| Union Army Balloon Corps | |

|---|---|

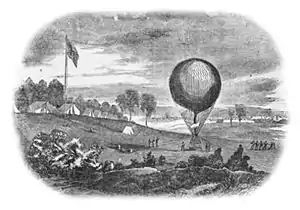

Woodblock sketch of Lowe's balloon with McClellan's Army of the Potomac as depicted in Harper's Weekly. | |

| Active | October 1861 – August 1863 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | Union |

| Branch | Army |

| Type | Aviation |

| Role | Aerial reconnaissance |

| Size | 8 aeronauts |

| Part of | Topographical Engineers (civilian contract) |

| Garrison/HQ | Fort Corcoran, Va. |

| Equipment | 7 aerostats with hydrogen gas generators |

| Engagements | Bull Run Yorktown Fair Oaks Vicksburg |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Thaddeus S. C. Lowe (Chief Aeronaut) |

The Union Army Balloon Corps was a branch of the Union Army during the American Civil War, established by presidential appointee Thaddeus S. C. Lowe. It was organized as a civilian operation, which employed a group of prominent American aeronauts and seven specially built, gas-filled balloons to perform aerial reconnaissance on the Confederate States Army.

Lowe was one of a few veteran balloonists who was working on an attempt to make a transatlantic crossing by balloon. His efforts were interrupted by the onset of the Civil War, which broke out one week before one of his most important test flights. Subsequently, he offered his aviation expertise to the development of an air-war mechanism through the use of aerostats for reconnaissance purposes. Lowe met with U.S. President Abraham Lincoln on 11 June 1861, and proposed a demonstration with his own balloon, the Enterprise, from the lawn of the armory directly across the street from the White House. From a height of 500 feet (150 m) he telegraphed a message to the President describing his view of the Washington, D.C., countryside. Eventually he was chosen over other candidates to be chief aeronaut of the newly formed Union Army Balloon Corps.

The Balloon Corps with a hand-selected team of expert aeronauts served at Yorktown, Seven Pines, Antietam, Fredericksburg, and other major battles of the Potomac River and the Virginia Peninsula. The Balloon Corps served the Union Army from October 1861 until the summer of 1863, when it was disbanded following the resignation of Lowe.

Selecting a Chief Aeronaut

The use of balloons as an air-war mechanism was first recorded in France by the French Aerostatic Corps at the Battle of Fleurus in 1794. U. S. President Abraham Lincoln became interested in an air-war mechanism for reconnaissance purposes. This created a notion at the War Department and at the Treasury that some sort of balloon aviation unit need be established and headed by a "Chief Aeronaut". Several top American balloonists traveled to Washington in hopes of obtaining just such a position. However, there were no proposed details to the establishment of such a unit, or whether it would even be a military or civilian operation. Nor was there any set method to the process of selecting a Chief Aeronaut, rather it became a free-for-all in attempts to attract the attention of any officials in either the government or the military. In actuality the use of balloons was left to the discretion of the commanding generals through a process of trial and error based on the best recommendations of the balloonists themselves. Of those seeking the position, only two were given actual opportunities to perform combat aerial reconnaissance, Prof. Thaddeus Lowe and Mr. John LaMountain.[1]

Thaddeus Lowe

Professor Thaddeus S. C. Lowe was one of the top American balloonists who sought the position of Chief Aeronaut for the Union Army.[2] Also vying for the position were Prof. John Wise, Prof. John LaMountain, and Ezra and James Allen. All these men were aeronauts of extraordinary qualification in aviation of the day. Among them Lowe stood out as the most successful in balloon building and the closest to making a transatlantic flight.[3] His scientific record was held in high regard among colleagues of the day, to include one Prof. Joseph Henry of the Smithsonian Institution, who became his greatest benefactor.[4]

On Henry's and others' recommendations, Lowe was contacted by Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase, who invited him to Washington for an audience with Secretary of War Simon Cameron and the President.[5] On 11 June 1861, Lowe was received by Lincoln and immediately offered to give the President a live demonstration with the balloon.[6]

On Saturday, 16 June, with his own balloon, the Enterprise, Lowe ascended some 500 feet (150 m) above the Columbian Armory with a telegraph key and operator, and a wire following a tether line to the White House across the street. From aloft he transmitted the message:

Balloon Enterprise

Washington, June 16 1861

To President United States:

