| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Valcyte, Valcip, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a605021 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 60% |

| Protein binding | 1–2% |

| Metabolism | Hydrolysed to ganciclovir |

| Elimination half-life | 4 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

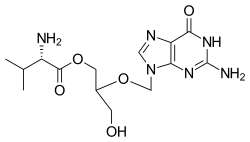

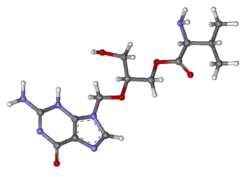

| Formula | C14H22N6O5 |

| Molar mass | 354.367 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Valganciclovir, sold under the brand name Valcyte among others, is an antiviral medication used to treat cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection in those with HIV/AIDS or following organ transplant.[3] It is often used long term as it only suppresses rather than cures the infection.[3] Valganciclovir is taken by mouth.[3]

Common side effects include abdominal pain, headaches, trouble sleeping, nausea, fever, and low blood cell counts.[3] Other side effects may include infertility and kidney problems.[3] When used during pregnancy, it causes birth defects in some animals.[3] Valganciclovir is the L-valyl ester of ganciclovir and works when broken down into ganciclovir by the intestine and liver.[3]

Valganciclovir was approved for medical use in 2001.[4] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[5][6] In 2017, a generic version was approved.[7]

Medical uses

Adults

Valganciclovir is commonly used for treatment of cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis (eye infection may cause blindness) in people who have acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).[8] Valganciclovir is also used to prevent cytomegalovirus disease in people who have received a heart, kidney, or kidney-pancreas transplant and who have a chance of getting CMV disease.[8] Overall, valganciclovir works by preventing the spread of CMV disease or slowing the growth of CMV.

Children

Valganciclovir is used for the prevention of CMV disease in people following kidney transplant (4 months to 16 years of age) and heart transplant (1 month to 16 years of age) at high risk.[2]

Side effects

Valganciclovir is commonly associated with vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and headache.[2] Other side effects include fever, trouble sleeping, peripheral neuropathy, and retinal detachment.[2]

Of note, the FDA issued several black box warnings concerning potential severe toxicities. These include:

- Blood toxicities: neutropenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia[2]

- Impairment of fertility (based on animal studies only)[2]

- Fetal toxicities (based on animal studies only)[2]

- Mutagenesis and carcinogenesis (based on animal studies only)[2]

Drug interactions

While not studied in people, it can be assumed that interactions will be similar as those with ganciclovir, since valganciclovir is converted into ganciclovir in the body.[2] Zidovudine may decrease the concentration of ganciclovir, and together the drugs can cause anemia and neutropenia.[2] Probenecid can increase the concentration of ganciclovir, which could increase the chances of ganciclovir toxicity.[2] People with kidney problems could have an increase in both mycophenolate mofetil and ganciclovir concentrations when both drugs are taken together.[2] Ganciclovir can also increase the concentration of didanosine.[2]

Mechanism of action

Valganciclovir is a prodrug for ganciclovir, which is a synthetic analog of 2′-deoxy-guanosine. Its structure is the same as ganciclovir, except for the addition of a L-valyl ester at the 5' end of the incomplete deoxyribose ring. The valine increases both the absorption of the drug in the intestines, as well as the bioavailability of the drug once it is absorbed. The L-valyl ester is cleaved by esterases in the intestines and the liver, leaving ganciclovir to be absorbed by the virus-infected cells.[9]

Ganciclovir is first phosphorylated to ganciclovir monophosphate by a viral thymidine kinase encoded by the cytomegalovirus (CMV) upon infection.[10] Human cellular kinases further phosphorylate the molecule to create ganciclovir diphosphate, then ganciclovir triphosphate.[10] These kinases are present in 10-fold greater concentrations in CMV or herpes simplex virus (HSV)-infected cells compared to uninfected human cells, allowing ganciclovir triphosphate to concentrate in infected cells.[10]

Ganciclovir triphosphate is a competitive inhibitor of deoxyguanosine triphosphate (dGTP).[10] It is incorporated into viral DNA and preferentially inhibits viral DNA polymerases more than cellular DNA polymerases. Ganciclovir triphosphate serves as a poor substrate for chain elongation. Once incorporated into viral DNA due to its structure similarity to dGTP, chain termination occurs once a single nucleotide is added to the distal hydroxyl group of the incomplete deoxyribose ring of ganciclovir.[11]

Pharmacokinetics

- Oral bioavailability is approximately 60%. Fatty foods significantly increase the bioavailability and the peak level in the serum.

