Alternative legal systems began to be used by Irish nationalist organizations during the 1760s as a means of opposing British rule in Ireland. Groups which enforced different laws included the Whiteboys, Repeal Association, Ribbonmen, Irish National Land League, Irish National League, United Irish League, Sinn Féin, and the Irish Republic during the Irish War of Independence. These alternative justice systems were connected to the agrarian protest movements which sponsored them and filled the gap left by the official authority, which never had the popular support or legitimacy which it needed to govern effectively. Opponents of British rule in Ireland sought to create an alternative system, based on Irish (rather than English) law, which would eventually supplant British authority.

Background

British law, a chief means of enforcing British rule in Ireland,[1] was viewed as a foreign imposition rather than a legitimate authority.[2] From the Anglo-Norman invasion to the beginning of the seventeenth century, common law coexisted with the indigenous Brehon law. The former predominated in English-controlled areas, and the latter in other regions; in some places, both systems coexisted.[3][4] The law was written and court proceedings were held in English, at a time when Irish was the sole language of most Irish people.[4][5] During the sixteenth century, the surrender and regrant system was intended to co-opt Gaelic chieftains and replace Gaelic customs with English property law. The Penal Laws restricted the civil rights of Catholics until they were repealed during the 1830s.[1] British land law enforced the property rights of landowners, ignoring Irish customs such as tenant-right.[6] The magistrates' courts were run by unpaid landlords and other members of the Protestant Ascendancy, rather than salaried civil servants.[7] Trust in the judicial system was further eroded by the wrongful conviction and execution of Maolra Seoighe, a monolingual Irish speaker who could not understand the court proceedings, for the 1882 Maamtrasna murders.[8] The British government never had the support or legitimacy it needed to effectively govern Ireland, which led to the emergence of alternative systems to fill that gap.[9]

Unwritten law

Before the conquest the Irish people knew nothing of absolute property in land. The land virtually belonged to the entire sept, the chief was little more than the managing member of the association. The feudal idea, which views all rights as emanating from a head landlord, came in with the conquest, was associated with foreign dominion, and has never to this day been recognized by the moral sentiments of the people ... In the moral feelings of the Irish people, the right to hold the land goes, as it did in the beginning, with the right to till it.

John Stuart Mill, as quoted by Michael Davitt at the first meeting of the Land War[10]

The "unwritten law" or "unwritten agrarian code"[11] was a deep-rooted idea among Irish smallholders that access to land for subsistence farming was a human right which superseded property rights and, regardless of titular ownership, the right to use land was hereditary and not based on the ability to pay rent.[12] This concept had parallels in Brehon law, which did not recognize absolute property rights. Even a lord's demesne technically belonged to his entire sept.[13] It was based on the idea that the land of Ireland rightfully belonged to the Irish people, but had been stolen by English invaders who claimed it by the right of conquest. Therefore, Irish tenants viewed the landlord–tenant relationship as inherently illegitimate and sought to abolish it. In the code's early version, practiced by the Whiteboys secret society beginning in the 1760s, it had a reactionary character which looked back to an era when there had supposedly been a reciprocal relationship between landlords and tenants. Later versions were friendly to capitalism, advocating a market economy in land and agricultural products without the "alien" landlord class.[14]

The idea of "unwritten law" was expressed and refined by the Young Ireland activist James Fintan Lalor (1807–1849), who insisted that the Irish people had allodial title to their own land. Lalor believed that a farmer had the first right to his crop for subsistence and seed, and only then could other claims be made on the harvest. Instead of landlords evicting tenants, Lalor preferred that the landlords—"strangers here and strangers everywhere, owning no country and owned by none"—be served with a writ of ejectment.[15] Lalor advised the Irish people to refuse "obedience to usurped authority" and resist English law, instead setting up their own government and "refus[ing] ALL rent to the present usurping proprietors".[16] Lalor's writings were the basis of the agrarian code enforced by the Irish National Land League during the Land War in the 1880s.[17] The tenets of the unwritten law appeared in "speeches, resolutions, placards, boycotts ... threatening letters and acts of outrage".[18]

