Ulf Merbold | |

|---|---|

Official portrait for STS-42, 1991 | |

| Born | 20 June 1941 |

| Status | Retired |

| Occupation | Physicist |

| Space career | |

| ESA astronaut | |

Time in space | 49 days |

| Selection | 1978 ESA Group |

| Missions | STS-9, STS-42, Euromir 94 (Soyuz TM-20/TM-19) |

Mission insignia | |

Ulf Dietrich Merbold (German: [ʊlf ˈdiːtrɪç ˈmɛrbɔlt]; born 20 June 1941) is a German physicist and astronaut who flew to space three times, becoming the first West German citizen in space and the first non-American to fly on a NASA spacecraft. Merbold flew on two Space Shuttle missions and on a Russian mission to the space station Mir, spending a total of 49 days in space.

Merbold's father was imprisoned in NKVD special camp Nr. 2 by the Red Army in 1945 and died there in 1948, and Merbold was brought up in the town of Greiz in East Germany by his mother and grandparents. As he was not allowed to attend university in East Germany, he left for West Berlin in 1960, planning to study physics there. After the Berlin Wall was built in 1961, he moved to Stuttgart, West Germany. In 1968, he graduated from the University of Stuttgart with a diploma in physics, and in 1976 he gained a doctorate with a dissertation about the effect of radiation on iron. He then joined the staff at the Max Planck Institute for Metals Research.

In 1977, Merbold successfully applied to the European Space Agency (ESA) to become one of their first astronauts. He started astronaut training with NASA in 1978. In 1983, Merbold flew to space for the first time as a payload specialist or science astronaut on the first Spacelab mission, STS-9, aboard the Space Shuttle Columbia. He performed experiments in materials science and on the effects of microgravity on humans. In 1989, Merbold was selected as payload specialist for the International Microgravity Laboratory-1 (IML-1) Spacelab mission STS-42, which launched in January 1992 on the Space Shuttle Discovery. Again, he mainly performed experiments in life sciences and materials science in microgravity. After ESA decided to cooperate with Russia, Merbold was chosen as one of the astronauts for the joint ESA–Russian Euromir missions and received training at the Russian Yuri Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center. He flew to space for the third and last time in October 1994, spending a month working on experiments on the Mir space station.

Between his space flights, Merbold provided ground-based support for other ESA missions. For the German Spacelab mission Spacelab D-1, he served as backup astronaut and as crew interface coordinator. For the second German Spacelab mission D-2 in 1993, Merbold served as science coordinator. Merbold's responsibilities for ESA included work at the European Space Research and Technology Centre on the Columbus program and service as head of the German Aerospace Center's astronaut office. He continued working for ESA until his retirement in 2004.

Early life and education

Ulf Merbold was born in Greiz, in the Vogtland area of Thuringia, on 20 June 1941.[1][2] He was the only child of two teachers who lived in the school building of Wellsdorf, a small village.[3][4] During World War II, Ulf's father Herbert Merbold was a soldier who was imprisoned and then released from an American prisoner of war camp in 1945. Soon after, he was imprisoned by the Red Army in NKVD special camp Nr. 2, where he died on 23 February 1948.[3][5][6] Merbold's mother Hildegard was dismissed from her school by the Soviet zone authorities in 1945.[7][8][9] She and her son moved to a house in Kurtschau,[10] a suburb of Greiz, where Merbold grew up close to his maternal grandparents and his paternal grandfather.[9]

After graduating in 1960 from Theodor-Neubauer-Oberschule high school—now Ulf-Merbold-Gymnasium Greiz—in Greiz,[3] Merbold wanted to study physics at the University of Jena.[11][12] Because he had not joined the Free German Youth, the youth organization of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany, he was not allowed to study in East Germany so he decided to go to Berlin, and crossed into West Berlin by bicycle.[12][13] He obtained a West German high school diploma (Abitur) in 1961, as West German universities did not accept the East German one,[14] and intended to start studying in Berlin so he could occasionally see his mother.[11][15]

