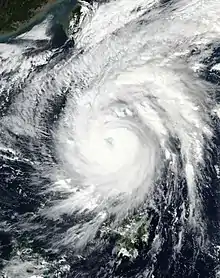

Vamco approaching landfall in Vietnam on November 14 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | November 8, 2020 |

| Dissipated | November 15, 2020 |

| Very strong typhoon | |

| 10-minute sustained (JMA) | |

| Highest winds | 155 km/h (100 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 955 hPa (mbar); 28.20 inHg |

| Category 4-equivalent typhoon | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/JTWC) | |

| Highest winds | 215 km/h (130 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 945 hPa (mbar); 27.91 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 102 total |

| Missing | 10 |

| Damage | $1.06 billion (2020 USD) |

| Areas affected | Philippines, Vietnam, Laos, Thailand |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 2020 Pacific typhoon season | |

Typhoon Vamco, known in the Philippines as Typhoon Ulysses, was a powerful and very destructive Category 4-equivalent typhoon that struck the Philippines and Vietnam. It also caused the worst flooding in Metro Manila since Typhoon Ketsana in 2009. The twenty-second named storm and tenth typhoon of the 2020 Pacific typhoon season, Vamco originated as a tropical depression northwest of Palau, where it slowly continued its northwest track until it made landfall in Quezon. After entering the South China Sea, Vamco further intensified in the South China Sea until it made its last landfall in Vietnam.

Vamco made its first landfall in the Philippines near midnight on November 11 in the Quezon province as a Category 2-equivalent typhoon. The typhoon brought heavy rains to Central Luzon and nearby provinces, including Metro Manila, the national capital. As the typhoon crossed the country, dams from all around Luzon neared their spilling points, forcing dam operators to release large amounts of water into their impounds. As the Magat Dam approached its spilling point, all seven of its gates were opened to prevent dam failure, which overflowed the Cagayan River and caused widespread floods in Cagayan and Isabela. After entering the South China Sea, Vamco further intensified until it reached its brief peak as a Category 4-equivalent typhoon. On November 15, Vamco made landfall in Vietnam as a Category 1-equivalent typhoon before dissipating shortly after.

Days after the typhoon had passed the Philippines, rescue operations in the Cagayan Valley were still ongoing due to the unexpected extent of the flooding. In response to the typhoon's effects, the entire landmass of Luzon was placed under a state of calamity. As of December 2, the Philippines' National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council had stated that the typhoon had 112 casualties (including 102 validated deaths, and another 10 missing), and the damages caused by Vamco reached ₱20.2 billion (US$1.06 billion).[1]

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

On November 8, the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) began tracking a new tropical depression 132 nautical miles (245 km; 150 mi) north-northwest of Palau.[2][3] At 12:00 UTC on the same day, the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) declared the system as a tropical depression inside of the Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR), prompting the agency to identify it as Ulysses.[4][5] The next day at 7:15 UTC, the system strengthened into a tropical storm, prompting JMA to identify the system as Vamco,[6] with the Joint Typhoon Warning Center later issuing their first warning on the system as a tropical depression. As the system tracked closer to southern Luzon, both the PAGASA and the JMA upgraded Vamco into a severe tropical storm.[7] Vamco was then upgraded to typhoon status by the JMA on November 11, followed by the JTWC and the PAGASA shortly after.[8][9] At 22:30 PHT (14:30 UTC) on November 11, Vamco made its first landfall on the island town of Patnanungan, Quezon.[10] Then, surrounded by favorable conditions for an intensification, Vamco continued to gain strength and reached its initial peak of intensity, with 10-min sustained winds at 130 km/h (81 mph), 1-minute sustained winds of 185 km/h (115 mph) and pressure of 970 mbar, supporting Vamco as a Category 3-equivalent typhoon.[11] At 23:20 PHT (15:20 UTC) and at 1:40 PHT of the following day (17:40 UTC), Vamco made its next two Quezon landfalls over Burdeos (in Polillo Island) and General Nakar (in the Luzon landmass), respectively.[12] Later, Vamco dropped below typhoon intensity inland. At 00:00 UTC, Vamco emerged over the South China Sea.[13] The system left the PAR at 01:30 UTC as the PAGASA redeclared the system as a typhoon.[14] Vamco gradually intensified in the South China Sea, before rapidly intensifying into its peak as a Category 4-equivalent typhoon on November 13.[15] The typhoon then weakened before making its last landfall in Vietnam as a Category 1-equivalent typhoon on November 15.[16] Shortly after, the typhoon weakened further into a tropical storm until it dissipated north of Laos.