Secret societies

The Whiteboys were oath-bound secret societies in rural Ireland since the 1760s.[19] The Threshers originated in County Mayo early in the nineteenth century and emphasized economic issues; its code regulated prices (including the price of potatoes), and demanded the reduction of the Church of Ireland's tithes and the Catholic Church's fees.[20] Ribbon societies were first organized by poor Catholics during the 1810s. They began in northern Ireland to combat the Protestant Orange Order, but later expanded into agrarian agitation and spread southward.[21][22] The Molly Maguires, who appeared in the 1840s, were often confused with Ribbonmen. Whiteboys and Ribbonism became synonymous with agrarian violence in general, and the secret societies which practiced it.[19] The secret societies tended to pop up during agricultural depressions, and vanish in good economic times.[23]

According to American historian Kevin Kenny, the alternative law as understood by the rural poor is the most convincing explanation for the violence practiced by these societies. Rather than a civil war by the Irish against a supposedly alien landlord class, the violence was understood as retributive justice for violations of traditional landholding and land-use practices.[24] The rural poor could be targets if they broke their oaths to the society or otherwise failed to act in solidarity with the unwritten law.[25] Punishments ranged from digging up new pasture land in an effort to free it up for potato cultivation, tearing down fences on newly-enclosed areas, mutilating or killing livestock, to threats and attacks on landlords' agents and merchants judged to charge exorbitant prices. Murders occurred, but were rare.[26][27]

Although these societies did not systematically enforce their version of the law via a court system,[28] a person accused of violating the code could be tried by their local society in absentia.[29] According to Sir Thomas Larcom, "There are in fact two codes of law in force and in antagonism—one the statute law enforced by judges and jurors, in which the people do not yet trust—the other a secret law, enforced by themselves—its agents the Ribbonmen and the bullet."[30]

Repeal Association

In July 1843, Daniel O'Connell announced that his mass-membership Repeal Association (for the repeal of the Acts of Union 1800) would set up a court system as part of its plan to create an Irish government. The courts would be staffed by magistrates who had been dismissed for their pro-Repeal opinions, and supplemented by individuals nominated by Repeal clergy and Repeal Wardens. John Gray, owner of the Freeman's Journal, drew up a detailed plan for a national court system based on existing districts; three or more arbiters would adjudicate cases, based on a majority vote. No court fees would be charged, and those who agreed to attend the court would be dismissed from the Repeal Association if they did not obey a verdict. After arbiters were appointed, the courts began to function by the end of October 1843. Their popularity threatened British rule in Ireland;[31] O'Connell was arrested and charged with three counts of conspiracy in connection with the tribunals.[32]

The Repeal Association crumbled after the Great Famine (1845–1849), and the Ribbon Societies assumed its role as arbiters of land and wage disputes. Other arbitration courts were organized by local priests, who denied sacraments to those who did not observe a verdict. Contemporary Conservative commentators said that the societies were an alternative justice system; their activities were legal, as long as they did not compel attendance.[33]

Irish Republican Brotherhood

After the unsuccessful 1867 Fenian Rising, the Irish Republican Brotherhood (a physical-force Irish republican group) formed a supreme council. Considering their "Irish Republic" the country's only legitimate authority, they passed a number of constitutions and laws. Violations were punished, and accused traitors were executed.[34]

Land League

The Irish National Land League (1879–1882) was a nationally organized agrarian protest society which sought fair rent, free sale, and fixity of tenure for small farmers and, ultimately, peasant ownership of the land they worked.[35][36] Some of its local branches established arbitration courts in 1880 and 1881. Cases were typically heard by the executive committee, which would summon both parties, call witnesses, examine evidence presented by the parties, make a judgment and assign a penalty for violations of the code. Juries would sometimes be called from local communities, and the plaintiff was occasionally the prosecutor.[37][38] The courts were modeled on British courts and, according to Western News, the Athenry Land League court docket exceeded that of its competing British court.[39] American historian Donald Jordan emphasizes that despite their common-law trappings, the tribunals were essentially an extension of the local Land League branch and adjudicated violations of its own rules.[29] The courts were described as a "shadow legal system" by British academic Frank Ledwidge.[36] According to historian Charles Townshend, the formation of courts was the "most unacceptable of all acts of defiance" committed by the Land League.[40]

When a man takes a farm from which another has been evicted, you must show him on the roadside when you meet him, you must show him in the streets of the town, you must show him at the shop-counter, you must show him in the fair and at the marketplace, and even in the house of worship ... you must show him your detestation of the crime he has committed ... if the population of a county in Ireland carry out this doctrine, that there will be no man ... [who would dare] to transgress your unwritten code of laws.

