| Yellow-bellied slider | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

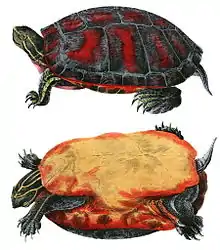

| Female yellow-bellied slider | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Testudinoidea |

| Family: | Emydidae |

| Genus: | Trachemys |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | T. s. scripta |

| Trinomial name | |

| Trachemys scripta scripta | |

| |

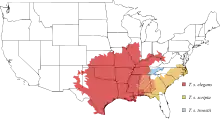

| The ranges of the three subspecies of pond slider. The yellow-bellied slider is in yellow. | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

The yellow-bellied slider (Trachemys scripta scripta) is a land and water turtle belonging to the family Emydidae. This subspecies of pond slider is native to the southeastern United States, specifically from Florida to southeastern Virginia,[4] and is the most common turtle species in its range.[5] It is found in a wide variety of habitats, including slow-moving rivers, floodplain swamps, marshes, seasonal wetlands, and permanent ponds.[6] Yellow-bellied sliders are popular as pets. They are a model organism for population studies due to their high population densities. [7]

Description

Adult male yellow-bellied sliders typically reach 5–9 inches (13–23 cm) in length; females range from 8–13 inches (20–33 cm).[8] The carapace (upper shell) is typically brown and black, often with yellow stripes. The skin is olive green with prominent patches of yellow down the neck and legs. As the name implies, the plastron (bottom shell) is mostly yellow with black spots along the edges. Adults tend to grow darker as they age.[9][10] Yellow-bellied sliders are often confused with eastern river cooters, who also have yellow stripes on the neck and yellow undersides, but the latter lack the green spots characteristic of this species. The yellow belly often has an "s"-shaped yellow stripe on its face. They also have markings shaped like question marks on their bellies. Females of the species reach a larger body size than the males do in the same populations.[11]

Distribution

Yellow-belly sliders range from southeastern Virginia through the coastal plains of the Carolinas, Georgia, northern Florida, and eastern Alabama. [12] In European countries where pond sliders are established and invasive, that they can impose threats to native biodiversity through competitive advantage over native terrapins. [13]

Reproduction

Mating can occur in spring, summer, and autumn. They have polygynandrous mating behavior. Courtship consists of biting, foreclaw display, and chasing. [14] Yellow-bellied sliders are capable of interbreeding with other T. scripta subspecies, such as red-eared sliders, which are commonly sold as pets. The release of non-native red-eared sliders into local environments caused the state of Florida to ban the sale of red-eared sliders in order to protect the native population of yellow-bellied sliders.[15]

Mating takes place in the water. Suitable terrestrial area is required for egg-laying by nesting females, who will normally lay 6–10 eggs at a time, with larger females capable of bearing more. The eggs incubate for 2–3 months and the hatchlings will usually stay with the nest through winter. Hatchlings are almost entirely carnivorous, feeding on insects, spiders, crustaceans, tadpoles, fish, and carrion. As they age, adults eat less and less meat, and up to 95% of their nutritional intake eventually comes from plants.[10]

Movement

Yellow-bellied slider movement is highly instigated by dry seasons, where they can be found traveling terrestrially to locate a new water source.[16] One study also found movement is also highly motivated by reproductive recruitment. Differences between male and female movements were observed. Males were more active than females in spring to the end of autumn. Males also exhibited more terrestrial and aquatic movements than females. Finally, long periods of movements were exclusively males.[17]

Feeding behavior

The slider is considered a diurnal turtle; it feeds mainly in the morning and frequently basks on shore, on logs, or while floating, during the rest of the day. At night, it sleeps on the bottom or on the surface near brush piles. Highest densities of sliders occur where algae blooms and aquatic macrophytes are abundant and are of the type that form dense mats at the surface, such as Myriophyllum spicatum and lily pads (Nymphaeaceae). Dense surface vegetation provides cover from predators and supports high densities of aquatic invertebrates and small vertebrates, which offer better foraging than open water.[18]

