The Ursari (generally read as "bear leaders" or "bear handlers"; from the Romanian: urs, meaning "bear"; singular: ursar; Bulgarian: урсари, ursari) or Richinara are the traditionally nomadic occupational group of animal trainers among the Romani people.

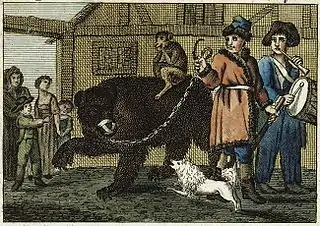

An endogamous category originally drawing the bulk of its income from busking performances in which they used dancing bears, usually brown bears and, in several instances, Old world monkeys. They have largely become settled after the 1850s. The Ursari form an important part of the Roma community in Romania, where they are one of the 40 tribal groups,[1] as well as notable segments of the Bulgarian Roma population and of the one in Moldova. They also form a sizable part of the Roma present in Serbia and in Western European countries such as the Netherlands and Italy.

The word Ursari may also refer to a dialect of Balkan Romani, as spoken in Romania and Moldova,[2][3] although it is estimated that most Ursari, like the Boyash, speak Romanian as their native language.[4] There is no scholarly consensus on whether Ursari belong to the Sinti subgroup of the Roma people or to the other half of the Roma population.[5] A Romanian poll conducted in 2004 among 347 Roma found that 150 referred to themselves as "Ursari" (or 43.2%, and the largest single group).[6]

The Romanian-speaking Roma bear or monkey handlers in Bulgaria, called mechkari (мечкари), maymunari, or ursari, are occasionally seen as a separate community[3] or as a distinct part of the Boyash population,[7] as are persons identified as Ursari in Italy.[8] The Coşniţari (or koshnichari) group, present on both sides of the Danube (in both Romania and Bulgaria), is believed to be a segment of the Ursari.[9] Other such Eastern European groups, although linked by profession, speak different languages and dialects, and are considered to be not a part of the Ursari; they include the Medvedara in Greece, Ričkara in Slovakia, The Muslim Arixhinj in Albania and the Muslim Ayjides in the Istanbul area of Turkey.[10]

History

Early migrations and slavery

Groups of bear-handlers are known to have existed during the population's transit through the Byzantine Empire, as early as the 12th century, when they are mentioned in connection with the Athinganoi (Roma people) by Theodore Balsamon.[4] In later decades, they were probably among the people collectively referred to as "Egyptians".[4]

The Ursari formed part of the slave population in the Danubian Principalities (Moldavia and Wallachia) before the abolitions of the 1840s and 1850s. With the Boyash (including the gold-prospecting Zlătari), the Kalderash, and groups of Roma smiths, Ursari formed the category of lăieşi, who, unlike vătraşi slaves, were allowed to carry on with a nomadic lifestyle (being required by their boyar masters to pay various benefits in exchange for the permission).[11][12]

By the early decades of the 19th century, most of the state-owned Roma were lăieşi, as opposed to private-owned ones.[9][11][13] The lăieşi were required to contribute an annual sum to the treasuries of Wallachia and Moldavia;[12][13] Édouard Antoine Thouvenel, a French diplomat who visited Wallachia during the period, indicated that, for Ursari families, this sum amounted to between twenty and thirty piasters,[13] and it is documented that the Boyash and the Ursari paid equivalent fees.[12]

Like other nomadic Roma, Ursari are known to have travelled in large tribal groups during the 20th century,[14] although other sources indicate that they preferred to organize themselves on a tight and selective family-based structure.[15] Ursari people and the Boyash-proper traditionally accompanied the Kalderash on their travels to Rumelia, contributing to the birth of the Mechkara community.[7]

Thouvenel described the group's "miserable condition", and, in reference to their handling of brown bears, wrote: "[...] they reunite to give chase to [the bears], whom they domesticate after capturing them in their youth, or whom they render unable to harm them. Bears in the Carpathians are, after all, much smaller and of a less ferocious nature than those in the Nord; their leaders train them with relative ease and run around from village to village in order to collect a few para as a result of peasant curiosity".[13]

