Varlam Cherkezishvili | |

|---|---|

ვარლამ ჩერქეზიშვილი | |

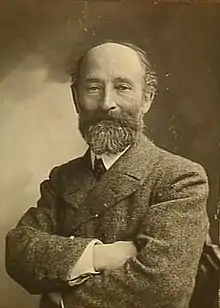

Cherkezishvili c. 1905, taken by Nadar | |

| Born | 15 September 1846 |

| Died | 18 August 1925 (aged 78) |

| Nationality | Georgian |

| Movement | |

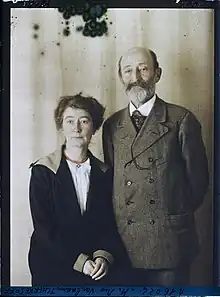

| Spouse |

Freda Rupertus (m. 1899–1925) |

| Family | Cherkezishvili |

Varlam Nikolozi dze Cherkezishvili (Georgian: ვარლამ ნიკოლოზის ძე ჩერქეზიშვილი;[lower-alpha 1] 15 September 1846 – 18 August 1925) was a Georgian aristocrat and journalist involved in Georgian anarchist and national liberation movements.

Biography

Born in Kakheti in 1846, Cherkezishvili went to study in St. Petersburg, where he Dmitry Karakozov and joined Sergey Nechayev's nihilist group, becoming one of Georgia's first "professional revolutionaries". For his radical activities, Cherkezishvili was tried and sentenced to penal labour in Siberia, but he escaped in 1876 and fled to Switzerland.[2] In exile, he initially became involved with the Russian emigre movement, but split with them over his support for Georgian independence. This attracted him towards anarchism, due to its promise of self-determination for small nations, and he became a disciple of the Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin.[3] But his new-found anarchism also brought him into disagreement with other Georgian nationalists, such as Noe Zhordania, who he met in London in 1897.[4]

In 1903, Kropotkin and Cherkezishvili joined Georgy Gogelia's Bread and Freedom group, established in order to distribute anarchist literature clandestinely throughout the Russian Empire.[5] They quickly attracted a following and received numerous requests for more literature to be sent, gaining particular popularity in areas of the Pale of Settlement, such as Poland and Ukraine.[6] Cherkezishvili himself contributed to the publication, penning a critical analysis of Marxism.[7] In the wake of the Russian Revolution of 1905, Cherkezishvili, Gogelia and Kropotkin helped launched Mikheil Tsereteli's anarchist periodical Nobati in Tbilisi, contributing critiques of state socialism in an attempt to bring the Georgian revolutionary movement over to anarchism.[8] But during their brief period of conflict with the social democrats, to which a young Joseph Stalin contributed critiques of anarchism, they were unable to build a popular organisation and the Georgian anarchist movement slowly diminished.[9]

In 1907, Cherkezishvili, alongside Peter Kropotkin, Rudolf Rocker and Alexander Schapiro, helped organize the London Anarchist Red Cross, in order to aid political prisoners of the Russian Empire.[10] The organisation collected money and clothing, which they sent to prisoners in Russia, and circulated petitions in protest against the political repression in the Russian Empire.[11] That year, Cherkezishvili himself presented a petition for Georgian independence to the Hague Peace Conference, but it failed to garner any support.[3] During this period, Cherkezishvili and Kropotkin often spoke at the Federation of Jewish Anarchists' Jubilee Street Club.[12]

When Kropotkin expressed support for the Allies of World War I, he was backed up by Cherkezishvili. In 1916, Cherkezishvili and Kropotkin, along with Jean Grave, Charles Malato, Christian Cornelissen, James Guillaume and ten others, signed the Manifesto of the Sixteen in support of the Allied war effort.[13] For this, they were fiercely criticised by anarchists of the internationalist position, including their former associate Georgy Gogelia, who denounced them as "anarcho-patriots".[14]

With the outbreak of the Russian Revolution in 1917, Cherkezishvili returned to Georgia, where he reunited with Gogelia and gradually fell out of contact with Kropotkin.[15] Following the deaths of Kropotkin and Gogelia,[16] Cherkezishvili returned to London, where he died in 1925.[17]

Notes

- ↑ Also known by the Russian: Варлаам Николаевич Черкезов, romanized: Varlaam Nikolaevich Cherkezov; as during the time of the Russian Empire, it was common for Georgian names to be Russified.[1]

References

- ↑ Lang 1962, p. 281n62.

- ↑ Lang 1962, pp. 119–120.