Charles Stewart Parnell at the Ennis meeting, 19 September 1880[41][42]

One of the League's main tactics was the boycott,[43][44] whose most common target was "land grabbers".[45] However, it did not invent the stratagem of ostracizing those who violated the rural code. Land League speakers (including Michael Davitt) advocated that the tactic be used instead of violence on those who seized land which had been worked by evicted tenants.[46] The word "boycott" was coined later that year, after the successful campaign against unpopular land agent Charles Boycott. Although Boycott was forced to leave the country,[47] the boycott's overall effectiveness was disputed and may have been overestimated by contemporary observers.[48] Consequences of the boycott were described by Lord Fitzwilliam, a pro-landlord advocate, in 1882: "When a man is under the ban of the League no man may speak to him, no one may work for him; he may neither buy nor sell; he is not allowed to go to his ordinary place of worship or to send his children to school."[44] The use of "intimidation" to enforce a boycott was criminalized that year in the Prevention of Crime Act.[49][50]

In his 1892 book, Ireland under the Land League, Charles Dalton Clifford Lloyd described how the law's enforcement was difficult because many people refused to cooperate with the official justice system. Refusal to rent transportation equipment to the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) paralyzed the police in Kilmallock, and people turned to the Land League rather than magistrates to resolve disputes. If a person observed the official law, they were denounced for breaking the unwritten code.[51] Lloyd complained that instead of petitioning the government for a change in the laws, "the Land League established laws of its own making, formed local committees for the government of districts, instituted into own local tribunals, passed its own judgements, executed its own sentences, and generally usurped the functions of the crown".[52] Lloyd and other observers believed that the League was not just a competing government, but the only effective one in many parts of Ireland;[52][53] a modern observer noted that "(t)here were areas of the country which simply could not be controlled by the British government."[54] In 1881, Chief Secretary for Ireland William Edward Forster said that Land League law was ascendant:

... All law rests on the power to punish its infraction. There being no such power in Ireland at the present time, I am forced to acknowledge that to a great extent, the ordinary law of the country is powerless; but the unwritten law is powerful, because punishment is sure to follow its infraction.[55]

Conservative jurist James Fitzjames Stephen wrote that boycotts amounted to "usurpation of the functions of government", and should be considered "the modern representatives of the old conception of high treason".[52][56] The government passed the Protection of Persons and Property Act 1881, which provided for the detention without trial of anyone suspected of treasonous activity or who tried to subvert the rule of law, to combat the underground state. Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone had previously refused to suspend habeas corpus, saying that a Coercion Act would only be justified if Land League agitation threatened not only individuals but the state itself.[57]

National League

The Irish National League (1882–1910) was a more-moderate association which replaced the Land League after the latter was suppressed.[58] The key provisions of the National League's code forbade paying rent without abatements, taking over land from which a tenant had been evicted, and purchasing their holding under the 1885 Ashbourne Act (except at a low price).[59] Other forbidden activities included "participating in evictions, fraternizing with, or entering into, commerce with anyone who did; or working for, hiring, letting land from, or socializing with, [a] boycotted person".[60] The League enforced its code with informal tribunals, typically led by the leaders of local chapters. The National League's courts held their proceedings openly, and followed a common-law procedure. This was intended to uphold the League's image favouring the rule of law (Irish, rather than English law).[61]

Contemporaries considered the National League a legitimate authority. One Home Rule supporter, the Liberal parliamentary candidate Montague Cookson, said that home rule had already arrived: "The decrees of the Government of the Queen are set at naught in the three counties I have mentioned [Cork, Limerick, Clare], while those of the League are instantly and implicitly obeyed."[62][63] Magistrates and law-enforcement officials agreed with this assessment in their testimony to the Cowper Commission in 1886.[62] According to historian Perry Curtis, the National League was "a self-constituted authority with powers parallel to those of the established government".[62]