Also according to Thouvenel, Ursari were known for "veterinary skills", which, he argued, "the superstition of people in the countryside attributes to the possession of a magic art".[13] In addition to bear handling, the community would occasionally trade in wild animals (specifically bear cubs),[9] and was known for keeping and training monkeys.[7][16] Female members of the community were known for their practice of fortune-telling.[14][15]

Emancipation

Speaking during the late 1880s, the historian and politician Mihail Kogălniceanu, who was responsible for the 1855 abolition of slavery in Moldavia under Prince Grigore Alexandru Ghica, claimed that: "aside from the [other] lăieşi Gypsies, who still live in part in Gypsy camps, and Ursari, who are presently working in the taming of wild beasts, but are nevertheless involved in working the land, almost all of the other classes of Gypsies have blended into the larger mass of the nation, and are only told apart by their swarthy and Asian-like faces and the vividness of their imagination".[17]

Following the creation of a Romanian Principality, Ursari nonetheless remained a presence associated with busking and fairs, especially with those held in Bucharest and provincial cities such as Bacău.[14][18] As early as the rule of Domnitor Alexandru Ioan Cuza, they formed a staple of such spectacles, alongside the music-playing Lăutari, the Călușari, and freak shows.[18] At around the same time, they included a section of zavragii, smiths who worked as day laborers.[9] Also during the late 19th century, the Ursari came to be attested in Imperial Russian-ruled Bessarabia, where the local population referred to them and to the lăieși in general as șătrași ("people living on campsites").[9]

Sometime after 1850, groups of Ursari, Kalderash and Lovari, most likely coming from Austro-Hungarian regions and Bosnia, moved westwards, and were mentioned for the first time as present in the North Brabant and other areas in the Netherlands (where their descendants still live).[19][20] A similar move originated in Serbia, around Kragujevac, with Boyash and Ursari moving into northern and central Italy.[8] In the Netherlands, central authorities reacted vehemently to the presence of Roma, labeling Ursari and the others with the loaded term "Gypsies"; the reaction of local authorities was more calm, and allowed Ursari to blend into Dutch society, even though most members of the latter community intended to settle in other areas.[21]

Before and after the Porajmos

In time, a significant number of Ursari joined circuses,[8][22] while many others began manufacturing and trading bone objects and leather (as, respectively, Pieptănari and Ciurari), or associating with the Lăutari.[9][23] The bears were taught to make dancing moves to a tambourine,[22][18][23] or trained to walk upright and perform tricks such as leaning on canes and rolling over.[22][14] The use of iron rods and nose rings in the taming process, as well as other such practices, rose attention from animal welfare advocates, and have been the subject of criticism from as early as the 1920s, when Germany forbade the Ursari's trade.[22] It has been reported that bear training involved burning the paws of cubs to the rhythm of music.[24]

During the early stages of World War II, as part of the repressive measures ordered by the Iron Guard, the Minister of the Interior of the Romanian Legionary Government, Constantin Petrovicescu, passed an order preventing Ursari from performing with bears in cities, towns, or villages.[25] The official explanation for the measure was that such patterns of movement were helping to spread typhus.[25] Over the following years, under Ion Antonescu's regime, members of the Ursari community were among the Roma people deported to Transnistria, as part of Romania's share in the Holocaust (see also Romania during World War II and Porajmos).[1][25][26]

After World War II, interdictions on performing with bears were legislated throughout the Eastern Bloc.[22] In Communist Romania, large groups of Ursari performers were prevented from entering cities,[14] and, under both Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej and Nicolae Ceaușescu, nomadic Roma were subject to settlement policies[1][27][28] (many were reportedly resettled as early as their return from Transnistria).[28]

Post-Communism

In April–June 1991, following the Revolution of 1989, Ursari in several localities of Romania's Giurgiu County — Bolintin Deal, Ogrezeni and Bolintin Vale — were the target of ethnic violence. Ursari people were chased away, and many of their lodgings were burned to the ground.[27][29] In Bolintin Deal, where the first such actions took place, this came in retaliation for the murder of a Romanian student, Cristian Melinte, by a young Ursar hitchhiker who was later sentenced to 20 years in prison.[1][27][30][31]

The arsons were carried out by large groups of local inhabitants, who, according to American author Isabel Fonseca, acted methodically (they are alleged to have cut down the electrical wires leading to each Ursari house, so that the fire would be contained).[32] In Ogrezeni, inter-communal violence was caused by the stabbing of a Romanian during a bar fight.[1][27] In contrast, the violent acts in Bolintin Vale were unprovoked, and probably came as an effect of the Ogrezeni incident.[27]

