59°17′32″N 11°5′0″E / 59.29222°N 11.08333°E

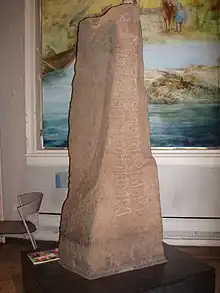

| Tune stone | |

|---|---|

| Tunesteinen | |

| |

| Writing | Elder Futhark |

| Created | 200–450 AD |

| Discovered | 1627 Tune, Østfold, Norway |

| Present location | Norwegian Museum of Cultural History, Oslo, Norway |

| Culture | Norse |

| Rundata ID | N KJ72 U |

| Runemaster | Wiwaz |

| Text – Native | |

| See article. | |

| Translation | |

| See article. | |

The Tune stone is an important runestone from about 200–450 AD. It bears runes of the Elder Futhark, and the language is Proto-Norse. It was discovered in 1627 in the church yard wall of the church in Tune, Østfold, Norway. Today it is housed in the Norwegian Museum of Cultural History in Oslo. The Tune stone is possibly the oldest Norwegian attestation of burial rites, inheritance, and beer.[1]

Inscription

The stone has inscriptions on two sides, called side A and side B. Side A consists of an inscription of two lines (A1 and A2), and side B consists of an inscription of three lines (B1, B2 and B3),[2] each line done in boustrophedon style.[3]

The A side reads:

- A1: ekwiwazafter·woduri

- A2: dewitadahalaiban:worathto·?[---

The B side reads:

- B1: ????zwoduride:staina:

- B2: þrijozdohtrizdalidun

- B3: arbijasijostezarbijano

The transcription of the runic text is:

- A: Ek Wiwaz after Woduride witandahlaiban worhto r[unoz].

- B: [Me]z(?) Woduride staina þrijoz dohtriz dalidun(?) arbija arjostez(?) arbijano.[4]

The English translation is:

- I, Wiwaz, made the runes after Woduridaz, my lord. For me, Woduridaz, three daughters, the most distinguished of the heirs, prepared the stone.[4]

The name Wiwaz means 'the promised one', from Proto-Indo-European *h₁wegʷʰ-ós, while Woduridaz means 'fury-rider'.[3] The phrase witandahlaiban, translated as 'my lord', literally means 'ward-bread' or 'guardian of the bread'.[5][6] (The English word lord similarly originates from Old English hlāford < hlāf-weard, literally 'loaf-ward', i.e. 'guardian of the bread'.)

Interpretations

The runic inscription was first interpreted by Sophus Bugge in 1903 and Carl Marstrander in 1930, but the full text was not interpreted convincingly until 1981 by Ottar Grønvik in his book Runene på Tunesteinen. A later interpretation was made by Terje Spurkland in 2001.[7]

Spurkland's translation differs somewhat from the translation given above, running:

- I, Vi, in memory of Vodurid, the bread lord, made runes

- I left Vodurid the stone. Three daughters prepared the burial ale, the most godborne of the heirs[7]

Grønvik and Marstrander also agree the three daughters prepared the burial ale, rather than the stone.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Online entry on the Tune stone in Store norske leksikon.

- ↑ Inscription provided from this site's entry on the Tune stone. Slightly adapted to fit Wikipedia.

- 1 2 Antonsen (2002:126–127)

- 1 2 Projektet Samnordisk runtextdatabas – Rundata

- ↑ Page (1987:31).

- ↑ Nielsen (2006:267).

- 1 2 Terje Spurkland. I begynnelsen var Futhark. Cappelen akademisk forlag, 2001.

References

- Antonsen, Elmer H. (2002). Runes and Germanic Linguistics. Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-017462-6.

- Grønvik, Ottar (1981). Runene på Tunesteinen: Alfabet, Språkform, Budskap. Universitetsforlaget ISBN 82-00-05656-2

- Nielsen, Hans Frede (2006). "The Early Runic Inscriptions and German Historical Linguistics". In Stoklund, Marie; Nielsen, Michael Lerche; et al. (eds.). Runes and Their Secrets: Studies in Runology. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 87-635-0428-6.

- Page, Raymond Ian (1987). Runes. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06114-4.