Preparations

Philippines

As Vamco initially formed inside of the Philippine Area of Responsibility, the PAGASA immediately began issuing severe weather bulletins in preparation for the typhoon.[17] The Philippines had recently been hit with three other tropical cyclones — Typhoon Molave (Quinta), Typhoon Goni (Rolly), and Tropical Storm Etau (Tonyo) — making this the fourth tropical cyclone to approach Luzon in the past month. After Goni damaged the PAGASA's Doppler weather radar station in Catanduanes, one of the only three stations in the country, typhoon tracking was done manually.[18] The PAGASA first raised tropical cyclone wind signals as early as November 9.[19] By 23:00 UTC on November 10, the PAGASA had raised a Signal #2 wind signal for 17 provinces, parts of 6 provinces, 2 islands, and the national capital region, Metro Manila.[20] The National Disaster Risk Reduction Management Council (NDRRMC), also began sending out emergency alerts to mobile phone users about possible storm surges. The NDRRMC later used this same system to alert citizens in areas under Signal #3.[21]

Residents in the Pollilo Islands and in Central Luzon were forced to evacuate a day before the storm's landfall.[22][23] 14,000 residents were also to be evacuated in Camarines Norte.[24] Bicol Region, one of the regions worst hit by Goni last month, evacuated 12,812 individuals ahead of the incoming storm.[25] Over 2,071 passengers were stranded in ports in multiple regions of Luzon as sea conditions worsened.[26] Philippine Airlines suspended flights due to the inclement weather brought by Vamco.[27] The Office of the President of the Philippines suspended work in government offices and online classes in public schools in 7 regions, including the National Capital Region.[28] 12 hours before the typhoon's landfall, the PAGASA raised Signal #3 warnings for areas to be hit by the typhoon on landfall including Metro Manila and the entirety of Central Luzon.[9] The Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology then issued lahar warnings for the Mayon Volcano, the Taal Volcano, and Mount Pinatubo hours prior to the typhoon's landfall.[29] Prior to the typhoon's landfall, at least 231,312 individuals were evacuated by local government units.[1]

Vamco struck while the Philippines was in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, and various sections of the country were under different community quarantines.[30]

Vietnam

On November 14, at least 460,000 people were ordered to evacuate from the coastal areas by the government.[31] On the morning of that same day, all flights in five airports, including Da Nang, Chu Lai, Phu Bai, Dong Hoi and Vinh were ordered to be suspended or delayed.[32]

Impact

Vamco impacted the Philippines and Vietnam just a few days after the strike of Typhoon Goni. Both countries were still attempting to recover from Goni's initial impact, but Vamco went on to quickly exceed Goni's record as the sixth-costliest Philippine typhoon on record; in total both typhoons caused ₱37.2 billion (US$770 million) in damage in the Philippines alone.

Philippines

| Rank | Storm | Season | Damage | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHP | USD | ||||

| 2 | Yolanda (Haiyan) | 2013 | ₱95.5 billion | $2.2 billion | [33] |

| 3 | Odette (Rai) | 2021 | ₱51.8 billion | $1.02 billion | [34] |

| 3 | Pablo (Bopha) | 2012 | ₱43.2 billion | $1.06 billion | [35] |

| 4 | Glenda (Rammasun) | 2014 | ₱38.6 billion | $771 million | [36] |

| 5 | Ompong (Mangkhut) | 2018 | ₱33.9 billion | $627 million | [37] |

| 6 | Pepeng (Parma) | 2009 | ₱27.3 billion | $581 million | [38] |

| 7 | Ulysses (Vamco) | 2020 | ₱20.2 billion | $418 million | [39] |

| 8 | Rolly (Goni) | 2020 | ₱20 billion | $369 million | [40] |

| 9 | Paeng (Nalgae) | 2022 | ₱17.6 billion | $321 million | [41] |

| 10 | Pedring (Nesat) | 2011 | ₱15.6 billion | $356 million | [35] |

Even before the typhoon's landfall, Catanduanes had already experienced heavy rains, causing floods and rockslides in the province. Flood waters were reported to reach the roofs of some houses in Bagamanoc.[42]

