel Bayly 12th Regiment :1796-1803. London: Army and Navy Co-Operative Society. pp. 95–96. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- ↑ "Tippu's Tomb, Seringapatam". Asia, Pacific and Africa Collections. British Library. 26 March 2009. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- ↑ Allen, William Osborn Bird (1885). A parson's holiday : being an account of a tour in India, Burma, and Ceylon in the winter of 1882-83. F B Mason. p. 160. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ Walsh, Robin (1999). "Gumbaz - Mausoleum". Macquarie University. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ Edmund David, Lyon (1868). "Views in Mysore. The Deria Dowlut in Seringapatam. Front of Palace and part of the garden". Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ↑ Varghese, Nina (25 January 2003). "Tipu's legacy lost in the ruins?". The Hindu: Business Line. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ↑ Prinsep, Val Cameron (1878). Glimpses of Imperial India. Mittal Publications. p. 20. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

lord dalhousie visit to seringapatam.

- ↑ Kirmani, Mir Hussain Ali Khan (1864). History of Tipu Sultan: Being a Continuation of the Neshani Hyduri. p. 162.

- ↑ Parsons, Constance E (1931). Seringapatam. H. Milford. p. 133. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ↑ Mullur, Shashikiran (22 October 2013). "Vestiges of William Baillie". No. Bangalore. Deccan Herald. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ↑ Thompson, Rev. E W (1923). The Last Siege of Seringapatam: An Account of the Final Assault, May 4th, 1799; of the Death and Burial of Tippu Sultan; and of the Imprisonment of British Officers and Men; taken from the Narratives of Officers present at the Siege and of those who survived their captivity. Mysore City, British India: Wesleyan Mission Press. pp. 68, 69. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2015.