_by_Aert_Anthoniszoon.jpg.webp)

Until 1815 the Beylik of Tunis maintained a corsair navy to attack European shipping, raid coastal towns on the northern shores of the Mediterranean and defend against incursions from Algiers or Tripoli. After 1815 Tunis tried, with limited success, to create a modern navy, which fought in the Greek War of Independence and the Crimean War.

The corsair age

Corsairing was less important to the economy of Tunis than to the other Barbary States, but under Yusuf Dey in the early seventeenth century it grew in scale, and the capture of foreign ships became a key source of income for the ruler. Each time a ship was captured it went to the Bey as booty, together with half of its crew - the remainder being divided among the corsairs themselves.[1]

To be sustainable, corsair activity needed a significant investment in shipping, skilled people and scarce resources, and these were only intermittently available in Tunis. The selling of European captives back to their countries of origin and the purchase of ship hulls from foreign ports went on continuously, but at times when the profitability of agriculture or trade rose, corsair activity tended to decline, as, for example, during the periods 1660–1705 and 1760–1792.[2] Like Algiers and Tripoli, Tunis needed to import most of the materials necessary to build and maintain a fleet, including rope, tar, sails and anchors and the wood necessary to convert captured merchantmen into warships.[3]

The Beys of Tunis sent out their fleets on their own account, but also derived income by chartering part of their navy to privateers. The Ben Ayyed family chartered 36 percent of the Tunisian corsair fleet between 1764 and 1815 (making them the second largest), paying a tithe (uchur) for the privilege, but the profits they yielded were not significant.[2]

Shipbuilding and naval organisation

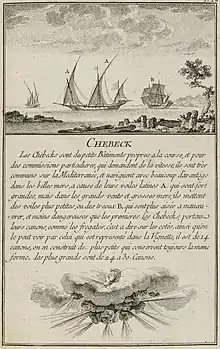

The Tunisian corsair fleet consisted mainly of xebecs and galiots, many of them converted merchant ships.[4][5] In the eighteenth century the European powers abandoned the galley[6] and began building larger ships of the line. While a xebec could carry up to 24 guns, European battleships commonly carried 74 guns after 1750.[7][8] It thus became increasingly difficult for Tunis to build, equip, man or maintain a naval force that could remain effective in the face of other modern navies in the Mediterranean. In the seventeenth century Tunis and the other Barbary states depended on Christian European craftsmen to build its ships and naval installations; this was less the case by the eighteenth century but the Tunisian navy always depended on imported finished goods. As Tunis sought to keep apace with the European fleets, it relied less on privateering and developed the infrastructure of a state navy.[9]

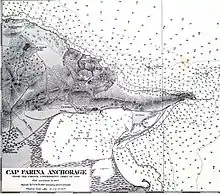

The main port for the corsair navy was Porto Farina, sixty kilometres north of Tunis. It offered shelter under Cape Farina from the northeast wind. It was slowly silting up as a result of the outflow of the Medjerda River, and eventually became unusable for larger ships.[10] Some galleys were maintained at Bizerte and there were also naval installations at La Goulette.[11] A naval arsenal was built in Porto Farina in 1707, but by 1769 the site seems to have been abandoned and the facility moved to La Goulette. The Venetians bombarded Porto Farina in 1784, but after this no foreign navy paid attention to it.[12]

Hammuda Pasha sought to increase Tunis’ naval autonomy by building modern naval shipyards at Porto Farina and La Goulette as well as a cannon foundry in Tunis, which employed Christian slave labour and used materials imported from Spain.[13] The harbour at La Goulette was exposed to enemy attack, so in 1818, fearing that Lord Exmouth would destroy his entire navy as he had the Algerian fleet, Mahmud Bey had the entrance to Porto Farina dredged clear do that he could move his ships back there, where they could shelter in the lagoon.[14]: 338 However, after the destruction of the Tunisian fleet in the storm of 1821, Porto Farina was effectively abandoned again.[12]