This point of observation commands an area nearly fifty miles in diameter. The city with its girdle of encampments presents a superb scene. I have pleasure in sending you this first dispatch ever telegraphed from an aerial station and in acknowledging indebtedness to your encouragement for the opportunity of demonstrating the availability of the science of aeronautics in the service of the country. T.S.C. Lowe.[7][8]

Lowe's first assignment was with the Topographical Engineers, where his balloon was used for aerial observations and map making. Eventually he worked with Major General Irvin McDowell, who rode along with Lowe making preliminary observations over the battlefield at Bull Run. McDowell became impressed with Lowe and his balloon, and a good word reached the President, who personally introduced Lowe to Union General-in-Chief Winfield Scott. "General, this is my friend Professor Lowe who is organizing an aeronautics corps and who is to be its chief. I wish you would facilitate his work in every way." This introduction fairly well settled the selection of Lowe as Chief Aeronaut.[9] The details of establishing the corps and its method of operation were left up to Lowe. The misunderstanding that the Balloon Corps would remain a civilian contract lasted its duration, and neither Lowe nor any of his men ever received commissions.

John Wise

John Wise[10] was an early pioneer of American ballooning born in 1808. Although he made great contributions to the then newborn science of aeronautics, he was more a showman than a scientist. His attempts at free flight in preparation for a transatlantic crossing were less than successful, and he did not receive the same type of financial support from the patrons of the sciences, nor did he carry the overall scientific credibility of Lowe.

Wise was, however, taken seriously enough by the Topographical Engineers to be asked to build a balloon. Mary Hoehling indicated that Captain Whipple of the Topographical Engineers told Lowe that Wise was preparing to bring up his own balloon, supposedly the Atlantic. Other accounts state that John LaMountain had taken possession of the Atlantic after a failed flight he made with Wise in 1859, and later place the Atlantic with LaMountain at Fort Monroe. Lowe's report says that Captain Whipple indicated they had instructed Mr. Wise to construct a new balloon. He also proposed that Lowe pilot the new balloon. Prof. Lowe was vehemently opposed to flying one of Wise's old-style balloons.

The engineers waited the whole month of July for Wise to arrive on scene. By 19 July 1861, McDowell started calling for a balloon to be brought to the front at First Bull Run (Centreville). As Wise was not to be found, Whipple sent Lowe out to inflate his balloon and prepare to set out for Falls Church. Mary Hoehling tells of the sudden appearance of John Wise who demanded that Lowe stop his inflating of the Enterprise and let him inflate his balloon instead. Wise had legal papers upholding his purported authority. Although Wise's arrival on the scene was tardy, he did inflate his balloon and proceeded toward the battlefield. On the way the balloon became caught in the brush and was permanently disabled. This ended Wise's bid for the position, and Lowe was at last unencumbered from taking up the task.

Lowe describes the inflation incident in his official report less dramatically, saying that he was told by the gas plant supervisor to disconnect and let another balloon go first. Lowe did not name names, but it is not likely that it was anyone other than Wise. Lowe's report about a new balloon has to be considered over Hoehling's account of the Atlantic.[11]

John LaMountain

John LaMountain,[10] born in 1830, had accrued quite a reputation in the field of aeronautics. He had joined company with Wise at one time to help with the plans for a transatlantic flight. Their attempt failed miserably, wrecked their balloon, the Atlantic, and ended their partnership. LaMountain took possession of the balloon.

LaMountain's contributions and successes were minimal. However, he did attract the attention of General Benjamin Butler at Fort Monroe. LaMountain operated at Fort Monroe for a while with the battered Atlantic and was actually accredited with having made the first effective wartime observations from an aerial position. He also obtained use of a balloon, the Saratoga, which he soon lost in a windstorm. LaMountain advocated free flight balloon reconnaissance, whereas Lowe used captive or tethered flight, remaining always attached to a ground crew who could reel him in.