When the Berlin Wall was built on 13 August 1961, it became impossible for Ulf's mother to visit him.[16] Merbold then moved to Stuttgart, where he had an aunt,[11] and started studying physics at the University of Stuttgart, graduating with a Diplom in 1968.[1] He lived in a dormitory in a wing of Solitude Palace.[17] Thanks to an amnesty for people who had left East Germany, Merbold could again see his mother from late December 1964.[11] In 1976, Merbold obtained a doctorate in natural sciences, also from the University of Stuttgart,[1] with a dissertation titled Untersuchung der Strahlenschädigung von stickstoffdotierten Eisen nach Neutronenbestrahlung bei 140 Grad Celsius mit Hilfe von Restwiderstandsmessungen on the effects of neutron radiation on nitrogen-doped iron.[18] After completing his doctorate, Merbold became a staff member at the Max Planck Institute for Metals Research in Stuttgart, where he had held a scholarship from 1968.[8] At the institute, he worked on solid-state and low-temperature physics,[15] with a special focus on experiments regarding lattice defects in body-centered cubic (bcc) materials.[1]

Astronaut training

In 1973, NASA and the European Space Research Organisation, a precursor organization of the European Space Agency (ESA),[19] agreed to build a scientific laboratory that would be carried on the Space Shuttle, then under development.[20] The memorandum of understanding contained the suggestion the first flight of Spacelab should have a European crew member on board.[21] The West German contribution to Spacelab was 53.3% of the cost; 52.6% of the work contracts were carried out by West German companies, including the main contractor ERNO.[22]

In March 1977, ESA issued an Announcement of Opportunity for future astronauts, and several thousand people applied.[23] Fifty-three of these underwent an interview and assessment process that started in September 1977, and considered their skills in science and engineering as well as their physical health.[24] Four of the applicants were chosen as ESA astronauts; these were Merbold, Italian Franco Malerba, Swiss Claude Nicollier and Dutch Wubbo Ockels.[23] The French candidate Jean-Loup Chrétien was not selected, angering the President of France. Chrétien participated in the Soviet-French Soyuz T-6 mission in June 1982, becoming the first West European in space.[24] In 1978, Merbold, Nicollier and Ockels went to Houston for NASA training at Johnson Space Center while Malerba stayed in Europe.[25]

NASA first discussed the concept of having payload specialists aboard spaceflights in 1972,[26] and payload specialists were first used on Spacelab's initial flight.[27] Payload specialists did not have to meet the strict NASA requirements for mission specialists. The first Spacelab mission had been planned for 1980 or 1981 but was postponed until 1983; Nicollier and Ockels took advantage of this delay to complete mission specialist training. Merbold did not meet NASA's medical requirements due to a ureter stone he had in 1959,[28] and he remained a payload specialist.[29][30] Rather than training with NASA, Merbold started flight training for instrument rating at a flight school at Cologne Bonn Airport and worked with several organizations to prepare experiments for Spacelab.[31]

In 1982, the crew for the first Spacelab flight was finalized, with Merbold as primary ESA payload specialist and Ockels as his backup. NASA chose Byron K. Lichtenberg and his backup Michael Lampton.[32] The payload specialists started their training at Marshall Space Flight Center in August 1978, and then traveled to laboratories in several countries, where they learned the background of the planned experiments and how to operate the experimental equipment.[33] The mission specialists were Owen Garriott and Robert A. Parker, and the flight crew John Young and Brewster Shaw.[34] In January 1982, the mission and payload specialists started training at Marshall Space Flight Center on a Spacelab simulator. Some of the training took place at the German Aerospace Center in Cologne and at Kennedy Space Center.[35] While Merbold was made very welcome at Marshall, many of the staff at Johnson Space Center were opposed to payload specialists, and Merbold felt like an intruder there.[36] Although payload specialists were not supposed to train on the Northrop T-38 Talon jet, Young took Merbold on a flight and allowed him to fly the plane.[37]