One of the noteworthy aspects of how the Tunisian navy was organised was that for many decades it was the charge of one man, Mohamed Khodja. He was originally appointed by Ali Bey in around 1780 as commander of the maritime fort of Bizerte. The commander of the ships themselves was first admiral Mustapha Raïs, and after 1825, Mohamed Sghaïer, and Hammuda Pasha soon appointed Mohamed Khodja as director of the naval arsenals (amin el-tarsikhana). After 1818 Mohamed Khodja had the task of reforming the Tunisian navy and reconverting the corsairs and their ships. He remained in post even after the defeat at Navarino, and served until his death in 1846 in a role which came to resemble that of a modern Minister of the Marine. One of his sons Ahmad, who predeceased him, was commander of Porto Farina while another, Mahmoud, succeeded him in his role as amin el-tarsikhaneh.[15]: 60

Treaties and conflict (1705–1805)

When the Husainid dynasty took power in Tunis in 1705, piracy and privateering had long been part of the country's economy.[14]: 121 Over time, various maritime countries signed treaties with Tunis, agreeing to make gifts and payments in return for security against attack and enslavement.[16][17] For example, the 1797 treaty with the United States assured a payment to Tunis of $107,000 in return for not attacking American shipping.[18]: 52 [14]: 236 An offer from Sweden in 1814 worth 75,000 piastres to the Bey, with regular payments every three years to secure the safety of its shipping was considered inadequate and not accepted.[14]: 296–7 In 1815, the Netherlands offered the Bey half a million francs in presents to ensure the free movement of its ships.[14]: 303

Having secured these subsidies with the threat of piracy, Tunis and the other Barbary states did not always adhere to their obligations, and at times they still seized shipping from countries with which they had treaties. In 1728 the French, in exasperation, decided that a show of force was necessary. On 19 July 1728 a naval force under Etienne Nicolas de Grandpré consisting of two ships of the line, three frigates, a flute, three bomb galiots and two galleys left Toulon.[19]: 206 [20] When this fleet appeared off La Goulette the Tunisian navy did not oppose it and the Bey quickly agreed to France's terms. (Tripoli refused them, and was bombarded for six days).[19]: 206

By the late eighteenth century the Tunisian fleet was no longer capable of posing a threat to the major European naval powers.[21] When a dispute over Corsican shipping and the rights to coral fishing in Tabarka led to the outbreak of war with France in June 1770, the Tunisian fleet did not attempt to engage the French navy, which was able to bombard Porto Farina, Bizerte and Sousse with impunity.[14]: 170–185 In 1784 a dispute with the Republic of Venice led to war; on 1 September a Venetian fleet of three ships of the line, a frigate, two xebecs and a galiot appeared off Tunis. Supported by two British frigates, this force sailed to Porto Farina, bombarding it repeatedly between 9–18 September. Sailing back, the Venetians then bombarded La Goulette from 30 October - 19 November. They returned in 1786, bombarding Sfax repeatedly from 18 March - 8 May, Bizerte in July and Sousse in September. In no case did any Tunisian fleet put to sea or offer resistance - the country relied entirely on shore batteries for defence.[14]: 200–215

If the Venetian bombardment showed that Tunis was no longer a major naval force, it could still pose a threat to its neighbours. Thus in 1799 a fleet of twelve corsairs under the command of Mohammed Rais Roumali raided San Pietro Island off Sardinia, carrying its entire population away into slavery.[14]: 237 [22]

The Barbary Wars and war with Algiers (1805–1815)

