Saint Benjamin of Petrograd | |

|---|---|

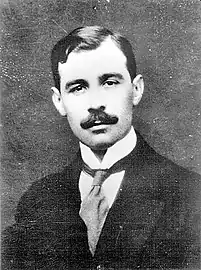

.jpg.webp) Benjamin (Kazansky), Metropolitan of Petrograd and Gdov | |

| Hieromartyr | |

| Born | 29 April [O.S. 17 April] 1873 Olonets Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 13 August [O.S. 31 July] 1922 Kovalevsky Forest, Soviet Union |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodoxy |

| Canonized | 4 April 1992, Danilov Monastery, Moscow, Russian Federation by Russian Orthodox Church |

| Major shrine | Nikolskoe Cemetery of the Alexander Nevsky Lavra |

| Feast | 31 July Sunday on or following 25 January (the celebration of the Synaxis of the new Russian martyrs and confessors)[1] |

Benjamin of Petrograd (Russian: Вениамин Петроградский, Veniamin Petrogradsky, 29 April [O.S. 17 April] 1873 – 13 August [O.S. 31 July] 1922), born Vasily Pavlovich Kazansky (Russian: Василий Павлович Казанский), was a hieromartyr, a bishop in the Russian Orthodox Church and eventually Metropolitan of Petrograd and Gdov from 1917 to 1922. He was martyred, executed by a firing squad by Soviet authorities. In April 1992 Benjamin was glorified (canonized) by the Russian Orthodox Church together with several other martyrs, including Archimandrite Sergius (Shein), Professor Yury Novitsky, and John Kovsharov (a lawyer), who were executed with him.[1]

Background and education

Benjamin was born to a priestly family in the pogost (village) of Nimenskii in the Andreevskii volost of the Kargopolsky Uyezd near Arkhangelsk in the Olonets Governorate in the northwest of the Russian Empire.

He graduated from the Olonets Theological Seminary in 1893 and earned his candidate of theology degree from the St. Petersburg Spiritual Academy in 1897, defending a thesis on Archbishop Arcadius of Olonets' anti-heretical activities. In 1895 he was tonsured a monk and given the name Benjamin; later that year he was ordained a hierodeacon (deacon-monk) and the following year he was ordained a hieromonk (priest-monk).

Following his graduation he taught sacred scripture at the Riga Theological Seminary (1897–1898) following which he was inspector of the Kholm Theological Seminary (1898–1899) and the St. Petersburg Spiritual Academy (1899–1902). In 1902 he became rector of the Samara Theologocal Seminary and he was bestowed with the rank of archimandrite. In 1905 he became rector of the St. Petersburg Spiritual Academy.

Vicar Bishop

On 6 February [O.S. 24 January] 1910 Benjamin was consecrated Bishop of Gdov, a vicar bishop of the diocese of St. Petersburg. Metropolitan Antonii (Vadkovskii) of St. Petersburg and Ladoga officiated at the installment in the Alexander Nevsky Lavra in St. Petersburg. Benjamin often served in the churches of the poorest and most remote suburbs of the capital and led the annual Easter and Christmas divine services at Putilovsky and Obukhovsky factories of St. Petersburg, and organized the charitable foundation of the Mother of God for the Care of Abandoned Women. He was known as "the indefatigable bishop".

Metropolitan of Petrograd

After the arrest and deposition of Metropolitan Pitirim (Onkova) on 15 March [O.S. 2 March] 1917, Benjamin administered the Petrograd diocese as vicarial Bishop of Gdov. On 6 June [O.S. 24 May] of that year, he was democratically elected by the clergy and the people to the archbishopric of Petrograd and Ladoga, the first bishop popularly elected in the Russian church. On 30 June [O.S. 17 June] his title was changed to Archbishop of Petrograd and Gdov by decree of the Holy Synod,[2] and on 26 August [O.S. 13 August] he was elevated to metropolitan.

While the Church tried to maintain a neutral stance during the Russian Civil War, and Benjamin was one of the few people in Russia with no interest in politics,[3] the Russian Orthodox Church and Soviet State had diametrically opposite world views and the church was viewed as dangerously counter-revolutionary by the Soviet authorities.[4]

The real conflict, however, came out into the open during in the Russian famine of 1921 when the Soviet authorities announced the confiscation of Church valuables, allegedly to pay for famine relief. The Russian Orthodox Church agreed to this, but declined to hand over certain valuables of religious or historic significance.[5]

Metropolitan Benjamin was willing to donate the Church's valuables voluntarily, but would not accept the plundering and desecration of Churches implemented by the Bolsheviks. On 6 March Benjamin met with a commission formed to help the starving that agreed to his voluntary dispersal of funds controlled by the parishes. Newspapers of that time praised Benjamin and his clergy for their charitable spirit.[3] In April, Benjamin reached an agreement with Petrograd party officials to hand over certain valuables and to allow parishioners to substitute their own valuables for other church valuables of historic or religious significance.[6] However, the Politburo in Moscow overruled the decision and declared that the confiscation of Church property would continue. In response, protesters gathered in Petrograd, shouting and throwing stones at Party officials who were raiding Orthodox churches.[3]