Hatchlings are primarily carnivorous and feed on insects, spiders, crustaceans, and tadpoles. Adults prefer a more high-protein diet but can sustain a vegetative diet. Adult diets consist of leaves, stems, roots, fruits, larger invertebrates, small fish, tadpoles, and frogs. [19]

Predators

Some common predators of the yellow-bellied slider include raccoons, opossums, red foxes, and skunks. Other than predators, yellow-bellied sliders are susceptible to respiratory infections which can cause wheezing, drooling, or puffiness in the eyes and is commonly caused by bacteria. Additionally, these turtles can develop fungal spores that can lead to shell rot, they can also develop metabolic bone disease which can stunt the growth of their shells and cause them to be more brittle and prone to damage [20]

Lifespan

The lifespan of yellow-bellied sliders is over 30 years in the wild,[21] and over 40 years in captivity.[10]

Since yellow-bellied sliders are long-lived organisms, they require high survivorship to maintain stable populations. They are particularly susceptible to negative effects associated with anthropogenic habitat modification such as increased presence of human-subsidized predators and increased road mortality. Recruitment could also be decreased in populations in highly urbanized areas due to a decrease in habitat connectivity and potential nesting sites.[22]

As pets

Housing

Baby yellow-bellied sliders may be kept in a fairly small tank (20 to 40 gallons), but as they age, after about three years, they will require much more space. One adult may be housed in a 75 US gal (284 L) or larger aquarium. The turtles require enough water to turn around, with a depth of 16–18 in (41–46 cm) recommended. Water temperature should be kept between 72 and 80 °F (22–27 °C) and properly filtered.[10] Keeping fish with turtles is usually avoided due to the risk that the turtle will eat the fish. Sliders need a basking area that is kept warm during the day and that will allow the turtle to move around, balance, and dry off completely. This area should average 89–95 °F (32–35 °C) and can be heated with a UV-A heat lamp. A second lamp that produces UV-B is absolutely essential for the turtle to metabolize calcium properly. Direct, unfiltered sunlight is preferable. The lamps should be switched on during daylight hours.[10]

Diet

Pond plants such as elodea (anacharisan) and cabomba can also be left in the water, while human-consumed vegetables such as romaine lettuce, escarole and collard greens must be changed daily. As sliders are omnivores, insects and freshly killed fish may also be provided for protein. Commercially processed animal-based reptile food may be given too, but any sort of leftovers should be immediately removed to prevent fouling the water or turtle's habitat.[23]

Gallery

Trachemys scripta scripta in Francis Beidler Forest

Trachemys scripta scripta in Francis Beidler Forest Detail of head

Detail of head Detail of shell

Detail of shell Face

Face.jpg.webp) Upper part

Upper part.jpg.webp) Side view

Side view

See also

- Red-eared slider × yellow-bellied slider sometimes called yellow-eared slider

References

- ↑ NatureServe (5 May 2023). "Trachemys scripta scripta". NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer. Arlington, Virginia: NatureServe. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ↑ First described by Carl Peter Thunberg, and published in:

Ioannis Davidis Schoepff (1792). Historia Testudinum Iconibus Illustrata. Published in Erlangen, by Ioannis Iacobi Palm. p. 16-17. - ↑ Fritz Uwe; Peter Havaš (2007). "Checklist of Chelonians of the World". Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 207. doi:10.3897/vz.57.e30895. S2CID 87809001.

- ↑ Conant, R., J. Collins. 1991. Peterson Field Guides: Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern/Central North America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co.

- ↑ Scriber, K. T.; et al. (August 4, 1986). "Genetic Divergence among Populations of the Yellow-Bellied Slider Turtle (Pseudemys scripta) Separated by Aquatic and Terrestrial Habitats". Copeia. American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists. 1986 (3): 691–700. doi:10.2307/1444951. JSTOR 1444951.