In 1804 Tunisian naval power consisted of one thirty-six gun frigate with another under construction, 32 xebecs with between 6 and 36 guns, thirty armed galleys and ten gunboats. That year Tunis attempted, unsuccessfully, to secure the delivery of another frigate from the United States as the price of maintaining the peace.[18]: 52 Hostilities were threatened during the First Barbary War when the USS Constitution seized a Tunisian corsair and its prizes that were attempting to run the US blockade of Tripoli. When the USS Vixen appeared off Tunis in July 1805, a Tunisian gunboat opened fire on her and gave chase. The Vixen continued on her way into port, and neither she nor Stephen Decatur, aboard the USS Congress, returned fire.[23] During the Second Barbary War the United States demanded compensation for two American vessels that had been seized by the British in the War of 1812 and held in Tunis as prizes. To secure peace, Tunis agreed to pay compensation, reversing thirty years of established practice whereby the USA maintained peace by paying the Barbary States.[24]

The Regency of Tunis fought a protracted conflict with the Regency of Algiers over many years, almost entirely on land. However, in May 1811 an Algerian fleet entered Tunisian waters and engaged a Tunisian force off Sousse. The Algerian squadron consisted of six large ships and four gunboats under the command of Raïs Hamidou; the Tunisian of twelve warships under Mohammed al-Mourali. Fighting was confined to the two flagships but after six hours of combat Mourali was compelled to strike his colours and surrender. The rest of the Tunisian fleet took shelter in Monastir while the Algerians sailed home with their prize. This was the first serious naval engagement the two regencies had ever fought, costing 230 Tunisian and 41 Algerian lives.[14]: 268 In 1812 the Algerians returned, and blockaded La Goulette with nineteen ships from 24 July to 10 August. Both sides were careful to avoid escalation, so neither opened fire on the other.[14]: 284–5

In August 1815 the Tunisian fleet made ready to face another incursion by the Algerians, An Algerian naval fleet attacked a Tunisian fleet but failed in front of a Tunisian fleet. Muhammad|Mahmud Bey]] dispatched eight Corsair ships under Moustafa Reis to pillage the coasts of Italy, hoping to amass both slaves and treasure. After several fruitless raids over six weeks, the fleet attacked Sant'Antioco in Sardinia, seizing 158 slaves before returning to La Goulette in October loaded with booty.[14]: 305–6 [22] This was the last major raid undertaken by the Tunisian fleet, and it was instrumental in bringing about an end to its historic activities.[25]

The end of the corsair age (1815–1821)

After the final defeat of Napoleon in Europe in 1815, the powers gathered at the Congress of Vienna to agree a new political order. One of the questions they considered was the slave trade and the continuing depredations of the Barbary corsairs. Sardinia in particular urged the powers to take decisive action to free the captives from Sant’Antioco and from previous raids, and to prevent any other attacks in future. To resolve these matters Britain dispatched a fleet to the Barbary states under Lord Exmouth, who carried authority to negotiate an end these practices from a number of European powers, including Great Britain, Hanover, Sardinia and Naples.[26][27]

Exmouth's force of eighteen warships appeared off La Goulette on 10 April 1816. The Tunisian fleet made no attempt to resist it.[28] Mahmud Bey agreed to Exmouth's terms, and a treaty was signed with the European powers on 17 April 1816.[29][30] As a result of Exmouth's expedition, 781 slaves and prisoners were redeemed from Tunis (along with 580 from Tripoli and 1514 from Algiers).[31]

In 1820 the Tunisian navy had three 48-gun frigates, and this sizeable force was deployed to attack Algiers, which had violated its peace agreement by attacking Tunisian shipping. The Tunisian navy set off to make a show of force off Algiers at the end of October, and did manoeuvre between Algiers and the Balearic Islands, but based itself in Livorno to be safe against any counterattack. Towards the end of December it returned to La Goulette, having exhausted its supplies.[14]: 341