Wise and LaMountain had been longtime detractors of Prof. Lowe, but LaMountain maintained a vitriolic campaign against Lowe to discredit him and usurp his position as Chief Aeronaut. He used the arena of public opinion to revile Lowe. But as Gen. Butler was replaced at Fort Monroe, LaMountain was assigned to the Balloon Corps under Lowe's command. LaMountain continued his public derogation of Lowe as well as creating ill-will among the other men in the Corps. Lowe lodged a formal complaint to Gen. George B. McClellan, and by February 1862 LaMountain was discharged from military service.[12]

Free flight vs. captive flight

There were two methods of piloting balloons: free flight or captive. Free flight meant that the balloon was able to travel in any direction or distance for as long or as far as the pilot was able to fly it. Captive flight meant that the balloon was retained by a tether or series of tethers manned by ground crews. Free flight required that the pilot ascend and return by his own control. Captive flight used ground crews to assist in altitude control and speedy return to the exact starting point. Tethers also allowed for the stringing of telegraph wires back to the ground. Information gathered from balloon observation was relayed to the ground by various means of signaling. From high altitudes the telegraph was almost always necessary. At closer altitudes a series of prepared flag signals, hand signals, or even a megaphone could be used to communicate with the ground. At night either the telegraph or lamps could be used. In the later battles of Lowe's tenure, all reports and communications were ordered to be made orally by ascending and descending with the balloon. This is notable in Lowe's Official Report II to the Secretary where his usual transcriptions of messages were lacking. Free flight would almost always require the aeronaut to return and make a report. This would be an obvious detriment to timely reporting.

LaMountain and Lowe had long argued over free flight and captive flight. In Lowe's first instance of demonstration at Bull Run, he made a free flight which caught him hovering over Union encampments who could not properly identify him. As a civilian he wore no uniform nor insignias. With each descent came the threat of being fired on, and to make each descent Lowe needed to release gas. In one instance Lowe was forced to land behind enemy lines and await being rescued overnight. After this incident he remained tethered to the ground by which he could be reeled in at a moment's notice. Besides, his use of the telegraph from the balloon car required a wire be run along the tether.[13]

LaMountain, from his position at Fort Monroe, had the luxury of flying free. When he was enjoined with the Balloon Corps, he began insisting that his reconnaissance flights be made free. Lowe strictly instructed his men against free flight as a matter of policy and procedure. Eventually the two men agreed to a showdown in which LaMountain made one of his free flights. The flight was a success as a reconnaissance flight with LaMountain being able to go where he would. But on his return he was threatened by Union troops who could not identify him. His balloon was shot down, and LaMountain was treated harshly until he was clearly identified.[14]

Lowe considered the incident an argument against free flight. LaMountain insisted that the flight was highly successful despite the unfortunate incident. The showdown did nothing to settle the argument, but Lowe's position as Chief Aeronaut allowed him to prevail.[15]

Building military balloons

Lowe believed that balloons used for military purposes had to be better constructed than the common balloons used by civilian aeronauts. They also required special handling and care for use on the battlefield. At first the balloons of the day were inflated at municipal coke gas supply stations and were towed inflated by ground crews to the field. Lowe recognized the need for the development of portable hydrogen gas generators, by which the balloons could be filled in the field. Lowe had to deal with administrative officers who usually held ranks lower than major and had more interest in accounting than providing for a proper war effort. This caused delays in the funding of materials.

Lowe was called out for another demonstration mission that would change the effective use of field artillery. On 24 September 1861, he was directed to position himself at Fort Corcoran, south of Washington, to ascend and overlook the Confederate encampments at Falls Church, Virginia, at a distance further south. A concealed Union artillery battery was remotely located at Camp Advance. Lowe was to give flag signal directions to the artillery, who would fire blindly on Falls Church. Each signal would indicate adjustments to the left, to the right, long or short. Simultaneously reports were telegraphed down to headquarters at the fort. With only a few corrections, the battery was soon landing rounds right on target. This was the precursor to the use of the artillery forward observer (FO).[16]

The next day, Lowe received orders to build four proper balloons with hydrogen gas generators.[17] Lowe went to work at his Philadelphia facility. He was given funding to order India silk and cotton cording he had proposed for their construction. Along with that came Lowe's undisclosed recipe for a varnish that would render the balloon envelopes leakproof.[18]

The generators were built at the Washington Navy Yard by master joiners who fashioned a contraption of copper plumbing and tanks which, when filled with sulfuric acid and iron filings, would yield hydrogen gas. The generators were Lowe's own design and were considered a marvel of engineering.[19] They were designed to be loaded into box crates that could easily fit on a standard buckboard. The generators took more time to build than the balloons and were not as readily available as the first balloon.

