_-_NH_2063_-_cropped.jpg.webp) SMS Frankfurt as a target ship | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Frankfurt |

| Namesake | Frankfurt |

| Builder | Kaiserliche Werft, Kiel |

| Laid down | 1913 |

| Launched | 20 March 1915 |

| Commissioned | 20 August 1915 |

| Fate | Ceded to the United States after World War I |

| Name | USS Frankfurt |

| Acquired | 11 March 1920 |

| Commissioned | 4 June 1920 |

| Fate | Sunk as a target, 18 July 1921 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Wiesbaden-class light cruiser |

| Displacement |

|

| Length | 145.3 m (477 ft) |

| Beam | 13.9 m (46 ft) |

| Draft | 5.76 m (18.9 ft) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h) |

| Range | 4,800 nmi (8,900 km; 5,500 mi) at 12 kn (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Crew |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

SMS Frankfurt was a light cruiser of the Wiesbaden class built by the German Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial Navy). She had one sister ship, SMS Wiesbaden; the ships were very similar to the previous Karlsruhe-class cruisers. The ship was laid down in 1913, launched in March 1915, and completed by August 1915. Armed with eight 15 cm SK L/45 guns, Frankfurt had a top speed of 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph) and displaced 6,601 t (6,497 long tons; 7,276 short tons) at full load.

Frankfurt saw extensive action with the High Seas Fleet during World War I. She served primarily in the North Sea, and participated in the Bombardment of Yarmouth and Lowestoft and the battles of Jutland and Second Heligoland. At Jutland, she was lightly damaged by a British cruiser and her crew suffered minor casualties. At the end of the war, she was interned with the bulk of the German fleet in Scapa Flow. When the fleet was scuttled in June 1919, Frankfurt was one of the few ships that were not successfully sunk. She was ceded to the US Navy as a war prize and ultimately expended as a bomb target in tests conducted by the US Navy and Army Air Force in July 1921.

Design

Frankfurt was 145.3 meters (477 ft) long overall and had a beam of 13.9 m (46 ft) and a draft of 5.76 m (18.9 ft) forward. She displaced 6,601 t (6,497 long tons; 7,276 short tons) at full load. Her propulsion system consisted of two sets of Marine steam turbines driving two 3.5-meter (11 ft) screw propellers. They were designed to give 31,000 shaft horsepower (23,000 kW). These were powered by ten coal-fired Marine-type water-tube boilers and two oil-fired double-ended boilers. These gave the ship a top speed of 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph). Frankfurt carried 1,280 t (1,260 long tons) of coal, and an additional 470 t (460 long tons) of oil that gave her a range of 4,800 nautical miles (8,900 km; 5,500 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph). Frankfurt had a crew of 17 officers and 457 enlisted men.[1]

The ship was armed with a main battery of eight 15 cm (5.9 in) SK L/45 guns in single pedestal mounts. Two were placed side by side forward on the forecastle, four were located amidships, two on either side, and two were placed in a superfiring pair aft. The guns could engage targets out to 17,600 m (57,700 ft). They were supplied with 1,024 rounds of ammunition, for 128 shells per gun. The ship's antiaircraft armament initially consisted of four 5.2 cm (2 in) L/55 guns, though these were replaced with a pair of 8.8 cm (3.5 in) SK L/45 anti-aircraft guns. She was also equipped with four 50 cm (19.7 in) torpedo tubes with eight torpedoes. Two were submerged in the hull on the broadside and two were mounted on the deck amidships. She could also carry 120 mines. The ship was protected by a waterline armored belt that was 60 mm (2.4 in) thick amidships. The conning tower had 100 mm (3.9 in) thick sides, and the deck was covered with up to 60 mm thick armor plate.[2]

Service history

Frankfurt was ordered under the contract name "Ersatz Hela" and was laid down at the Kaiserliche Werft shipyard in Kiel in 1913 and launched on 20 March 1915, after which fitting-out work commenced. She was commissioned into the High Seas Fleet on 20 August 1915,[2] after being rushed through sea trials.[3] The first operation in which Frankfurt saw action was the Bombardment of Yarmouth and Lowestoft on 24 April 1916. Frankfurt was assigned to the reconnaissance screen for the battlecruisers of I Scouting Group, temporarily under the command of Konteradmiral Friedrich Boedicker's. During the raid, Frankfurt attacked and sank a British armed patrol boat off the English coast.[4] Due to reports of British submarines and torpedo attacks, Boedicker broke off the chase, and turned back east towards the High Seas Fleet. At this point, the German fleet commander, Vice Admiral Reinhard Scheer, who had been warned of the Grand Fleet's sortie from Scapa Flow, turned back towards Germany.[5]