STS-9 Space Shuttle mission

Merbold first flew to space on the STS-9 mission, which was also called Spacelab-1, aboard Space Shuttle Columbia.[38] The mission's launch was planned for 30 September 1983, but this was postponed because of issues with a communications satellite. A second launch date was set for 29 October 1983, but was again postponed after problems with the exhaust nozzle on the right solid rocket booster.[39] After repairs, the shuttle returned to the launch pad on 8 November 1983, and was launched from Kennedy Space Center Launch Complex 39A at 11:00 a.m. EST on 28 November 1983.[40][41] Merbold became the first non-US citizen to fly on a NASA space mission and also the first West German citizen in space.[42][43] The mission was the first six-person spaceflight.[38][44]

During the mission, the shuttle crew worked in groups of three in 12-hour shifts, with a "red team" consisting of Young, Parker and Merbold, and a "blue team" with the other three astronauts.[38] The "red team" worked from 9:00 p.m. to 9:00 a.m. EST.[45] Young usually worked on the flight deck, and Merbold and Parker in the Spacelab.[38] Merbold and Young became good friends.[46] On the mission's first day, approximately three hours after takeoff and after the orbiter's payload bay doors had been opened, the crew attempted to open the hatch leading to Spacelab.[47][48] At first, Garriott and Merbold could not open the jammed hatch; the entire crew took turns trying to open it without applying significant force, which might damage the door. They opened the hatch after 15 minutes.[48]

The Spacelab mission included about 70 experiments,[49] many of which involved fluids and materials in a microgravity environment.[50] The astronauts were subjects of a study on the effects of the environment in orbit on humans;[51] these included experiments aiming to understand space adaptation syndrome, of which three of the four scientific crew members displayed some symptoms.[52][53] Following NASA policy, it was not made public which astronaut had developed space sickness.[54] Merbold later commented he had vomited twice but felt much better afterwards.[55] Merbold repaired a faulty mirror heating facility, allowing some materials science experiments to continue.[56] The mission's success in gathering results, and the crew's low consumption of energy and cryogenic fuel, led to a one-day mission extension from nine days to ten.[57]

On one of the last days in orbit, Young, Lichtenberg and Merbold took part in an international, televised press conference that included US president Ronald Reagan in Washington, DC, and the Chancellor of Germany Helmut Kohl, who was at a European economic summit meeting in Athens, Greece.[58][59][60] During the telecast, which Reagan described as "one heck of a conference call", Merbold gave a tour of Spacelab and showed Europe from space while mentioning die Schönheit der Erde (the beauty of the Earth).[59][61] Merbold spoke to Kohl in German, and showed the shuttle's experiments to Kohl and Reagan, pointing out the possible importance of the materials-science experiments from Germany.[61]

When the crew prepared for the return to Earth, around five hours before the planned landing, two of the five onboard computers and one of three inertial measurement units malfunctioned, and the return was delayed by several orbits.[62] Columbia landed at Edwards Air Force Base (AFB) at 6:47 p.m. EST on 8 December 1983.[63] Just before the landing, a leak of hydrazine fuel caused a fire in the aft section.[64] After the return to Earth, Merbold compared the experience of standing up and walking again to walking on a ship rolling in a storm.[65] The four scientific crew members spent the week after landing doing extensive physiological experiments, many of them comparing their post-flight responses to those in microgravity.[66] After landing, Merbold was enthusiastic about the mission and the post-flight experiments.[67]

Ground-based astronaut work

In 1984, Ulf Merbold became the backup payload specialist for the Spacelab D-1 mission, which West Germany funded.[68][69] The mission, which was numbered STS-61-A, was carried out on the Space Shuttle Challenger from 30 October to 6 November 1985.[70] In ESA parlance, Merbold and the three other payload specialists—Germans Reinhard Furrer and Ernst Messerschmid and the Dutch Wubbo Ockels—were called "science astronauts" to distinguish them from "passengers" like Saudi prince Sultan bin Salman Al Saud and Utah senator Jake Garn, both of whom had also flown as payload specialists on the Space Shuttle.[71] During the Spacelab mission, Merbold acted as crew interface coordinator, working from the German Space Operations Center in Oberpfaffenhofen to support the astronauts on board while working with the scientists on the ground.[72]

