| |

| Alternative names | Jodrell Bank Experimental Station |

|---|---|

| Named after | William Jauderell |

| Organization | |

| Location | Lower Withington, Cheshire East, Cheshire, North West England, England |

| Coordinates | 53°14′10″N 2°18′26″W / 53.23625°N 2.3071388888889°W |

| Altitude | 77 m (253 ft) |

| Established | 1945 |

| Website | www |

| Telescopes |

|

Location of Jodrell Bank Observatory | |

| | |

| Location | Cheshire, England |

| Criteria | Cultural: (i), (ii), (iv), (vi) |

| Reference | 1594 |

| Inscription | 2019 (43rd Session) |

| Area | 17.38 ha (42.9 acres) |

| Buffer zone | 18,569.22 ha (45,885.5 acres) |

Jodrell Bank Observatory (/ˈdʒɒdrəl/ JOD-rəl) in Cheshire, England, hosts a number of radio telescopes as part of the Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics at the University of Manchester. The observatory was established in 1945 by Bernard Lovell, a radio astronomer at the university, to investigate cosmic rays after his work on radar in the Second World War. It has since played an important role in the research of meteoroids, quasars, pulsars, masers and gravitational lenses, and was heavily involved with the tracking of space probes at the start of the Space Age.

The main telescope at the observatory is the Lovell Telescope. Its diameter of 250 ft (76 m) makes it the third largest steerable radio telescope in the world. There are three other active telescopes at the observatory; the Mark II, and 42 ft (13 m) and 7 m diameter radio telescopes. Jodrell Bank Observatory is the base of the Multi-Element Radio Linked Interferometer Network (MERLIN), a National Facility run by the University of Manchester on behalf of the Science and Technology Facilities Council.

The Jodrell Bank Visitor Centre and an arboretum are in Lower Withington, and the Lovell Telescope and the observatory near Goostrey and Holmes Chapel. The observatory is reached from the A535. The Crewe to Manchester Line passes by the site, and Goostrey station is a short distance away. In 2019, the observatory became a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[1][2]

Early years

Jodrell Bank was first used for academic purposes in 1939 when the University of Manchester's Department of Botany purchased three fields from the Leighs. It is named from a nearby rise in the ground, Jodrell Bank, which was named after William Jauderell, an archer whose descendants lived at the mansion that is now Terra Nova School. The site was extended in 1952 by the purchase of a farm from George Massey on which the Lovell Telescope was built.[3]

The site was first used for astrophysics in 1945, when Bernard Lovell used some equipment left over from World War II, including a gun laying radar, to investigate cosmic rays.[4] The equipment was a GL II radar system working at a wavelength of 4.2 m, provided by J. S. Hey.[5][6] He intended to use the equipment in Manchester, but electrical interference from the trams on Oxford Road prevented him from doing so. He moved the equipment to Jodrell Bank, 25 miles (40 km) south of the city, on 10 December 1945.[6][7] Lovell's main research was transient radio echoes, which he confirmed were from ionized meteor trails by October 1946.[8] The first staff were Alf Dean and Frank Foden who observed meteors with the naked eye while Lovell observed the electromagnetic signal using equipment.[9] The first time Lovell turned the radar on – 14 December 1945 – the Geminids meteor shower was at a maximum.[7]

Over the next few years, Lovell accumulated more ex-military radio hardware, including a portable cabin, known as a "Park Royal" in the military (see Park Royal Vehicles). The first permanent building was near to the cabin and was named after it.[8]

Jodrell Bank is primarily used for investigating radio waves from the planets and stars.