It remained at La Goulette when a huge storm blew up on 7–9 February 1821, driving 21 ships aground in the Gulf of Tunis and damaging many others.[22]: 418 Among the ships lost were the Bey's three frigates, together with three corvettes, a brig, a schooner and a xebec. This loss had serious consequences for Tunis, leaving it unable to prosecute the war with Algiers and destroying the naval superiority it then enjoyed with its neighbour. Tunis therefore agreed to accept the Sublime Porte’s offer of mediation, and signed a peace agreement with Algiers in March. It also left Tunis unable to provide immediate naval assistance to the Ottomans in the Greek War of Independence.[22]: 419 [32][14]: 342–4

Defeat at Navarino (1821–1837)

As well as destroying ships, the storm of 1821 also carried away all their crews - around two thousand seamen with the skills and experience to sail them. To maintain a first-rate navy, Tunis could not rely on locally-built ships and needed to purchase vessels from the leading European naval yards. In March 1821 Mahmud Bey sent Mourali and other agents to Marseilles, Trieste and Venice to see whether any warships could be purchased, as well as to Istanbul to recruit new experienced crews.[22]: 419 [32]

To replace the ships lost, two frigates, the Hassaniya and the Mansoura,[32] two corvettes and a brig were ordered from the shipyards at Marseilles while three vessels were purchased at La Goulette. As soon as they were delivered, the frigates were sent to support the Ottomans in Greece.[22]: 420

In March 1827 Sultan Mahmud II requested additional Tunisian naval support in Greece. Husayn Bey responded by sending a flotilla to the Morea that consisted of two frigates, two corvettes and two brigs.[22]: 420 (A different account says two frigates and one brig).[33]: vii–viii [34]: 143 In October 1827 the Tunisian ships were surprised along with the rest of the Ottoman navy and completely destroyed at the Battle of Navarino, leaving Tunis obliged to rebuild its navy from scratch for a second time in six years. In May 1828 two new brigantines had been built at La Goulette - these remained the only effective warships in Tunis until 1830. When the Ottoman government made a fresh request for warships in 1829, the Bey declined to send them. These ships were insufficient force prevent the Kingdom of Sardinia and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies from blockading Tunis in 1833, forcing the Bey to sign a favourable commercial treaty. As before, Tunis did not want to risk losing its warships by giving battle.[22]: 420–421

The defeat at Navarino prompted Husayn Bey to decide that his warships needed to fly under a distinctive flag so as to distinguish themselves from other squadrons in the Ottoman fleet. This was the origin of the flag that later became the national flag of Tunisia. The flag was officially adopted in 1831.[35][36]

Tunisian forces played no part in the conflict between France and Algiers between 1827 and 1830;[37] indeed the losses from Navarino were not fully replaced until 1834 when a 44-gun frigate and two corvettes were commissioned in Marseilles. The order was for ships with flat bottoms which could safely enter the harbour at La Goulette, which was sanding up.[22]: 429 The first of the new frigates was launched on 3 November and named Husayniyya.[33]: 54 By this time the French conquest of Algeria had prompted the Ottomans to re-occupy Tripoli and consider invading Tunis as well.[37]: 127–8

Ahmed Bey and the Crimea (1837–1855)

An 1839 French consular report lists the Tunisian navy as comprising:[34]: 144

- one 44-gun frigate (disarmed)

- two 24-gun corvettes

- two 22-gun corvettes (disarmed)

- one 20-gun corvette (disarmed)

- one 16-gun brig (disarmed)

- one 10-gun schooner (in dry dock)

- two large gunboats (disarmed)

- twelve smaller single-gun gunboats (disarmed)

- two small single-gun cutters (disarmed)

By 1840 all of the world's major navies had built or were building large steam-powered warships.[33]: v Tunisia's first steamship was bought in 1841 but unfortunately sank in less than a year. The Dante, a 160-ton steamship was presented by the French government to Ahmed Bey in 1846 after it took him to France on his state visit. Unfortunately the Dante ran aground in a storm off La Marsa and had to be decommissioned. Around a year later France replaced it with a second vessel the Minos, in 1848. It remained stationed in Tunisia under a French captain until the death of Ahmed Bey; his successor Mohammed Bey requested its withdrawal as an economy measure.[34]: 301 [38]

