| Upper Iowa River Oneota site complex | |

|---|---|

View of O'Regan Site | |

| Location | on the Iowa River in Allamakee County, Iowa |

| Coordinates | 43°25′00″N 91°21′00″W / 43.41667°N 91.35000°W |

Location in Iowa  Location in United States | |

The Upper Iowa River Oneota site complex is a series of 7 Iowa archaeological sites located within a few miles of each other in Allamakee County, Iowa, on or near the Upper Iowa River. They are all affiliated with the Late Prehistoric Upper Mississippian Oneota Orr focus. In some cases there are early European trade goods present, indicating occupation continued into the Protohistoric or early Historic period.[1]

All 7 sites were excavated in 1934 and 1936 by Dr. Charles Reuben Keyes and Mr. Elliason Orr:[1]

- Lane Village site and mound group (13Ae18 and 13Ae19)

- Elephant Cemetery site (13Ae13)

- O'Regan Cemetery site (13Ae12)

- New Galena mound group (13Ae5)

- Hogback site / Flatiron terrace (13Ae3)

- Burke site (13Ae6)

- Woolstrom site / Flynn Cemetery (13Ae38)

The full site report was produced in 1959 by Mildred Mott Wedel. Due to the cultural similarities and close proximities of the sites, the data were combined for analytical purposes.[1]

Environment

The Upper Iowa valley contained several ecosystems which provided resources to the prehistoric inhabitants. The river itself provided abundant fish, mussels and turtles. The floodplain contained rich soil for agriculture. The terraces overlooking the river were well-forested with oak, maple, hemlock, elm, as well as nut trees such as hickory, black walnut and butternut, to supplement the agricultural diet. The forests also provided habitat for deer. Beyond the terraces were the prairies which provided habitat for elk and bison.[1]

Results of data analysis

Excavations at the site yielded Prehistoric and Historic artifacts, pit features, burials, animal bone and plant remains. The Lane site, being the only village site in the group, yielded the greatest variety of artifacts.[1]

Structures and features

At the Lane site, a circular enclosure or "pottery circle" was noted by early settlers. Cyrus Thomas of the Bureau of American Ethnology surveyed the area in 1882 and called this enclosure a "palisade". Since that time it's been proposed to have been a fortification or to have served a dance / ceremonial function.[2][1]

No residential structures were found at any of the sites. It is thought that the dwellings of the Prehistoric inhabitants were simple structures with a log frame draped over with mats and/or skins. Such dwellings were not substantial enough to leave behind any house patterns or post molds.[1]

Over 50 bowl- or wedge-shaped storage/refuse pits were encountered during excavations. It was felt that the storage/refuse pits started out as storage pits to keep foods fresh longer; as the food in them soured, they then were used as refuse pits while fresh storage pits were dug elsewhere. They contained culturally rich fill with potsherds, stone tool debris, animal bone, plant remains, etc.[1]

Several features were classified as "roasting pits" or "fire pits" due to the presence of charcoal and ash. These features were probably used to cook food for consumption. Two were reported at the Lane site and their presence was recorded at O'Regan.[1]

Burials

Burials were present at all 7 sites. The total number of burials was 66, of which more than half (34) came from the O'Regan site. All burials were primary and extended, and numerous grave goods were recovered, including pottery, shell spoons, smoking pipes and stone tools.[1]

Plant and animal remains

There was no effort to systematically collect and analyze animal and plant remains at any of the sites, because the archaeology of that age was still focused primarily on the artifacts. Early observers mentioned "immense amounts" of animal bone present at the Lane site, specifically bison, fish, mussel shell, bird, rabbit, fox, bear, wolf, elk and antelope. With respect to plants, corn, beans and birch bark were mentioned, and a pit at the Lane site was noted to be lined with grass.[1]

Artifacts

Pottery artifacts

Archaeologists often find pottery to be a very useful tool in analyzing a Prehistoric culture. It is usually very plentiful at a site and the details of manufacture and decoration are very sensitive indicators of time, space and culture.[3]

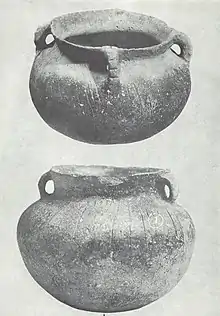

Pottery was found at all 7 sites. The analysis was based on 17 complete vessels and 2,072 sherds.[1]

Pottery type Allamakee trailed

The pottery is similar enough that the vast majority can be placed in a single type created by Mildred Wedel called Allamakee trailed. Vessel form is globular to elliptical, round bottomed jars with restricted orifice and flared rim profile. The vessels are shell-tempered and the surface finish is smoothed. Decoration is applied between the neck and shoulder and consists of rectilinear patterns combined with punctates. The lip is thinned and straightened and usually notched or scalloped. Strap handles or loop handles are often present.[1]

Other artifacts

Non-pottery artifacts recovered from the site included:[1]

- Chipped stone artifacts - including 102 projectile points, 20 knives (subdivided into variants based on shape), 79 scrapers (subdivided into variants based on shape and wear patterns), 18 scraper-knives, 17 expanded-base drills, 3 gravers, 2 bi-pointed objects, 2 core choppers and one celt. Of the projectile points, the most numerous category (97) was the small triangular Madison point.

