| Mirandola Town Hall | |

|---|---|

| |

| General information | |

| Town or city | Mirandola |

| Inaugurated | c. 1468 |

| Destroyed | 2012 |

| Owner | Municipality of Mirandola |

The Mirandola Town Hall (Italian: Palazzo Comunale di Mirandola; in the local dialect: al palàzz cumunàl ad La Miràndla or simply al Cumùn or al Munizìpi) is a historic public building located in the city center of Mirandola, in the province of Modena, Italy.

Seat of the city government until May 2012, the building is dramatically located at the end of Costituente square and is one of the most recognizable icon of the city of Mirandola, along with the castle of the Pico.

History

Origins

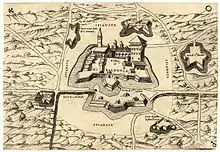

The origins of the medieval palace are not known, despite the fact that the building is one of the most important in the socio-political-economic history of the city. It can be assumed that the palace was probably built in the mid of 15th century[1] by Gianfrancesco I Pico, who began the first phase of urban development of Mirandola.[2]

In any case, it is certain that during the Renaissance the Countess Giulia Boiardo (mother of famous philosopher Giovanni Pico della Mirandola) had built a loggia[3] in what was then called Palace of Merchandise (Palazzo della Mercanzia) or Palace of Reason (Palazzo della Ragione). In fact, on the eastern facade of Curtatone street there is the following inscription:

IULIA BOIARDO PICO COM(itissa) MIR(andulæ) |

Giulia Boiardo Pico, Countess of Mirandola |

To build this loggia, a tax of eight quattrins was instituted for each biolca (2933.63 m²) of land owned; however, since the works cost less than expected, the advanced money was returned.[4]

In 1514 the possession of the city was returned, after a quarrel with the brothers, to Giovanni Francesco II Pico della Mirandola: the ceremony took place right under the loggia of the Palazzo della Ragione. In 1573, on the occasion of a dispute between the guardians of the heirs of Ludovico II Pico, a document was read in public under the loggia of the Palazzo della Ragione, opposite the square.

No other evidence can be found until the 18th century, although the palace is well recognizable in the topographic maps of the 16th-17th centuries.

18th century

In 1783-1784 the southern portico of the present Giuseppe Mazzini square was built in order to house the grain market (gabella de' grani).

On July 10, 1798, the marble statue of the so-called People's Madonna (Madonna del Popolo, also known as the Madonnina), which was located in a niche on the northern facade and which was brought to the Cathedral of Santa Maria Maggiore.[5] The statue was later placed on the tympanum of the Oratory of the Blessed Virgin of the Gate, from which it was temporarily removed following the 2012 earthquake.

In a watercolour by Giovanni Battista Menabue depicting a conflict that occurred in the square of Mirandola on April 27, 1799 between Germans, Cisalpines and Mantuans (exposed at the Civic Museum of the Risorgimento of Modena), it can be noticed, at the center of the facade of the building, the empty niche in which the statue of the Madonna was placed. This niche was closed with the restoration works of 1868.

19th century

In 1837 the mayor, Count Felice Ceccopieri, had the clock of the square tower moved onto the roof of the town hall, installing it on a simple metal scaffolding.

In the mid of 19th century the arches of the facade collapsed and some consolidation works were necessary, which later led to a greater restoration in 1868 by the engineer Felice Poppi. These consolidation works were not so effective, so that only three years later there were detachments of rubble. The municipal administration was forced to intervene urgently, entrusting the municipal engineer Alberto Vischi, who decided to demolish and completely remake all the facade, embellishing it with decorative terracotta. Being an economically very demanding intervention (the estimated expenditure amounted to 11,000 lire at the time), the administration delayed the start of work for almost 20 years until it was inevitable given the worsening situation.

20th century

On June 3, 1901, the start of the works was finally decided and officially started on June 29, 1901: the loggia was propped up, while the vertical walls were demolished and the bricks brought to Cividale, to be reused to build the new station on the Bologna-Verona railway (inaugurated in 1902). In the end, the restoration cost a total of 18,669 lire.