Searchlight telescope

A searchlight was loaned to Jodrell Bank in 1946 by the army;[10] a broadside array, was constructed on its mount by J. Clegg.[10] It consisted of 7 elements of Yagi–Uda antennas.[11] It was used for astronomical observations in October 1946.[12]

On 9 and 10 October 1946, the telescope observed ionisation in the atmosphere caused by meteors in the Giacobinids meteor shower. When the antenna was turned by 90 degrees at the maximum of the shower, the number of detections dropped to the background level, proving that the transient signals detected by radar were from meteors.[11] The telescope was then used to determine the radiant points for meteors. This was possible as the echo rate is at a minimum at the radiant point, and a maximum at 90 degrees to it.[10] The telescope and other receivers on the site studied the auroral streamers that were visible in early August 1947.[13][14]

Transit Telescope

The Transit Telescope was a 218 ft (66 m) parabolic reflector zenith telescope built in 1947. At the time, it was the world's largest radio telescope. It consisted of a wire mesh suspended from a ring of 24 ft (7.3 m) scaffold poles, which focussed radio signals on a focal point 126 ft (38 m) above the ground. The telescope mainly looked directly upwards, but the direction of the beam could be changed by small amounts by tilting the mast to change the position of the focal point. The focal mast was changed from timber to steel before construction was complete.[3]

The telescope was replaced by the steerable 250 ft (76 m) Lovell Telescope, and the Mark II telescope was subsequently built at the same location.

The telescope could map a ± 15-degree strip around the zenith at 72 and 160 MHz, with a resolution at 160 MHz of 1 degree.[15] It discovered radio noise from the Great Nebula in Andromeda – the first definite detection of an extragalactic radio source – and the remnants of Tycho's Supernova in the radio frequency; at the time it had not been discovered by optical astronomy.[16]

Lovell Telescope

The "Mark I" telescope, now known as the Lovell Telescope, was the world's largest steerable dish radio telescope, 76.2 metres (250 ft) in diameter, when it was constructed in 1957;[17] it is now the third largest, after the Green Bank telescope in West Virginia and the Effelsberg telescope in Germany.[18] Part of the gun turret mechanisms from the First World War battleships HMS Revenge and HMS Royal Sovereign were reused in the telescope's motor system.[19] The telescope became operational in mid-1957, in time for the launch of the Soviet Union's Sputnik 1, the world's first artificial satellite. The telescope was the only one able to track Sputnik's booster rocket by radar;[20][21] first locating it just before midnight on 12 October 1957, eight days after its launch.[22][23]

In the following years, the telescope tracked various space probes. Between 11 March and 12 June 1960, it tracked the United States' NASA-launched Pioneer 5 probe. The telescope sent commands to the probe, including those to separate it from its carrier rocket and turn on its more powerful transmitter when the probe was eight million miles away. It received data from the probe, the only telescope in the world capable of doing so.[24] In February 1966, Jodrell Bank was asked by the Soviet Union to track its unmanned Moon lander Luna 9 and recorded on its facsimile transmission of photographs from the Moon's surface. The photographs were sent to the British press and published before the Soviets made them public.[25]

In 1969, the Soviet Union's Luna 15 was also tracked. A recording of the moment when Jodrell Bank's scientists observed the mission was released on 3 July 2009.[26]

With the support of Sir Bernard Lovell, the telescope tracked Russian satellites. Satellite and space probe observations were shared with the US Department of Defense satellite tracking research and development activity at Project Space Track.

Tracking space probes only took a fraction of the Lovell telescope's observing time, and the remainder was used for scientific observations including using radar to measure the distance to the Moon and to Venus;[27][28] observations of astrophysical masers around star-forming regions and giant stars;[29] observations of pulsars (including the discovery of millisecond pulsars[30] and the first pulsar in a globular cluster);[31] and observations of quasars and gravitational lenses (including the detection of the first gravitational lens[32] and the first Einstein ring).[33] The telescope has also been used for SETI observations.[34]

Mark II and III telescopes

The Mark II telescope is an elliptical radio telescope, with a major axis of 38.1 metres (125 ft) and a minor axis of 25.4 metres (83 ft).[35] It was constructed in 1964. As well as operating as a standalone telescope, it has been used as an interferometer with the Lovell Telescope, and is now primarily used as part of the MERLIN project.[36][37] The Mark III telescope, the same size as the Mark II, was constructed to be transportable[38] but it was never moved from Wardle, near Nantwich, where it was used as part of MERLIN. It was built in 1966 and decommissioned in 1996.[39]

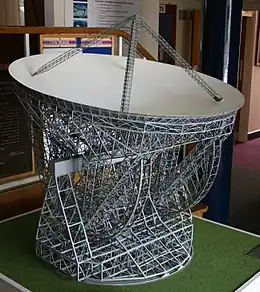

Mark IV, V and VA telescope proposals

The Mark IV, V and VA telescope proposals were put forward in the 1960s through to the 1980s to build even larger radio telescopes.