- Ground stone artifacts - including 5 mullers, 1 hammerstone, 1 grooved hammer, 2 chisels, 1 ball and 8 rubbing stones.

- Stone pipes - including 3 elbow pipes, 2 projecting-stem "Siouan" pipes, 1 effigy head elbow pipe with projecting stem and disk bowl and 1 flat base monitor pipe

- Bone and antler artifacts - including 13 scapula hoes, 2 bone scrapers, 1 bone wrench, 4 needles, 6 hair tubes, 4 beads, 17 perforators/awls of various type, 4 antler projectile points, 2 antler flakers and 1 game counter

- Shell artifacts - including 3 spoons, an awl, a bead and a pendant

- Copper - including 11 rolled hair tubes, 1 ring, 1 bracelet, 2 serpent figurines, and 5 coils

- European trade goods - including glass beads, 1 iron nail, 2 iron knife fragments and 3 misc. iron fragments

The non-pottery artifacts found at an archaeological site can provide useful cultural context as well as a glimpse into the domestic tasks performed at a site; ceremonial or religious activities; recreational activities; and clothing or personal adornment.[4]

Some of the most prominent and diagnostic non-pottery artifacts are presented here in more detail:[1]

| Material | Description | Image | Qty | Function / use | Comments / associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chipped stone | Small triangular points (aka Madison points) | 97 | Hunting/fishing/warfare | These specimens are from the Lane Village Site. Also known as "arrowheads"; are thought to be arrow-tips for bows-and-arrows. The usage of the bow-and-arrow seems to have greatly increased during the Late Woodland, probably as a result of increased conflict.[5][6] | |

| Chipped stone | Biface blades/knives |  |

20 | Domestic function / cutting applications | Typical of Upper Mississippian sites, particularly Huber and Oneota (Orr focus)[7] |

| Chipped stone | Snub-nosed end scrapers |  |

15 | Domestic function / processing wood or hides | Typical of Upper Mississippian sites, particularly Huber and Oneota (Orr focus); most came from the Lane Enclosure; this type has been described as "humpback end scraper" at the Griesmer site[7] |

| Ground Stone | Smoking Pipe - elbow-projecting stem type |  |

1 | Ceremonial-Recreational function / pipe smoking | From the Burke Cemetery site; stemmed pipes were used for ceremonial purposes; stemless pipes were used for everyday smoking[4] |

| Ground Stone | Arrow shaft straightener |  |

1 | Domestic function / straightening arrow shafts for bows-and-arrows | Typical at Upper Mississippian sites;[7] this specimen is from the O'Regan Cemetery site |

| Bone | Scapula hoes (bison or elk) |  |

13 | Domestic function / Agricultural-horticultural or general digging tool | Common at Fisher and Oneota sites;[7] most came from the Lane site; they may have been used to dig out the burials and pit features present at the Orr Phase site complex. |

| Bone | Bone tubes |  |

6 | Personal Adornment and/or Ceremonial function / necklace | From the Lane site; Common at Upper Mississippian sites;[7] may have been used for personal adornment and/or as part of a costume for a ceremony |

| Bone | Bone cylinders / game pieces |  |

1 | Entertainment function | This specimen comes from the Lane site. These have been found at Fisher, Huber, Langford and Oneota (especially Grand River focus and Lake Winnebago focus) and may have been used in a gambling game.[7] Gambling was noted to be a popular pastime among the early Native American tribes.[8][9] |

| Copper | Copper serpents |  |

2 | Art piece or Religious function | Similar copper serpent figurines have been found at other sites in the American Midwest region: the Anker Site near Chicago, Illinois; the Summer Island site in Michigan;[10] and the Madisonville site in Ohio.[11] The Orr focus sites, Madisonville and Summer Island all have early European trade goods associated, indicating these figurines were still being made at the time of European contact. |

Orr focus

The Orr focus is a regional manifestation of the Upper Mississippian Oneota cultures which were present throughout the American Midwest in the late Prehistoric and Protohistoric to early Historic periods. The subsistence base of the Orr focus people, like most Upper Mississippians, was primarily agricultural supplemented by hunting, fishing and gathering.[12]

The 7 sites in the Upper Iowa complex are the type sites for the Orr focus. Other Orr focus sites in Wisconsin include Shrake-Gillies, Midway and Pammel Creek. The Orr focus is distinctive from other Oneota Foci mainly in terms of the pottery which is based on rectilinear (instead of curvilinear) decoration and frequent notching on the lip.[1]

External relationships

It has been pointed out that the Huber Phase pottery (from the Chicago area) very closely resembles Orr focus. Specifically, Huber Trailed is thought to be a very similar type to Allamakee Trailed. Huber Trailed has rectilinear patterns, lip notching and very similar vessel form to Allamakee Trailed. A detailed comparison of pottery from a Huber site (Oak Forest) and an Orr focus site (Midway) did reveal some differences between them: the lips on Orr pottery were almost always rounded, which Huber lips could be rounded, flattened or beveled; the rim profiles on the Orr pottery were almost always vertical while the Huber pottery more often had inward or outward curve; the Huber necks were more often angular while the Orr necks were more often curved; and trailed lines were more often to be combined with punctate decoration on Orr than Huber.[13]