In 1925-1930, during the Fascist period, the great internal marble staircase was built.

Other restoration and consolidation works date back to 1968–1970 (replacement of the wooden beams of the floors with steel beams). In 1978 there were other works on the top floor. In the following years, the former apartment of the guardian located on the mid-floor housed first the registry office and then technical offices of the city administration. In 1998-1999 other works of adaptation and functional improvement of the spaces were carried out.

21st century

Following the disastrous 2012 Northern Italy earthquakes, the town hall suffered serious damage, so much so that the municipal administration was forced to build a new municipal headquarters in the western outskirts of the city.

In 2013 the planning of the restoration works was started, with a cost of 625,038.23 euro.[6]

As 2019, seven years after the earthquake of May 2012, the town hall is still propped up and uninhabitable, and restoration work has not yet begun, estimated at 7,450,708 euros.[7]

Architecture

The palace has a load-bearing masonry structure with a quadrangular plan 18 m long and 14 m wide, which develops over a height of 16 m divided into four floors above ground (ground, mezzanine, first, and attic).[8]

The entire building is visually divided vertically into three parts in an east-west direction, corresponding to the three different phases of construction: the Renaissance loggia, the medieval core and the 18th century southern portico.

Exteriors

Northern facade (Loggia of the Pico)

The front facade, also called Loggia of the Pico, is the most interesting architectural part, as it was built in Renaissance style. The facade is not perfectly aligned with the square, but is slightly oriented to the left, so that the windows of the Great Hall (Sala Granda) can see directly the castle of the Pico, at the opposite side of Costituente square.

The lower part of the facade consists of a high portico, with eleven columns in Verona pink marble[9] that support frontally six round arches, two of which are deep laterally. On the inner side of some columns, under the portico, are engraved the ancient units of measure of the Mirandola district: pole (pertica), arm (braccio), foot (piede), as well as the shape of a brick and a tile. On the wall of the building there is an opening, locked by a wrought iron gate, which leads to the internal staircase that leads to the upper floors, next to the gate, there are three and two doors, respectively, to the municipal offices and the coffeehouse. There is a marble medallion with the effigy of Francesco Montanari (Colonel of Mirandola who died during the expedition of the Thousand) and some commemorative plaques of Filippo Corridoni (1898), of the partisans who died during the Resistance in the Second World War and the anniversary of the award of the title of City (1597–1997).

The upper part of the north facade, made of exposed bricks, is decorated with four biforas with marble columns and a French window, all embellished with terracotta friezes with floral and zoomorphic motifs, similar to those of the nearby Bergomi Palace. The biforas, which have Russian-style sliding shutters that enter the cavity of the wall, are placed symmetrically and in line with the columns of the portico below. The masonry part is framed at the bottom by a double belt course and at the top by eaves, also in terracotta. The whole arrangement makes the appearance of the facade harmonious, at the centre of which is a marble balcony, surmounted by the coat of arms of the community of Mirandola.

From the base of the palace starts a long walkpath called Listone (about 242 m, 4 m wide), made of porphyry cubes of the Bolognese type and that crosses longitudinally the entire Constituent square, up to the Oratory of the Madonnina. Walking along the Listone, back and forth along the square, is a traditional custom of Mirandola citizenship.

Clock

.jpg.webp)

In 1836 the "gabella de' birri" was demolished and a building was built in its place that covered the view of the ancient Square Tower (also called Tower of the Hours, later demolished in 1888).

The mayor of Mirandola, Count Felice Ceccopieri, decided in 1837 to transfer the clock on the roof of the town hall, after resizing the dial, which was installed on a simple metal frame flush with the facade. During the restoration works at the beginning of the 20th century it was decided to create a stone clock exhibition with a new glass dial divided into 12 triangles with black and red numbers and night gas lighting. The new dial installed in 1905, however, was not appreciated because, being transparent, at night did not show well the hands that were confused with the numbering, so it was necessary to replace the glass dial with the current one.