In the meantime Tunis was building and purchasing other ships to strengthen its naval capacity. Work began building a new frigate, the Ahmadiya in La Goulette in 1841. The channel connecting the basin with the sea was not wide enough to accommodate a ship of its size, but the Bey was convinced that it could be modified once the warship was built. The ship was launched on 2 January 1853 but remained marooned in the pool for years, unable to sail out because the widening had not been undertaken. Eventually it was broken up, having never reached the sea.[34]: 302 [38]

Ahmed Bey also bought craft such as the aviso Essed and the frigate Sadikia as well as other modern ships, the Béchir and Mansour. The Bey's plan was for this fleet to be based in Porto Farina where new port installations had been built. However, the silting up of the harbor of Porto Farina by the Medjerda River prevented this project from coming to fruition.[39]

Following the death of Mohamed Khodja in 1846, Ahmed Bey appointed his son fr:Mahmoud Khodja to succeed him as Minister of the Marine. In 1853 he brought engineers from France and Italy to rebuild the arsenal at La Goulette arsenal as well as various coastal forts.[15]: 102 In the same year the Ottoman government expressed surprise that the Bey of Tunis, as a loyal subject, had not offered to assist against Russia on the event of war. The Bey responded that he was ready to assist, possibly because a show of loyalty to the Ottomans would undermine the French policy of treating Tunis as independent when pressing its own demands. Mahmoud Khodja was responsible for chartering more than sixty ships to transport the 14,000 Tunisian troops who were sent to support Turkey. They mostly served in the garrison at Batum where their numbers were thinned by epidemics.[37]: 217–222

Hayreddin Pasha and the French invasion (1857–1881)

In 1857 Muhammad Bey reorganised his government along modern ministerial lines and following the death of a Mahmoud Khodja made Hayreddin Pasha Minister of the Marine, a post he occupied until 1862. The ministry figured in Tunisia's first ever national budget, for 1860–61. The amount allocated, 754,000 piastres, was only half of what Hayreddin had requested as necessary to keep the navy fed and supplied. During the time he was minister the Tunisian navy consisted of two frigates, five old steamships and ten sailing ships of various sizes. They were all in a poor state of repair and in October 1862 only one frigate was capable of leaving port. It was useless as a military force and its main activity was transporting livestock to keep the troops in the south supplied with meat, but in March 1862 the fleet was in such poor condition that the government had to charter foreign ships for the task. Hayreddin's main purpose was to modernise and fit out the port of La Goulette so that it could serve as a safe winter port for the fleet; as it could no longer accommodate ships of any size, the navy was obliged to shelter in the roads off Sfax.[38]

After Hayreddin Pasha Tunis had Navy Ministers who served only brief terms, Ismail Kahia (1862-3), General Rashid (1862-5), Mohammed Khaznadar (1865–72), Mustapha Ben Ismaïl (1873-76) and finally, on the eve of the French occupation, Ahmed Zarrouk (1876–81). In 1877, at the outbreak of the Russo-Turkish War, the Ottoman government asked Tunisia for assistance once again, but Tunisia did not have the financial means to assist.[40]

During the French invasion of Tunisia in 1881, the Tunisian navy offered no opposition.[41]

See also

- Sforza, Arturo. “LA RICOSTRUZIONE DELLA FLOTTA DA GUERRA DI TUNISI (1821-1836).” Africa: Rivista Trimestrale Di Studi e Documentazione Dell’Istituto Italiano per l’Africa e l’Oriente, vol. 42, no. 3, 1987, pp. 417–436. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40760173. Accessed 10 Apr. 2021

References

- ↑ Kevin Shillington (2013-07-04). Encyclopedia of African History 3-Volume Set. Routledge. p. 219. ISBN 978-1-135-45669-6.

