"Tom o' Bedlam" is the title of an anonymous poem in the "mad song" genre, written in the voice of a homeless "Bedlamite". The poem was probably composed at the beginning of the 17th century. In How to Read and Why Harold Bloom called it "the greatest anonymous lyric in the [English] language."[1]

The terms "Tom o' Bedlam" and “Bedlam beggar” were used to describe beggars and vagrants who had or feigned mental illness (see also Abraham-men). Aubrey writes that such a beggar could be identified by “an armilla of tin printed, of about three inches breadth” attached to his left arm.[2] They claimed, or were assumed, to be former inmates of the Bethlem Royal Hospital (Bedlam). It was commonly thought that inmates were released with authority to make their way by begging, though this is probably untrue. If it happened at all, the numbers were small, though there were probably large numbers of mentally ill travellers who turned to begging, but had never been near Bedlam. It was adopted as a technique of begging, or a character. For example, Edgar in King Lear disguises himself as mad "Tom o' Bedlam".

Structure and verses

The poem has eight verses of eight lines each, each verse concluding with a repetition of a four-line chorus. The existence of a chorus suggests that the poem may originally have been sung as a ballad. The version reproduced here is the one presented in Bloom's How to Read and Why.[3]

In the Book of Moons, defend ye!"

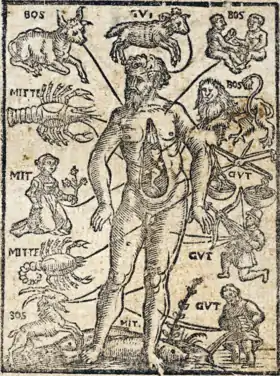

Zodiac man, from a 1580 almanac

Tom o' Bedlam

From the hag and hungry goblin

That into rags would rend ye,

The spirit that stands by the naked man

In the Book of Moons defend ye,

That of your five sound senses

You never be forsaken,

Nor wander from your selves with Tom

Abroad to beg your bacon,

While I do sing, Any food, any feeding,

Feeding, drink, or clothing;

Come dame or maid, be not afraid,

Poor Tom will injure nothing.

Of thirty bare years have I

Twice twenty been enragèd,

And of forty been three times fifteen

In durance soundly cagèd

On the lordly lofts of Bedlam,

With stubble soft and dainty,

Brave bracelets strong, sweet whips ding-dong,

With wholesome hunger plenty,

And now I sing, Any food, any feeding,

Feeding, drink, or clothing;

Come dame or maid, be not afraid,

Poor Tom will injure nothing.

With a thought I took for Maudlin

And a cruse of cockle pottage,

With a thing thus tall, sky bless you all,

I befell into this dotage.

I slept not since the Conquest,

Till then I never wakèd,

Till the roguish boy of love where I lay

Me found and stript me nakèd.

And now I sing, Any food, any feeding,

Feeding, drink, or clothing;

Come dame or maid, be not afraid,

Poor Tom will injure nothing.

When I short have shorn my sow's face

And swigged my horny barrel,

In an oaken inn I pound my skin

As a suit of gilt apparel;

The moon's my constant mistress,

And the lowly owl my marrow;

The flaming drake and the night crow make

Me music to my sorrow.

While I do sing, Any food, any feeding,

Feeding, drink, or clothing;

Come dame or maid, be not afraid,

Poor Tom will injure nothing.

The palsy plagues my pulses

When I prig your pigs or pullen,

Your culvers take, or matchless make

Your Chanticleer or Sullen.

When I want provant with Humphrey

I sup, and when benighted,

I repose in Paul's with waking souls

Yet never am affrighted.

But I do sing, Any food, any feeding,

Feeding, drink, or clothing;

Come dame or maid, be not afraid,

Poor Tom will injure nothing.

I know more than Apollo,

For oft, when he lies sleeping

I see the stars at bloody wars

In the wounded welkin weeping;

The moon embrace her shepherd,

And the Queen of Love her warrior,

While the first doth horn the star of morn,

And the next the heavenly Farrier.

While I do sing, Any food, any feeding,

Feeding, drink, or clothing;

Come dame or maid, be not afraid,

Poor Tom will injure nothing.

The gypsies, Snap and Pedro,

Are none of Tom's comradoes,

The punk I scorn and the cutpurse sworn,

And the roaring boy's bravadoes.

The meek, the white, the gentle

Me handle, touch, and spare not;

But those that cross Tom Rynosseros

Do what the panther dare not.

Although I sing, Any food, any feeding,

Feeding, drink, or clothing;

Come dame or maid, be not afraid,

Poor Tom will injure nothing.

With a host of furious fancies

Whereof I am commander,

With a burning spear and a horse of air,

To the wilderness I wander.

By a knight of ghosts and shadows

I summoned am to tourney

Ten leagues beyond the wide world's end:

Methinks it is no journey.

Yet will I sing, Any food, any feeding,

Feeding, drink, or clothing;

Come dame or maid, be not afraid,

Poor Tom will injure nothing.