The dial of the watch, in frosted glass with Roman numerals and illuminated at night, is enclosed in a square case in hen stone (Verona tuff limestone), supported at the sides by two carved griffins. On the back of the clock there is a masonry work that ends in the double bell cell, where two bells are placed: one of them is used for the tolling of the hours, while the other bell (which now marks the quarters of an hour) was originally placed to announce to the citizens that the new notices issued by the municipal administration were posted on the court register.

On the morning of May 29, 2012, the clock in the square stopped at 9:05 a.m., when the second major seismic shock (magnitude 5.8) of the 2012 earthquake[10] The clock hands stood still for two years, until it was symbolically reactivated on May 20, 2014, on the second anniversary of the earthquake.[11]

Southern facade

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

The southern facade was built in a simple way by Angelo Scarabelli Pedoca between September 1783 and 1784, when it was decided to demolish the houses that supported the town hall in order to create the "gabella de' grani" (grain market).

The facade is substantially identical to the original eighteenth century, with seven large round arches plus two lateral, supported by square brick columns.

On the ground floor, there is a large doorway which leads to a corridor communicating with the entrance on the opposite side and a staircase leading to the mezzanine floor and the horizontal floor located in the middle of the first ramp of the internal staircase.

On the first floor, there are six rectangular windows and a French window leading to a small terrace with a cast-iron railing.

Initially, the new square was simply called "Piazzetta Nuova" (1786), while in 1865 it was named Piazza Montanara, in memory of the famous battle of Montanara fought on 29 May 1848 during the first war of independence.[12]

In 1930 or 1931, near the south-eastern corner of the palace, the large newspaper kiosk was built on 23 June 1906 in Belle Époque style and in wrought iron and glass, which was initially located in Modena, first in Piazza Grande (between the apse of the Duomo of Modena and the Ringadora stone) and then in Alessandro Tassoni square.[13]

Interiors

Staircase

During the Fascist period, the increase in the municipal administrative functions made it necessary to distribute the offices differently, so that in 1925-1930 it was decided to carry out various works of improvement. In particular, in the inner courtyard of the palace, on December 13, 1928, work began to create an imposing white marble staircase in eclectic and monumental style, designed by the architect Mario Guerzoni.

The new-Renaissance decorations of the staircase were inspired by those of the Stanga Palace in Cremona.

The courtyard and the staircase were also closed by an iron roof with yellow and blue glass (official colours of Mirandola).

The work was completed on October 3, 1929, with a final expenditure of 368,351.60 lire.

Yellow Hall

The Yellow Hall (Sala Gialla), so called because of the color of its walls, is located on the west side overlooking the Palace alley and is communicating with the Great Hall on one side and the mayor's office on the other side.

In this room, until 2012, the City Council met and was also used for small events and meetings that did not require the large spaces of the Great Hall.

Great Hall

The Great Hall (Sala Granda), as its name suggests, is the largest room in the entire building and is located above the loggia of the Pico.

It was built during the works of 1928-1929, demolishing the walls that separated three distinct rooms. The room is decorated with an elegant inlaid wooden coffered ceiling, from which hang wrought iron chandeliers.[14]

Until the reopening of the castle and the civic museum, it housed the paintings of the Pico family and other paintings from the churches of Mirandola. In the hall was also placed the large painting (450x250 cm) by the Neapolitan painter Raffaello Tancredi depicting Pope Julius II during the siege of Mirandola in 1511. On July 27, 2012, the fire brigade extracted some of the paintings kept in the Great Hall, including the Fall of St. Paul by Sante Peranda, the Adoration of the Three Kings by Palma il Giovane and St. Agata by Pietro Faccini;[15] the saved works of art were then taken to the restoration centre set up at the Ducal Palace of Sassuolo.[16]

Before the 2012 earthquake the Great Hall was used as a reception room, for municipal council meetings, civil marriages, events and conferences. In November, on the occasion of the Franciacorta market fair, the mayor met the "prince" with his court of ambassadors, nobles and dignitaries of the folkloristic Principality of Franciacorta, who came "to establish diplomatic relations" following the "independence" of the eastern quarter of the city, which is traditionally declared during the three days of the event. The court of nobles, however, is used to declare bankruptcy and reoccurrence on time the following year. On the occasion of the Carnival, speeches were given from the balcony overlooking the square by various people, including the Modenese masks of Sandrone with the Pavironica family.