- 1 2 Boubaker, Sadok (2003). "Trade and Personal Wealth Accumulation in Tunis from the Seventeenth to the Early Nineteenth Centuries". Revue d'histoire moderne et contemporaine. 50 (4): 29–62. doi:10.3917/rhmc.504.0029. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ↑ Michael Russell (1835). History and Present Condition of the Barbary States: Comprehending a View of Their Civil Institutions, Antiquities, Arts, Religion, Literature, Commerce, Agriculture, and Natural Productions. Oliver & Boyd. p. 404.

- ↑ United States Naval Academy (1981-04-01). New aspects of naval history: selected papers presented at the Fourth Naval History Symposium, United States Naval Academy, 25-26 October 1979. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 9780870214950.

- ↑ James Hingston Tuckey (1815). Maritime geography and statistics, or A description of the ocean and its coasts, maritime commerce, navigation, &c.

- ↑ Antonicelli, Aldo (4 May 2016). "From Galleys to Square Riggers: The modernization of the navy of the Kingdom of Sardinia". The Mariner's Mirror. 102 (2): 153. doi:10.1080/00253359.2016.1167396. S2CID 111844482.

- ↑ "oxfordreference.com". Oxford Reference. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ↑ David Steel (1812). The Elements and Practice of Naval Architecture; Or: A Treatise on Ship-building, Theoretical and Practical, on the Best Principles Established in Great Britain. With Copious Tables of Dimensions, &c. Illustrated with a Series of Thirty-nine Large Draughts, ... Steel and Company. p. 176.

- ↑ Clark, G.N. (1944). "The Barbary Corsairs in the Seventeenth Century". The Cambridge Historical Journal. 8 (1): 27, 34. doi:10.1017/S1474691300000561. JSTOR 3020800.

- ↑ Friedrich Rühs; Samuel Heinrich Spiker (1814). Zeitschrift für die neueste Geschichte die Staaten- und Völkerkunde. p. 136.

- ↑ The Little Sea Torch: Or True Guide for Coasting Pilots: by Which They are Clearly Instructed how to Navigate Along the Coasts of England, Ireland ... and Sicily. Debrett. 1801. p. 110.

- 1 2 Molinier, J. "Porto Farina" (PDF). mash.univ-aix.fr. Bulletin Economique et Social de la Tunisie. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ↑ Jean Batou (1990). Cent ans de résistance au sous-développement: l'industrialisation de l'Amerique latine et du Moyen-Orient face au défi européen, 1770–1870. Librairie Droz. p. 147. ISBN 978-2-600-04290-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Rousseau, Alphonse (1864). Annales tunisiennes, ou, Aperçu historique sur la régence de Tunis. Algiers: Bastide Libraire-Éditeur. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- 1 2 Ibn Abi Dhiaf (1990). Présent des hommes de notre temps. Chroniques des rois de Tunis et du pacte fondamental, vol. VIII. Tunis: Maison tunisienne de l'édition.

- ↑ Windler, Christian (March 2001). "Diplomatic History as a Field for Cultural Analysis: Muslim-Christian Relations in Tunis, 1700–1840". The Historical Journal. 44 (1): 79–106. doi:10.1017/S0018246X01001674. JSTOR 3133662. S2CID 162271552.

- ↑ Woodward, G. Thomas (September 2004). "The Costs of State–Sponsored Terrorism: The Example of the Barbary Pirates" (PDF). National Tax Journal. 57 (3): 599–611. doi:10.17310/ntj.2004.3.07. JSTOR 41790233. S2CID 153152236.

- 1 2 Spencer Tucker (2013-12-15). Stephen Decatur: A Life Most Bold and Daring. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-61251-510-6.

- 1 2 Paul Chack (2001). Marins à bataille. Le gerfaut. ISBN 978-2-901196-92-1.

- ↑ Alfred Graincourt (1780). Les hommes illustres de la marine française, leurs actions mémorables et leurs portraits. Jorry. p. 243.