Several areas in Luzon, including Metro Manila, reported that they experienced power outages prior to the typhoon making landfall.[43][44] The Philippine Stock Exchange was closed on November 12 due to the typhoon.[45]

Emergency hotlines in some locations became unavailable because most emergency numbers provided by national agencies and local governments were landline phone numbers, which were difficult to call from mobile phones, and became totally inaccessible once telephone lines in the localities were brought down by the storm.[46] The PAGASA's own phone lines went down due to technical problems on the morning of November 12, going back up a few hours later.[47] Broadcast news coverage had been significantly reduced compared to typhoons in previous years as a result of the shutdown of the ABS-CBN broadcast network, which had local news bureaus and strong signal reach in provinces far from Manila. The shutdown caused an information gap among areas which could only receive the network's signals.[48][49] Social media filled in some of the information gap, with some residents and even local governments treating it as a de facto emergency hotline.[50][51]

In the early hours of November 12, local government officials began reporting that their local rescue capabilities were already overwhelmed, and that they needed help from the national government in the form of airlift support and help from the Philippine Coast Guard.[52] After attending an online ASEAN summit that morning, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte addressed the nation via a pre-taped broadcast on state-owned television network People's Television Network (PTV), saying that he wanted to visit the storm-hit constituencies, but that he was constrained by his security personnel and doctor from doing so because of the risk to his safety and health.[53][54] Actor Jericho Rosales and digital creative Kim Jones resorted to using their surfboards to rescue stranded citizens in Marikina.[55] 52 national roads in 7 regions were damaged due to the typhoon's effects.[56]

As of January 13, 2021, the NDRRMC reported 98 deaths and 19 missing caused by Vamco. Economic loss in infrastructure were at ₱12.9 billion (US$267 million) while damage to agriculture reached ₱7.32 billion (US$151 million). Total damage across the country stood at ₱20.2 billion (US$418 million).[1] The Cagayan Valley experienced the highest total amount of damage. At least 5,184,824 individuals were affected by the typhoon's onslaught.[1] The Armed Forces of the Philippines and Philippine National Police reportedly rescued 265,339 and 104,850 individuals, respectively.[57][58] Contrary to the NDRRMC's report, Marikina officials report an unofficial damage of ₱40 billion (US$824 million).[59]

River floods

_of_Typhoon_Vamco_(2020)_in_Calumpit%252C_Bulacan_31.jpg.webp)

The Marikina River surpassed the water levels reached by Typhoon Ketsana in 2009, which brought massive rainfall and caused severe flooding. By 11:00 PHT on November 12, the river's water level had risen to 22 metres (72 ft), submerging most parts of the city in flood waters, according to the Marikina Public Information Office.[60] Marikina Mayor Marcelino Teodoro declared the city under a state of calamity due the massive floods brought by the typhoon.[61] Government scientists and advocacy sector conservationists warned that the flooding on the Marikina River was a consequence of the severe deforestation of the Upper Marikina River Watershed in Rizal province, where illegal logging, illegal quarrying, and landgrabbing continued to be a problem.[62][63][64]

In Pampanga, 86 villages experienced flooding due to the swelling of the Pampanga River.[65]

Dam overflow

Dams in the affected areas, including La Mesa Dam, Angat Dam, Binga Dam, Magat Dam, Ipo Dam, and Caliraya Dam, reached their maximum levels on November 12, forcing them to begin releasing water.[66][67][68]

By November 13, a water level of 192.7 metres (632 ft), 0.3 meters below the dam's spilling point, forced the Magat Dam to continue releasing water. All seven gates of the dam were opened at 24 meters as the dam released over 5,037 cubic metres (1,331,000 US gal) of water into the Cagayan River as numerous riverside towns experienced massive flooding.[69][70] Local governments continuously conducted rescue operations in their areas but had run out of equipment and manpower to rescue. Because there was very little media coverage of the flooding in the area, residents resorted to social media to request the national government for rescue.[71] Waters under the Buntun Bridge went up as high as 13 meters, flooding the nearby barangays up to the roofs of houses.[72][73] Rescue efforts continued into the early hours of November 14, but low visibility made aerial rescue efforts impossible until daylight.[74] Cagayan and Isabela have since declared a state of calamity.[1]

Following the severe flooding in the Cagayan Valley, experts called the valley the most flood-prone area in the country. The flood was caused by rain dumped by Typhoon Ulysses. The National Irrigation Administration was criticized for releasing water from the Magat Dam, which allegedly made the situation worse.[75]