"Mad Maudlin's Search"

The original ballad was popular enough that another poem was written in reply: "Mad Maudlin's Search" or "Mad Maudlin's Search for Her Tom of Bedlam"[4] (she may be meant to be the Maud who seems to be mentioned in the verse "With a thought I took for Maudlin / And a cruise of cockle pottage / With a thing thus tall, Sky bless you all / I befell into this dotage." which apparently records Tom going mad) or "Bedlam Boys" (from the chorus, "Still I sing bonny boys, bonny mad boys / Bedlam boys are bonny / For they all go bare and they live by the air / And they want no drink or money."), whose first stanza is:

- For to see Mad Tom of Bedlam,

- Ten thousand miles I've traveled.

- Mad Maudlin goes on dirty toes,

- For to save her shoes from gravel

The remaining stanzas include:

- I went down to Satan's kitchen

- To break my fast one morning

- And there I got souls piping hot

- All on the spit a-turning.

- There I took a cauldron

- Where boiled ten thousand harlots

- Though full of flame I drank the same

- To the health of all such varlets.

- My staff has murdered giants

- My bag a long knife carries

- To cut mince pies from children's thighs

- For which to feed the fairies.

- No gypsy, slut or doxy

- Shall win my mad Tom from me

- I'll weep all night, with stars I'll fight

- The fray shall well become me.

[5][6]

It was apparently first published in 1720 by Thomas d'Urfey in his Wit and Mirth, or Pills to Purge Melancholy. "Maudlin" was a form of Mary Magdalene.

Because of the number of variants of each poem, and confusion between the two, neither "Tom o' Bedlam" nor "Mad Maudlin" can be said to have definitive texts.[7]

The folk-rock band Steeleye Span recorded "Boys of Bedlam", a version of "Mad Maudlin", on their 1971 album Please To See The King. Steeleye recorded a very different arrangement on Dodgy Bastards (2016), which included a rap section and a bassline that set the song in the Phrygian mode.

In modern culture

- Lin Carter included the poem in his 1969 fantasy anthology Dragons, Elves, and Heroes.

- Tom o' Bedlam is the name Edgar gives in Shakespeare's King Lear when he pretends to be a mad vagrant. It is also to be found in a case before Star Chamber in 1632 when a Sussex man complains of being defamed in a set of verses sung in the ale houses of Rye to the tune of Tom o' Bedlam, further indication that it was a ballad.

- Kenneth Patchen's surrealist novel The Journal of Albion Moonlight is loosely based on and makes frequent reference to the poem.

- Robert Silverberg's science fiction novel Tom O' Bedlam (1985) includes several quotations from the poem. The main character also calls himself by that name.

- John Brunner's 1968 novel Bedlam Planet prefaces each chapter with entire stanzas from the poem, titling the chapter after the subject of the stanza.

- Mercedes Lackey has co-authored a series of books whose titles are taken from verses of the poem.

- Parts of Derek Walcott's poem, The Bounty (1997), are addressed to "mad Tom."

- Folk rock band Steeleye Span set the poem to music on the album Please to See the King.

- Jolie Holland recorded a version of Maudlin's song titled "Mad Tom of Bedlam" on her 2004 album Escondida. Charlene Kaye also recorded this version for her The Brilliant Eyes EP.

- Old Blind Dogs a traditional Scottish band recorded a version titled "Bedlam Boys" on their 1992 debut album New Tricks and a new arrangement on their 2004 album Four on the Floor.

- A recording of the poem sung in the style of a tavern song is included in the soundtrack of the video game Stronghold 3. For unknown reasons, the line "Ten thousand miles I've traveled" was changed to "Ten thousand years I travel".

- An incidental character in Rosemary Sutcliff's Brother Dusty-Feet is called "Tom o' Bedlam" and sings this poem (anachronistically: Brother Dusty-Feet is set in the reign of Queen Elizabeth), of which only the last verse (without the refrain) occurs in the text.

- In "Assassin's Creed: Syndicate", a video game from 2015, there are 31 hidden music boxes scattered throughout 1868 London's streets. When one goes to the Progression Log and look under "Secrets Of London", they can see the locations of each of the 31 music boxes as a screenshot showing the box and whatever is nearby, leaving it up to the player to figure out exactly where it is. Additionally, each entry is accompanied by a 4-line quote from "Tom o' Bedlam".

References

- ↑ Harold Bloom at Charlie Rose

- ↑ The National Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge, Volume 3, London: Charles Knight, 1847, p.86.

- ↑ Bloom, Harold (2000). How to Read and Why. New York: Scribner. pp. 104–107. ISBN 0-684-85906-8.

- ↑ "minstrel: Tom of Bedlam...." Archived October 25, 2004, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Tom o' Bedlam "

- ↑ "Bedlam Boys"

- ↑ "minstrel: Tom o' Bedlam, Calino" Archived February 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- Loving Mad Tom: Bedlamite verses of the XVI and XVII centuries; with five illustrations by Norman Lindsay; the texts edited with notes by Jack Lindsay; musical transcriptions by Peter Warlock. London: Fanfrolico Press, 1927

External links

- Comments by Isaac D'Israeli in "Curiosities of Literature"