The Mark IV proposal was for a 1,000 feet (300 m) diameter standalone telescope, built as a national project.

The Mark V proposal was for a 400 feet (120 m) moveable telescope. The concept of this proposal was for a telescope on a 3⁄4-mile-long (1.2 km) railway line adjoining Jodrell Bank, but concerns about future levels of interference meant that a site in Wales would have been preferable. Design proposals by Husband and Co and Freeman Fox, who had designed the Parkes Observatory telescope in Australia, were put forward.

The Mark VA was similar to the Mark V but with a smaller dish of 375 feet (114 m) and a design using prestressed concrete, similar to the Mark II (the previous two designs more closely resembled the Lovell telescope).[40]

None of the proposed telescopes was constructed, although design studies were carried out and scale models were made, partly because of the changing political climate, and partly due to the financial constraints of astronomical research in the UK. Also it became necessary to upgrade the Lovell Telescope to the Mark IA, which overran in terms of cost.[40]

Other single dishes

A 50 ft (15 m) alt-azimuth dish was constructed in 1964 for astronomical research and to track the Zond 1, Zond 2, Ranger 6 and Ranger 7 space probes[41] and Apollo 11.[42] After an accident that irreparably damaged the 50 ft telescope's surface, it was demolished in 1982 and replaced with a more accurate telescope, the "42 ft". The 42 ft (12.8 m) dish is mainly used to observe pulsars, and continually monitors the Crab Pulsar.[43]

When the 42 ft was installed, a smaller dish, the "7 m" (actually 6.4 m, or 21 ft, in diameter) was installed and is used for undergraduate teaching. The 42 ft and 7 m telescopes were originally used at the Woomera Rocket Testing Range in South Australia.[44] The 7 m was originally constructed in 1970 by the Marconi Company.[45]

A Polar Axis telescope was built in 1962. It had a circular 50 ft (15.2 m) dish on a polar mount,[46] and was mostly used for moon radar experiments. It has been decommissioned. An 18-inch (460 mm) reflecting optical telescope was donated to the observatory in 1951[47] but was not used much, and was donated to the Salford Astronomical Society around 1971.[48]

MERLIN

The Multi-Element Radio Linked Interferometer Network (MERLIN) is an array of radio telescopes spread across England and the Welsh borders. The array is run from Jodrell Bank on behalf of the Science and Technology Facilities Council as a National Facility.[49] The array consists of up to seven radio telescopes and includes the Lovell Telescope, the Mark II, Cambridge, Defford, Knockin, Darnhall, and Pickmere (previously known as Tabley). The longest baseline is 217 kilometres (135 mi) and MERLIN can operate at frequencies between 151 MHz and 24 GHz.[39] At a wavelength of 6 cm (5 GHz frequency), MERLIN has a resolution of 50 milliarcseconds which is comparable to that of the HST at optical wavelengths.[49]

Very Long Baseline Interferometry

Jodrell Bank has been involved with Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI) since the late 1960s; the Lovell telescope took part in the first transatlantic interferometer experiment in 1968, with other telescopes at Algonquin and Penticton in Canada.[50] The Lovell Telescope and the Mark II telescopes are regularly used for VLBI with telescopes across Europe (the European VLBI Network), giving a resolution of around 0.001 arcseconds.[36]

Square Kilometre Array

In April 2011, Jodrell Bank was named as the location of the control centre for the planned Square Kilometre Array, or SKA Project Office (SPO).[51] The SKA is planned by a collaboration of 20 countries and when completed, is intended to be the most powerful radio telescope ever built. In April 2015 it was announced that Jodrell Bank would be the permanent home of the SKA headquarters[52] for the period of operation expected for the telescope (over 50 years[53]).

