| Toque macaque[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Cercopithecidae |

| Genus: | Macaca |

| Species: | M. sinica |

| Binomial name | |

| Macaca sinica (Linnaeus, 1771) | |

| |

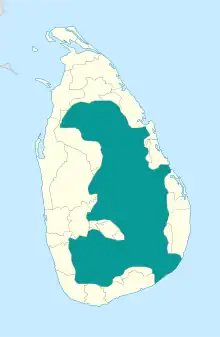

| Toque macaque range map | |

_juvenile.jpg.webp)

The toque macaque (/tɒk məˈkæk/; Macaca sinica) is a reddish-brown-coloured Old World monkey endemic to Sri Lanka, where it is known as the rilewa or rilawa (Sinhala: රිළවා), (hence "rillow" in the Oxford English Dictionary). Its name refers to the whorl of hair at the crown of the head, reminiscent of a brimless toque cap.[3]

Taxonomy

The generic name Macaca is from Portuguese macaco, of unclear origin, while sinica means "of China," even though the species is not found there.[4]

There are three recognized subspecies of toque macaques:[2]

- Macaca sinica sinica, dry zone toque macaque or common toque macaque

- Macaca sinica aurifrons, wet zone toque macaque or pale-fronted toque macaque

- Macaca sinica opisthomelas, highland toque macaque or hill zone toque macaque

M. s. opisthomelas is similar to subsp. aurifrons, but has a long fur and contrasting golden color in the anterior part of its brown cap.

The three subspecies can be identified their head colour patterns.[5]

Description

With age, the face of females turns slightly pink. This is especially prominent in the subspecies M. s. sinica.

Distribution

M. s. sinica is found from the Vavuniya, Mannar to the lowlands of Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa, Puttalam, and Kurunegala; and along the arid zone of the Monaragala and Hambantota districts.

M. s. aurifrons can be found sympatrically with the subspecies M. s. sinica within intermediate regions of the country in Kegalle and parts of Kurunegala. It is also found in south-western parts of the island in the Galle and Matara districts near Kalu Ganga.

M. s. opisthomelas has recently been identified as a separate subspecies. It can be found in the entire south-western region of Ratnapura and in the Nuwara Eliya districts. It is also found around Hakgala Botanical Garden and other cold climatic montane forest patches.[6]

Behaviour and ecology

Social structure

Social status is highly structured in toque macaque troops and dominance hierarchies occur among both males and females. A troop may consist of eight to forty individuals. When the troop becomes too large, social tension and aggression towards each other rises, causing some individuals to leave. This is noticeable in adults and sub adults, where a troop may consist largely of females. Newly appointed alpha males show aggressiveness towards females, causing the females to leave the group. Fighting within the troop can cause serious injuries including broken arms.[6]

Young offspring of a troop's alpha female will typically receive better sustenance and shelter than their peers.[7]

Reproduction

.jpg.webp)

When in estrous, the female's perineum becomes reddish in color and swells. This signals to males that she is ready to mate. There is an average of 18 months between births. After a 5–6 month gestation period, the female will give birth to a single offspring. The baby will hold on to its mother for about 2 months. During this time the infant learns social skills critical for survival. The infant will inherit its social standing from its mother's position in the troop. Young males are forced to abandon their troop when they are about 6–8 years of age. This prevents inbreeding and ensures that the current alpha male maintains his position in the troop. Leaving the troop is the only way a male can change his social standing. If he has good social skills and is strong he may become an alpha male. A single alpha male can father all of the troops' offspring.[6]

Birth rarely occurs during the day or on the ground. During labor the female isolates herself from the group (about 100 m). The mother stands bipedally during parturition and assists the delivery with her hands. The infant is usually born 2 minutes after crowning. The infant can vocalize almost immediately after birth; it is important for the mother and infant to recognize each other's voices. Vocalization will be used to alert the mother of imminent danger, and can assist in finding each other if separated. After birth the mother licks the infant and orients it toward her breasts. She will resume foraging behavior within 20 minutes after parturition. The mother also eats part of the placenta, because it contains needed protein. The alpha female of the group asserts her power by taking part of the placenta for herself to eat.[8]