Vietnam

Vamco began affecting Central Vietnam around midnight ICT on November 15. Although the storm was weaker already, a weather station on Lý Sơn island still reported hourly sustained winds of 100 km/h (62 mph) and gusts of up to 115 km/h (71 mph).[76] Strong winds downed many trees and damaged numerous homes in the four provinces from Hà Tĩnh to Thừa Thiên Huế.[76] In Thuận An, Thừa Thiên Huế, strong waves lashed docked fishing ships and civilian houses.[77] In the city of Da Nang, the storm surge destroyed many sea embankments, while washing rocks and debris onshore and into the streets.[77] Power outages affected 411,252 people in six central provinces.[78] A person was killed in Thừa Thiên-Huế Province, and economic loss in Quảng Bình Province reached 450 billion đồng (US$19.4 million).[79][80]

Aftermath

Philippines

Even after the typhoon had passed, widespread flooding from the typhoon's rains and from nearly overflowed dams wreaked havoc on the country days after its landfall.[81] Despite causing heavy floods, according to the PAGASA, Vamco released less rain that Typhoon Ketsana, another typhoon in 2009 which caused similar floods.[82] In response to the typhoon's effects, the entire landmass of Luzon was placed under a state of calamity.[83]

Public reactions to government response

Tuguegarao Mayor Jefferson Soriano drew criticism after a photo on social media showed him celebrating his birthday in Batangas while Tuguegarao was inundated by floods. Soriano regretted the trip, and stated that he underestimated the effects of the typhoon as no storm signals have were raised when he left for Batangas. Soriano attempted to return to Tuguegarao on November 12, a day after the typhoon's first landfall, however the North Luzon Expressway had already been blocked due to the typhoon.[84] He has been ordered to explain his absence to the Department of the Interior and Local Government, according to the department spokesman.[85][86]

Online discussion sparked regarding the Congress of the Philippines' budget cuts of ₱4 billion (US$83 million) to the NDRRMC during deliberations on the 2020 national budget, along with the closure of Project NOAH, a disaster prevention and mitigation tool, in 2017 by the Department of Science and Technology, citing the lack of funds.[87] Vice President Leni Robredo called for investigations after suspected oversights in disaster preparedness. Robredo stated that estimates on the possibility of flooding should be provided when a dam's gates are opened for public awareness.[84] The House of Representatives of the Philippines has since filed for a probe into the circumstances which led to the severe flooding in Cagayan and Isabela.[88]

Citizens on social media demanded accountability from the government, along with President Rodrigo Duterte, who had not made any appearance to the public during the typhoon's onslaught.[89] Presidential Spokesperson Harry Roque later defended the president's whereabouts, citing that the president "is always on top of things."[90][91][92] Roque denied shortcomings in preparation, however admitted that authorities "did not expect the gravity of the amount of water that descended on the lowlands." Roque also blamed multiple factors for the flooding, including climate change, deforestation, and illegal mining. Duterte also defended local government units in their disaster response measures.[93]

As a result of the shutdown of the ABS-CBN broadcast network, an information gap was formed among remote areas which could only receive the network's signals. This was raised by citizens on social media, and by Robredo as well.[48][49] Roque has since denied the existence of this gap.[88]

In a televised briefing for the typhoon, Duterte made sex jokes on-air with other government executives, to the dismay of the public. Gabriela Women's Party representative Arlene Brosas criticized Duterte's audacity to make "inappropriate jokes when people literally drowned and died due to the series of calamities," and that the citizens needed an "effective leadership and a concrete plan." Roque defended Duterte's comments, saying that he was trying to "lighten the mood" after witnessing multiple consecutive tragedies and that the jokes were Duterte's way of coping with disasters.[94][95][96]

Effects on education

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Department of Education (DepEd) required that classes be conducted through "modular learning", which involved the use of both online resources and printed self-learning materials dubbed "modules" for classes in public schools. While citizens evacuated from flooded areas, some students reported losing their modules due to the flood waters.[97] DepEd Secretary Leonor Briones was heavily criticized for saying that schools should solve the problem of damaged modules on their own by drying the modules with the sun or a flat iron. The DepEd later stated that they will replace the damaged modules through additional funds provided by its central office.[98]

In the aftermath of the typhoon, beginning November 15, some universities in the Philippines, including the Ateneo de Manila University, De La Salle University, Polytechnic University of the Philippines, and University of Santo Tomas, eased the academic workload for their students.[99] Synchronous sessions through online videoconferencing were temporarily suspended, and deadlines for requirements were moved to succeeding weeks.