Research

The Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics, of which the Observatory is a part, is one of the largest astrophysics research groups in the UK.[54] About half of the research of the group is in the area of radio astronomy – including research into pulsars, the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation, gravitational lenses, active galaxies and astrophysical masers. The group also carries out research at different wavelengths, looking into star formation and evolution, planetary nebula and astrochemistry.[55]

The first director of Jodrell Bank was Bernard Lovell, who established the observatory in 1945. He was succeeded in 1980 by Sir Francis Graham-Smith, followed by Professor Rod Davies around 1990 and Professor Andrew Lyne in 1999.[56] Professor Phil Diamond took over the role on 1 October 2006, at the time when the Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics was formed. Prof Ralph Spencer was Acting Director during 2009 and 2010. In October 2010, Prof. Albert Zijlstra became Director of the Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics. Professor Lucio Piccirillo was the Director of the Observatory from Oct 2010 to Oct 2011. Prof. Simon Garrington is the JBCA Associate Director for the Jodrell Bank Observatory. In 2016, Prof. Michael Garrett was appointed as the inaugural Sir Bernard Lovell chair of Astrophysics and Director of Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics. As Director JBCA, Prof. Garrett also has overall responsibility for Jodrell Bank Observatory.

In May 2017 Jodrell Bank entered into a partnership with the Breakthrough Listen initiative and will share information with Jodrell Bank's team, who wish to conduct an independent SETI search via its 76-m radio telescope and e-MERLIN array.

There is an active development programme researching and constructing telescope receivers and instrumentation. The observatory has been involved in the construction of several Cosmic Microwave Background experiments, including the Tenerife Experiment, which ran from the 1980s to 2000, and the amplifiers and cryostats for the Very Small Array.[57] It has also constructed the front-end modules of the 30 and 44 GHz receivers for the Planck spacecraft.[58] Receivers were also designed at Jodrell Bank for the Parkes Telescope in Australia.[59]

Visitor facilities, and events

A visitors' centre, opened on 19 April 1971 by the Duke of Devonshire,[60] attracted around 120,000 visitors per year. It covered the history of Jodrell Bank and had a planetarium and 3D theatre hosting simulated trips to Mars. Asbestos in the visitors' centre buildings led to its demolition in 2003 leaving a remnant of its far end. A marquee was set up in its grounds while a new science centre was planned. The plans were shelved when Victoria University of Manchester and UMIST merged to become the University of Manchester in 2004, leaving the interim centre, which received around 70,000 visitors a year.[61]

In October 2010, work on a new visitor centre started and the Jodrell Bank Discovery Centre opened on 11 April 2011.[62] It includes an entrance building, the Planet Pavilion, a Space Pavilion for exhibitions and events, a glass-walled cafe with a view of the Lovell Telescope and an outdoor dining area, an education space, and landscaped gardens including the Galaxy Maze.[63] A large orrery was installed in 2013.[64] It does not, however, include a planetarium, though a small inflatable planetarium dome has been in use on the site in recent years.

The visitor centre is open Tuesday to Sunday and Mondays during school and bank holidays and organises public outreach events, including public lectures, star parties, and "ask an astronomer" sessions.[65]

A path around the Lovell telescope is approximately 20 m from the telescope's outer railway, information boards explain how the telescope works and the research that is done with it.