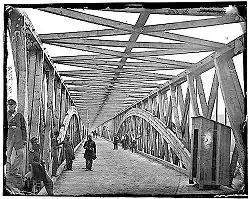

By 1 October 1861, the first balloon, the Union, was ready for action. Though it lacked a portable gas generator, it was called into immediate service.[20] It was gassed up in Washington and towed overnight to Lewinsville via Chain Bridge. The fully covered and trellised bridge required that the towing handlers crawl over the bridge beams and stringers to cross the upper Potomac River into Fairfax County. The balloon and crew arrived by daylight, exhausted from the nine-hour overnight ordeal, when a gale-force wind took the balloon away. It was later recovered, but not before Lowe, who was humiliated by the incident, went on a tirade about the delays in providing proper equipment.[21]

Lowe built seven balloons, six of which were put into service. Each balloon was accompanied by two gas generating sets. The smaller balloons were used in windier weather, or for quick, one-man, low altitude ascents. They inflated quickly since they required less gas. They were:

- Eagle

- Constitution

- Washington

The larger balloons were used for carrying more weight, such as a telegraph key set and an additional man as an operator. They could also ascend higher. They were:

- Union

- Intrepid (Lowe's favorite balloon)

- Excelsior

- United States

The latter two balloons were held in storage in a Washington warehouse. Eventually the Excelsior was sent to Camp Lowe,[22] a high altitude observation point, as a back-up balloon to the Intrepid during harsh winter weather, but the United States was never put into service. LaMountain made reference to these two balloons in his diatribes against Lowe as "being hoarded" by Lowe so he could buy them unused at the end of the war.[23]

Establishing the Corps

Initially, Lowe was offered $30 per day for each day his balloon was in use. Lowe offered to accept $10 gold per day (colonel's pay) if he were to be allowed to build more suitable balloons.[24] He was also allowed to hire as many men as he needed for $3 currency per day.[25] Lowe was able to enlist his father, Clovis Lowe, an accomplished balloonist; Captain Dickinson, a seafaring volunteer from his days of transatlantic attempts; the Allen brothers, who had lost their own balloon when they were vying for the top job; two men the Allen brothers recommended, Eben Seaver and J. B. Starkweather; William Paullin, an older Philadelphia colleague; German balloonist John Steiner; and Ebenezer Mason, Lowe's construction supervisor, who requested active duty.[26]

Lowe set up several locations for the balloons—Fort Monroe, Washington D.C., Camp Lowe near Harpers Ferry—but always kept himself at the battle front. He served General McClellan at Yorktown until the Confederates retreated toward Richmond. The heavily forested Virginia Peninsula forced him to take to the waterways.[27] Balloon service was requested at more remote locations as well. Eben Seaver was assigned to take the Eagle to the Mississippi River to assist in battlefronts there. Mr. Starkweather was sent to Port Royal with the Washington just prior to the Peninsula Campaign.

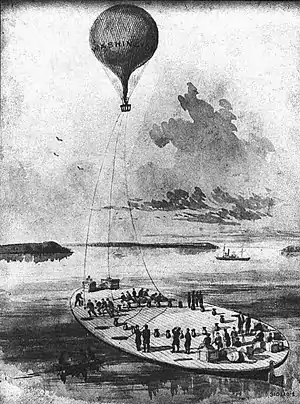

First aircraft carrier

The General Washington Parke Custis, a converted coal barge, had its deck cleared of all items that could entangle the ropes and nets of the balloons, and it was used as a river transport for the Corps.[28] Lowe had two gas generators and a balloon loaded aboard and later reported:

I have the pleasure of reporting the complete success of the first balloon expedition by water ever attempted. I left the Navy yard early Sunday morning ... having on board competent assistant aeronauts, together with my new gas generating apparatus, which, though used for the first time, worked admirably.[29]

Peninsula Campaign

The battlefront turned toward Richmond in the Peninsula Campaign. The heavy forestation inhibited the use of balloons, so Lowe and his Balloon Corps, with the use of three of his balloons, the Constitution, the Washington, and the larger Intrepid,[30] used the waterways to make its way inland. In mid May 1862, Lowe arrived at the White House on the Pamunkey River.[31] This is the first home of George and Martha Washington, after which the Washington presidential residence is named. At this time, it was the home of the son of Robert E. Lee, whose family fled at the arrival of Lowe.[32] Lowe was met by McClellan's Army a few days later, and by 18 May, he had set up a balloon camp at Gaines' Farm across the Chickahominy River north of Richmond, and another at Mechanicsville. From these vantage points, Lowe, his assistant James Allen, and his father Clovis were able to overlook the Battle of Seven Pines.[33]