Commentators have attributed these outbursts to the failure of settlement measures,[27][33] with the perception that former nomads were among the privileged class during Communist times.[33] It was reported that many Romanians in Bolintin Deal believed the Ursari were stealing property and even, in Fonseca's account, that they had been organizing photo ops for Ceauşescu.[34]

At the same time, criminal acts among the Ursari have been independently reported: among the Roma present in Bolintin Deal, the largely unemployed Ursari were not fully integrated; it was indicated that houses of non-Ursari Roma were not targeted during the 1991 events, and that, of the 27 criminal files instrumented in Bolintin between 1989 and 1991, 18 implicated Ursari people (with similar ratios in Ogrezeni).[27] It was also noted that the Bolintin Deal and Bolintin Vale mobs comprised not only Romanians, but also Roma belonging to traditionally settled communities.[27]

Romanian Police was criticized for its failure to intervene and prevent violence, despite being made aware of the potential for conflict[27] — in Bolintin Deal, 22 out of 26 Ursari houses were burned before the Jandarmeria and fire service dispersed the mob.[1][27] However, in Ogrezeni and Bolintin Vale, Police forces were themselves faced with violence from the mob, after allegations that they had vested interest in supporting the Roma community at large;[27] in Ogrezeni, 13 or 14 out of 15 Ursari houses were set on fire, and 11 were devastated in Bolintin Vale.[1][27]

All members of the Ursari community in Bolintin Deal settled in either Bucharest or Giurgiu, many of them after selling their plots of land; a group attempted to return in May 1991, but was chased away by the locals.[1][27] Reportedly, authorities informed the Ursari that they had better to run away.[1] By 2005, several Ursari who had taken residence in Bucharest Sector 4 requested to be issued deeds for formerly state-owned land in Bolintin Deal, which was then being allocated to residents; the local authorities denied their request, arguing that ownership of the land in question was still subject to dispute, and indicating that the Ursari could purchase other plots if they chose to do so.[30]

Ursari were a seasonal presence on the Black Sea Coast under the Bulgarian Communist regime.[24] Though much rarer, bear leading is still practiced by nomadic groups of Ursari in various areas of Eastern Europe.[7][22][24]

Culture

Identity

The Ursari are among the groups of Roma to practice endogamy, alongside the Kalderash, the Lovari and the Gabori;[7][9][23] many Mechkara believe refer to themselves as "Vlachs" or "Romanians", and tend to consider themselves distinct from other Roma.[7] For the Ursari community at large, the rules upheld specifically prevent sexual contact with the gadjo and favor arranged marriages,[9] but seem to have allowed for intermarriage inside the Boyash community at large.[7] They are also among the few Roma groups to allow the marriage of young teenagers, although this custom is falling out of use.[6][9][23]

Eastern Orthodox by tradition (belonging to either the Romanian Orthodox or Bulgarian Orthodox churches),[7][23] many Ursari are adhering to Protestant movements such as Pentecostalism.[23] The Ursari in Serbia and Italy are members of the Serbian Orthodox Church.[8] Days of the calendar traditionally upheld as holidays by the Ursari include February 1, the first day of fair seasons, and the Orthodox Calendar November 30 feast of Saint Andrew (whom the Ursari people regard as a patron saint).[23] In the early first decade of the 21st century, the New Testament was being translated into the Ursari form of the Balkan Romani language.[3]

Ursari and bears

As an aspect of their trade, the Ursari have established and encouraged various folk beliefs and customs involving the bear; these include displaying bears in the courtyards of village houses as a means to protect livestock from attack by smaller wild animals, and călcătura ursului ("the bear step") or călcătura lui Moş Martin ("Old Boy Martin's step", based on a common nickname for the animal), which involves allowing bears to tread on a person's back (in the belief that it can ensure the fertility of young people or chase away evil spirits).[9][23][35]

The latter custom was very popular among Romanians, who viewed it as a folk remedy for back pain; welcoming Ursari into one's household to perform the task formed part of a string of events leading to the celebration of Easter, or part of customs ushering in Christmas and the New Year's Eve.[14][36]