The Pasig government suspended classes from preschool to senior high school in both public and private schools for November 16 and 17. Quezon City officials also declared the suspension of online classes from kinder to senior high school on the same days.[100] Marikina, after experiencing massive floods across the entire city, suspended classes in all levels until December 16.[101]

Retirement

During the season, the PAGASA announced that they retired the name Ulysses from its naming lists due to its significant impacts in Central and Southern Luzon and it will never be used again for another name within the Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR); It was replaced by Upang for the 2024 season.[102][103][104]

After the season, the Typhoon Committee announced that the name Vamco would be removed from the naming lists. In 2022, Bang-Lang was selected as the replacement for Vamco.[105][106][107]

See also

- Other tropical cyclones named Vamco

- Other tropical cyclones named Ulysses

- Weather of 2020

- Tropical cyclones in 2020

- Typhoon Patsy (1970) – Notable late-season typhoon that took a similar track in November 1970

- Typhoon Xangsane (2006) – Devastated Metro Manila and also had a similar wind strength to Vamco

- Typhoon Ketsana (2009)

- Typhoon Conson (2010) – A deadly Category 1 typhoon that took a similar track

- Typhoon Nari (2013) – A powerful typhoon which struck Central Luzon area and also had a similar destructive wind strength

- Tropical Storm Fung-wong (2014) – Similar situation to Ketsana and Vamco

- Typhoon Kammuri (2019) – impacted the Philippines at a similar time of year and caused widespread damage

- Typhoon Noru (2022) - A Category 5 typhoon that also struck the same areas as Vamco, caused widespread agricultural damage.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jalad, Ricardo B. (January 13, 2021). "SitRep no. 29 re Preparedness Measures and Effects for TY ULYSSES" (PDF). ndrrmc.gov.ph. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ↑ "Weather Maps". Japan Meteorological Agency. November 8, 2020. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- ↑ "Significant Tropical Weather Advisory for the Western and South Pacific Oceans". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. November 8, 2020. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 8, 2020. Alt URL

- ↑ Lalu, Gabriel Pabico (November 12, 2020). "Eye of Ulysses may move within 100 km north of Metro Manila an hour earlier". INQUIRER.net. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ "Severe Weather Bulletin #1 for Tropical Depression 'Ulysses'" (PDF). PAGASA. November 8, 2020. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 8, 2020. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- ↑ "Tropical Cyclone Information". Japan Meteorological Agency. November 8, 2020. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- ↑ "Severe Weather Bulletin #8 for Severe Tropical Storm 'Ulysses' (Vamco)" (PDF). PAGASA. November 10, 2020. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 8, 2020. Retrieved November 10, 2020. Alt URL

- ↑ Typhoon 25W (Vamco) Warning No. 7 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. November 11, 2020. Archived from the original on November 15, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020. Alt URL

- 1 2 "Severe Weather Bulletin #13 for Typhoon 'Ulysses' (Vamco)" (PDF). PAGASA. November 11, 2020. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 8, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020. Alt URL

- ↑ "Severe Weather Bulletin #17 for Typhoon 'Ulysses' (Vamco)" (PDF). PAGASA. November 11, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ↑ Typhoon 25W (Vamco) Warning No. 11 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. November 11, 2020. Archived from the original on November 15, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020. Alt URL

- ↑ "Severe Weather Bulletin #18 for Typhoon 'Ulysses' (Vamco)" (PDF). PAGASA. November 11, 2020. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 8, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020. Alt URL

- ↑ "Severe Weather Bulletin #21 for Typhoon 'Ulysses' (Vamco)" (PDF). PAGASA. November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ "Severe Weather Bulletin #26-FINAL for Typhoon 'Ulysses' (Vamco)" (PDF). PAGASA. November 13, 2020. Retrieved November 13, 2020.