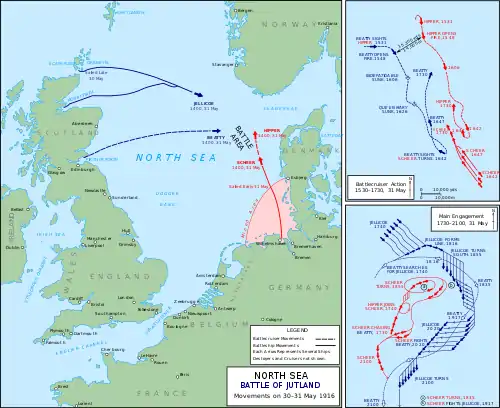

Battle of Jutland

At the Battle of Jutland on 31 May – 1 June 1916, Frankfurt served as Boedicker's flagship, the commander of II Scouting Group. II Scouting Group was again screening for the I Scouting Group battlecruisers, again commanded by Vizeadmiral Franz von Hipper. Frankfurt was engaged in the first action of the battle, when the cruiser screens of the German and British battlecruiser squadrons encountered each other. Frankfurt, Pillau, and Elbing briefly fired on the British light cruisers at 16:17 until the British ships turned away. Half an hour later, the fast battleships of the 5th Battle Squadron had reached the scene and opened fire on Frankfurt and the other German cruisers, though the ships quickly fled under a smokescreen and were not hit.[6]

Shortly before 18:00, the British destroyers Onslow and Moresby attempted to attack the German battlecruisers. Heavy fire from Frankfurt and Pillau forced the British ships to break off the attack.[7] At around 18:30, Frankfurt and the rest of II Scouting Group encountered the cruiser HMS Chester; they opened fire and scored several hits on the ship. Rear Admiral Horace Hood's three battlecruisers intervened, however, and scored a hit on Wiesbaden that disabled the ship.[8] About an hour later, Canterbury scored four hits on Frankfurt in quick succession: two 6-inch (150 mm) hits in the area of Frankfurt's mainmast and a pair of 4-inch (100 mm) hits. One of the 4-inch shells hit forward, well above the waterline, and the second exploded in the water near the stern and damaged both screws.[9]

Frankfurt and Pillau spotted the cruiser Castor and several destroyers shortly before 23:00. They each fired a torpedo at the British cruiser before turning back toward the German line without using their searchlights or guns to avoid drawing the British toward the German battleships. Almost two hours later, Frankfurt encountered a pair of British destroyers and fired on them briefly until they retreated at full speed.[10] By 04:00 on 1 June, the German fleet had evaded the British fleet and reached Horns Reef.[11] Frankfurt had three men killed and eighteen wounded in the course of the engagement. She had fired 379 rounds of 15 cm ammunition and a pair of 8.8 cm shells, and launched a single torpedo.[12]

Subsequent operations

The ship participated in Operation Albion in October 1917, an operation to eliminate the Russian naval forces that still held the Gulf of Riga. The ship was part of II Scouting Group, commanded by Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter.[13] The following month, Frankfurt and the rest of II Scouting Group were engaged during the Second Battle of Heligoland Bight. Along with three other cruisers from II Scouting Group, Königsberg escorted minesweepers clearing paths in minefields laid by the British. The dreadnought battleships Kaiser and Kaiserin stood by in distant support.[14] During the battle, Frankfurt fired torpedoes at the attacking British cruisers, but failed to score any hits.[15] The British broke off the attack when the German battleships arrived on the scene, after which the Germans also withdrew.[16]

At 19:08 on 21 October 1918,[17] Frankfurt accidentally rammed and sank the U-boat UB-89 in Kiel-Holtenau, killing seven of her crew. Twenty-seven survivors were pulled from the water.[18] UB-89 was raised by the salvage tug Cyclop on 30 October but with the war almost over, she was not repaired and did not see further service.[17][19]

In the final weeks of the war, Scheer and Hipper intended to inflict as much damage as possible on the British navy, in order to secure a better bargaining position for Germany, whatever the cost to the fleet. On the morning of 29 October 1918, the order was given to sail from Wilhelmshaven the following day. Starting on the night of 29 October, sailors on Thüringen and then on several other battleships mutinied. The unrest ultimately forced Hipper and Scheer to cancel the operation. Most of the High Seas Fleet's ships, including Frankfurt, were interned in the British naval base in Scapa Flow, under the command of Reuter.[20]

Fate

The fleet remained in captivity during the negotiations that ultimately produced the Versailles Treaty. Reuter believed that the British intended to seize the German ships on 21 June 1919, which was the deadline for Germany to have signed the peace treaty. Unaware that the deadline had been extended to the 23rd, Reuter ordered the ships to be sunk at the next opportunity. On the morning of 21 June, the British fleet left Scapa Flow to conduct training maneuvers, and at 11:20 Reuter transmitted the order to scuttle his ships.[21] British sailors boarded Frankfurt and beached her before she could sink.[22] She was raised the following month and thereafter transferred to the United States Navy as a war prize.[23]

