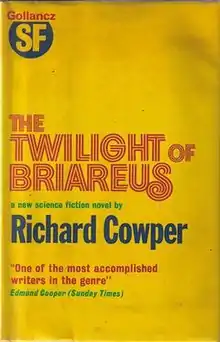

Original cover | |

| Author | "Richard Cowper" (John Middleton Murry Jr.) |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Science fiction novel |

| Publisher | Gollancz |

Publication date | 1974 |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 255 |

| OCLC | 948614 |

The Twilight of Briareus is a science-fiction novel by John Middleton Murry Jr., under his pseudonym Richard Cowper. It "combine[s] disaster and invasion themes".[1] One critic sees it as the book that Cowper's other novels resemble at heart.[2]

Writing and publication

According to Cowper, he wrote the book almost immediately after his novel Kuldesak was published successfully in 1970, and Twilight was "a more substantial work in every way". His publishers rejected it, and despite his discouragement he started the novel Clone with the idea of satirising science-fiction people who didn't like Twilight. His publishers accepted it and it sold well, after which they accepted Twilight, which sold even better.[3]

Setting and narration

The story takes place from 1983 to 1999, mostly in England. It begins in an apparently fictitious coastal town called Hampton and goes to other places such as Oxford and Geneva, ending at a farm in Lincolnshire.

The star Briareus Delta that figures in the story is also fictitious; there is no constellation called Briareus (a giant in Greek mythology).

The majority of the book is a first-person account written by the protagonist, Calvin Johnson. It begins with a scene of his finding the Lincolnshire farm and continues with a long flashback told in chronological order up to that point. This narration is followed by his diary at the farm. The book ends with a "postscript" by its editor, another character.

Summary

Briareus Delta becomes a supernova only about 130 light-years from Earth. While admiring the aurora it produces, the comprehensive-school English teacher Calvin Johnson meets one of his students, Margaret Hardy. Dazed after a tornado caused by the supernova, Calvin and Margaret are mysteriously compelled into a joyless sex act. Calvin learns that Margaret and many other sixteen-year-old girls then slept around the clock and longer, with strange dreams.

A few months later, it appears that no human pregnancies have started since the supernova. Calvin and others face the possibility of the extinction of humanity. Although most scientists are baffled, the retired zoology professor Angus McHarty speculates that some powerful entities have made use of the supernova to try to "take over" humanity, and conceptions are not occurring because at a deep level people prefer extinction to losing human identity.

The people who slept, mostly girls, are becoming known as "Zeta mutants" after a new "zeta" rhythm observable in their brainwaves. Sometimes their minds "meld" together, and they can have visions, which seem to be precognitive. They tend to accept events as they come—"the pattern must fulfill itself." At least some of the girls among them feel compelled to have sex with Calvin, but he resists. Researchers begin taking Zetas into custody because it appears that they can become pregnant, but Calvin, despite his connection with the Zetas, escapes with help from their sympathisers. It transpires that the Zeta research project produced no viable babies, and most of the subjects were killed or suffered mental damage. A remorseful world begins to treat the remaining Zetas well.

Calvin proves to be a "diplodeviant", one of very few people whose zeta and alpha rhythms are in phase. McHarty suggests that the Zetas have largely joined the take-over by the "Briarians" and that the diplodeviants, who are less fatalistic than most Zetas, have the deciding vote in whether humanity as a whole will accept it.

Calvin meets Margaret again and they become lovers. The children conceived just before the supernova, the "Twilight Generation", prove to be Zetas who share feelings and clairvoyant visions even more strongly than their elders. Most of them are brought to a centre in Geneva that is run along humanitarian lines. The supernova has disrupted the Gulf Stream and Britain's climate is becoming frigid, causing most of its inhabitants to leave. Calvin and Margaret move to Geneva for a few years.

Calvin and Margaret have visions of a certain farm in England, which they feel they have to find. After an arduous trip to Lincolnshire (where the snow is not quite yet melting in June), they find the farm in the possession of a teen-aged orphan, Elizabeth, and her cousin, Tony. Elizabeth is perhaps the only Twilighter who is the child of a Zeta; Calvin reaches the conclusion that she is also the only female diplodeviant. Tony and Margaret fall in love, and then Calvin and Elizabeth do likewise. To Calvin's astonishment, Elizabeth becomes pregnant. Spencer, a mystically and religiously inclined Zeta who had lived at the farm, returns to it.