The 35 acres (140,000 m2) arboretum, created in 1972, houses the UK's national collections of crab apple Malus and mountain ash Sorbus species, and the Heather Society's Calluna collection. The arboretum also has a small scale model of the Solar System, the scale is approximately 1:5,000,000,000. At Jodrell Bank, as part of the SpacedOut project, is the Sun in a 1:15,000,000 scale model of the Solar System covering Britain.[66]

On 7 July 2010, it was announced that the observatory was being considered for the 2011 United Kingdom Tentative List for World Heritage Site status.[67] It was announced on 22 March 2011 that it was on the UK government's shortlist.[68] In January 2018, it became the UK's candidate for World Heritage status.[69]

In July 2011 the visitor centre and observatory hosted "Live from Jodrell Bank - Transmission 001" – a rock concert with bands including The Flaming Lips, British Sea Power, Wave Machines, OK GO and Alice Gold.[70] On 23 July 2012, Elbow performed live at the observatory and filmed a documentary of the event and the facility which was released as a live CD/DVD of the concert. On 6 July 2013, Transmission 4 featured Australian Pink Floyd, Hawkwind, The Time & Space Machine and The Lucid Dream.[71] On 7 July 2013, Transmission 5 featured New Order, Johnny Marr, The Whip, Public Service Broadcasting, Jake Evans and Hot Vestry.[72] On 30 August 2013, Transmission 6 featured Sigur Ros, Polca and Daughter.[73]

On 31 August 2013, Jodrell Bank hosted a concert performed by the Hallé Orchestra to commemorate what would have been Lovell's 100th birthday. As well as a number of operatic performances during the day, the evening Halle performance saw numbers such as themes from Star Trek, Star Wars and Doctor Who among others. The main Lovell telescope was rotated to face the onlooking crowd and used as a huge projection screen showing various animated planetary effects. During the interval the 'screen' was used to show a history of Lovell's work and Jodrell Bank.[74]

There is an astronomy podcast from the observatory, named The Jodcast.[75] The BBC television programme Stargazing Live is hosted in the control room of the observatory. The programme has had four series, in January 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2014.[76]

Since 2016, the observatory hosted Bluedot,[77] a music and science festival, featuring musical acts such as Public Service Broadcasting, The Chemical Brothers, as well as talks by scientists and scientific communicators such as Jim Al-Khalili and Richard Dawkins.

Threat of closure

On 3 March 2008, it was reported that Britain's Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC), faced with an £80 million shortfall in its budget, was considering withdrawing its planned £2.7 million annual funding of Jodrell Bank's e-MERLIN project. The project, which aimed to replace the microwave links between Jodrell Bank and a number of other radio telescopes with high-bandwidth fibre-optic cables, greatly increasing the sensitivity of observations, was seen as critical to the survival of the facility. Bernard Lovell said "It will be a disaster … The fate of the Jodrell Bank telescope is bound up with the fate of e-MERLIN. I don't think the establishment can survive if the e-MERLIN funding is cut".[78][79]

On 9 July 2008, it was reported that, following an independent review, STFC had reversed its initial position and would now guarantee funding of £2.5 million annually for three years.[80]

Fictional references

Jodrell Bank has been mentioned in several works of fiction, including Doctor Who (The Tenth Planet, Remembrance of the Daleks, "The Poison Sky", "The Eleventh Hour", "Spyfall") and Birthday Boy by David Baddiel. It was intended to be a filming location for Logopolis (Tom Baker's final Doctor Who serial) but budget restrictions prevented this and another location with a superimposed model of a radio telescope was used instead. It was also mentioned in The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy[81] (as well as The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy film), The Creeping Terror and Meteor.

Jodrell Bank was also featured heavily in the 1983 music video "Secret Messages" by Electric Light Orchestra and also "Are We Ourselves?" by The Fixx. The Prefab Sprout song Technique (from debut album Swoon) opens with the line "Her husband works at Jodrell Bank/He's home late in the morning".

The observatory is the site of several episodes in the novel Boneland by the local novelist Alan Garner (2012), and the central character, Colin Whisterfield, is an astrophysicist on its staff.