From 1986, Merbold worked for ESA at the European Space Research and Technology Centre in Noordwijk, Netherlands, contributing to plans for what would become the Columbus module of the International Space Station (ISS).[1] In 1987, he became head of the German Aerospace Center's astronaut office, and in April–May 1993 he served as science coordinator for the second German Spacelab mission D-2 on STS-55.[1]

STS-42 Space Shuttle mission

In June 1989, Ulf Merbold was chosen to train as payload specialist for the International Microgravity Laboratory (IML-1) Spacelab mission.[73] STS-42 was intended to launch in December 1990 on Columbia but was delayed several times. After first being reassigned to launch with Atlantis in December 1991,[74] it finally launched on the Space Shuttle Discovery on 22 January 1992, with a final one-hour delay to 9:52 a.m. EST caused by bad weather and issues with a hydrogen pump.[75] The change from Columbia to Discovery meant the mission had to be shortened, as Columbia had been capable of carrying extra hydrogen and oxygen tanks that could power the fuel cells.[76] Merbold was the first astronaut to represent reunified Germany.[76] The other payload specialist on board was astronaut Roberta Bondar, the first Canadian woman in space.[76] Originally, Sonny Carter was assigned as one of three mission specialists, he died in a plane crash on 5 April 1991, and was replaced by David C. Hilmers.[77]

The mission specialized in experiments in life sciences and materials science in microgravity.[78] IML-1 included ESA's Biorack module,[79] a biological research facility in which cells and small organisms could be exposed to weightlessness and cosmic radiation.[80] It was used for microgravity experiments on various biological samples including frog eggs, fruit flies, and Physarum polycephalum slime molds. Bacteria, fungi and shrimp eggs were exposed to cosmic rays.[78] Other experiments focused on the human response to weightlessness or crystal growth.[81] There were also ten Getaway Special canisters with experiments on board.[82] Like STS-9, the mission operated in two teams who worked 12-hour shifts: a "blue team" consisting of mission commander Ronald J. Grabe together with Stephen S. Oswald, payload commander Norman Thagard, and Bondar; and a "red team" of William F. Readdy, Hilmers, and Merbold.[83] Because the crew did not use as many consumables as planned, the mission was extended from seven days to eight, landing at Edwards AFB on 30 January 1992, at 8:07 a.m. PST.[82]

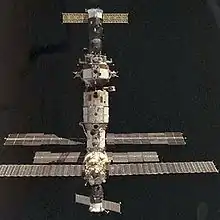

Euromir 94 mission

In November 1992, ESA decided to start cooperating with Russia on human spaceflight. The aim of this collaboration was to gain experience in long-duration spaceflights, which were not possible with NASA at the time,[84] and to prepare for the construction of the Columbus module of the ISS.[85][86] On 7 May 1993, Merbold and the Spanish astronaut Pedro Duque were chosen as candidates to serve as the ESA astronaut on the first Euromir mission, Euromir 94.[84]

Along with other potential Euromir 95 astronauts, German Thomas Reiter and Swedish Christer Fuglesang, in August 1993 Merbold and Duque began training at Yuri Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center in Star City, Russia, after completing preliminary training at the European Astronaut Centre, Cologne.[1][84] On 30 May 1994, it was announced Merbold would be the primary astronaut and Duque would serve as his backup.[84] Equipment with a mass of 140 kg (310 lb) for the mission was sent to Mir on the Progress M-24 transporter, which failed to dock and collided with Mir on 30 August 1994, successfully docking only under manual control from Mir on 2 September.[87]

Merbold launched with commander Aleksandr Viktorenko and flight engineer Yelena Kondakova on Soyuz TM-20 on 4 October 1994, 1:42 a.m. Moscow time.[88] Merbold became the second person to launch on both American and Russian spacecraft[84] after cosmonaut Sergei Krikalev, who had flown on Space Shuttle mission STS-60 in February 1994 after several Soviet and Russian spaceflights. During docking, the computer on board Soyuz TM-20 malfunctioned but Viktorenko managed to dock manually.[89] The cosmonauts then joined the existing Mir crew of Yuri Malenchenko, Talgat Musabayev and Valeri Polyakov,[84] expanding the crew to six people for 30 days.[88]