Both Orr focus and Huber have been dated to the late Prehistoric to Protohistoric to early Historic periods. Radiocarbon dates on 6 samples from the Lane site ranged from A.D. 1426-1660 and Huber sites such as Oak Forest show a similar date range, with associated European trade goods.[14]

An Allamakee Trailed vessel has been reported from early Historic contexts at the Rock Island II Site in Door County, Wisconsin, situated in Green Bay (Lake Michigan). The stratum was dated to a mixed Huron-Petun-Ottawa (proto-Wyandot) occupation dated to A.D. 1650/51 to 1653. This narrow date range was possible because Ronald Mason found specific references to this occupation in the early French records. The presence of this vessel at Rock Island is significant because it demonstrates the Orr focus was still in existence in the early Historic period.[15]

The seven sites on the Upper Iowa River are located in the same area that the early French explorers and fur traders found the Ioway Native American tribe. Archaeologists are in general agreement that the Orr Phase pottery represents the Prehistoric cultural remains of the Ioway tribe, as well as the closely related Otoe tribe.[1]

Significance

The efforts of Keyes and Orr in excavating 7 sites on the Upper Iowa River resulted in the recognition of a new division within the Upper Mississippian culture group, the Oneota Orr focus. The main diagnostic artifact of this focus is the shell-tempered Allamakee Trailed pottery. The Orr focus has been radiocarbon dated to the late Prehistoric to Protohistoric and early Historic Periods, and the artifacts recovered confirm this late date. it is believed to represent the Prehistoric culture of the Ioway and Otoe tribes.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Wedel, Mildred Mott (1959). "Oneota Sites on the Upper Iowa River". The Missouri Archaeologist. 21 (2–4): 1–181.

- ↑ Thomas, Cyrus (1887). "Burial Mounds of the Northern Section of the United States". Bureau of American Ethnology, Fifth Annual Report: 38–109.

- ↑ Shepard, Anna O. (1954). Ceramics for the Archaeologist. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington, Publication 609.

- 1 2 Bettarel, Robert Louis; Smith, Hale G. (1973). The Moccasin Bluff Site and the Woodland Cultures of Southwest Michigan. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology, Anthropological Papers No. 49.

- ↑ Mason, Ronald J. (1981). Great Lakes Archaeology. New York, New York: Academic Press, Incl.

- ↑ Lepper, Bradley T. (2005). Ohio Archaeology (4th ed.). Wilmington, Ohio: Orange Frazer Press.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Faulkner, Charles H. (1972). "The Late Prehistoric Occupation of Northwestern Indiana: A Study of the Upper Mississippi Cultures of the Kankakee Valley". Prehistory Research Series. V (1): 1–222.

- ↑ Kinietz, W. Vernon (1940). The Indians of the Western Great Lakes 1615-1760 (1991 ed.). Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

- ↑ Blair, Emma Helen (1911). The Indian Tribes of the Upper Mississippi Valley and Region of the Great Lakes (1996 ed.). Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.

- ↑ Brose, David S. (1970). The Archaeology of Summer Island: Changing Settlement Patterns in Northern Lake Michigan. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology, Anthropological Papers No. 41.

- ↑ Hooton, Earnest A. and Charles C. Willoughby (1920). "Indian Village Site and Cemetery near Madisonville, Ohio". Papers of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology. 8 (1).

- ↑ Brown, James A. (1990). "Part II: The Oak Forest Site: Investigations into Oneota Subsistence-Settlement in the Cal-Sag Area of Cook County, Illinois". In Brown, James A.; O'Brien, Patricia J. (eds.). At the Edge of Prehistory: Huber Phase Archaeology in the Chicago Area. Kampsville, Illinois: Center for American Archaeology.

- ↑ Michalik, Laura K.; Brown, James A. (1990). "Chapter 10: Ceramic Artifacts". In Brown, James A.; O'Brien, Patricia J. (eds.). The Oak Forest Site: Investigations into Oneota Subsistence Settlement in the Cal-Sag Area of Cook County, Illinois, IN At the Edge of Prehistory: Huber Phase Archaeology in the Chicago Area. Kampsville, Illinois: Center for American Archaeology.

- ↑ Brown, James A.; Asch, David L. (1990). "Chapter 4: Cultural Setting: the Oneota Tradition". In Brown, James A.; O'Brien, Patricia J. (eds.). The Oak Forest Site: Investigations into Oneota Subsistence-Settlement in the Cal-Sag Area of Cook County, Illinois, IN At the Edge of Prehistory: Huber Phase Archaeology in the Chicago Area. Kampsville, Illinois: Center for American Archaeology.

- ↑ Mason, Ronald J. (1986). Rock Island: Historical Indian Archaeology in the Northern Lake Michigan Basin. Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press, MCJA Special Paper No. 6.

Further reading

- Mildred Mott Wedel (1959), "Oneota Sites on the Upper Iowa River", The Missouri Archaeologist, 21 (2–4): 1–181