- ↑ Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 25W (Vamco) Warning No. 18 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. November 13, 2020. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 13, 2020. Alt URL

- ↑ Typhoon 25W (Vamco) Warning No. 25 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. November 15, 2020. Archived from the original on November 15, 2020. Retrieved November 15, 2020. Alt URL

- ↑ "Low pressure area east of Mindanao now tropical depression Ulysses". ABS-CBN News. November 8, 2020. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ "WATCH: Ulysses being monitored manually in Catanduanes after Rolly damaged weather tools". GMA News Online. November 11, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ "Severe Weather Bulletin #4 for Tropical Storm 'Ulysses' (Vamco)" (PDF). PAGASA. November 10, 2020. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- ↑ "Severe Weather Bulletin #11 for Severe Tropical Storm 'Ulysses' (Vamco)" (PDF). PAGASA. November 10, 2020. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- ↑ Malasig, Jeline (November 11, 2020). "NDRRMC's text alerts (with warning tone) for threats of 'Ulysses' gets local Twitter talking anew". Interaksyon. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ "Local Authorities evacuate thousands as Typhoon 'Ulysses' approaches". interaksyon.philstar.com. Interaksyon Philippine Star. November 11, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ "Forced evacuation starts as C. Luzon braces for 'Ulysses'". www.pna.gov.ph. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ "14,000 families to be evacuated in Camarines Norte amid Ulysses' threat". GMA News Online. November 11, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ "OCD V says over 3,000 families preemptively evacuated in Bicol". GMA News Online. November 11, 2020. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ "Over 2K stranded in ports due to Typhoon Ulysses". www.pna.gov.ph. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ "PAL cancels several international, domestic flights due to 'Ulysses'". GMA News Online. November 11, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ "Palace suspends gov't work and classes today, tomorrow due to 'Ulysses'". Manila Bulletin. November 11, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ "Lahar warning raised in the wake of typhoon Ulysses". Manila Bulletin. November 11, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ "Coronavirus blocks 9 mayors from leading during Ulysses". Rappler. November 13, 2020. Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- ↑ Associated Press Hanoi (November 14, 2020). "Vietnam orders 460,000 to evacuate ahead of Typhoon Vamco". The Guardian. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- ↑ "Cục Hàng không 'lệnh' đóng cửa 5 sân bay vì bão số 13". Vietnam Finance (in Vietnamese). November 14, 2020. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- ↑ del Rosario, Eduardo D. (April 2014). FINAL REPORT Effects of Typhoon YOLANDA (HAIYAN) (PDF) (Report). NDRRMC. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- ↑ SitRep No. 44 for Typhoon ODETTE (2021) (PDF) (Report). NDRRMC. February 7, 2022. Retrieved February 15, 2022.

- 1 2 Uy, Leo Jaymar G.; Pilar, Lourdes O. (February 8, 2018). "Natural disaster damage at P374B in 2006-2015". Business World. Retrieved February 8, 2018 – via PressReader.

- ↑ Ramos, Benito T. (September 16, 2014). FINAL REPORT re Effects of Typhoon (PDF) (Report). NDRRMC. Retrieved September 17, 2014.

- ↑ Jalad, Ricardo B. (October 5, 2018). Situational Report No.55 re Preparedness Measures for TY OMPONG (I.N. MANGKHUT) (PDF) (Technical report). NDRRMC. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ↑ Rabonza, Glenn J. (October 20, 2009). FINAL Report on Tropical Storm \"ONDOY\" {KETSANA} and Typhoon \"PEPENG\ (PDF) (Report). NDRRMC. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ↑ Jalad, Ricardo B. (January 13, 2021). SitRep no. 29 re Preparedness Measures and Effects for TY ULYSSES (PDF). ndrrmc.gov.ph (Report). Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ↑ Jalad, Ricardo B. (November 10, 2020). "SitRep No.11 re Preparedness Measures for Super Typhoon Rolly" (PDF). NDRRMC. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- ↑ Jalad, Ricardo B. (July 29, 2023). "SitRep No.11 re Preparedness Measures for Severe Tropical Storm Paeng". NDRRMC.