On board Mir, Merbold performed 23 life sciences experiments, 4 materials science experiments, and other experiments.[90] For one experiment designed to study the vestibular system, Merbold wore a helmet that recorded his motion and his eye movements.[91] On 11 October, a power loss disrupted some of these experiments[84] but power was restored after the station was reoriented to point the solar array toward the Sun.[90] The ground team rescheduled Merbold's experiments but a malfunction of a Czech-built materials processing furnace caused five of them to be postponed until after Merbold's return to Earth.[90] None of the experiments were damaged by the power outage.[92]

Merbold's return flight with Malenchenko and Musabayev on Soyuz TM-19 was delayed by one day to experiment with the automated docking system that had failed on the Progress transporter.[92] The test was successful and on 4 November, Soyuz TM-19 de-orbited, carrying the three cosmonauts and 16 kg (35 lb) of Merbold's samples from the biological experiments, with the remainder to return later on the Space Shuttle.[90] The STS-71 mission was also supposed to return a bag containing science videotapes created by Merbold but this bag was lost.[93] The landing of Soyuz TM-19 was rough; the cabin was blown off-course by nine kilometres (5.6 mi) and bounced after hitting the ground.[94][95] None of the crew were hurt during landing.[95]

During his three spaceflights—the most of any German national—Merbold has spent 49 days in space.[96]

Later career

In January 1995, shortly after the Euromir mission, Merbold became head of the astronaut department of the European Astronaut Centre in Cologne.[97] From 1999 to 2004, Merbold worked in the Microgravity Promotion Division of the ESA Directorate of Manned Spaceflight and Microgravity in Noordwijk,[1] where his task was to spread awareness of the opportunities provided by the ISS among European research and industry organizations. He retired on 30 July 2004, but has continued to do consulting work for ESA and give lectures.[97][98]

Personal life

.jpg.webp)

Since 1969,[99] Ulf Merbold has been married to Birgit, née Riester and the couple have two children, a daughter born in 1975 and a son born in 1979.[8] They live in Stuttgart.[99]

In 1984, Merbold met the East German cosmonaut Sigmund Jähn, who had become the first German in space after launching on Soyuz 31 on 26 August 1978. They both were born in the Vogtland (Jähn was born in Morgenröthe-Rautenkranz)[2] and grew up in East Germany.[76] Jähn and Merbold became founding members of the Association of Space Explorers in 1985.[100] Jähn helped Merbold's mother, who had moved to Stuttgart,[8] to obtain a permit for a vacation in East Germany. After German reunification, Merbold helped Jähn become a freelance consultant for the German Aerospace Center.[100] At the time of the Fall of the Berlin Wall, they were at an astronaut conference in Saudi Arabia together.[7]

In his spare time Merbold enjoys playing the piano and skiing. He also flies planes including gliders. Holding a commercial pilot license, he has over 3,000 hours of flight experience as a pilot.[1] On his 79th birthday, he inaugurated the new runway at the Flugplatz Greiz-Obergrochlitz airfield, landing with his wife in a Piper Seneca II.[101]

Awards and honors

In 1983, Merbold received the American Astronautical Society's Flight Achievement Award, together with the rest of the STS-9 crew.[1][102] He was also awarded the Order of Merit of Baden-Württemberg in December 1983.[103][104] In 1984, he was awarded the Haley Astronautics Award by the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics[105] and the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (first class).[1] In 1988, he was awarded the Order of Merit of North Rhine-Westphalia.[106] Merbold received the Russian Order of Friendship in November 1994,[107] the Kazakh Order of Parasat in January 1995[108] and the Russian Medal "For Merit in Space Exploration" in April 2011.[109] In 1995, he received an honorary doctorate in engineering from RWTH Aachen University.[110]

In 2008, the asteroid 10972 Merbold was named after him.[111][112]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Ulf Merbold". esa.int. 27 September 2004. Archived from the original on 17 March 2022. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- 1 2 "25 Years of Human Spaceflight in Europe". esa.int. 22 August 2003. Archived from the original on 29 September 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- 1 2 3 "Ulf Merbold – Munzinger Biographie". munzinger.de (in German). 17 May 2016. Archived from the original on 18 March 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ↑ Merbold 1988, p. 49.

