| United States Army Special Operations Command (Airborne) | |

|---|---|

Distinctive unit insignia of USASOC Headquarters[1] | |

| Founded | 1 December 1989[2] |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Special warfare operations |

| Role | Organize, train, educate, man, equip, fund, administer, mobilize, deploy and sustain U.S. Army special operations forces to successfully conduct worldwide special warfare operations. |

| Size | 33,805 personnel authorized:[3]

|

| Part of | |

| Headquarters | Fort Liberty, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Motto(s) | "Sine Pari" (Without Equal) |

| Color of Beret | Tan Maroon Rifle green |

| Engagements | Invasion of Panama Persian Gulf War Unified Task Force Operation Gothic Serpent |

| Website | Official Website |

| Commanders | |

| Current commander | LTG Jonathan P. Braga |

| Notable commanders | LTG Francis M. Beaudette LTG Kenneth E. Tovo[2] Robert W. Wagner Edward M. Reeder Jr. John F. Mulholland Jr. Charles T. Cleveland |

| Insignia | |

| Combat service identification badge (metallic version of USASOC"s shoulder sleeve insignia) |  |

| Beret flash of the command |  |

The United States Army Special Operations Command (Airborne) (USASOC (/ˈjuːsəˌsɒk/ YOO-sə-sok[5])) is the command charged with overseeing the various special operations forces of the United States Army. Headquartered at Fort Liberty, North Carolina, it is the largest component of the United States Special Operations Command. It is an Army Service Component Command. Its mission is to organize, train, educate, man, equip, fund, administer, mobilize, deploy and sustain Army special operations forces to successfully conduct worldwide special operations.

Subordinate units

1st Special Forces Command (Airborne)

The ![]() 1st Special Forces Command (Airborne) is a division-level special operation forces command within the US Army Special Operations Command.[6] The command was established on 30 September 2014, grouping together the Army special forces, psychological operations, civil affairs, and other support troops into a single organization operating out of its new headquarters building at Fort Liberty, NC.

1st Special Forces Command (Airborne) is a division-level special operation forces command within the US Army Special Operations Command.[6] The command was established on 30 September 2014, grouping together the Army special forces, psychological operations, civil affairs, and other support troops into a single organization operating out of its new headquarters building at Fort Liberty, NC.

Special Forces Groups

Established in 1952, the Special Forces Groups, also known as the Green Berets, was established as a special operations force of the United States Army designed to deploy and execute nine doctrinal missions: unconventional warfare, foreign internal defense, direct action, counter-insurgency, special reconnaissance, counter-terrorism, information operations, counterproliferation of weapon of mass destruction, and security force assistance.[7] These missions make special forces unique in the U.S. military because they are employed throughout the three stages of the operational continuum: peacetime, conflict, and war.[8] Often SF units are required to perform additional, or collateral, activities outside their primary missions. These collateral activities are coalition warfare/support, combat search and rescue, security assistance, peacekeeping, humanitarian assistance, humanitarian de-mining, and counter-drug operations.[8] Their unconventional warfare capabilities provide a viable military option for a variety of operational taskings that are inappropriate or infeasible for conventional forces, making it the U.S. military's premier unconventional warfare force.[8]

Today, there are seven special forces groups, each one is primarily responsible for operations within a specific area of responsibility:

1st Special Forces Group (Airborne), (USINDOPACOM)

1st Special Forces Group (Airborne), (USINDOPACOM) 3rd Special Forces Group (Airborne), (AFRICOM)

3rd Special Forces Group (Airborne), (AFRICOM) 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne), (CENTCOM)

5th Special Forces Group (Airborne), (CENTCOM) 7th Special Forces Group (Airborne), (USSOUTHCOM)

7th Special Forces Group (Airborne), (USSOUTHCOM) 10th Special Forces Group (Airborne), (EUCOM)

10th Special Forces Group (Airborne), (EUCOM) 19th Special Forces Group (Airborne) (ARNG), (USINDOPACOM) and (CENTCOM)