United Irish League

The United Irish League (1898–1910) was an agrarian protest organization based in Connacht, with branches throughout the country, which sought redistribution of land from graziers to smallholders and (later) compulsory purchase of land by tenants at favourable prices.[28][64] After passage of the Land Purchase (Ireland) Act 1903, the League campaigned for the sale of estates (including untenanted land) to tenants at low prices and the reduction of rent to the level of the annuities paid by new freeholders.[65] The modus operandi of local UIL branches was to send young men to demand that graziers give up their land.[66][67] If a compromise could not be reached, the grazier would be summoned to a meeting for his case to be considered.[68] Refusal to attend resulted in the League's highest penalty: the boycott.[69] UIL activists considered that grazing farms violated "unwritten law" because much of the land had been taken from evicted tenants; the fact that many graziers did not live on their holdings made it easier to brand them "land grabbers".[70]

Local UIL branches acted as courts, claiming jurisdiction over all matters relating to land in their area. People accused of violating the League's code would be summoned to a meeting with the plaintiff and the board of the local UIL chapter; evidence would be heard, a verdict reached and punishment imposed.[71] The procedure was very similar to that used by British petty sessions.[72] The plaintiff typically acted as prosecutor, following a strict procedural code. Defendants were given sufficient notice to prepare a defence, and were allowed to appeal compensation demanded by plaintiffs. Decisions made by a parish court could be appealed to an executive court.[73] In 56 of 117 cases examined by Irish historian Fergus Campbell, the verdict was to censure the defendant; this typically led to a boycott.[74] The appearance of fairness and impartiality was essential to encourage parties to bring their grievances to UIL courts, and the branches strove to maintain that image. Decisions were published in local nationalist newspapers, allowing UIL leaders to be accountable for their rulings. Campbell found no case in which a UIL court wrongly convicted an innocent man.[75]

Although the "law of the League" was partially derived from the central leadership's guidance and its 1900 constitution, local branches also pressured national leaders to include their own issues. The UIL's priorities shifted from anti-grazier agitation to land purchase. According to the police, their courts' verdicts were enforced by "boycotting, intimidation, and thinly veiled allusions in the Press".[28] Police received reports of 684 boycotts and 1,128 cases of intimidation, about two-thirds of agrarian offences, between 1902 and 1908.[76] Demonstrating the UIL courts' close connection to the concept of "unwritten law", the harshest penalties were reserved for "land-grabbers". After passage of the 1898 Local Government Act, which delegated some governmental powers to local elected councils, the UIL competed in local elections. It flew its flag over the court building if it was victorious, although such victories helped legitimize the British justice system.[77]

The courts were central to UIL agitation, because they dictated the targets and manner of agitation.[28] Between October 1899 and October 1900, over 120 cases were heard.[69] The inspector general said in 1907, "The law of the land has been openly set aside and the unwritten law of the League is growing supreme."[78] British historian Philip Bull described the UIL as a "proto-state".[79]

Dáil Courts

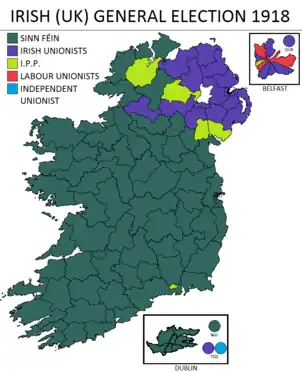

The new Sinn Féin party put arbitration courts into its program after its 1917 Ardfheis,[80] and established them throughout the country. According to party leader Arthur Griffith, "It was the duty of every Irishman" to obey the arbitration courts rather than seek justice from British courts.[81] The courts were favoured by Sinn Féin because they adhered to the principle of self-reliance in all matters, and arbitration between two parties in a dispute was legal and binding when the participants agreed to abide by a verdict.[81] Unlike the agrarian-society courts, Sinn Féin's courts claimed jurisdiction over crime and enforced a written constitution.[28][82]