Appraisal

Since 13 July 1988 the Lovell Telescope has been designated as a Grade I listed building.[82] On 10 July 2017 the Mark II Telescope was also designated at the same grade.[83] On the same date five other buildings on the site were designated at Grade II; namely the Searchlight Telescope,[84] the Control Building,[85] the Park Royal Building,[86] the Electrical Workshop,[87] and the Link Hut.[88] Grade I is the highest of the three grades of listing, and is applied to buildings that are of "exceptional interest", and Grade II, the lowest grade, is applied to buildings "of special interest".[89]

At the 43rd Session of the UNESCO World Heritage Committee in Baku on 7 July 2019, the Jodrell Bank Observatory was adopted as a World Heritage Site on the basis of 4 criteria[90]

- Criterion (i): Jodrell Bank Observatory is a masterpiece of human creative genius related to its scientific and technical achievements.

- Criterion (ii): Jodrell Bank Observatory represents an important interchange of human values over a span of time and on a global scale on developments

- Criterion (iv): Jodrell Bank Observatory represents an outstanding example of a technological ensemble which illustrates a significant stage in human history

- Criterion (vi): Jodrell Bank Observatory is directly and tangibly associated with events and ideas of outstanding universal significance.

See also

References

- ↑ "Six cultural sites added to UNESCO's World Heritage List". UNESCO. 7 July 2019.

- ↑ "Jodrell Bank gains Unesco World Heritage status". BBC News. 7 July 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- 1 2 Lovell, The Story of Jodrell Bank

- ↑ Lovell, The Story of Jodrell Bank, p. 2

- ↑ Astronomer by Chance, p. 110

- 1 2 Gunn, 2005

- 1 2 Lovell, The Story of Jodrell Bank, p. 3

- 1 2 Lovell, The Story of Jodrell Bank, p. 9

- ↑ "Bernard Lovell". The Economist. 18 August 2012. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- 1 2 3 Lovell, The Story of Jodrell Bank, p. 10

- 1 2 Astronomer by Chance, p. 129

- ↑ Astronomer by Chance, p. 128

- ↑ Lovell, The Story of Jodrell Bank, p. 15

- ↑ Astronomer by Chance, p. 186

- ↑ Lovell, Bernard (1950). Blue Book. Archived from the original on 14 January 2010. (the proposal document for the Lovell Telescope). pp. 4–5

- ↑ "The Early History". Jodrell Bank Observatory. Archived from the original on 27 October 2008. Retrieved 22 November 2006.

- ↑ "On This Day—14 March 1960: Radio telescope makes space history". BBC News. 14 March 1960. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ↑ "The Lovell Telescope presents a new face to the Universe". 5 November 2002. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ↑ Lovell, The Story of Jodrell Bank, p. 29

- ↑ "Jodrell Bank's Cold War history". BBC News Channel. 20 May 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ↑ "The team that tracked Sputnik – and the world's first intercontinental ballistic missile". BBC. 4 October 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ↑ Lovell, The Story of Jodrell Bank, p. 196

- ↑ Lovell, Astronomer by Chance, p. 262

- ↑ Lovell, The Story of Jodrell Bank, p. xii, pp. 239–244

Lovell, Astronomer by Chance, p. 272

"Voice in Space". Time Magazine. 21 March 1960. Archived from the original on 1 April 2007. Retrieved 9 April 2007.

"Big Voice from Space". Time Magazine. 23 May 1960. Archived from the original on 21 April 2009. Retrieved 9 April 2007. - ↑ Lovell, The Story of Jodrell Bank, p. 250

"On This Day—3 February 1966: Soviets land probe on Moon". BBC News. 3 February 1966. Retrieved 9 April 2007.

"The Lunar Landscape". Time Magazine. 11 February 1966. Archived from the original on 20 February 2008. Retrieved 7 April 2007. - ↑ Brown, Jonathan (3 July 2009). "Recording tracks Russia's Moon gatecrash attempt". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 9 June 2022. Retrieved 16 July 2009., includes link to recording with Lovell

- ↑ Lovell, Out of the Zenith, pp. 197–198

- ↑ Lovell, Astronomer by Chance, pp. 277–280

- ↑ "Introduction to cosmic masers". Jodrell Bank Observatory. 28 January 2005. Retrieved 1 June 2007.