19th Special Forces Group (Airborne) (ARNG), (USINDOPACOM) and (CENTCOM) 20th Special Forces Group (Airborne) (ARNG), (USSOUTHCOM)

20th Special Forces Group (Airborne) (ARNG), (USSOUTHCOM)

Psychological Operations Groups

The mission of the 4th Psychological Operations Group (Airborne) and 8th Psychological Operations Group (Airborne), a.k.a. PSYOP units, are to provide fully capable strategic influence forces to Combatant Commanders, U.S. Ambassadors, and other agencies to synchronize plans and execute inform and influence activities across the range of military operations via geographically focused PSYOP battalions.[9][10]

![]() 4th PSYOP Group (A) consists of five battalions:

4th PSYOP Group (A) consists of five battalions:

- 1st PSYOP Battalion (USSOUTHCOM)

5th PSYOP Battalion (USINDOPACOM)

5th PSYOP Battalion (USINDOPACOM)- 6th PSYOP Battalion (USEUCOM)

7th PSYOP Battalion (USAFRICOM)

7th PSYOP Battalion (USAFRICOM) 8th PSYOP Battalion (USCENTCOM)

8th PSYOP Battalion (USCENTCOM)

![]() The 8th PSYOP Group (A) consists of two battalions:

The 8th PSYOP Group (A) consists of two battalions:

3rd PSYOP Battalion (Dissemination)

3rd PSYOP Battalion (Dissemination)- 9th PSYOP Battalion (Tactical).

Psychological operations are a part of the broad range of U.S. political, military, economic and ideological activities used by the U.S. government to secure national objectives. Used during peacetime, contingencies, and declared war, these activities are not forms of force but are force multipliers that use nonviolent means in often violent environments. Persuading rather than compelling physically, they rely on logic, fear, desire, or other mental factors to promote specific emotions, attitudes or behaviors.[9]

The ultimate objective of U.S. PSYOP is to convince enemy, neutral, and friendly nations and forces to take action favorable to the United States and its allies. The ranks of the PSYOP include regional experts and linguists who understand political, cultural, ethnic, and religious subtleties and use persuasion to influence perceptions and encourage desired behavior. With functional experts in all aspects of tactical communications, PSYOP offers joint force commanders unmatched abilities to influence target audiences as well as strategic influence capabilities to U.S. diplomacy.[9]

In addition to supporting commanders, PSYOP units provide interagency strategic influence capabilities to other U.S. government agencies. In operations ranging from humanitarian assistance to drug interdiction, PSYOP enhances the impact of those agencies' actions. Their activities can be used to spread information about ongoing programs and to gain support from the local populace.[9]

95th Civil Affairs Brigade (Special Operations) (Airborne)

The ![]() 95th Civil Affairs Brigade (Special Operations) (Airborne) enables military commanders and U.S. Ambassadors to improve relationships with various stakeholders in a local area to meet the objectives of the U.S. government. 95th Civil Affairs Brigade (Airborne) teams work with U.S. Department of State country teams, government and nongovernmental organizations at all levels and with local populations in peaceful, contingency and hostile environments. 95th Civil Affairs Brigade (Airborne) units can rapidly deploy to remote areas with small villages and larger population centers around the world.[11]

95th Civil Affairs Brigade (Special Operations) (Airborne) enables military commanders and U.S. Ambassadors to improve relationships with various stakeholders in a local area to meet the objectives of the U.S. government. 95th Civil Affairs Brigade (Airborne) teams work with U.S. Department of State country teams, government and nongovernmental organizations at all levels and with local populations in peaceful, contingency and hostile environments. 95th Civil Affairs Brigade (Airborne) units can rapidly deploy to remote areas with small villages and larger population centers around the world.[11]

They help host nations assess the needs of an area, bring together local and non-local resources to ensure long-term stability, and ultimately degrade and defeat violent extremist organizations and their ideologies. They may be involved in disaster prevention, management, and recovery, and with human and civil infrastructure assistance programs.[11]

The 95th Civil Affairs Brigade (Airborne) conducts its mission via five geographically focused operational battalions:

91st Civil Affairs Battalion (USAFRICOM)