Adhering to the party's policy of abstentionism, Sinn Féin MPs who were elected in the 1918 general election refused to take their seats in Westminster and set up the Dáil Éireann, a rival parliament.[83][84] In August 1919, during the Irish War of Independence, the Dáil announced the formation of a national court system for its nascent Irish Republic. The system included local parish courts, district courts, and a court of appeal. Parish courts dealt with petty crime and civil cases under £10, providing inexpensive and convenient access to justice. Local judges were elected and all officials received a salary, which cost the state an estimated £113,000.[84][85] The initial pretense of voluntary arbitration was dropped, and verdicts were enforced by the Irish Republican Army (IRA).[86] The resulting system had a high level of local initiative, with the Dáil exercising very little power.[87] Because the maintenance of British rule had come to rely so heavily on the police and courts to enforce its power, the rest of the Republic's apparatus would have been a "pitiful charade" if the Dáil Courts had not become popular.[87]

Their operation was very similar to the British courts they replaced, and historian Mary Kotsonouris described them as "primarily concerned with the protection of property".[83] The courts had a reputation for fairness, and even unionists respected their role in maintaining order.[88][89] Known for their "conservative, almost reactionary character",[87] they are "widely considered to be one of the greatest successes of the First Dáil".[89] According to Irish unionist peer Lord Dunraven,

An illegal government has become the de facto government. Its jurisdiction is recognised. It administers justice promptly and equably and we are in this curious dilemma that the civil administration of the country is carried on under a system, the existence of which the de jure government does not and cannot acknowledge and is carried on very well.[90][91]

The Dáil Courts also brought all subversive agrarian courts[92] and IRA courts-martial, which had been operating in some areas after the withdrawal of the Royal Irish Constabulary,[93] under the jurisdiction of the Dáil. The Dáil Courts refused to hear cases dealing with land issues, and in some cases the IRA was called in to remove squatters from private property.[89][92] By 1921, those who used British courts were accused of "assisting the enemy in time of war".[90] The IRA attacked everyone connected with the British judicial system, and declared that "every person in the pay of England (magistrates and jurors, etc.) will be deemed to have forfeited his life".[94] Intimidation led many JPs to resign, and some RMs were assassinated.[95] The RIC lost control of much of Ireland due to the Irish War of Independence, and rulings from British courts could not be enforced. Suppressed by the British government, the courts continued to operate underground.[88] Their activity peaked during the July–December 1921 truce, when they were busy dealing with ratepayers who failed to pay taxes to the Republic.[96]

As a result of the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty, the British courts were turned over to the Irish Free State.[85] Count Plunkett requested a petition of habeas corpus for the detention without trial of his son, George (an anti-Treaty guerilla), in 1922 after the split between Irish nationalists over the treaty.[89] The judge, Diarmuid Crowley, ordered the younger Plunkett's release; however, Crowley was arrested by the Free State government.[97] The Dáil court system was shut down and declared illegal after this incident, although a commission was appointed to iron out the loose ends in open cases. The courts were officially abolished by the Dáil Éireann Courts (Winding Up) Act 1923.[89][85]

References

- Citations

- 1 2 Laird 2005, p. 11.

- ↑ Ledwidge 2017, p. 21.

- ↑ Monaghan 2002, p. 42.

- 1 2 Mac Giolla Chríost 2004, p. 87.

- ↑ Linebaugh 2008, p. 136.

- ↑ Bull 1996, pp. 51–52.

- ↑ Vaughan 1994, p. 221.

- ↑ Laird 2005, pp. 11, 13.

- ↑ Laird 2005, p. 127.

- ↑ Bull 1988, p. 27.

- ↑ Laird 2005, pp. 13, 26.

- ↑ Jordan 1998, pp. 148–149.

- ↑ Laird 2005, p. 65.

- ↑ Jordan 1998, pp. 149–150.

- ↑ Jordan 1998, pp. 150–151.

- ↑ Jordan 1998, p. 151.

- ↑ Jordan 1998, pp. 151–152.

- ↑ Jordan 1998, p. 148.

- 1 2 Kenny 1998, p. 13.

- ↑ Jordan 1994, pp. 77, 89, 94.

- ↑ Vaughan 1994, pp. 190–191.

- ↑ Mac Suibhne 2017, p. 24.