Catholic memoirist Martha Almedingen later recalled, "In most cases, [confiscation] raids were accompanied by wild outbursts of most abject and vulgar profanation, hardly ever checked by the higher officials who were invariably present at such proceedings."[7]

Arrest and show trial

The final conflict for Metropolitan Benjamin began when the State-controlled Living Church tried to wrest control away from Patriarch Tikhon and the established hierarchy.[3]

In May 1922, Alexander Vvedensky and Vladimir Krasnitsky travelled to Petrograd seeking to convert Metropolitan Benjamin to the State-controlled Living Church and to thus take over control of the See Petrograd.[8] While secretly confident of the result, Metropolitan Benjamin offered to put the issue before his clergy and laity at the Alexander Nevsky Lavra. First, both sides would speak and then the people would vote.[9]

On Sunday 28 May 1922, after everyone gathered, Vvedensky spoke first, "Brothers and sisters, up to now we have been subject to the Tsar and the Metropolitans. But now we are free, and we ourselves must rule the people and the Church. More than 1,900 years have already passed since it was written for us that the Lord Jesus Christ was born from the Virgin Mary and is the Son of God. But that is not true. We recognize the existence of the God of Sabbaoth, about whom our whole Bible and all the prophets have written... But Jesus Christ is not God. He was simply a very clever man. And it is impossible to call Mary - who was born of a Jewish tribe and herself gave birth to Jesus - the Mother of God and Virgin. And so now we have all recognized the existence of God, that is the God of Sabbaoth, and we must all be united; both Jews and Catholics must be a living people's church."[9]

Fellow senior Living Church clergyman Vladimir Krasnitsky then spoke, denouncing the practice of infant baptism instead of adult baptism. Krasnitsky also praised the Living Church's rejection of the veneration of Saints and their relics, as well as their further break with Orthodox canon law by allowing Bishops to marry and both the divorce and remarriage of priests.[9]

The assembled Orthodox clergy and laity were horrified by these statements by the Living Church clergymen and, after Metropolitan Benjamin with difficulty quieted the outraged audience, he first accused the Living Church of reviving the 4th century heresy of Arianism and then anathematized their clergy and laity alike as both schismatics and heretics. In response, an outraged Vvedensky quietly slipped out a side door and informed a small army of GPU agents waiting outside, who burst into the meeting and, despite the audience's efforts to protect him, arrested Metropolitan Benjamin,[10] who was placed under house arrest pending trial.[11]

Instead of backing down, Metropolitan Benjamin issued a 29 May pastoral letter to every parish and strictly forbade Vvedensky or any other Living Church priests from administering the sacraments within his Diocese until they had first repented before Patriarch Tikhon.[12]

For this reason, an outraged Vvedensky made a point of accompanying the GPU agents who arrested the Metropolitan at his residence.[3][11] Vvedensky's presence at the Metropolitan's arrest was widely compared with the behavior of Judas Iscariot at the arrest of Jesus Christ.[12] Benjamin was tried by a revolutionary tribunal with ten other defendants from 10 June to 5 July. Whenever Benjamin entered the courtroom for his trial, people stood up for him and he blessed them.[13]

According to historian Paul Gabel, "The prosecutor was arch-atheist Peter Krasikov, who, like Krylenko in the Moscow Trial, saw conspiracy rather than genuine religious passion as the cause of the violence surrounding churches. He had orders from Moscow to discredit the Church, and the verdicts were foregone conclusions. At one point in the trial he shouted that the entire Church was a subversive organization and everybody in it should be thrown in prison."[14]

In a subsequent interview in Paris with Constantin de Grunwald, the Metropolitan's Jewish defence attorney, S. Gurovich, recalled, "I felt that I had a genuine Saint sitting behind me on the accused's bench."[15]

According to Paul Gabel, "The defendants, as before, cited the power of Church canons. They also argued that priests had actually attempted to calm the angry crowds that were surrounding and protecting the churches. But when three witnesses came forward to testify for Benjamin they were promptly arrested, thus effectively ending the defense's case. When Benjamin spoke in his own defense, he only offered he had always acted alone and was never an enemy of the people. He had dedicated his whole life to them, and they had repaid him with love."[14]

In his closing arguments, Gurovich warned the Soviet State, "If the Metropolitan perishes for his faith, for his limitless devotion to the believing masses, he will become more dangerous for Soviet power than now... the unfailing historical law warns us that faith grows, strengthens, and increases on the blood of Martyrs."[14]

Before the verdict was announced, Metropolitan Benjamin addressed the court, "Regardless of what my sentence will be, no matter what you decide, life or death, I will lift up my eyes reverently to God, Cross myself and affirm, 'Glory to Thee my Lord; glory to Thee for everything!'"[16]

The defendants were found guilty of being, "dangerous and uncompromising foes of the Republic" and condemned to the supreme penalty of death by shooting.[15] The defendants were given a chance to speak, and Benjamin addressed the court saying it grieved him to be called an enemy of the people whom he had always loved and to whom he had dedicated his life.