- ↑ "Ulysses triggers flood, rockslide in Catanduanes". GMA News Online. November 11, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ "Power outages reported in Marikina City, Parts of Batangas, other areas". gmanetwork.com. GMA News. November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ Casinas, Jhon Aldrin (November 12, 2020). "Some Areas in Pasig experience power interruption as Ulysses Brings strong winds, heavy rain in Metro Manila". mb.com.ph. Manila Bulletin. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ Clarissa Batino, Cecilia Yap (November 11, 2020). "Philippine Markets Shut as New Storm Slams into Luzon, Killing 1". bloomberg.com. Bloomberg. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ Juan, Ratziel San. "'Cannot be reached': Emergency landline hotlines 'inaccessible' during Typhoon Ulysses". Philstar.com. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ Malasig, Jeline (November 12, 2020). "PAGASA's weather forecasting hotlines down due to technical issues". Interaksyon. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- 1 2 Marquez, Consuelo (November 14, 2020). "After ABS-CBN shutdown, lack of Ulysses warning made Cagayan residents suffer– Robredo". INQUIRER.net. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- 1 2 "ABS-CBN's Wide Reach Missed by Netizens as Typhoon Ulysses Hits Philippines". www.msn.com. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- ↑ "Social media becomes emergency helpline at the height of Typhoon 'Ulysses'". Manila Bulletin. November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ "As rescue calls pour in, OCD says it prepared enough for Ulysses". Rappler. November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ↑ "Marikina Mayor Teodoro: Nao-overwhelm na kami, parang Ondoy na ito". GMA News Online. November 12, 2020. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ "Duterte defends absence during Typhoon Ulysses onslaught, says he was told to prioritize his safety". cnn. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ Cabato, Regine. "Typhoon Vamco batters the Philippines, leaving millions without power". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ "Jericho Rosales, Kim Jones rescue typhoon victims using surfboards". Manila Bulletin. November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ "52 nat'l roads in 7 regions damaged due to 'Ulysses'". www.pna.gov.ph. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ↑ de Guzman, Robie (November 16, 2020). "Over 265k residents rescued by gov't troops in Ulysses-hit areas — AFP". UNTV. Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- ↑ "Thousands rescued by AFP, PNP from 'Ulysses' wrath". Manila Bulletin. November 13, 2020. Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- ↑ "Marikina to sue Angat Dam for floods higher than what Ondoy caused". GMA News Online. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- ↑ "Marikina River reaches 'Ondoy'-like water level". Manila Bulletin. November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ "Marikina under state of calamity "Mayor"". INQUIRER.net. November 13, 2020. Retrieved November 13, 2020.

- ↑ Enano, Jhesset O. (November 13, 2020). "Typhoon Ulysses: Less rain than Ondoy". Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- ↑ Manahan, Job (November 13, 2020). "Environmentalist: Diminished Marikina Watershed's condition similar to 'Stage 4 cancer'". ABS CBN News and Public Affairs. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- ↑ Limos, Mario Alvaro. "Gina Lopez Warned About Denuded Watersheds. Now, We're Paying the Price". Esquire Philippines. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- ↑ "Flooding in Pampanga feared to worsen as river swells after Ulysses". INQUIRER.net. November 14, 2020. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- ↑ "La Mesa Dam hits spilling level". Rappler. November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ Reyes-Estrope, Carmela (November 12, 2020). "Elevation in 3 Bulacan dams breaches spilling level due to Ulysses". INQUIRER.net. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ Marquez, Consuelo (November 12, 2020). "3 Luzon dams release water – Pagasa". INQUIRER.net. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ↑ "Residents near Ipo, Ambuklao, Binga, and Magat dams warned of flooding as reservoirs continue to release water". Manila Bulletin. November 13, 2020. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- ↑ "Typhoon Ulysses, monsoon rains spawn massive floods in Cagayan province". ABS-CBN News. November 13, 2020. Retrieved November 13, 2020.

- ↑ "CagayanNeedsHelp: Netizens' appeal for help goes viral on social media". Manila Bulletin.

- ↑ Lalu, Gabriel Pabico (November 13, 2020). "Robredo assures Cagayan Valley: We heard you, gov't finding ways to reach you". INQUIRER.net. Retrieved November 13, 2020.

- ↑ "Cagayan province turned into 'Pacific Ocean': disaster management official". ABS-CBN News. November 13, 2020. Retrieved November 13, 2020.

- ↑ Lalu, Gabriel Pabico (November 14, 2020). "Robredo discusses Cagayan rescue with military, but aerial response may be out". Retrieved November 13, 2020.

- ↑ "Severe flooding shows Cagayan Valley environmental risks". Inquirer News. November 18, 2020. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- 1 2 Mai Hương (November 15, 2020). "Bão số 13 đổ bộ, miền Trung thiệt hại nặng nề" (in Vietnamese).