New town hall

Following the 2012 Emilia earthquake, the historic town hall in Costituente square was severely damaged and in 2019 is still unusable, as the restoration work has not yet been assigned.

Pending the recovery of the historic headquarters and in order not to interrupt the administrative activity, after an initial emergency arrangement of the municipal offices in the containers of the temporary housing modules, on September 21, 2013 was inaugurated the new town hall of Mirandola, located on the western outskirts of the city, in Giovanni Giolitti street.[17]

The new town hall was built in reinforced concrete, costing 5 million euros,[18] and has an area of 3,800 m² and 114 offices that house about 220 employees, and was designed and built in six months,[19] of which only 137 days for the works.[20]

In addition, other projects for the recovery of several large public buildings in the historic center of Mirandola damaged by the 2012 earthquake (including the Palace of the Fascist Militia), were to bring back the municipal offices, are also being studied. As of October 2019, however, restoration work of the buildings had not yet begun.

References

- ↑ Mirandola entry (in Italian) in the Enciclopedia italiana

- ↑ Vilmo Cappi (1973). La Mirandola: storia urbanistica di una città. Modena: Poligrafico Artioli per la Cassa di Risparmio di Mirandola. p. 16.

- ↑ "I restauri della loggia dei Pico". Al Barnardon. 2016-03-22.

- ↑ Felice Ceretti (1874). Intorno al P. Francesco Ignazio Papotti ed ai suoi Annali della Mirandola. Memorie storiche mirandolesi. Vol. III. Mirandola: Cagarelli. p. XXVI.

- ↑ Vanni Chierici (2016-06-30). "La Chiesa della Madonnina". Al Barnardon.

- ↑ "Mirandola, bando per la progettazione del palazzo municipale". Modena Today. 2013-09-04.

- ↑ "27 Sono i progetti di recupero". Al Barnardon. 2016-12-02.

- ↑ Giancarlo Maselli. "Mirandola - Palazzo Municipale". Giancarlo Maselli Diagnostica & Engineering. Archived from the original on 2017-04-07. Retrieved 2014-04-07.

- ↑ Modena e provincia: le regge del ducato estense, Carpi, Vignola, Nonantola. Milano: Touring Club Italiano. 1999. p. 69. ISBN 88-365-1355-7.

- ↑ L'intero centro di Mirandola è zona rossa.

- ↑ Filomena Fotia. "Terremoto in Emilia: riattivato l'orologio del palazzo municipale di Mirandola". meteoweb.

- ↑ Vanni Chierici (2015-11-27). "Mirandola – P.zza Mazzini – V.lo del Palazzo". Al Barnardon.

- ↑ Giuseppe Morselli (1985). "Un'edicola in salotto". Al Barnardon.

- ↑ "Mirandola - La storia". Visit Modena. Retrieved 2017-04-07.

- ↑ "Terremoto, arte a rischio: salvati dipinti nel municipio di Mirandola E si riduce ancora la 'zona rossa'". Il Resto del Carlino. 2012-07-28.

- ↑ "Salvati i preziosi quadri del Municipio". Indicatore Mirandolese. Vol. 17, no. 13. August 2012. p. 5.

- ↑ "Inaugurato il nuovo municipio di Mirandola". YouReporter. 2013-09-21.

- ↑ "Sabato 21 settembre inaugura il nuovo municipio". L'Indicatore mirandolese. 2013-08-05.

- ↑ "Municipio di Mirandola". Archilinea. 2013. Archived from the original on 2017-04-06.

- ↑ "Classe A e antisismica per il nuovo municipio di Mirandola". Sassuolo 2000. 2013-09-20.

Bibliography

- Carlo Caleffi (1999). Gruppo Studi Bassa Modenese (ed.). Il Palazzo comunale di Mirandola: ricerche storico-archivistiche sui restauri dell'edificio dalla fine del Settecento ad oggi (in Italian). Mirandola-San Felice sul Panaro. p. 158.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)