91st Civil Affairs Battalion (USAFRICOM) 92nd Civil Affairs Battalion (EUCOM)

92nd Civil Affairs Battalion (EUCOM) 96th Civil Affairs Battalion (USCENTCOM)

96th Civil Affairs Battalion (USCENTCOM) 97th Civil Affairs Battalion (USINDOPACOM)

97th Civil Affairs Battalion (USINDOPACOM) 98th Civil Affairs Battalion (USSOUTHCOM)

98th Civil Affairs Battalion (USSOUTHCOM)

The soldiers in these units are adept at working in foreign environments and conversing in one of about 20 foreign languages with local stakeholders. Brigade teams may work for months or years in remote areas of a host nation. Their low profile and command structure allow them to solidify key relationships and processes, to address root causes of instability that adversely affect the strategic interests of the United States.[11]

528th Sustainment Brigade (Special Operations) (Airborne)

The ![]() 528th Sustainment Brigade (SO) (A) is responsible for providing logistical, medical, signal, and intelligence support for Army special operations forces worldwide in support of contingency missions and war fighting commanders.[12] Headquartered at Fort Liberty, North Carolina, the 528th Sustainment Brigade (SO) (A) sets the operational level logistics conditions to enable Army Special Operation Forces (ARSOF) using multiple Support Operations teams and three battalions.[12][13][14][15]

528th Sustainment Brigade (SO) (A) is responsible for providing logistical, medical, signal, and intelligence support for Army special operations forces worldwide in support of contingency missions and war fighting commanders.[12] Headquartered at Fort Liberty, North Carolina, the 528th Sustainment Brigade (SO) (A) sets the operational level logistics conditions to enable Army Special Operation Forces (ARSOF) using multiple Support Operations teams and three battalions.[12][13][14][15]

The Support Operations teams embed each regional theaters' staff to support planning and coordination with theater Army, U.S. Special Operations Command and U.S. Army Special Operations Command to ensure support during operations and training. Support Operations consists of four detachments: current operations, which manages five geographically aligned ARSOF Liaison Elements (ALEs), a future operations detachment, a commodity managers detachment, and an ARSOF support operations element.[13][16]

The ![]() 528th Support Battalion provides rapidly deployable combat service support and health service support to ARSOF and consists of a headquarters company with an organic rigger detachment, a special operations medical detachment with four Austere Resuscitative Surgical Teams (ARSTs),[17][18] the

528th Support Battalion provides rapidly deployable combat service support and health service support to ARSOF and consists of a headquarters company with an organic rigger detachment, a special operations medical detachment with four Austere Resuscitative Surgical Teams (ARSTs),[17][18] the ![]() 197th Special Troops Support Company from the Texas Army National Guard, and 1/528th Forward Support Company from the West Virginia Army National Guard.[13][19]

197th Special Troops Support Company from the Texas Army National Guard, and 1/528th Forward Support Company from the West Virginia Army National Guard.[13][19]

The ![]() 112th Special Operations Signal Battalion specializes in communication, employing innovative telecommunications technologies to provide Special Operations Joint Task Force (SOJTF) commanders with secure and nonsecure voice, data and video services. The 112th's signals expertise allows ARSOF to "shoot, move and communicate" on a continuous basis. Soldiers assigned to 112th are taught to operate and maintain a vast array of unique equipment not normally used by their conventional counterparts. To meet the needs of ARSOF, the 112th deploys communications packages that are rapidly deployable on a moment's notice. Soldiers assigned to 112th are airborne qualified.[12]

112th Special Operations Signal Battalion specializes in communication, employing innovative telecommunications technologies to provide Special Operations Joint Task Force (SOJTF) commanders with secure and nonsecure voice, data and video services. The 112th's signals expertise allows ARSOF to "shoot, move and communicate" on a continuous basis. Soldiers assigned to 112th are taught to operate and maintain a vast array of unique equipment not normally used by their conventional counterparts. To meet the needs of ARSOF, the 112th deploys communications packages that are rapidly deployable on a moment's notice. Soldiers assigned to 112th are airborne qualified.[12]