- ↑ Monaghan 2002, p. 41.

- ↑ Kenny 1998, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Jordan 1994, pp. 89–90.

- ↑ Kenny 1998, p. 19.

- ↑ Jordan 1994, p. 89.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Campbell 2005, p. 3.

- 1 2 Jordan 1998, p. 162.

- ↑ Kenny 1998, p. 20.

- ↑ McCaffrey 2015, p. 90–91.

- ↑ Casey 1974, p. 326.

- ↑ Mac Suibhne 2017, pp. 174–175.

- ↑ Monaghan 2002, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Bull 1996, pp. 95–96.

- 1 2 Ledwidge 2017, p. 40.

- ↑ Jordan 1998, pp. 161–162.

- ↑ Laird 2005, p. 27.

- ↑ Campbell 2005, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Townshend 1984, p. 130.

- ↑ Jordan 1994, p. 286.

- ↑ Laird 2005, pp. 29–30.

- ↑ Townshend 1984, pp. 116, 130.

- 1 2 Laird 2005, p. 28.

- ↑ Laird 2013, p. 185.

- ↑ Jordan 1994, pp. 285–286.

- ↑ Jordan 1994, pp. 286, 289.

- ↑ Townshend 1984, p. 116.

- ↑ Laird 2005, p. 34.

- ↑ Townshend 1984, p. 173.

- ↑ Laird 2005, pp. 26–27.

- 1 2 3 Laird 2005, p. 36.

- ↑ Townshend 1984, p. 125.

- ↑ Fraser, Rebecca (2005). The Story of Britain: From the Romans to the Present: a Narrative History. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06010-2.

- ↑ Laird 2005, p. 35.

- ↑ Laird 2013, pp. 185–186.

- ↑ Laird 2005, p. 37.

- ↑ Jackson 2003, p. 46.

- ↑ Jordan 1998, p. 152.

- ↑ Jordan 1998, p. 159.

- ↑ Jordan 1998, pp. 159, 161.

- 1 2 3 Jordan 1998, p. 147.

- ↑ Laird 2005, p. 39.

- ↑ Laird 2005, pp. 121–122.

- ↑ Campbell 2005, p. 7.

- ↑ Bew 1987, p. 43.

- ↑ Campbell 2005, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Campbell 2005, p. 2.

- 1 2 Laird 2005, p. 122.

- ↑ Laird 2005, pp. 115–116.

- ↑ Campbell 2005, pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Campbell 2005, p. 12.

- ↑ Campbell 2005, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Campbell 2005, p. 13.

- ↑ Campbell 2005, pp. 9–10.

- ↑ Campbell 2005, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Laird 2005, pp. 122–123.

- ↑ Campbell 2005, p. 1.

- ↑ Bull 2003, p. 422.

- ↑ Casey 1974, p. 327.

- 1 2 Ledwidge 2017, p. 44.

- ↑ Ledwidge 2017, p. 53.

- 1 2 Laird 2005, p. 123.

- 1 2 Ledwidge 2017, p. 51.

- 1 2 3 Monaghan 2002, p. 43.

- ↑ Hughes 2017, pp. 83–84.

- 1 2 3 O'Brien 1996, p. 296.

- 1 2 Ledwidge 2017, p. 52.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Coleman 2006, p. 260.

- 1 2 Laird 2005, p. 124.

- ↑ Ledwidge 2017, p. 55.

- 1 2 Laird 2005, pp. 126–127.

- ↑ Hughes 2017, p. 84.

- ↑ Ledwidge 2017, p. 54.

- ↑ Hughes 2017, p. 44.

- ↑ Hughes 2017, p. 69.

- ↑ Kotsonouris 1994, pp. 87–88.

- Sources

- Bew, Paul (1987). Conflict and Conciliation in Ireland, 1890–1910: Parnellites and Radical Agrarians. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198227588.

- Bull, Philip (1988). "Land and Politics, 1879–1903". In Boyce, David George (ed.). The Revolution in Ireland, 1879-1923. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan. pp. 24–46. ISBN 9780717115563.

- Bull, Philip (1996). Land, Politics and Nationalism: a Study of the Irish Land Question. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan. ISBN 9780717121908.