- 1 2 Lang 1962, p. 120.

- ↑ Lang 1962, p. 128.

- ↑ Avrich 1971, pp. 38–39; Lang 1962, p. 120.

- ↑ Avrich 1971, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Avrich 1971, p. 39; Lang 1962, p. 120.

- ↑ Lang 1962, p. 172.

- ↑ Lang 1962, pp. 172–173.

- ↑ Avrich 1971, p. 113.

- ↑ Avrich 1971, pp. 113–114.

- ↑ Avrich 1971, p. 40n15.

- ↑ Avrich 1971, p. 116.

- ↑ Avrich 1971, pp. 116–117.

- ↑ Avrich 1971, pp. 136–137.

- ↑ Avrich 1971, p. 236.

- ↑ Avrich 1971, p. 236; Lang 1962, pp. 119–120.

Bibliography

- Avrich, Paul (1971) [1967]. The Russian Anarchists. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00766-7. OCLC 1154930946.

- Lang, David Marshall (1962). "A Georgian anarchist". A Modern History of Soviet Georgia. Grove Press. LCCN 62-13057. OCLC 398597.

Further reading

- Bakhtadze, Mikhail; Vachnadze, Merab; Guruliwork, Vakhtang (2014). История Грузии (с древнейших времен до наших дней) (in Russian). Tbilisi: Izdatelʹstvo Intelekti. p. 91. ISBN 9789941446849. OCLC 891380302. Archived from the original on 17 April 2013.

- Creagh, Ronald (24 April 2015). "L'autre prince anarchiste : Warlaam Tcherkesoff". Research on Anarchism (in French). Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- Dubovik, Anatoly. "Периодические издания анархистов в России и в эмиграции. 1900—1916". Russian socialists and anarchists after October 1917 (in Russian). Russian Humanitarian Science Foundation. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- Gogatishvili, Mikheil (2015). "Dictatorship and Theory (Varlam Cherkezishvili's Critic of Social-Democratic Movement)". 3rd Eurasian Multidisciplinary Forum. European Scientific Institute. pp. 154–158. ISBN 978-608-4642-46-6 – via Academia.edu.

- Larané, André (2 June 2019). "Alexandre II Romanov (1818-1881), De l'espoir à la tragédie". Hérodote (in French). ISSN 1776-2987. LCCN 82642448. OCLC 470212254.

- Maitron, Jean (2022-10-02), "TCHERKESOFF Warlaam Dzon Aslanovic [ou Tcherkezishvili, Cerkezov, Cherkesov, Tcherkezov]", Dictionnaire des Anarchistes (in French), Paris: Maitron/Editions de l'Atelier, retrieved 2022-10-30

- Mitchell, Ryan Robert (2009). "Anarchism, Georgia". In Ness, Immanuel (ed.). The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest. pp. 1–2. doi:10.1002/9781405198073.wbierp1659. ISBN 9781405198073.

- Nettlau, Max (15 October 1925). "Tcherkesov". Plus Loin (in French). Paris (8). OCLC 803044836. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- Nettlau, Max (15 November 1925). "Tcherkesov". Plus Loin (in French). Paris (9). OCLC 803044836. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- Nettlau, Max (1996). A Short History of Anarchism. Freedom Press. ISBN 978-0900384899. OCLC 37529250.

- Nikolaevskii, B. (1926). "Varlaam Nikolaevich Cherkezov (1846-1925)". Katorga i Ssylka (in Russian). No. 4. Moscow: Vses. Obšč. pp. 222–232. OCLC 649337235.

- Nolan, Dieter; Grotz, Florian; Hartmann, Christof (2001). Elections in Asia and the Pacific: A Data Handbook, Volume I: Middle East, Central Asia, and South Asia. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 395. ISBN 0191530417.

- Ostrowski, Marius S. (2021). Eduard Bernstein on Socialism Past and Present: Essays and Lectures on Ideology. Springer Nature. p. 157. ISBN 978-3-030-50484-7.

- R.D. (5 October 2012). "TCHERKESOV Warlaam [TCHERKESICHVILI]". Dictionnaire international des militants anarchistes (in French). Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- "10". Анархисты] Политические партии России: история и современность. Russian Political Encyclopedia. Moscow: ROSSPEN. 2000. pp. 210–226.

- "Varlaam Cherkezov". L'Éphéméride anarchiste. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

External links

- "Georgian independence petition 'found' in Oxford", BBC News, 25 May 2018