She was formally taken over on 11 March 1920 in England and commissioned into the US Navy on 4 June.[24] As she had been damaged in the scuttling, she was taken under tow by the minesweepers Redwing, Rail, and Falcon and taken to Brest, France, where the ex-German battleship SMS Ostfriesland, which had also been ceded to the United States, took Frankfurt under tow. The three minesweepers then towed three ex-German torpedo boats in company with Ostfriesland and Frankfurt; the convoy then crossed the Atlantic to the New York Navy Yard. There, the ships were thoroughly inspected by naval engineers to determine the advantages and disadvantages of the German ships, with the goal of incorporating any lessons learned into future American designs. While there, she also had her watertight compartments completely sealed to improve her ability to remain afloat when damaged.[25][26]

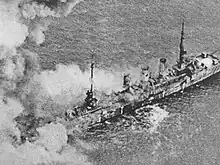

In July 1921, the Army Air Service and the US Navy conducted a series of bombing tests off Cape Henry, Virginia, led by General Billy Mitchell. The targets included demobilized American and former German warships, including the old battleship Iowa, Frankfurt, and Ostfriesland. Frankfurt was scheduled for tests conducted on 18 July.[26] The attacks started with small 250-pound (110 kg) and 300 lb (140 kg) bombs, which caused minor hull damage. The bombers then changed over to larger 550 lb (250 kg) and 600 lb (270 kg) bombs; Army Air Service Martin MB-2 bombers hit Frankfurt with several of the 600 lb bombs and sank the ship at 18:25.[23][27]

Ostfriesland, Frankfurt, and other captured German ships off the Virginia Capes, July 1921

Ostfriesland, Frankfurt, and other captured German ships off the Virginia Capes, July 1921 Aerial photo of Frankfurt moored during the test, with white targets painted on her deck

Aerial photo of Frankfurt moored during the test, with white targets painted on her deck.jpg.webp)

Frankfurt burning during bombing tests

Frankfurt burning during bombing tests Frankfurt sinks

Frankfurt sinks

Footnotes

- ↑ Gröner, p. 111.

- 1 2 Gröner, pp. 111–112.

- ↑ Campbell & Sieche, p. 162.

- ↑ Scheer, p. 128.

- ↑ Tarrant, p. 54.

- ↑ Tarrant, pp. 62, 75, 96.

- ↑ Campbell, p. 100.

- ↑ Tarrant, pp. 127–128.

- ↑ Campbell, pp. 149, 392.

- ↑ Campbell, pp. 279, 292.

- ↑ Tarrant, pp. 246–247.

- ↑ Campbell, pp. 341, 360, 401.

- ↑ Staff, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Woodward, p. 90.

- ↑ Scheer, p. 307.

- ↑ Halpern, p. 377.

- 1 2 Herzog, p. 95.

- ↑ Gray, p. 246.

- ↑ Willmott, p. 437.

- ↑ Tarrant, pp. 280–282.

- ↑ Herwig, p. 256.

- ↑ Woodward, p. 183.

- 1 2 Gröner, p. 112.

- ↑ "Frankfurt". Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ↑ Dodson, p. 145.

- ↑ Miller, p. 32.

References

- Campbell, John (1998). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-1-55821-759-1.

- Campbell, N. J. M. & Sieche, Erwin (1986). "Germany". In Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 134–189. ISBN 978-0-85177-245-5.

- Dodson, Aidan (2017). "After the Kaiser: The Imperial German Navy's Light Cruisers after 1918". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2017. London: Conway. pp. 140–159. ISBN 978-1-8448-6472-0.

- Gray, Edwyn (1996). Few Survived: A History of Submarine Disasters. Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-0-85052-499-4.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-352-7.

- Herwig, Holger (1980). "Luxury" Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Amherst: Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-286-9.

- Herzog, Bodo (1968). 60 Jahre deutsche Uboote 1906-1966. München: J.F. Lehmann. OCLC 5417475.

- Miller, Roger G. (2009). Billy Mitchell: Stormy Petrel of the Air. Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History. OCLC 56356772.

- Scheer, Reinhard (1920). Germany's High Seas Fleet in the World War. London: Cassell and Company. OCLC 52608141.

- Staff, Gary (2008). Battle for the Baltic Islands. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Maritime. ISBN 978-1-84415-787-7.

- Tarrant, V. E. (1995). Jutland: The German Perspective. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-304-35848-9.

- "The Naval Bombing Experiments Off the Virginia Capes – June and July 1921". Naval History & Heritage Command. 9 April 2015. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- Willmott, H. P. (2009). The Last Century of Sea Power (Volume 1, From Port Arthur to Chanak, 1894–1922). Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-35214-9.

- Woodward, David (1973). The Collapse of Power: Mutiny in the High Seas Fleet. London: Arthur Barker Ltd. ISBN 978-0-213-16431-7.

Further reading

- Dodson, Aidan; Cant, Serena (2020). Spoils of War: The Fate of Enemy Fleets after the Two World Wars. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5267-4198-1.

- Dodson, Aidan; Nottelmann, Dirk (2021). The Kaiser's Cruisers 1871–1918. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-68247-745-8.