| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Avelox, Vigamox, Moxiflox, others |

| Other names | Moxifloxacine; BAY 12-8039 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a600002 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous, eye drops |

| Drug class | Antibiotic (fluoroquinolone) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 86%[2] |

| Protein binding | 47%[2] |

| Metabolism | Glucuronide and sulfate conjugation; CYP450 system not involved[3] |

| Elimination half-life | 12.1 hours[2] |

| Excretion | Urine, feces |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.129.459 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

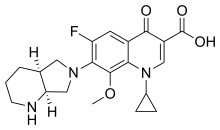

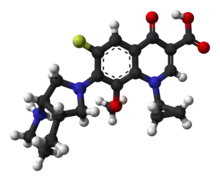

| Formula | C21H24FN3O4 |

| Molar mass | 401.438 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Moxifloxacin is an antibiotic, used to treat bacterial infections,[4] including pneumonia, conjunctivitis, endocarditis, tuberculosis, and sinusitis.[4][5] It can be given by mouth, by injection into a vein, and as an eye drop.[5]

Common side effects include diarrhea, dizziness, and headache.[4] Severe side effects may include spontaneous tendon ruptures, nerve damage, and worsening of myasthenia gravis.[4] Safety of use in pregnancy and breastfeeding is unclear.[6] Moxifloxacin is in the fluoroquinolone family of medications.[4] It usually kills bacteria by blocking their ability to duplicate DNA.[4]

Moxifloxacin was patented in 1988 and approved for use in the United States in 1999.[7][8] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[9]

Medical uses

Moxifloxacin treats a number of infections, including respiratory-tract infections, cellulitis, anthrax, intra-abdominal infections, endocarditis, meningitis, and tuberculosis.[10]

In the United States, moxifloxacin is licensed for the treatment of acute bacterial sinusitis, acute bacterial exacerbation of chronic bronchitis, community-acquired pneumonia, complicated and uncomplicated infections of the skin and of the skin structure, and complicated intra-abdominal infections.[11] In the European Union, it is licensed for acute bacterial exacerbations of chronic bronchitis, non-severe community-acquired pneumonia, and acute bacterial sinusitis. On the basis of its investigation into reports of rare but severe cases of liver toxicity and skin reactions, the European Medicines Agency recommended in 2008 that the use of the oral (but not the intravenous) form of moxifloxacin be restricted to infections in which other antibacterial agents cannot be used or have failed.[12] In the United States, the marketing approval does not contain these restrictions, though the label contains prominent warnings of skin reactions.

The initial approval by the Food and Drug Administration of the United States (December 1999)[13] encompassed these indications:

- Acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis

- Acute bacterial sinusitis

- Community acquired pneumonia

Additional indications approved by the Food and Drug Administration:

- April 2001: Uncomplicated skin and skin-structure infections[14]

- May 2004: Community-acquired pneumonia caused by multidrug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae[15]

- June 2005: Complicated skin and skin-structure infections[16]

- November 2005: Complicated intra-abdominal infections[17]

The European Medicines Agency has advised that, for pneumonia, acute bacterial sinusitis, and acute exacerbations of COPD, it should only be used when other antibiotics are inappropriate.[18][19]

Oral and intravenous moxifloxacin have not been approved for children. Several drugs in this class, including moxifloxacin, are not licensed by the Food and Drug Administration for use in children, because of the risk of permanent injury to the musculoskeletal system.[20][21][22] Moxifloxacin eye drops are approved for conjunctival infections caused by susceptible bacteria.[23]

Recently, alarming reports of moxifloxacin resistance rates among anaerobes have been published. In Austria 36% of Bacteroides have been reported to be resistant to moxifloxacin,[24] while in Italy resistance rates as high as 41% have been reported.[25]

Susceptible bacteria

A broad spectrum of bacteria is susceptible, including the following:

- Staphylococcus aureus

- Staphylococcus epidermidis

- Streptococcus pneumoniae

- Haemophilus influenzae

- Klebsiella spp.

- Moraxella catarrhalis

- Enterobacter spp.

- Mycobacterium spp.