- Bull, Philip (2003). "The Formation of the United Irish League, 1898–1900: the Dynamics of Irish Agrarian Agitation". Irish Historical Studies. 33 (132): 404–423. doi:10.1017/S0021121400015911. ISSN 0021-1214. S2CID 163473592.

- Campbell, Fergus (2005). "The 'Law of the League': United Irish League Justice, 1898–1910". Land and Revolution: Nationalist Politics in the West of Ireland 1891–1921. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199273249. From an Oxford Handbooks reprint paginated 1–45, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199273249.001.0001

- Casey, J. P. (1974). "The Genesis of the Dáil Courts". Irish Jurist. 9 (2): 326–338. ISSN 0021-1273. JSTOR 44026195.

- Coleman, Marie (2006). "The winding up of the Dáil courts, 1922–1925: an obvious duty. By Mary Kotsonouris. Pp xi, 269, illus. Dublin: Four Courts Press, for the Irish Legal History Society. 2004. €55". Irish Historical Studies. 35 (138): 260–261. doi:10.1017/S0021121400005058. ISSN 0021-1214. S2CID 159741833.

- Hughes, Brian (2017). Defying the IRA? Intimidation, Coercion, and Communities During the Irish Revolution. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 9781781383544.

- Jackson, Alvin (2003). Home Rule: An Irish History, 1800–2000. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195220483.

- Jordan, Donald (1994). Land and Popular Politics in Ireland: County Mayo from the Plantation to the Land War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521466837.

- Jordan, Donald (1998). "The Irish National League and the 'Unwritten Law': Rural Protest and Nation-Building in Ireland 1882–1890". Past & Present. Oxford University Press. 158 (158): 146–171. doi:10.1093/past/158.1.146. ISSN 0031-2746. JSTOR 651224.

- Kenny, Kevin (1998). Making Sense of the Molly Maguires. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198026624.

- Kotsonouris, Mary (1994). Retreat from Revolution: the Dáil Courts, 1920-24. Irish Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-7165-2511-0.

- Laird, Heather (2005). Subversive Law in Ireland, 1879-1920: from Unwritten Law to Dáil Courts (PDF). Dublin: Four Courts Press. ISBN 9781851828760.

- Laird, Heather (2013). "Decentring the Irish Land War: women, politics and the private sphere". In Campbell, Fergus; Varley, Tony (eds.). Land Questions in Modern Ireland. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 175–193. ISBN 978-0-7190-7880-4.

- Ledwidge, Frank (2017). Rebel Law: Insurgents, Courts and Justice in Modern Conflict. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9781849049238.

- Linebaugh, Peter (2008). "Review of Subversive Law in Ireland, 1879–1920: from 'Unwritten Law' to the Dáil Courts". Irish Economic and Social History. 35: 135–142. doi:10.7227/IESH.35.8. ISSN 0332-4893. JSTOR 24338511.

- Mac Giolla Chríost, Diarmait (2004). The Irish Language in Ireland: From Goídel to Globalisation. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203504826. ISBN 9781134361243.

- Mac Suibhne, Breandán (2017). The End of Outrage: Post-Famine Adjustment in Rural Ireland. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191058646.

- McCaffrey, Lawrence J. (2015). Daniel O'Connell and the Repeal Year. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813163543.

- Monaghan, Rachel (2002). "The Return of "Captain Moonlight": Informal Justice in Northern Ireland" (PDF). Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. 25 (1): 41–56. doi:10.1080/105761002753404140. ISSN 1057-610X. S2CID 108957572.

- O'Brien, Gerard (1996). "Retreat from revolution: the Dáil courts, 1920–24. By Mary Kotsonouris. Pp 172. Dublin: Irish Academic Press. 1994. IR£22.50". Irish Historical Studies. 30 (118): 296–297. doi:10.1017/S0021121400013080. ISSN 0021-1214. S2CID 204472776.

- Townshend, Charles (1984). "Land War". Political Violence in Ireland. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 105–180. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198200840.001.0001. ISBN 9780198200840.

- Vaughan, William Edward (1994). Landlords and Tenants in Mid-Victorian Ireland. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198203568.