Among the members of the Ursari community who manufactured objects of bone, it became widespread to treat the material with bear fat, a luxury good which, they believed, helped make the products in question more durable.[9] The fat was also being sold to Romanians as medicine to combat rheumatism and skeletal disorders, together with bear hairs that were a popular amulet.[14]

The practices associated with bear training have again been the focus of animal welfare groups ever since the 1990s, and were subject to an adverse campaign in The International Herald Tribune.[37] While noting the use of crude methods of training, Isabel Fonseca, who visited the Ursari in places such as Bolintin Deal and Stara Zagora Province, argued that, as the main bread-winners for Ursari families, bears were also the recipients of care, attention, and proper feeding.[24]

Several artists have portrayed Romani bear trainers and their animals in their work. Among them are the Romanian painter and graphic artist Theodor Aman and the American sculptor Paul Wayland Bartlett (whose 1888 Bohemian Bear Tamer bronze is on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City).

Music

While, ever since the 1850s, many Ursari musicians have contributed to Lăutari culture to the point where they have grown separated from their original environment,[9] traditional Ursari music survived as a separate genre; fused with electronic music, was popularized in early 21st century Romania by the Shukar Collective project.[38]

A chant used by Ursari trainers has passed into Romanian folklore as a nursery rhyme. It includes the lyrics:

|

Joacă, joacă Moș Martine, |

Dance, dance Old Boy Martin, |

A longer version of it was still being sung by the Ursari in Bacău County by 2007:

|

Foaie verde pădureț, |

Green leaf of crabapple, |

Belarusian rock-band Hair Peace Salon dedicated its song "Gypsy" from the album Split Before, Together Now to all "gypsies and bears."[39]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 (in Romanian) Centrul de Documentare şi Informare despre Minorităţile din Europa de Sud-Est, Romii din România, at the Erdélyi Magyar Adatbank, retrieved June 25, 2007

- ↑ Balkan Romani at Ethnologue.com, retrieved June 23, 2007

- 1 2 3 "Roma – Sub Ethnic Groups", at Rombase, retrieved June 23, 2007

- 1 2 3 Angus M. Fraser, The Gypsies, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, 1995, p.45-48, 226. ISBN 0-631-19605-6

- ↑ Lucassen, p.84, 86, 90

- 1 2 (in Romanian) Mihai Surdu, Sarcina şi căsătoria timpurie în cazul tinerelor roma Archived 2007-09-26 at the Wayback Machine, at UNICEF Romania, retrieved June 24, 2007

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Elena Marushiakova, Vesselin Popov, "Ethnosocial Structure of the Roma of Bulgaria", in The Patrin Web Journal: Romani Culture and History, retrieved June 24, 2007

- 1 2 3 4 (in Italian) Scheda progetto per l'impiego di volontari in Servizio Civile in Italia. Pijats Romanò Archived 2007-09-26 at the Wayback Machine, at the Centro Servizi per il Volontariato, retrieved June 24, 2007

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 (in Romanian) Delia Grigore, Curs de antropologie şi folclor rrom Archived 2008-04-23 at the Wayback Machine, hosted by Romanothan, retrieved June 24, 2007

- ↑ "Ayjides".

- 1 2 Neagu Djuvara, Între Orient şi Occident. Ţările române la începutul epocii moderne, Humanitas, Bucharest, 1995, p.267-269. ISBN 973-28-0523-4

- 1 2 3 (in Romanian) Emmanuelle Pons, De la robie la asimilare, p.18-19, at the Erdélyi Magyar Adatbank, retrieved June 23, 2007

- 1 2 3 4 5 Édouard Antoine Thouvenel, La Hongrie et la Valachie, Arthus Betrand, Paris, 1840, p.242-243

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 (in Romanian) Eugen Şendrea, "Distracţii de tîrgoveţi", in Ziarul de Bacău, May 26, 2007; retrieved June 24, 2007

- 1 2 Henry Baerlein (ed.), Romanian Oasis: A Further Anthology on Romania and Her People, Frederick Muller Ltd., London, 1948, p.202

- ↑ Fonseca, p.181

- ↑ (in Romanian) Mihail Kogălniceanu, Dezrobirea ţiganilor, ştergerea privilegiilor boiereşti, emanciparea ţăranilor (wikisource)