- ↑ Wilkes 2019, p. 31.

- ↑ Ritscher, Bodo. "Totenbuch Sowjetisches Speziallager Nr. 2 Buchenwald". Gedenkstätte Buchenwald (in German). Archived from the original on 25 April 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- 1 2 Stirn, Alexander (17 May 2010). "Der Mann, der ins All wollte". Süddeutsche Zeitung (in German). ISSN 0174-4917. Archived from the original on 18 March 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 NASA 1983, p. 59.

- 1 2 Merbold 1988, p. 50.

- ↑ Schubert, Tobias (3 August 2022). "Ulf Merbold ist 500.000 wert". Thüringische Landeszeitung (in German). Gera. p. 15. OCLC 177309307. Archived from the original on 3 November 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022 – via PressReader.

- 1 2 3 4 Schwenke, Philipp (8 February 2012). "Eine Antwort, fünf Fragen". ZEIT ONLINE (in German). ISSN 0044-2070. Archived from the original on 18 March 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- 1 2 Wilkes 2019, p. 32.

- ↑ Merbold 1988, p. 56.

- ↑ Nestler, Ralf (10 April 2021). "Interview mit Ulf Merbold: "Dieser erste Blick aus dem Fenster"". Der Tagesspiegel Online (in German). ISSN 1865-2263. Archived from the original on 18 October 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- 1 2 Evans 2013, p. 208.

- ↑ Merbold 1988, p. 58.

- ↑ Merbold 1988, p. 169.

- ↑ Merbold 1976.

- ↑ Lord 1987, p. 20.

- ↑ Krige, Russo & Sebesta 2000, pp. 59–60.

- ↑ Lord 1987, p. 26.

- ↑ Froehlich 1983, p. 72.

- 1 2 Shapland & Rycroft 1984, p. 104.

- 1 2 Croft & Youskauskas 2019, p. 62.

- ↑ Chladek & Anderson 2017, pp. 252–253.

- ↑ Croft & Youskauskas 2019, p. 12.

- ↑ Froehlich 1983, p. 27.

- ↑ Merbold 1988, p. 261.

- ↑ Chladek & Anderson 2017, p. 257.

- ↑ Croft & Youskauskas 2019, p. 63.

- ↑ Merbold 1988, p. 262.

- ↑ Croft & Youskauskas 2019, p. 64.

- ↑ NASA 1983, p. 61.

- ↑ Chladek & Anderson 2017, pp. 257–258.

- ↑ NASA 1983, pp. 61–62.

- ↑ Croft & Youskauskas 2019, p. 40.

- ↑ Merbold, Ulf (22 August 2018). "Ulf Merbold: remembering John Young (1930–2018)". esa.int. Archived from the original on 14 September 2022. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 Evans 2005, p. 71.

- ↑ Evans 2005, pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Lord 1987, p. 345.

- ↑ Shapland & Rycroft 1984, pp. 116–117.

- ↑ NASA 1983, p. 2.

- ↑ "Ulf Merbold war der erste BRD-Astronaut". Frankfurter Rundschau (in German). 26 November 2008. ISSN 0940-6980. Archived from the original on 15 April 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ↑ Shayler & Burgess 2006, p. 377.

- ↑ Shayler & Burgess 2006, p. 378.

- ↑ Hitt & Smith 2014, p. 199.

- ↑ Lord 1987, p. 353.

- 1 2 Shayler & Burgess 2006, p. 380.

- ↑ Croft & Youskauskas 2019, p. 68.

- ↑ Evans 2005, p. 78.

- ↑ Evans 2005, pp. 79–80.

- ↑ Shayler & Burgess 2006, p. 384.

- ↑ Evans 2005, p. 80.

- ↑ Croft & Youskauskas 2019, p. 70.

- ↑ Croft & Youskauskas 2019, p. 72.

- ↑ Croft & Youskauskas 2019, p. 75.

- ↑ Shayler & Burgess 2006, p. 390.

- ↑ Shayler & Burgess 2006, p. 391.

- 1 2 Lord 1987, p. 358.