Calvin has increasingly explicit visions and then conversations with the "Briarians". He learns that he is called upon to choose: the old humanity with its struggles, or the group consciousness and blissful life offered by the Briarians. Spencer compares Calvin's role to Christ's.

Spencer's postscript tells how, as Elizabeth is in labour, feral dogs attack the farm. Calvin takes a shotgun to deal with them, and it fires, killing him. Spencer concludes that Calvin intentionally sacrificed his life, as he knew this action was the only one both old humanity and the Zetas and Briarians could accept. The baby is born. At this moment, Zetas become able to conceive, and the world's rebirth begins, guided by the spiritual powers of the new generation.

Criticism

The Twilight of Briareus placed tenth in the poll for the Locus Award for science-fiction novels of 1974.[4]

Stephen E. Andrews and Nick Rennison omitted it from their list of "100 must-read science-fiction novels", but in his foreword, Christopher Priest said that it or Cowper's Road to Corlay "ought to be" there.[5]

Eden Robinson praised "the breadth of Cowper's imagination, the delicacy of his characterizations, the unpredictability of his plot" in this book. "I thought it was the coolest book I'd ever read, and since then, I haven't read many science fiction books that equal the originality of Twilight's dark vision."[6]

The Oxford Companion to Twentieth-Century Literature in English called it "perhaps his best novel" and grouped it as "one of his elegiac science fiction portraits of a fragile England threatened by transcendental change".[7]

Brian Stableford classified it with J. G. Ballard's early novels, Greybeard by Brian W. Aldiss (another book in which human reproduction stops), and The Furies by Keith Roberts, as part of the "more clinical and cynical phase" of "British 'cosy catastrophe' stories" that followed The Day of the Triffids and other thrillers.[8]

Neil Barron compared its science to that of The Inferno, by Fred and Geoffrey Hoyle. He said that its themes are similar to those of Childhood's End by Arthur C. Clarke, but it "lacks clarity about human transcendence."[9] Richard Bleiler, however, saw it as "sharpening" the message of Childhood's End by saying that humanity may need help rather than triumphing.[2]

References

- ↑ Nicholls, Peter; Clute, John (1979). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction: An Illustrated A to Z: Part 2. Granada. p. 173. ISBN 0-246-11020-1.

- 1 2 Bleiler, Richard (1999). Science Fiction Writers: Critical Studies of the Major Authors From the Early Nineteenth Century to the Present Day. Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 225–226. ISBN 0-684-80593-6.

- ↑ Elliott, Jeffrey M. (May 1981). "Interview: Richard Cowper". Fantasy Newsletter (36).

- ↑ von Ruff, Al (1995–2011). "1975 Locus Poll Award". Internet Science Fiction Database. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ↑ Priest, Christopher (2006). "Foreword". In Andrews, Stephen E.; Rennison, Nick (eds.). 100 Must-Read Science Fiction Novels. A. & C. Black. p. vi. ISBN 0-7136-7585-3. Cowper and Robert Sheckley were the only authors not in the book who Priest would have added.

- ↑ Robinson, Eden (30 March 2011). "The Twilight of Briareus—Richard Cowper". In Ondaatje, Michael; Redhill, Michael; Spalding, Esta; Spalding, Linda (eds.). Lost Classics. Anchor Books. pp. 189–190. ISBN 978-0-385-72086-1. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ↑ Stringer, Jenny, ed. (1996). The Oxford Companion to Twentieth-Century Literature in English. Oxford University Press. p. 145. ISBN 0-19-212271-1. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ↑ Stableford, Brian M. (2006). Science Fact and Science Fiction: An Encyclopedia. CRC Press. p. 131. ISBN 0-415-97460-7. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ↑ Barron, Neil (1981). Anatomy of Wonder: A Critical Guide to Science Fiction. Bowker. p. 183. ISBN 0-8352-1339-0.