- It takes about 2 hours to reach maximum concentrations in the serum.

- Valganciclovir is eliminated as ganciclovir in the urine, with a half-life of about 4 hours in people with normal kidney function.

- The mechanism of this drug is activation via a viral protein kinase HCMV UL97 and subsequent phosphorylation by cellular kinases. The phosphotransferase enzyme can likewise activate valganciclovir.

Chemistry

The synthesis of valganciclovir has been reviewed. Many routes use ganciclovir as a starting material.[12]

Society and culture

Price and patent status

Roche's Valcyte is protected by patent. However a generic version manufactured by Japanese-owned Indian company Daiichi-Ranbaxy was found by the District Court of New Jersey, USA not to infringe Roche's patent.[13] In November 2014, FDA approved generics by two manufacturers.[14]

The price of a four-month course of valganciclovir from Roche is about US$8,500 in high-income countries, $6,000 in India. However, the valganciclovir patent was rejected by the Indian Patent Office[15] in 2010, although Roche may appeal the rejection.

Names

Also known as Cymeval, Valcyt, Valixa, Darilin, Rovalcyte, Patheon, and Syntex.[16]

References

- 1 2 "Valcyte® (valganciclovir hydrochloride)". Australian Product Information. MedAdvisor International Pty Ltd. Retrieved 2023-08-10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Valcyte- valganciclovir tablet, film coated Valcyte- valganciclovir hydrochloride powder, for solution". DailyMed. U.S. National Library of Medicine. 9 August 2018. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Valganciclovir Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 29 November 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ Long SS, Pickering LK, Prober CG (2012). Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Disease. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1502. ISBN 978-1-4377-2702-9. Archived from the original on 2016-11-29.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2021). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ↑ "Generic Valcyte Availability". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 17 March 2017. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- 1 2 "Valganciclovir: MedlinePlus Drug Information". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2016-11-10. Retrieved 2016-11-10.

- ↑ Lukacova V, Goelzer P, Reddy M, Greig G, Reigner B, Parrott N (November 2016). "A Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Model for Ganciclovir and Its Prodrug Valganciclovir in Adults and Children". The AAPS Journal. 18 (6): 1453–1463. doi:10.1208/s12248-016-9956-4. PMID 27450227. S2CID 22702960.

- 1 2 3 4 Matthews T, Boehme R (2016-08-01). "Antiviral activity and mechanism of action of ganciclovir". Reviews of Infectious Diseases. 10 (Suppl 3): S490–S494. doi:10.1093/clinids/10.supplement_3.s490. PMID 2847285.

- ↑ Chen H, Beardsley GP, Coen DM (December 2014). "Mechanism of ganciclovir-induced chain termination revealed by resistant viral polymerase mutants with reduced exonuclease activity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (49): 17462–17467. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11117462C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1405981111. PMC 4267342. PMID 25422422.

- ↑ Vardanyan R, Hruby V (2016). "34: Antiviral Drugs". Synthesis of Best-Seller Drugs. pp. 709–713. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-411492-0.00034-1. ISBN 978-0-12-411492-0. S2CID 75449475.

- ↑ Babu G (16 October 2009). "US Court rules Ranbaxy's generic valganciclovir does not infringe Roche's Valcyte patent" (PDF). Pharmabiz. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04.

- ↑ "First-Time Generic Drug Approvals". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. November 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-11-16.

- ↑ "Victory for access to medicine as Valganciclovir patent rejected in India - news - MSF UK". Médecins Sans Frontières MSF (Doctors Without Borders). March 3, 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-03-03.

- ↑ "Valganciclovir". Drugs.com. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

External links

- "Valganciclovir". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.