- ↑ "Yellow-Bellied Slider reptiles". Reptile Channel. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

- ↑ Mo, Matthew (2019-04-01). "Possible records of Yellow-bellied Sliders (Trachemys scripta scripta) or River Cooters (Pseudemys concinna) in Hong Kong". Reptiles & Amphibians. 26 (1): 51–53. doi:10.17161/randa.v26i1.14337. ISSN 2332-4961. S2CID 241839429.

- ↑ "Care Sheet — Yellow-bellied Slider". Austin's Turtle Page. Retrieved 2008-10-23.

- ↑ "Yellow-bellied Slider Turtle". Savannah River Ecology Laboratory, University of Georgia. Retrieved 2014-02-13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Choosing a Yellow-Bellied Slider". Pet Place. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

- ↑ GIBBON, J. WHITFIELD, and JEFFREY E. LovICH. "On the slider turtle (Trachemys scripta)." Herpetological monographs 4 (1990): 1-29.

- ↑ Vamberger, M., Ihlow, F., Asztalos, M., Dawson, J., Jasinski, S., Praschag, P., & Fritz, U. (2019). So different, yet so alike: North American slider turtles (Trachemys scripta). Vertebrate Zoology, 70, 87-96.

- ↑ Scardino, Rita; Mazzoleni, Sofia; Rovatsos, Michail; Vecchioni, Luca; Dumas, Francesca (2020-06-25). "Molecular Cytogenetic Characterization of the Sicilian Endemic Pond Turtle Emys trinacris and the Yellow-Bellied Slider Trachemys scripta scripta (Testudines, Emydidae)". Genes. 11 (6): 702. doi:10.3390/genes11060702. ISSN 2073-4425. PMC 7348936. PMID 32630506.

- ↑ Mcgregor, Kelly Armentrout and Cari. "Trachemys scripta (pond slider, scripta)." Animal Diversity Web, University of Michigan, 2020.

- ↑ Ochoa, Julio (June 30, 2007). "Red-eared slider turtles now on state's no-no list for pets". Naples Daily News. Retrieved 2008-10-23.

- ↑ Armentrout, Kelly; Mcgregor, Cari. "Trachemys scripta (Pond Slider, scripta)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ↑ Morreale, Stephen J.; Gibbons, J. Whitfield; Congdon, Justin D. (1984-06-01). "Significance of activity and movement in the yellow-bellied slider turtle (Pseudemys scripta)". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 62 (6): 1038–1042. doi:10.1139/z84-148. ISSN 0008-4301.

- ↑ Morreale, Stephen J.; Gibbons, J. Whitfield (1986). "Habitat Suitability Index: Slider Turtle" (PDF). United States Fish and Wildlife Service.

- ↑ Bouchard, S. S. (2004). Diet selection in the yellow-bellied slider turtle, Trachemys scripta: ontogenetic diet shifts and associative effects between animal and plant diet items. University of Florida.

- ↑ Team, R. H. (2021, August 9). Yellow-bellied slider: Ultimate Guide. Reptile Handbook. Retrieved April 14, 2022, from https://reptilehandbook.com/yellow-bellied-slider-ultimate-guide/#:~:text=In%20the%20wild%2C%20the%20primary%20predators%20of%20the,the%20moment%20they%20feel%20threatened%20by%20a%20predator.

- ↑ "Yellow-bellied Slider". Savannah River Ecology Laboratory, University of Georgia. Retrieved 2014-06-08.

- ↑ Eskew, Evan A.; Price, Steven J.; Dorcas, Michael E. (2010-09-01). "Survival and recruitment of semi-aquatic turtles in an urbanized region". Urban Ecosystems. 13 (3): 365–374. doi:10.1007/s11252-010-0125-8. ISSN 1573-1642. S2CID 1893235.

- ↑ Bouchard, S. S., & Bjorndal, K. A. (2006). Ontogenetic Diet Shifts and Digestive Constraints in the Omnivorous Freshwater Turtle Trachemys scripta. Physiological & Biochemical Zoology, 79(1), 150–158. https://doi.org/10.1086/498190