- 1 2 3 Constantin C. Giurescu, Istoria Bucureștilor. Din cele mai vechi timpuri pînă în zilele noastre, Editura Pentru Literatură, Bucharest, 1966, p.380. OCLC 1279610

- ↑ Lucassen, p.81-82, 89

- ↑ Nikola Rašić, Romanies in Netherlands Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine, at the KPC Groep Archived 2018-06-28 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved June 23, 2007

- ↑ Lucassen, p.82, 83

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Carneys and Street Artists", at Rombase, retrieved June 23, 2007

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Improving Education for Roma Children Archived 2007-09-26 at the Wayback Machine, hosted by the Center Education 2000+ Archived 2007-08-27 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved June 23, 2007

- 1 2 3 4 Fonseca, p.182

- 1 2 3 (in Romanian) Petre Petcuț, Samudaripenul (Holocaustul) rromilor în România Archived 2007-07-10 at the Wayback Machine, at Idee Communication Archived 2012-02-06 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved June 24, 2007

- ↑ Fonseca, p.149

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 (in Romanian) Margareta Fleșner, Ioaneta Vintileanu, "Conflictele locale din județul Giurgiu și implicarea forțelor de poliție", in Ioaneta Vintileanu, Gábor Ádám, Poliția și comunitățile multiculturale din România, hosted by Centrul de Resurse pentru Diversitate Etnoculturală, retrieved June 25, 2007

- 1 2 Fonseca, p.150

- ↑ Fonseca, p.148-155

- 1 2 (in Romanian) Magda Bărăscu, "Romii din Bolintin vînează fondurile UE", in Evenimentul Zilei, April 20, 2005, hosted by Euractiv.ro Archived 2007-06-22 at the Wayback Machine; retrieved June 25, 2007

- ↑ Fonseca, p.150-151

- ↑ Fonseca, p.152

- 1 2 Fonseca, p.154

- ↑ Fonseca, p.153-154

- ↑ călcá in Alexandru Ciorănescu, Dicţionarul etimologic român, Universidad de la Laguna, Tenerife, 1958-1966; retrieved September 11, 2007

- ↑ (in Romanian) Costin Anghel, "Vechi datini populare", in Jurnalul Naţional, March 6, 2006; retrieved June 24, 2007

- ↑ Fonseca, p.180

- ↑ Shukar Collective site Archived 2007-06-30 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved June 23, 2007

- ↑ Вітушка, Воля; Сідун, Юра (2009-01-29). "Завершаны музычны конкурс Bandscan:Belarus: з канцэртамі ў Стакгольм едзе менскі The Toobes" [The music competition Bandscan:Belarus has been finished: The Toobes is going to travel with concerts in Stockholm] (in Belarusian). generation.by. Archived from the original on 2018-10-17. Retrieved 2018-12-24.

- Isabel Fonseca, Bury Me Standing. The Gypsies and Their Journey, Vintage Departures, New York, 1995. ISBN 0-679-73743-X

- Ewa Kocój, Zanikająca profesja? Cygańscy niedźwiednicy w Rumunii (Ursari) – historia i metody tresury – ,Studia Romologica”, 2015, 8, pp. 146–164, http://studiaromologica.pl/roczniki/8-2015/

- Ewa Kocój, Ignorance versus degradation? The profession of Gypsy bear handlers and managing of inconvenient intangible cultural heritage. Case study – Romania (I), ,Zarządzanie w Kulturze”, 2016, z. 3, pp. 263–283, http://www.ejournals.eu/Zarzadzanie-w-Kulturze/Tom-17-2016/17-3-2016/art/7409/

- Ewa Kocój, Paweł Lechowski, Cyganie w Rumuni (z dziejów tematu w wiekach XV-XIX), [in:] We wspólnocie narodów i kultur. W kręgu relacji polsko-rumuńskich. Materiały z sympozjum, red. St. Jakimowska, E. Wieruszewska, Suczawa 2008, pp. 374–387.

- Leo Lucassen, The Power of Definition. Stigmatisation, Minoritisation, and Ethnicity Illustrated by the History of the Gypsies in the Netherlands, at the Erdélyi Magyar Adatbank, retrieved June 25, 2007