The ![]() 389th Military Intelligence Battalion was established in March 2015 and conducts command and control of multi-disciplined intelligence operations in support of the 1st Special Forces Command (A) G2, component subordinate units, and mission partners via three companies: a headquarters company; an Analytical Support Company with a cytological support element and five geographically aligned regional support teams; a Mission Support Company with a Processing, Exploitation, and Dissemination (PED) detachment, a HUMINT and GEOINT detachment, and conducts the Special Warfare SIGINT Course; and an additional PED detachment at Fort Eisenhower. On order, it deploys and conducts intelligence operations as part of a Special Operations Joint Task Force (SOJTF).[15][20]

389th Military Intelligence Battalion was established in March 2015 and conducts command and control of multi-disciplined intelligence operations in support of the 1st Special Forces Command (A) G2, component subordinate units, and mission partners via three companies: a headquarters company; an Analytical Support Company with a cytological support element and five geographically aligned regional support teams; a Mission Support Company with a Processing, Exploitation, and Dissemination (PED) detachment, a HUMINT and GEOINT detachment, and conducts the Special Warfare SIGINT Course; and an additional PED detachment at Fort Eisenhower. On order, it deploys and conducts intelligence operations as part of a Special Operations Joint Task Force (SOJTF).[15][20]

U.S. Army Special Operations Aviation Command (Airborne)

The ![]() U.S. Army Special Operations Aviation Command (USASOAC), activated on 25 March 2011, organizes, mans, trains, resources and equips Army special operations aviation units to provide responsive, special operations aviation support to Special Operations Forces (SOF) and is the USASOC aviation staff proponent.[21] Today, USASOAC consists of five distinct units: the

U.S. Army Special Operations Aviation Command (USASOAC), activated on 25 March 2011, organizes, mans, trains, resources and equips Army special operations aviation units to provide responsive, special operations aviation support to Special Operations Forces (SOF) and is the USASOC aviation staff proponent.[21] Today, USASOAC consists of five distinct units: the ![]() 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (Airborne), the USASOC Flight Company (UFC), the Special Operations Training Battalion (SOATB), the Technology Applications Program Office (TAPO), and the Systems Integration Management Office (SIMO).

160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (Airborne), the USASOC Flight Company (UFC), the Special Operations Training Battalion (SOATB), the Technology Applications Program Office (TAPO), and the Systems Integration Management Office (SIMO).

The 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (Airborne), newly subordinate to ARSOAC,[22] provides aviation support to special operations forces. Known as "Night Stalkers," these soldiers are recognized for their proficiency in nighttime operations striking undetected during the hours of darkness and are recognized as the pioneers of the US Army's nighttime flying techniques. Today, Night Stalkers continue developing and employing new technology and tactics, techniques and procedures for the battlefield. They employ highly modified heavy assault versions of the MH-47 Chinook, medium assault and attack versions of the MH-60 Black Hawk, light assault and attack versions of the MH-6 Little Bird helicopters,[23] and MQ-1C Gray Eagles via four battalions, two Extended-Range Multi-Purpose (ERMP) companies, a headquarters company, and a training company. The ![]() 1st Battalion,

1st Battalion, ![]() 2nd Battalion, the regiment, and its ERMP companies are stationed at Fort Campbell,

2nd Battalion, the regiment, and its ERMP companies are stationed at Fort Campbell, ![]() 3rd Battalion is at Hunter Army Airfield, and

3rd Battalion is at Hunter Army Airfield, and ![]() 4th Battalion is at Joint Base Lewis–McChord.[24]

4th Battalion is at Joint Base Lewis–McChord.[24]

75th Ranger Regiment

The ![]() 75th Ranger Regiment, also known as the Rangers, is an airborne light-infantry special operations unit. The regiment is headquartered at Fort Moore, Georgia and is composed of a regimental airborne special troops battalion, a regimental airborne military intelligence battalion, and three airborne light-infantry battalions. The

75th Ranger Regiment, also known as the Rangers, is an airborne light-infantry special operations unit. The regiment is headquartered at Fort Moore, Georgia and is composed of a regimental airborne special troops battalion, a regimental airborne military intelligence battalion, and three airborne light-infantry battalions. The ![]() 1st Ranger Battalion is stationed at Hunter Army Airfield,

1st Ranger Battalion is stationed at Hunter Army Airfield, ![]() 2nd Ranger Battalion at Joint Base Lewis–McChord, and

2nd Ranger Battalion at Joint Base Lewis–McChord, and ![]() 3rd Ranger Battalion is at Fort Moore (formerly Fort Benning) along with the special troops battalion, the military intelligence battalion, and regimental headquarters.