- ↑ "JBO—Stars". Jodrell Bank Observatory. Retrieved 1 June 2007.

- ↑ "Milestones". Jodrell Bank Observatory. Archived from the original on 28 October 2008. Retrieved 28 May 2007.

- ↑ Lovell, Astronomer by Chance, pp. 297–301

- ↑ "Astronomers see cosmic mirage". BBC News. 1 April 1998. Retrieved 9 April 2007.

- ↑ "Scientists listen intently for ET". BBC News. 1 February 1998. Retrieved 9 April 2007.

- ↑ "The MKII Radio Telescope". Jodrell Bank Observatory. Archived from the original on 27 October 2008. Retrieved 1 June 2007.

- 1 2 "The Merlin and VLBI National Facility". Jodrell Bank Observatory. Archived from the original on 1 May 2008. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ↑ "The quest for the resolving power". Jodrell Bank Observatory. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ↑ Palmer and Rowson (1968)

- 1 2 "MERLIN user guide—4.1 Location of Telescopes". Retrieved 5 August 2007.

- 1 2 Lovell, Jodrell Bank Telescopes

- ↑ "Jodrell Bank's role in early space tracking activities". Jodrell Bank Observatory. Archived from the original on 27 October 2008. Retrieved 10 June 2007.

- ↑ "The other space race: Transcript". BBC/Open University. Retrieved 14 June 2007.

- ↑ "Jodrell Bank—Pulsars". Jodrell Bank Observatory. Retrieved 10 June 2007.

- ↑ "JBO—Lovell Observing Room". Jodrell Bank Observatory. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 10 June 2007.

- ↑ "NRAL—7 m Telescope". Jodrell Bank Observatory. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

- ↑ Lovell, Jodrell Bank Telescopes, p. 232

- ↑ Pullan, A history of the University of Manchester 1951–73, p. 37

- ↑ "Salford Astronomical Society—Observatory". Salford Observatory. Archived from the original on 2 December 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2007.

- 1 2 "MERLIN/VLBI National Facility". Jodrell Bank Observatory. Retrieved 5 August 2007.

- ↑ Lovell, Out of the Zenith, pp. 67–68

- ↑ "Jodrell Bank to play key part in creating world's largest radio telescope". The Guardian. 3 April 2011. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ↑ "World's largest radio telescope has a permanent home for its headquarters – SKA Telescope". SKA Telescope. 30 April 2015. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ↑ "Information regarding the SKA Headquarters selection process – SKA Telescope". SKA Telescope. 11 March 2015. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ↑ "Research groups: School of Physics and Astronomy". The University of Manchester. Archived from the original on 18 August 2007. Retrieved 5 August 2007.

- ↑ "Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics Research". Jodrell Bank Observatory. Retrieved 5 August 2007.

- ↑ "Director of the Nuffield Radio Astronomy Laboratories, Jodrell Bank". Jodrell Bank Observatory. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2007.

- ↑ "JBO—VSA Receivers". Jodrell Bank Observatory. Retrieved 23 June 2007.

- ↑ "Jodrell Bank—Observing the Big Bang". Jodrell Bank Observatory. Retrieved 10 June 2007.

- ↑ "Jodrell Bank—Anatomy of a Radio Telescope". Jodrell Bank Observatory. Archived from the original on 16 October 2008. Retrieved 10 June 2007.

- ↑ Lovell, Out of the Zenith

- ↑ "Government 'stifling scientists'". PA News. 28 March 2008. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ↑ "Jodrell Bank unveils £3m discovery centre". BBC News. 7 April 2011. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ↑ "Jodrell Bank Discovery Centre is being redeveloped". Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- ↑ "Jodrell Bank Discovery Centre unveils 'world's biggest' orrery". BBC News. 26 March 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ "Visit – Jodrell Bank". Jodrell Bank Observatory. Archived from the original on 30 March 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ↑ "SpacedOut Location: The Sun at Jodrell Bank". SpacedOut. Archived from the original on 13 December 2005. Retrieved 8 June 2007.