Gurovich added, "There are no proofs of guilty. There are no facts. There is not even and indictment... What will history say?"[15]

Meanwhile, the Living Church-controlled Church Administration passed its own sentence, stripping Metropolitan Benjamin, Novitsky, and Kovsharov of their priestly and monastic ranks and reducing them to members of the laity.[11]

Martyrdom

The sentences of six of the defendants were later commuted by the Politburo, though not of Metropolitan Benjamin and the others seen as the main leaders of alleged anti-Soviet agitation.[13]

According to Paul Gabel, "A rumor circulated that Benjamin had already been executed. When a crowd gathered around the prison where he was being held, demanding he be shown to them if he were still alive. GPU agents fired into the assemblage and it disbanded. When it formed again, the warden was forced to make a deal: He allowed three members of the gathering to come inside, where they ascertained that Benjamin indeed was still among the living."[15]

During the night of 12–13 August [O.S. 30–31 July] 1922 after having been shaved and dressed in rags so that the firing squad would not know that they were shooting members of the Orthodox clergy, Benjamin and those with him, Archimandrite Sergius, Yury Novitsky, and John Kovsharov,[3] were executed in the eastern outskirts of Petrograd, at the Porokhov Station of the Irinovskaya Railroad (a narrow-gauge railroad built to bring peat into the city for heating that starts in the Bolshaya Okhta district of St. Petersburg, across the Neva River from the Smolny Institute and ending at Vsevolozhsk 24 kilometres (15 mi) east of the city.)

New York Herald correspondent Captain Francis McCullagh attempted to make the world aware of the trial and execution of Metropolitan Benjamin, but his every attempt, "was suppressed by the censor". Although McCullagh was more successful in raising global awareness of the 1923 Moscow show trial of Archbishop Jan Cieplak, Monsignor Konstanty Budkiewicz, and Exarch Leonid Feodorov, Captain McCullagh later recalled, "Bishop Benjamin was a martyr quite as much as Mgr. Budkiewicz was. And as I have shown, he was not the only martyr of the Orthodox Church who suffered on this occasion."[17]

Benjamin's cenotaph is located in the Nikolskoe Cemetery of the Alexander Nevsky Lavra; the Decree of Canonization directs for Benjamin and others "That their precious remains, should they have been found, shall be considered holy relics."[1]

Quotes

- "It is difficult, hard to suffer, but according to the measure of my sufferings, consolation abounds from God... [When one gives oneself over wholly to the will of God] man abounds in consolation and does not even feel the greatest sufferings; filled as he is in the midst of sufferings by an inner peace, he draws others to sufferings so that they should imitate that condition in which the happy sufferer finds himself."[18]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Proclamation of the Holy Council of Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church of Canonization", Retrieved 2012-10-25

- ↑ «Церковныя Вѣдомости, издаваемыя при Святѣйшемъ Правительствующемъ Сѵнодѣ». 3 июня 1917, No. 22—23, стр. 148 (годовая пагинация)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Lives of the Saints — July 31 — Hieromartyr Benjamin the Metropolitan of Petrograd and Gdovsk", Retrieved 2012-10-25

- ↑ Roslof, Edward E. (2002). Red Priests: Renovationism, Russian Orthodoxy, & Revolution, 1905–1946. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- ↑ Roslof, Red Priests, 42;

- ↑ Roslof, Red Priests, 49.

- ↑ Paul Gabel (2005), And Created Lenin: Marxism vs. Religion in Russia, 1917-1929, Prometheus Books. Page 388.

- ↑ Roslof, Red Priests, 54–55, 62.

- 1 2 3 Paul Gabel (2005), And Created Lenin: Marxism vs. Religion in Russia, 1917-1929, Prometheus Books. Page 247.

- ↑ Paul Gabel (2005), And Created Lenin: Marxism vs. Religion in Russia, 1917-1929, Prometheus Books. Pages 247-248.

- 1 2 3 Paul Gabel (2005), And Created Lenin: Marxism vs. Religion in Russia, 1917-1929, Prometheus Books. Page 248.

- 1 2 Roslof (2002), p. 62.

- 1 2 Roslof, Red Priests, 65.

- 1 2 3 Paul Gabel (2005), And Created Lenin: Marxism vs. Religion in Russia, 1917-1929, Prometheus Books. Page 227.

- 1 2 3 4 Paul Gabel (2005), And Created Lenin: Marxism vs. Religion in Russia, 1917-1929, Prometheus Books. Page 228.

- ↑ Paul Gabel (2005), And Created Lenin: Marxism vs. Religion in Russia, 1917-1929, Prometheus Books. Page 225.

- ↑ Francis McCullagh (1924), The Bolshevik Persecution of Christianity, London. Page 52.

- ↑ Paul Gabel (2005), And Created Lenin: Marxism vs. Religion in Russia, 1917-1929, Prometheus Books. Page 51.

Other Literature

- "Дело" митрополита Вениамина (Петроград, 1922 г.). М., 1991

- Очерки истории Санкт-Петербургской епархии. СПб., 1994. С. 237-238

- Manuil (Lemeљevskij). "Die russischen orthodoxen Bischöfe von 1893 bis 1965": Bio-Bibliogr. Erlangen, 1981. T. 2. S. 142–145.