A small contingent from Gen. Samuel P. Heintzelman's corps crossed the river toward Richmond and was slowly being surrounded by elements of the Confederate Army. McClellan felt that the Confederates were simply feigning an attack. Lowe could see, from his better vantage point, that they were converging on Heintzelman's position. Heintzelman was cut off from the main body because the swollen river had taken out all the bridges. Lowe sent urgent word of Heintzelman's predicament and recommended immediate repair of New Bridge and reinforcements for him.[34]

At the same time, he sent over an order for the inflation of the Intrepid, a larger balloon that could take him higher with telegraph equipment, in order to oversee the imminent battle. When Lowe arrived from Mechanicsville to the site of the Intrepid at Gaines' Mill, he saw that the aerostat's envelope was an hour away from being fully inflated. He then called for a camp kettle to have the bottom cut out of it, and he hooked the valve ends of the Intrepid and the Constitution together. He had the gas of the Constitution transferred to the Intrepid and was up in the air in 15 minutes.[35] From this new vantage point, Lowe was able to report on all the Confederate movements. McClellan took Lowe's advice, repaired the bridge, and had reinforcements sent to Heintzelman's aid. An account of the battle was being witnessed by the visiting Count de Joinville who at day's end addressed Lowe with: "You, sir, have saved the day!"[36][37]

Confederate Army's counter

Because of the effectiveness of the Union Army Balloon Corps, the Confederates felt compelled to incorporate balloons as well.[38] Since coke gas was not readily available in Richmond, the first balloons were made of the Montgolfier rigid style: cotton stretched over wood framing and filled with hot smoke from fires made of oil-soaked pine cones. They were piloted by Captain John R. Bryan for use at Yorktown. Bryan's handlers were poorly experienced, and his balloon began spinning in the air. In another incident, one of the handlers became entangled in the ascending tether rope which had to be chopped loose, leaving the captain free-flying over his own Confederate positions whose troops threatened to shoot him down.

Attempts at making gas-filled silk balloons were hampered by the South's inability to obtain any imports. They did fashion a balloon from dress silk.[39] Evans cites excerpts from Confederate letters that stated their balloons were made from dress-making silk and not dresses themselves. As it was put: "... not a single Southern Belle was asked to give up her Sunday best for the cause." Eugene Block quotes a letter that Lowe received from Confederate Major General James Longstreet asserting that they were sent out to gather up all the silk dresses to be found to fashion a balloon:

While we were longing for balloons that poverty denied us, a genius arose and suggested that we send out and get every silk dress in the Confederacy to make a balloon. It was done and soon we had a great patchwork ship ... for use in the Seven Days campaign. One day it was on a steamer down the James River when the tide went out and left it high and dry on a [sand]bar. The Federals gathered it in, and with it the last silk dress in the Confederacy. This was the meanest trick of the war ...

The silk material balloon used by the Confederates was of a design by Dr. Edward Cheves of Savannah, Georgia. Cheves had the silk material sewn together by seamstresses and then covered the silk material with a varnish made by melting rubber in oil. The balloon was filled with a coal gas and launched from a railroad car that its pilot, Edward Porter Alexander, had positioned near the battlefield. In late June 1862, Alexander made a few ascents in the balloon and was able to signal his observations of the battlefield to men on the ground using a wigwag system that he had devised. The coal gas used in the balloon was only able to keep the balloon aloft for about three to four hours at a time.[40]

The patchwork silk was given to Lowe, who had no use for it but to cut it up and distribute it to Congress as souvenirs. The inflated spheres appeared as multi-colored orbs over Richmond[41] and were piloted by Captain Landon Cheeves. The balloon was loaded onto a primitive form of an aircraft carrier, the CSS Teaser. Before the first balloon could be used, it was captured by the crew of the USS Maratanza during transportation on the James River. A second balloon was put into action in the summer of 1863, when it was blown from its mooring and taken by Union forces and divided up as souvenirs for members of the Federal Congress.[42] As the Union Army reduced its use of balloons, so did the Confederates.