- Bacillus anthracis

- Mycoplasma genitalium[26]

- Borrelia Burgdoferi (found to be effective in vitro) [27]

Adverse effects

Rare but serious adverse effects that may occur as a result of moxifloxacin therapy include irreversible peripheral neuropathy, spontaneous tendon rupture and tendonitis,[28] hepatitis, psychiatric effects (hallucinations, depression), torsades de pointes, Stevens–Johnson syndrome and Clostridium difficile-associated disease,[29] and photosensitivity/phototoxicity reactions.[30][31]

Several reports suggest the use of moxifloxacin may lead to uveitis.[32]

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Exposure of the developing fetus to quinolones, including levofloxacin, during the first-trimester is not associated with an increased risk of stillbirths, premature births, birth defects, or low birth weight.[33] There is limited data about the appearance of moxifloxacin in human breastmilk. Animal studies have found that moxifloxacin appears in significant concentration in breastmilk.[34] Decisions as to whether to continue therapy during pregnancy or while breast feeding should take the potential risk of harm to the fetus or child into account, as well as the importance of the drug to the well-being of the mother.[35]

Contraindications

Only two listed contraindications are found within the 2008 package insert:

- "Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): Although not observed with moxifloxacin in preclinical and clinical trials, the concomitant administration of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug with a fluoroquinolone may increase the risks of CNS stimulation and convulsions."[36]

- "Moxifloxacin is contraindicated in persons with a history of hypersensitivity to moxifloxacin, any member of the quinolone class of antimicrobial agents, or any of the product components."[36]

Though not stated as such within the package insert, ziprasidone is also considered to be contraindicated, as it may have the potential to prolong QT interval. Moxifloxacin should also be avoided in patients with uncorrected hypokalemia, or concurrent administration of other medications known to prolong the QT interval (antipsychotics and tricyclic antidepressants).[37]

Moxifloxacin should be used with caution in patients with diabetes, as glucose regulation may be significantly altered.[37]

Moxifloxacin is also considered to be contraindicated within the pediatric population, pregnancy, nursing mothers, patients with a history of tendon disorder, patients with documented QT prolongation,[38] and patients with epilepsy or other seizure disorders. Coadministration of moxifloxacin with other drugs that also prolong the QT interval or induce bradycardia (e.g., beta-blockers, amiodarone) should be avoided. Careful consideration should be given in the use of moxifloxacin in patients with cardiovascular disease, including those with conduction abnormalities.[37]

Children and adolescents

The safety of moxifloxacin in human patients under age 18 has not been established. Animal studies suggest a risk of musculoskeletal harm in juveniles.[35]

Interactions

Moxifloxacin is not believed to be associated with clinically significant drug interactions due to inhibition or stimulation of hepatic metabolism. Thus, it should not, for the most part, require special clinical or laboratory monitoring to ensure its safety.[39] Moxifloxacin has a potential for a serious drug interaction with NSAIDs.[40]

The combination of corticosteroids and moxifloxacin has increased potential to result in tendonitis and disability.[41]

Antacids containing aluminium or magnesium ions inhibit the absorption of moxifloxacin. Drugs that prolong the QT interval (e.g., pimozide) may have an additive effect on QT prolongation and lead to increased risk of ventricular arrhythmias. The international normalised ratio may be increased or decreased in patients treated with warfarin.[40]

Overdose

"In the event of acute overdose, the stomach should be emptied and adequate hydration maintained. ECG monitoring is recommended due to the possibility of QT interval prolongation. The patient should be carefully observed and given supportive treatment. The administration of activated charcoal as soon as possible after oral overdose may prevent excessive increase of systemic moxifloxacin exposure. About 3% and 9% of the dose of moxifloxacin, as well as about 2% and 4.5% of its glucuronide metabolite are removed by continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis, respectively." (Quoting from 29 December 2008 package insert for Avelox)[36]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Moxifloxacin is a broad-spectrum antibiotic that is active against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. It functions by inhibiting DNA gyrase, a type II topoisomerase, and topoisomerase IV,[42] enzymes necessary to separate bacterial DNA, thereby inhibiting cell replication.

Pharmacokinetics

About 52% of an oral or intravenous dose of moxifloxacin is metabolized via glucuronide and sulfate conjugation. The cytochrome P450 system is not involved in moxifloxacin metabolism, and is not affected by moxifloxacin.[3] The sulfate conjugate (M1) accounts for around 38% of the dose, and is eliminated primarily in the feces. Approximately 14% of an oral or intravenous dose is converted to a glucuronide conjugate (M2), which is excreted exclusively in the urine. Peak plasma concentrations of M2 are about 40% those of the parent drug, while plasma concentrations of M1 are, in general, less than 10% those of moxifloxacin.[36]

In vitro studies with cytochrome (CYP) P450 enzymes indicate that moxifloxacin does not inhibit 80 CYP3A4, CYP2D6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, or CYP1A2, suggesting that moxifloxacin is unlikely to alter the pharmacokinetics of drugs metabolized by these enzymes.[36][3]