- ↑ Hitt & Smith 2014, p. 204.

- 1 2 O'Toole, Thomas; Hilts, Philip J. (6 December 1983). "Spacemen Talk to Leaders and Home Folks, on Two Continents". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ↑ Shayler & Burgess 2006, pp. 393–394.

- ↑ Lord 1987, p. 360.

- ↑ Shayler & Burgess 2006, p. 394.

- ↑ Croft & Youskauskas 2019, p. 78.

- ↑ Shayler & Burgess 2006, pp. 394–395.

- ↑ Croft & Youskauskas 2019, p. 73.

- ↑ Chladek & Anderson 2017, p. 267.

- ↑ Hitt & Smith 2014, pp. 215–216.

- ↑ Croft & Youskauskas 2019, p. 138.

- ↑ Croft & Youskauskas 2019, pp. 138–139.

- ↑ Croft & Youskauskas 2019, p. 153.

- ↑ Evans 2013, p. 203.

- ↑ Evans 2013, pp. 206–207.

- ↑ Evans 2013, p. 212.

- 1 2 3 4 Evans 2013, p. 207.

- ↑ Evans 2013, pp. 208–209.

- 1 2 Evans 2013, p. 213.

- ↑ Krige, Russo & Sebesta 2000, p. 602.

- ↑ Krige, Russo & Sebesta 2000, p. 167.

- ↑ Evans 2013, pp. 213–215.

- 1 2 Evans 2013, p. 216.

- ↑ Evans 2013, p. 211.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Vis 2000, p. 91.

- ↑ "DLR – German astronaut Ulf Merbold". DLRARTICLE DLR Portal. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ↑ "EUROMIR 94 heralds new era of cooperation in space". esa.int. 28 September 1994. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ↑ Evans 2013, p. 477.

- 1 2 Evans 2013, p. 478.

- ↑ Evans 2013, p. 479.

- 1 2 3 4 "EUROMIR 94". esa.int. Archived from the original on 23 March 2021. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ↑ Clery 1994, p. 25.

- 1 2 Evans 2013, p. 480.

- ↑ Vis 2000, p. 92.

- ↑ Harvey 1996, p. 368.

- 1 2 Hall & Shayler 2003, p. 349.

- ↑ "Ulf Merbold: STS-9 Payload Specialist". esa.int. Archived from the original on 1 April 2022. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- 1 2 "Biografie von Ulf Merbold". esa.int (in German). Archived from the original on 1 April 2022. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ↑ Hänel, Michael (16 September 2019). "Raumstationen: Ulf Merbold". planet-wissen.de (in German). Archived from the original on 29 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- 1 2 "Dr. Ulf Merbold: Physiker, Astronaut und Flieger" (PDF). Der Adler (in German). Vol. 77, no. 8. Stuttgart: Baden-Württembergischer Luftfahrtverband. 2021. p. 27. ISSN 0001-8279. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- 1 2 Hildebrandt, Antje (23 September 2019). "Sigmund Jähn – Held mit Rückenschmerzen". Cicero (in German). ISSN 1613-4826. Archived from the original on 16 April 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ↑ Freund, Christian (22 June 2020). "Astronaut weiht sanierte Start- und Landebahn ein – Willkommen in Greiz-Obergrochlitz". greiz-obergrochlitzer.de (in German). Archived from the original on 12 December 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ↑ "Neil Armstrong Space Flight Achievement Award". American Astronautical Society. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ↑ Merbold 1988, pp. 321–322.

- ↑ "Verdienstorden des Landes Baden-Württemberg" (PDF). Staatsministerium Baden-Württemberg (in German). Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ↑ "Haley Space Flight Award Recipients". aiaa.org. 4 January 2015. Archived from the original on 4 January 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ↑ "Verdienstorden des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen". land.nrw. Archived from the original on 29 August 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ↑ "Указ Президента Российской Федерации от 24.11.1994 г. № 2107". Президент России (in Russian). Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ↑ Первый Президент Республики Казахстан Нурсултан Назарбаев. Хроника деятельности. 1994–1995 годы (PDF) (in Russian). Astana: Деловой Мир Астана. 2011. p. 150. ISBN 978-601-7259-62-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ↑ "Указ Президента Российской Федерации от 12.04.2011 г. № 437". Президент России (in Russian). Archived from the original on 29 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ↑ "RWTH Aachen Honorary Doctors – RWTH AACHEN UNIVERSITY – English". rwth-aachen.de. Archived from the original on 28 August 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ↑ "IAU Minor Planet Center". minorplanetcenter.net. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ↑ "ESA gratuliert: Ulf Merbold und Thomas Reiter im All verewigt". esa.int (in German). 12 June 2008. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