Troubled Balloon Corps

During the Seven Days Battles in late June, McClellan's army was forced to retreat from the outskirts of Richmond. Lowe returned to Washington and he contracted malaria in the swampy conditions and was out of service for a little more than a month.[43] When he returned to duty, he found that all his wagons, mules, and service equipment had been returned to the Army Quartermaster. He was essentially out of a job. Lowe was ordered to join the Army for the Battle of Antietam, but he did not reach the battlefield until after the Confederates began their retreat to Virginia. Lowe had to reintroduce himself to the new commanding general of the Army of the Potomac, Ambrose Burnside, who activated Lowe at the Battle of Fredericksburg.[44]

For all its success, the Balloon Corps was never fully appreciated by the military community. The ballonists were still regarded as carnival showmen. Others had little respect for their break-neck operation. The only ones who found any value in them were the generals whose jobs and reputations were on the line. Lower-ranking administrators looked with disdain on this band of civilians who, as they perceived them, had no place in the military. Furthermore, none of the corps ever received a military commission, leaving them facing the dangers of being captured and treated as spies, summarily punishable by death.

The Balloon Corps was eventually assigned to the Army Corps of Engineers and put under the administrative purview of one Captain Cyrus B. Comstock, who did not appreciate a civilian (Lowe) being paid more than he. He reduced Lowe's pay from $10 gold to $6 currency (equal to $3 gold) per day. Lowe posted a letter of outrage and threatened to resign his position. No one came to his support, and Comstock remained unyielding. On 8 April 1863, Lowe left the military service and returned to the private sector.[45][46][47] Direction of the Balloon Corps defaulted to the Allen brothers, but they were not as competent as Lowe.[48] By 1 August 1863, the Corps was no longer used.

After the Civil War

Manned air-war mechanisms became important again to the Army when the airship (a dirigible, blimp, or zeppelin) came into existence with their motorized propulsion and mechanical means of steering. The United States Army Signal Corps established a War Balloon Company in 1893 at Fort Riley, Kansas (at the time, home of the Signal School), and the next year at Fort Logan, Colorado, using a single balloon (the General Myer) purchased in France. When that balloon deteriorated, members of the company sewed together a silk replacement in 1897. The balloon, dubbed the Santiago, saw limited use in combat in 1898 during the Spanish–American War.[49]

Reports of Lowe's work in aeronautics and aerial reconnaissance were heard abroad. In 1864, Lowe was offered a Major-General position with the Brazilian Army, which was at war with Paraguay, but he turned it down.

In the 19th century, the idea of dropping ordnance on the enemy from an aerial station was not seriously considered, although there was a patent issued to a Charles Perley in February 1863 for a bomb-dropping device that could be floated aloft by balloon. The balloon bomb was to be unmanned, and the plan was a theory which had no effective way of assuring that a bomb could be delivered and dropped remotely on the enemy. Also, as a civilian operation the Balloon Corps would have never been expected to drop ordnance.[50]

See also

Notes and references

- ↑ Lowe spent a week in Washington awaiting an audience with the President all the while demonstrating the use of his balloon to anyone who would give him attention.

- ↑ Note the title "professor" was given to men of pioneering expertise in the sciences, usually by the newspapers. Such a title would be widely accepted throughout the scientific community without particular regard to academia. Becoming Chief Aeronaut was not a primary career choice for Lowe, but his undaunted patriotism directed him to provide his services to the Union in this time of emergency.

- ↑ Hoehling, One Man Air Corps, chs 5 & 6. Lowe's preparation of a large balloon for a transatlantic crossing.

- ↑ Block, Above the Civil War, p. 34. A great deal of Lowe's support came from Prof. Henry, but there were many other influential friends who would influence Cabinet officials into accepting Lowe. Among these were several newspaper editors who also followed Lowe's scientific exploits. Many newspaper editors were very influential due to their contact with the public.

- ↑ Hoehling, p. 87.

- ↑ Hoehling, p. 91.

- ↑ Hoehling, p. 94. A photographic copy of this telegram shows a hand date of 16 June which corrects historical accounts of 17 June which was a Sunday.

- ↑ "Thaddeus S. C. Lowe to Abraham Lincoln, Sunday, June 16, 1861. Telegram from a balloon". From the "Abraham Lincoln Papers" .Library of Congress, Manuscript Division. Retrieved 26 July 2011

- ↑ Hoehling, p.111. This was the last time Lowe saw Lincoln; Lowe's fate was in the hands of the military.

- 1 2 Centennial of flight Archived 21 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ The whole incident is sorted and restated in Mike Manning's Intrepid, An Account of Prof. T.S.C. Lowe, Civil War Aeronaut and Hero on p. 25.