The pharmacokinetics of moxifloxacin in pediatric subjects have not been studied.[36]

The elimination half-life of moxifloxacin is 11.5 to 15.6 hours (single-dose, oral).[43] About 45% of an oral or intravenous dose of moxifloxacin is excreted as unchanged drug (about 20% in urine and 25% in feces). A total of 96 ± 4% of an oral dose is excreted as either unchanged drug or known metabolites. The mean (± SD) apparent total body clearance and renal clearance are 12 ± 2 L/h and 2.6 ± 0.5 L/h, respectively.[43] The CSF penetration of moxifloxacin is 70% to 80% in patients with meningitis.[44]

Chemistry

Moxifloxacin monohydrochloride is a slightly yellow to yellow crystalline substance.[36] It is synthesized in several steps, the first involving the preparation of racemic 2,8-diazabicyclo[4.3.0]nonane which is then resolved using tartaric acid. A suitably derivatised quinolinecarboxylic acid is then introduced, in the presence of DABCO, followed by acidification to form moxifloxacin hydrochloride.[45]

History

Moxifloxacin was first patented (United States patent) in 1991 by Bayer A.G., and again in 1997.[46] Avelox was subsequently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in the United States in 1999 to treat specific bacterial infections.[7] Ranking 140th within the top 200 prescribed drugs in the United States for 2007,[47] Avelox generated sales of $697.3 million worldwide.[48]

Moxifloxacin is also manufactured by Alcon as Vigamox.[49]

Patent

A United States patent application was made on 30 June 1989, for Avelox, Bayer A.G. being the assignee, which was subsequently approved on 5 February 1991. This patent was scheduled to expire on 30 June 2009. However, this patent was extended for an additional two and one half years on 16 September 2004, and as such was not expected to expire until 2012.[50] Moxifloxacin was subsequently (ten years later) approved by the FDA for use in the United States in 1999. At least four additional United States patents have been filed regarding moxifloxacin hydrochloride since the 1989 United States application,[46][51] as well as patents outside of the US.

Society and culture

Regulatory actions

Regulatory agencies have taken actions to address certain rare but serious adverse events associated with moxifloxacin therapy.

Based on its investigation into reports of rare but severe cases of liver toxicity and skin reactions, the European Medicines Agency recommended in 2008 that the use of the oral (but not the IV) form of moxifloxacin be restricted to infections in which other antibacterial agents cannot be used or have failed.[12] Similarly, the Canadian label includes a warning of the risk of liver injury.[52]

The U.S. label does not contain restrictions similar to the European label, but a carries a "black box" warning of the risk of tendon damage and/or rupture and warnings regarding the risk of irreversible peripheral neuropathy.[53]

Generic equivalents

In 2007, the U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware held that two Bayer patents on Avelox are valid and enforceable, and infringed by Dr. Reddy's ANDA for a generic version of Avelox.[54][55] The district court sided with Bayer, citing the Federal Circuit's prior decision in Takeda v. Alphapharm[56] as "affirming the district court's finding that defendant failed to prove a prima facie case of obviousness where the prior art disclosed a broad selection of compounds, any one of which could have been selected as a lead compound for further investigation, and defendant did not prove that the prior art would have led to the selection of the particular compound singled out by defendant." According to Bayer's press release[54] announcing the court's decision, it was noted that Teva had also challenged the validity of the same Bayer patents at issue in the Dr. Reddy's case. Within Bayer's first-quarter 2008 stockholder's newsletter[57] Bayer stated that they had reached an agreement with Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., the adverse party, to settle their patent litigation with regard to the two Bayer patents. Under the settlement terms agreed upon, Teva would obtain a license to sell its generic moxifloxacin tablet product in the U.S. shortly before the second of the two Bayer patents expires in March 2014. In Bangladesh, it is available with brand name of Optimox.

References

- ↑ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- 1 2 3 Zhanel GG, Fontaine S, Adam H, Schurek K, Mayer M, Noreddin AM, et al. (2006). "A Review of New Fluoroquinolones : Focus on their Use in Respiratory Tract Infections". Treatments in Respiratory Medicine. 5 (6): 437–465. doi:10.2165/00151829-200605060-00009. PMID 17154673. S2CID 26955572.

- 1 2 3 World Health Organization (2008). Guidelines for the Programmatic Management of Drug-resistant Tuberculosis. World Health Organization. pp. 189–. ISBN 978-92-4-154758-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Moxifloxacin Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- 1 2 British national formulary : BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. pp. 408, 757. ISBN 9780857111562.