Diet

One study of toque macaques recorded a diet of 14% flowers, 77% fruits, 5% mushrooms, and 4% prey items. The preferred fruit species included Ficus bengalensis, Glenniea unijuga, Schleichera oleosa, Drypetes sepiaria, Grewia polygama, Ficus amplissima, and Ficus retusa. It was found that mushrooms were much sought after during the wet season.[9]

Cheek pouches enable toque macaques to store food while eating fast. In the dry zone, they are known to eat drupes of the understory shrub Zizyphus and ripe fruits of Ficus, and Cordia species. They occasionally eat small animals ranging from small insects to mammals like the Indian palm squirrel and the Asiatic long-tailed climbing mouse.[6]

Predators

Wild cats (leopards and fishing cats) and Indian rock python are the main predators of this species.

Conservation

The toque macaque is listed as Endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) due to habitat destruction and hunting, and also for the pet trade. Much of the original forested habitat of the toque macaque has been lost, between 1956 and 1993 50% of Sri Lanka's forest cover was destroyed. Plantations and fuel wood collection have been the main drivers of habitat lost. Toque macaques were also used by both Sri Lanka Army and Tamil Tigers as target practice during the Sri Lankan Civil War.[2] The recent move by the Sri Lankan government to export 100000 monkeys to China has raised opposition from conservationists and zoologist from the island country.[10]

Both subspecies M. s. aurifrons and M. s. sinica are kept as pets.[2]

Antibody prevalence

In an experiment, serum samples taken from toque macaque individuals at Polonnaruwa were examined for antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii by the modified agglutination test. There was no evidence of maternal transmission of antibodies or congenital toxoplasmosis. None of the infected macaques died within 1 year after sampling. Toxoplasma gondii infection was closely linked to human environments where domestic cats were common. Although infection with T. gondii has been noted in several species of Asian primates, this is the first report of T. gondii antibodies in toque macaques.[11]

References

- ↑ Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 164. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- 1 2 3 4 Dittus, W.; Watson, A.C. (2020). "Macaca sinica". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T12560A17951229. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T12560A17951229.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ↑ "Toque macaque". New England Primate Conservancy. 14 December 2021.

- ↑ "Wildlife Review". U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service. February 9, 1993.

- ↑ Fooden, Jack (1979). "Taxonomy and evolution of the sinica group of macaques: I. Species and subspecies accounts of Macaca sinica". Primates. 20: 109–140. doi:10.1007/BF02373832. S2CID 27742337.

- 1 2 3 4 Yapa, A.; Ratnavira, G. (2013). Mammals of Sri Lanka. Colombo: Field Ornithology Group of Sri Lanka. p. 1012. ISBN 978-955-8576-32-8.

- ↑ "Animal Babies: First Year on Earth" – via www.pbs.org.

- ↑ Ratnayeke, A. P.; Dittus, W. P. J. (1989). "Observation of a birth among wild toque macaques (Macaca sinica)". International Journal of Primatology. 10 (3): 235–242. doi:10.1007/BF02735202. S2CID 40473283.

- ↑ Hladik, C.M.; Hladik, A. (1972). "Disponibilites alimentaires et domaines vitaux des primates a Ceylan". La Terre et la Vie (in French). 26: 149–215. doi:10.1007/BF02373832. S2CID 27742337.

- ↑ Srinivasan, Meera (19 April 2023). "Conservationists in Sri Lanka slam proposal to export monkeys to China". www.thehindu.com. The Hindu. Archived from the original on April 19, 2023. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- ↑ Ekanayake, D. K.; Rajapakse, R. P. V. J.; Dubey, J. P.; Dittus, W. P. J. (2004). "Seroprevalence of "'Toxoplasma gondii in wild toque macaques (Macaca sinica) at Polonnaruwa, Sri Lanka". Journal of Parasitology. 90 (4): 870–871. doi:10.1645/GE-291R. PMID 15357087. S2CID 23829241.