Bibliography

- Chladek, Jay; Anderson, Clayton C. (2017). Outposts on the Frontier: A Fifty-Year History of Space Stations. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-1-4962-0108-9. OCLC 990337324. Archived from the original on 22 March 2022. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- Clery, Daniel (1994). "Euro-Russian Accord Begins with 30 Days of Solitude". Science. 266 (5182): 24–25. Bibcode:1994Sci...266...24C. doi:10.1126/science.7939639. ISSN 0036-8075. JSTOR 2884700. PMID 7939639.

- Croft, Melvin; Youskauskas, John (2019). Come Fly with Us: NASA's Payload Specialist Program. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-1-4962-1226-9. OCLC 1111904579. Archived from the original on 21 October 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- Evans, Ben (2005). Space Shuttle Columbia: Her Missions and Crews. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-21517-4. OCLC 61666197. Archived from the original on 29 October 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- Evans, Ben (4 October 2013). Partnership in Space: The Mid to Late Nineties. New York: Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4614-3278-4. OCLC 820780700. Archived from the original on 29 October 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- Froehlich, Walter (1983). Spacelab: an international short-stay orbiting laboratory. Washington, D.C.: National Aeronautics and Space Administration. OCLC 10202089.

- Hall, Rex; Shayler, David (7 May 2003). Soyuz: A Universal Spacecraft. New York: Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-85233-657-8. OCLC 50948699.

- Harvey, Brian (1996). The new Russian space programme : from competition to collaboration. Chichester; New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-96014-0.

- Hitt, David; Smith, Heather R. (2014). Bold They Rise: The Space Shuttle Early Years, 1972-1986. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-5548-7. OCLC 877032885. Archived from the original on 29 March 2022. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- Krige, John; Russo, Arturo; Sebesta, Lorenza (2000). A history of the European Space Agency 1958–1987 (PDF). Vol. II: The story of ESA, 1973–1987. Noordwijk: European Space Agency. ISBN 978-92-9092-536-1. OCLC 840364331. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 October 2021. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- Lord, Douglas R. (1987). Spacelab, an international success story. NASA SP ;487. Washington, DC: Scientific and Technical Information Division, National Aeronautics and Space Administration. OCLC 13946469. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- Merbold, Ulf (1976). Untersuchung der Strahlenschädigung von stickstoffdotierten Eisen nach Neutronenbestrahlung bei 140 Grad Celsius mit Hilfe von Restwiderstandsmessungen (Doctorate) (in German). University of Stuttgart. OCLC 310645878. 1075812429 (K10Plus number).

- Merbold, Ulf (1988). Flug ins All (in German). Bergisch Gladbach: Lübbe. ISBN 978-3-7857-0502-5. OCLC 74975325.

- NASA (1 November 1983). NASA Technical Reports Server (NTRS) 19840004146: STS-9 Spacelab 1 Press Kit (Report).

- Shapland, David; Rycroft, Michael J. (1984). Spacelab: research in earth orbit. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-26077-0.

- Shayler, David; Burgess, Colin (18 September 2006). NASA's Scientist-Astronauts. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-21897-7. OCLC 839215201. Archived from the original on 29 October 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- Vis, Bert (2000). "Russian with a foreign accent: non-Russian cosmonauts on Mir". The history of Mir, 1986–2000. London: British Interplanetary Society. ISBN 978-0-9506597-4-9. OCLC 1073580616.

- Wilkes, Johannes (14 August 2019). Unser schönes Thüringen (in German). Meßkirch: Gmeiner-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8392-6202-3. OCLC 1098794256. Archived from the original on 29 October 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2022.