3rd Ranger Battalion is at Fort Moore (formerly Fort Benning) along with the special troops battalion, the military intelligence battalion, and regimental headquarters.

Within the US special operations community, the 75th Ranger Regiment is unique with its ability to attack heavily defended targets of interest. The regiment specializes in air assault, direct action raids, seizure of key terrain (such as airfields), destroying strategic facilities, and capturing or killing high-profile individuals. Each battalion of the regiment can deploy anywhere in the world within 18 hours' notice. Rangers can conduct squad through regimental-size operations using a variety of insertion techniques including airborne, air assault, and ground infiltration. The regiment is an all-volunteer force with an intensive screening and selection process followed by combat-focused training. Rangers are resourced to maintain exceptional proficiency, experience and readiness.[25]

U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School

The ![]() U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School (SWCS) at Fort Liberty, North Carolina, is one of the Army's premier education institutions, managing and resourcing professional growth for soldiers in the Army's three distinct special-operations branches: Special Forces, Civil Affairs and Psychological Operations. The soldiers educated through SWCS programs are using cultural expertise and unconventional techniques to serve their country in far-flung areas across the globe. More than anything, these soldiers bring integrity, adaptability and regional expertise to their assignments.[26]

U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School (SWCS) at Fort Liberty, North Carolina, is one of the Army's premier education institutions, managing and resourcing professional growth for soldiers in the Army's three distinct special-operations branches: Special Forces, Civil Affairs and Psychological Operations. The soldiers educated through SWCS programs are using cultural expertise and unconventional techniques to serve their country in far-flung areas across the globe. More than anything, these soldiers bring integrity, adaptability and regional expertise to their assignments.[26]

On any given day, approximately 3,100 students are enrolled in SWCS training programs. Courses range from entry-level training to advanced warfighter skills for seasoned officers and NCOs. The ![]() 1st Special Warfare Training Group (Airborne) qualifies soldiers to enter the special operations community. The

1st Special Warfare Training Group (Airborne) qualifies soldiers to enter the special operations community. The ![]() 2nd Special Warfare Training Group (Airborne) focuses on teaches special operators advanced tactical skills as they progress through their careers. The Joint Special Operations Medical Training Center, operating under the auspices of the

2nd Special Warfare Training Group (Airborne) focuses on teaches special operators advanced tactical skills as they progress through their careers. The Joint Special Operations Medical Training Center, operating under the auspices of the ![]() Special Warfare Medical Group, is the central training facility for the Department of Defense special operations combat medics. Furthermore, SWCS leads efforts to professionalize the Army's entire special operations force through the

Special Warfare Medical Group, is the central training facility for the Department of Defense special operations combat medics. Furthermore, SWCS leads efforts to professionalize the Army's entire special operations force through the ![]() Special Forces Warrant Officer Institute and the

Special Forces Warrant Officer Institute and the ![]() David K. Thuma Noncommissioned Officer Academy. While most courses are conducted at Fort Liberty, SWCS enhances its training by maintaining facilities and relationships with outside institutions across the country.[26]

David K. Thuma Noncommissioned Officer Academy. While most courses are conducted at Fort Liberty, SWCS enhances its training by maintaining facilities and relationships with outside institutions across the country.[26]

1st Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta

The 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta (1st SFOD-D), commonly referred to as Delta Force, Combat Applications Group (CAG), "The Unit", Army Compartmented Element, or within the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) as Task Force Green,[27] is an elite special mission unit of the United States Army, under the organization of USASOC, but controlled by JSOC. It is used for hostage rescue and counterterrorism, as well as direct action and reconnaissance against high-value targets. 1st SFOD-D and its U.S. Navy and U.S. Air Force counterparts, DEVGRU, "SEAL Team 6", and the 24th Special Tactics Squadron, perform the most highly complex and dangerous missions in the U.S. military. These units are also often referred to as "Tier One" and "special mission units" by the U.S. government.