- ↑ Block, Above the Civil War, pp. 100–101.

- ↑ Hoehling, pp. 104–108

- ↑ Block, Above the Civil War, pp.98–99.

- ↑ Block, p. 100

- ↑ Hoehling, pp. 116–117.

- ↑ Hoehling, p. 118.

- ↑ Hoehling, p. 46. Lowe's secret varnish recipe was possibly the one part of his balloon building that made him so successful.

- ↑ Hoehling, p. 120.

- ↑ Hoehling, p. 122.

- ↑ Hoehling, p. 123.

- ↑ Camp Lowe was the first of anything to be named for Thaddeus Lowe. Because of the altitude and subsequent snow and ice, the balloons at Camp Lowe had to be re-varnished more often.

- ↑ Block, p. 99.

- ↑ Hoehling, p. 111.

- ↑ Hoehling, p. 121.

- ↑ Hoehling, ch. 13.

- ↑ Hoehling, ch 13.

- ↑ Hoehling, p. 124.

- ↑ Lowe's Official Report Part I.

- ↑ The Constitution was called in from Fort Monroe. The Washington returned from Port Royal just in time for the Peninsula Campaign, while Starkweather retired to Washington, D.C. The Intrepid was called in from Camp Lowe.

- ↑ Hoehling, p. 144. Lowe was assigned a First Sergeant and a wagon master to assist in troop movements and bivouac.

- ↑ Hoehling, p. 144.

- ↑ Hoehling, p. 148.

- ↑ Hoehling, p. 151–152.

- ↑ Hoehling, p. 153. Lowe's quick action was later valued at "a million dollars a minute."

- ↑ Hoehling, p. 155.

- ↑ Lowe's Official Report Part II. Lowe noted de Joinville's remarks in his own report as a matter of rebuttal against some of the demeaning comments that had been made about him and the Balloon Corps.

- ↑ Centennial of flight Archived 25 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Evans, Air War over Virginia vs. Block, Above the Civil War

- ↑ Michael R. Bradley, It Happened in the Civil War (2002; rev. 2010) pp. 22.

- ↑ Hoehling, p. 164

- ↑ Block, p. 96.

- ↑ The swampy conditions around Richmond caused a great deal of illness among the Union troops. Lowe's First Sergeant died of typhoid fever.

- ↑ Block, p. 101. Lowe had put his balloon in position on the Fredericksburg battlefield, but Burnside decided to hold off on ascending.

- ↑ Block, p. 101

- ↑ Hoehling, pp. 168–169.

- ↑ Actually Lowe left the service in May, but he was paid through 8 April.

- ↑ The Allen brothers were not recognized as Chief Aeronauts as the military recognition of the Balloon Corps deteriorated, nor were they actually assigned the duty; they were merely next in line.

- ↑ Raines, Rebecca Robbins, Getting the Message Through: A Branch History of the U.S. Army Signal Corps, Army Historical Series, Center of Military History, United States Army, 1996, ISBN 0-16-045351-8

- ↑ Balloon Bombs Archived 22 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine

Bibliography

- Block, Eugene B., Above the Civil War, Howell-North Book, Berkeley, Ca., 1966. Library of Congress CC# 66-15640.

- Evans, Charles M., "Air War over Virginia", Civil War Times, October 1996.

- Evans, Charles M., The War of the Aeronauts—A History of Ballooning During the Civil War, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2002.

- Haydon, F. Stansbury, Military Ballooning during the Early Civil War, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000 ISBN 9780801864421

- Hoehling, Mary, Thaddeus Lowe, America's One-Man Air Corps, Julian Messner, Inc., New York, N. Y., 1958. Library of Congress CC# 58-7260.

- Lowe, Thaddeus, Official Report (to the Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton) (Parts I & II) (#11 & #12) O.R. - Series III - Volume III [S#124] Correspondence, Orders, Reports, and Returns of the Union Authorities From 1 January to 31 December 1863.

- Manning, Mike, Intrepid, An Account of Prof. T.S.C. Lowe, Civil War Aeronaut and Hero, self-published 2005.

- Poleskie, Stephen, The Balloonist: The Story of T. S. C. Lowe—Inventor, Scientist, Magician, and Father of the U.S. Air Force, Frederic C. Beil, 2007.

- Seims, Charles, Mount Lowe, The Railway in the Clouds, Golden West Books, San Marino, California, 1976. ISBN 0-87095-075-4.