- ↑ "Great Britain and the Barbary States in the Eighteenth Century". Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research. 29 (79): 87. May 1956. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2281.1956.tb02346.x. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Sforza, Arturo (September 1987). "La Ricostruzione della Flotta da Guerra di Tunisi (1821–1836)". Africa: Rivista trimestrale di studi e documentazione dell'Istituto italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente. 42 (3): 418. JSTOR 40760173.

- ↑ Robert J. Allison (2007). Stephen Decatur: American Naval Hero, 1779–1820. Univ of Massachusetts Press. pp. 72–3. ISBN 978-1-55849-583-8.

- ↑ Frank Lambert (2007-01-09). The Barbary Wars: American Independence in the Atlantic World. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-374-70727-9.

- ↑ Daniel Panzac (2005). The Barbary Corsairs: The End of a Legend, 1800-1820. BRILL. p. 273. ISBN 90-04-12594-9.

- ↑ Patricia Lorcin (2 October 2017). The Southern Shores of the Mediterranean and its Networks: Knowledge, Trade, Culture and People. Taylor & Francis. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-317-39426-6.

- ↑ Martti Koskenniemi; Walter Rech; Manuel Jiménez Fonseca (2017). International Law and Empire: Historical Explorations. Oxford University Press. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-19-879557-5.

- ↑ Julia A. Clancy-Smith (4 November 2010). Mediterraneans: North Africa and Europe in an Age of Migration, c. 1800–1900. University of California Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-520-94774-0.

- ↑ Charles F. Partington (1836). The British Cyclopaedia of Literature, History, Geography, Law and Politics. p. 781.

- ↑ The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British India and Its Dependencies. Black, Parbury, & Allen. 1816. p. 613.

- ↑ Brian E. Vick (13 October 2014). The Congress of Vienna. Harvard University Press. p. 390. ISBN 978-0-674-72971-1.

- 1 2 3 Buonocore, Ferdinando (June 1968). "DUE TRAGICI AVVENIMENTI NELLA REGGENZA DI TUNISI ALL'INIZIO DEL XIX SECOLO: Visti attraverso il carteggio del Consolato delle Due Sicilie conservato nell'Archivio di Stato di Napoli". Africa: Rivista trimestrale di studi e documentazione dell'Istituto italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente. 23 (2): 183–190. JSTOR 40757811.

- 1 2 3 Haughton, John (2012). The Navies of the World 1835–1840. Melbourne: Inkifingus. ISBN 978-0-646-57760-9. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 Leon Carl Brown (2015-03-08). The Tunisia of Ahmad Bey, 1837–1855. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-4784-6.

- ↑ Harbaoui, Zouhour (3 June 2018). "Une Modernité Tunisienne 1830–1930 (Première partie): Souvenirs du passé pour prévenir l'avenir…". Le Temps. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ↑ Bourial, Hatem (20 October 2016). "Le drapeau tunisien a 189 ans : Une étoile et un croissant dans un disque blanc…". Tunis Webdo. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- 1 2 3 Raymond, André (October 1953). "Introduction" (PDF). British Policy Towards Tunis (1830–1881) (PhD). St. Anthony’s College, Oxford. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- 1 2 3 G. S. van Krieken (1976). Khayr al-Dîn et la Tunisie: 1850–1881. Brill Archive. pp. 30–36. ISBN 90-04-04568-6.

- ↑ Bourial, Hatem (9 March 2017). "" Dante ", Minos ", Mansour " : la marine d'Ahmed Bey en 1846". webdo.tn. Tunis Webdo. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ↑ Arnoulet, François (1988). "Les rapports tuniso-ottomans de 1848 à 1881 d'après les documents diplomatiques". Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerranée. 47: 143–152. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ↑ Operations of the French Navy during the recent war with Tunis. U.S. Office of naval intelligence] Information from abroad. [War series, no. 1. HathiTrust Digital Library. 1883. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help)