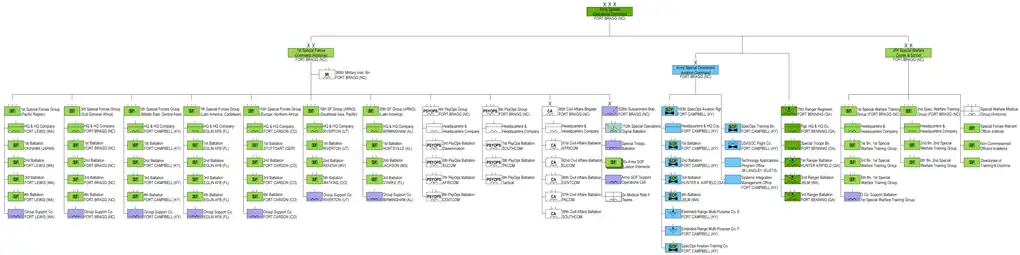

Order of Battle

List of commanding generals

| No. | Commanding General | Term | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Portrait | Name | Took office | Left office | Term Length | |

| 1 | Lieutenant General Gary E. Luck (born 1937) | 1 December 1989 | June 1990 | ~182 days | |

| 2 | Lieutenant General Michael F. Spigelmire (born 1938) | June 1990 | August 1991 | ~1 year, 61 days | |

| 3 | Lieutenant General Wayne A. Downing (1940–2007) | August 1991 | May 1993 | ~1 year, 273 days | |

| 4 | Lieutenant General James T. Scott (born 1942) | May 1993 | October 1996 | ~3 years, 153 days | |

| 5 | Lieutenant General Peter Schoomaker[29] (born 1946) | October 1996 | October 1997 | ~1 year, 0 days | |

| 6 | Lieutenant General William P. Tangney | October 1997 | 11 October 2000 | ~3 years, 10 days | |

| 7 | Lieutenant General Bryan D. Brown (born 1948) | 11 October 2000 | 29 August 2002 | 1 year, 322 days | |

| 8 | Lieutenant General Philip R. Kensinger Jr. | 29 August 2002 | 8 December 2005 | 3 years, 101 days | |

| 9 | Lieutenant General Robert W. Wagner | 8 December 2005 | 7 November 2008 | 2 years, 335 days | |

| 10 | Lieutenant General John F. Mulholland Jr.[31] (born 1955) | 7 November 2008 | 24 July 2012 | 3 years, 260 days | |

| 11 | Lieutenant General Charles T. Cleveland (born 1956) | 24 July 2012 | 1 July 2015 | 2 years, 342 days | |

| 12 | Lieutenant General Kenneth E. Tovo (born 1961) | 1 July 2015 | 8 June 2018 | 2 years, 342 days | |

| 13 | Lieutenant General Francis M. Beaudette | 8 June 2018 | 13 August 2021 | 3 years, 66 days | |

| 14 | Lieutenant General Jonathan P. Braga (born 1969) | 13 August 2021 | Incumbent | 2 years, 147 days | |

References

- ↑ U.S. Army Special Operations Command, Distinctive Unit Insignia, United States Army Institute of Heraldry, last accessed 12 February 2017

- 1 2 SOCOM Fact Book 2014 (PDF). SOCOM Public Affairs. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 December 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ↑ http://www.gao.gov/assets/680/671462.pdf

- ↑ Shoulder Sleeve Insignia: U.S. ARMY SPECIAL OPERATIONS COMMAND, U.S. Army Institute of Heraldry, dated 1 December 1989, last accessed 30 December 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ "Chaplain Forte". Facebook. 9 April 2020. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ↑ Trevithick, Joseph (26 November 2014). "The U.S. Army Has Quietly Created a New Commando Division". Medium.com. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ↑ Army Special Operations Forces Fact Book 2018 Archived 19 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine, USASOC official website, dated 2018, last accessed 28 July 2019