- 1 2 Đức Nghĩa- Quang Nhật- Quang Luật (November 15, 2020). "Bão số 13 vào miền Trung: Bờ biển tan hoang, nhà tốc mái, cây gãy la liệt" (in Vietnamese).

- ↑ ANH TUẤN- QUANG HẢI (November 15, 2020). "Ngổn ngang" vì bão số 13" (in Vietnamese).

- ↑ "Thiệt hại do bão số 13: 1 người chết, hơn 1.500 nhà dân bị sập đổ, hư hỏng" (in Vietnamese). Báo Kinh Tế Đô Thị. November 15, 2020. Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- ↑ "Ước tổng giá trị thiệt hại ban đầu do bão số 13 gây ra là 450 tỷ đồng" (in Vietnamese). Báo Quảng Bình. November 16, 2020. Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- ↑ Valente, Catherine (November 15, 2020). "Task force to streamline typhoon recovery ordered". The Manila Times. Retrieved November 15, 2020.

- ↑ "PAGASA says Ulysses dumped less rain than Ondoy amid comparisons after heavy floods". ABS-CBN News. November 13, 2020. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ↑ "Duterte places entire Luzon under state of calamity". GMA News Online. November 17, 2020. Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- 1 2 "Robredo backs probe into oversights that may have led to Cagayan Valley floods". Philstar.com. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ↑ "Tuguegarao mayor apologizes for birthday trip during Typhoon Ulysses". Rappler. November 16, 2020. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ↑ "Tuguegarao mayor hit for bday AWOL". The Manila Times. November 16, 2020. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ↑ Madarang, Catalina Ricci S. (November 13, 2020). "'Project NOAH' and 'National Calamity Fund' create online buzz as Duterte bats for climate justice". Interaksyon. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- 1 2 "Roque denies information gap in Cagayan floods, but vows to 'do better' in disaster response". cnn. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ↑ "As Filipino resilience gets exploited, netizens slam gov't disaster response". Rappler. November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ↑ Salaverria, Leila B. (November 14, 2020). "Roque plea to netizens: Stop asking 'Nasaan ang Pangulo?'". INQUIRER.net. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ↑ Mendez, Christina. "Palace tells critics to dump #NasaanAngPangulo". Philstar.com. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ↑ "Criticism of Duterte during Ulysses 'kalokohan ng oposisyon' – Roque". Rappler. November 13, 2020. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ↑ "PRRD defends LGUs on 'Ulysses' response". Philippine Canadian Inquirer. November 15, 2020. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ↑ "Duterte sex jokes were meant to 'lighten the mood' — Palace". Philstar.com. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ↑ News, Jamaine Punzalan, ABS-CBN (November 16, 2020). "Duterte wants to 'lighten mood' with womanizing jokes in typhoon briefing: spokesman". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Sexist jokes are Duterte's way of coping with disasters – Roque". Rappler. November 16, 2020. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ↑ "Kids tell Leni of slippers on the roof, losing modules to Ulysses' floods". GMA News Online. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ↑ "DepEd to replace damaged learning modules due to typhoons". Rappler. November 16, 2020. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ↑ "In the aftermath of Typhoon Ulysses, Ateneo suspends classes, La Salle eases academic workload for one week". GMA News Online. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ↑ Ramos, Christia Marie (November 15, 2020). "Some universities suspend classes for at least 1 week after Ulysses". INQUIRER.net. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ↑ "Marikina suspends classes in all levels for a month". Rappler. November 16, 2020. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ↑ "PAGASA to retire "Ulysses" from its list of tropical cyclone names". Manila Bulletin. November 13, 2020. Retrieved November 13, 2020.

- ↑ Hallare, Katrina (January 27, 2021). "Pagasa 'retires' names given to previous devastating typhoons". Inquirer. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- ↑ Dost_pagasa (January 27, 2021). "Four tropical cyclone names from the 2020 list are now decommissioned: Ambo, Quinta, Rolly, and Ulysses. They will be replaced by Aghon, Querubin, Romina, and Upang, respectively, in the 2024 list". Retrieved January 27, 2021 – via Facebook.

- ↑ "53rd Session of TC - Working Doc Page". typhooncommittee.org. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ↑ http://typhooncommittee.org/54th/docs/item%2014/14.1%20Replacement%20of%20Typhoon%20Names.pdf

- ↑ "Tropical Cyclone Naming". public.wmo.int. May 30, 2016. Archived from the original on December 4, 2023. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

External links

- 25W.VAMCO from the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory

.jpg.webp)