- ↑ "Applicants for UK Tentative World Heritage Status". Department for Culture Media and Sport. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ↑ Kennedy, Maev (22 March 2011). "UK nominates 11 sites for Unesco world heritage status". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ↑ "Jodrell Bank selected as next UK nomination for UNESCO World Heritage Site status". The United Kingdom National Commission for UNESCO. 2018. Archived from the original on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- ↑ "Shows: Live from Jodrell Bank". Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ↑ "Support Acts Confirmed for The Australian Pink Floyd Jodrell Bank Show". 6 May 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ↑ "New Order – Live from Jodrell Bank". Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ↑ "Daughter, Polica & Sigur Ros @ Jodrell Bank – 30/08/2013". Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ↑ OFlynn, Elaine; Greer, Stuart (2 September 2013). "Pictures: Hallé Orchestra stars light up Jodrell Bank". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- ↑ "The Jodcast". Jodrell Bank Observatory. Retrieved 8 June 2007.

- ↑ "Stargazing Live: Behind the scenes at Jodrell Bank". BBC News. 9 January 2013. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ↑ "Travel". Bluedot Festival. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ↑ "Jodrell Bank fears funding loss". BBC News. 6 March 2008.

- ↑ Smith, Lewis; Coates, Sam (7 March 2008). "Professor Sir Bernard Lovell condemns 'disastrous' plan to close Jodrell Bank". The Times. London. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ↑ "Deal to rescue Jodrell Bank helps Britain see its future in the stars". The Times. 9 July 2008.

- ↑ Adams, Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, p. 30–31

- ↑ Historic England, "Jodrell Bank Observatory: Lovell Telescope (1221685)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 16 July 2017

- ↑ Historic England, "Jodrell Bank Observatory: Mark II Telescope (1443087)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 16 July 2017

- ↑ Historic England, "Jodrell Bank Observatory: 71MHz Searchlight Aerial (1443133)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 16 July 2017

- ↑ Historic England, "Jodrell Bank Observatory: Control Building (1443868)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 16 July 2017

- ↑ Historic England, "Jodrell Bank Observatory: Park Royal Building (1443093)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 16 July 2017

- ↑ Historic England, "Jodrell Bank Observatory: Electrical Workshop (Former Main Office) (1444238)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 16 July 2017

- ↑ Historic England, "Jodrell Bank Observatory: Link Hut (Cosmic Noise Hut) (1443486)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 16 July 2017

- ↑ What is Listing?, Historic England, retrieved 16 July 2017

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2019. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Books

- Adams, Douglas (1986). Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy—A Trilogy in Four Parts. Pan Books. ISBN 0-330-31611-7.

- Gunn, A. G. (2005). "Jodrell Bank and the Meteor Velocity Controversy". In The New Astronomy: Opening the Electromagnetic Window and Expanding Our View of Planet Earth, Volume 334 of the Astrophysics and Space Science Library. Part 3, pages 107–118. Springer Netherlands. doi:10.1007/1-4020-3724-4_7

- Lovell, Bernard (1968). Story of Jodrell Bank. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-217619-6.

- Lovell, Bernard (1973). Out of the Zenith: Jodrell Bank, 1957–70. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-217624-2.

- Lovell, Bernard (1985). The Jodrell Bank Telescopes. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-858178-5.

- Lovell, Bernard (1990). Astronomer by Chance. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-55195-8.

- Piper, Roger (1972) [1965]. The Story of Jodrell Bank (Carousel ed.). London: Carousel. ISBN 0-552-54028-5.

- Pullan, Brian; Abendstern, Michele (2000). A history of the University of Manchester 1951–1973. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-5670-5.

Journal articles

- Palmer, H. P.; B. Rowson (1968). "The Jodrell Bank Mark III Radio Telescope". Nature. 217 (5123): 21–22. Bibcode:1968Natur.217...21P. doi:10.1038/217021a0. S2CID 4282648.