- 1 2 3 U.S. Army Special Forces Command. Archived from the original on 20 December 2010. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "MISOC Units Re-designate as PSYOP – ShadowSpear Special Operations". Shadowspear.com. 13 December 2015. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ↑ The Army's psychological operations community is getting its name back, Army Times, by Meghann Myers, dated 6 November 2017, last accessed 4 March 2018

- 1 2 3 95th Civil Affairs Brigade. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- 1 2 3 528th Sustainment Brigade. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- 1 2 3 528th Sustainment Brigade, Special Operations (Airborne), soc.mil, last accessed 13 December 2020

- ↑ 528th Special Operations Sustainment Brigade Organizational Chart 2020, 528th Sustainment Brigade History Handbook Published by the U.S. Army Special Operations Command History Office Fort Bragg, North Carolina 2020, by Chris Howard ARSOF Support Historian, dated 5 December 2020, last accessed 12 December 2020

- 1 2 FROM LEYTE TO THE LEVANT, A Brief History of the 389th Military Intelligence Battalion (Airborne), Office of the Command Historian (USASOC), by Christopher E. Howard, dated 2019, last accessed 27 November 2020

- ↑ 528th Special Operations Sustainment Brigade Support Operations Organizational Chart 2020, 528th Sustainment Brigade History Handbook Published by the U.S. Army Special Operations Command History Office Fort Bragg, North Carolina 2020, by Chris Howard ARSOF Support Historian, dated 5 December 2020, last accessed 12 December 2020

- ↑ The Special Operations Resuscitation Team: Robust Role II Medical Support for Today’s SOF Environment; Journal of Special Operations Medicine Volume 9, Edition 1, Winter 09; by Jamie Riesberg, MD; last accessed 13 December 2020

- ↑ The Special Operations Resuscitation Team: Robust Role II Medical Support for Today’s SOF Environment, Journal of Special Operations Medicine, Volume 9 / Edition 1 / Winter 2009, by Jamie Riesberg (MD), last accessed 22 October 2016

- ↑ 528th Sustainment Brigade Special Troops Battalion Organizational Chart 2020, 528th Sustainment Brigade History Handbook Published by the U.S. Army Special Operations Command History Office Fort Bragg, North Carolina 2020, by Chris Howard ARSOF Support Historian, dated 5 December 2020, last accessed 12 December 2020

- ↑ 528th Sustainment Brigade - 389th MI Battalion Organizational Chart 2020, 528th Sustainment Brigade History Handbook Published by the U.S. Army Special Operations Command History Office Fort Bragg, North Carolina 2020, by Chris Howard ARSOF Support Historian, dated 5 December 2020, last accessed 12 December 2020

- ↑ Archived 14 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Night Stalkers mark new lineage with donning of USASOAC patch | Article | The United States Army". Army.mil. 3 October 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ↑ 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (Airborne), soc.mil, last accessed 9 October 2016

- ↑ Army's Elite Night Stalkers Quietly Stood Up A New Unit Ahead Of Getting New Drones, thedrive.com, By Joseph Trevithick, dated 8 February 2019, last accessed 12 February 2019

- ↑ 75th Ranger Regiment, The Army's Premier Raid Force, United States Army Special Operations Command Homepage, last accessed 20 May 2017

- 1 2 About SWCS. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ↑ Naylor, Sean. "Chapter 4". Relentless Strike.

- "Peter Jan Schoomaker". History.army.mil. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ↑ "Peter Jan Schoomaker". History.army.mil. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- "Outgoing USASOC commander sees growing demand for special operations". Archived from the original on 29 June 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ↑ "Outgoing USASOC commander sees growing demand for special operations". Archived from the original on 29 June 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

External links

- U.S. Army Special Operations Command Archived 13 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine—official site

- U.S. Army Special Operations Command News

.jpg.webp)