- ↑ "Moxifloxacin Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- 1 2 "Details for NDA:021085". DrugPatentWatch. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- ↑ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 501. ISBN 9783527607495.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ "Avelox". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ↑ "Documents" (PDF). accessdata.fda.gov.

- 1 2 "Press release" (PDF). Europa (web portal).

- ↑ "Application letter" (PDF). accessdata.fda.gov. 1999. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ↑ "Approval of supplements" (PDF). accessdata.fda.gov. 2001. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ↑ "Application letter" (PDF). accessdata.fda.gov. 2004. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ↑ "Approval of supplements" (PDF). accessdata.fda.gov. 2005. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ↑ "Application letter" (PDF). accessdata.fda.gov. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ↑ "Moxifloxacin: increased risk of life-threatening liver reactions and other serious risks". gov.uk. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ↑ "European Medicines Agency recommends restricting the use of oral moxifloxacin-containing medicines" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 24 July 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2009. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- ↑ "SYNOPSIS" (PDF). Retrieved 29 January 2009.

- ↑ Karande SC, Kshirsagar NA (February 1992). "Adverse drug reaction monitoring of ciprofloxacin in pediatric practice". Indian Pediatrics. 29 (2): 181–188. PMID 1592498.

- ↑ Dolui SK, Das M, Hazra A (2007). "Ofloxacin-induced reversible arthropathy in a child". Journal of Postgraduate Medicine. 53 (2): 144–145. doi:10.4103/0022-3859.32220. PMID 17495385.

- ↑ "Center for drug evaluation and research Application number 21-598" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 15 April 2005. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- ↑ König E, Ziegler HP, Tribus J, Grisold AJ, Feierl G, Leitner E (April 2021). "Surveillance of Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Anaerobe Clinical Isolates in Southeast Austria: Bacteroides fragilis Group Is on the Fast Track to Resistance". Antibiotics. 10 (5): 479. doi:10.3390/antibiotics10050479. PMC 8143075. PMID 33919239.

- ↑ Principe L, Sanson G, Luzzati R, Aschbacher R, Pagani E, Luzzaro F, Di Bella S (August 2022). "Time to reconsider moxifloxacin anti-anaerobic activity?". Journal of Chemotherapy. 35 (4): 367–368. doi:10.1080/1120009X.2022.2106637. PMID 35947127. S2CID 251470489.

- ↑ Unemo M, Jensen JS (March 2017). "Antimicrobial-resistant sexually transmitted infections: gonorrhoea and Mycoplasma genitalium". Nature Reviews. Urology. 14 (3): 139–152. doi:10.1038/nrurol.2016.268. PMID 28072403. S2CID 205521926.

- ↑ Pothineni VR, Wagh D, Babar MM, Inayathullah M, Solow-Cordero D, Kim KM, et al. (1 April 2016). "Identification of new drug candidates against Borrelia burgdorferi using high-throughput screening". Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 10: 1307–1322. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S101486. PMC 4827596. PMID 27103785.

- ↑ Albrecht R (28 July 2004). "NDA 21-085/S-024, NDA 21-277/S-019" (PDF). Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 31 July 2009.

- ↑ Albrecht R (31 May 2007). "NDA 21-085/S-036, NDA 21-277/S-030" (PDF). Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 31 July 2009.

- ↑ Albrecht R (15 February 2008). "NDA 21-085/S-038, NDA 21-277/S-031" (PDF). Division of Special Pathogen and Transplant Products. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 31 July 2009.

- ↑ DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES (28 February 2008). "NDA 21-085/S-014, S-015, S-017" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- ↑ "Risk for Uveitis With Oral Moxifloxacin". JAMA Ophthalmology online. 2 October 2014.

- ↑ Ziv A, Masarwa R, Perlman A, Ziv D, Matok I (March 2018). "Pregnancy Outcomes Following Exposure to Quinolone Antibiotics - a Systematic-Review and Meta-Analysis". Pharmaceutical Research. 35 (5): 109. doi:10.1007/s11095-018-2383-8. PMID 29582196. S2CID 4724821.

- ↑ Balfour JA, Lamb HM (January 2000). "Moxifloxacin: a review of its clinical potential in the management of community-acquired respiratory tract infections". Drugs. 59 (1): 115–139. doi:10.2165/00003495-200059010-00010. PMID 10718103. S2CID 195694147.

- 1 2 "merck.com" (PDF).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bayer (December 2008). "AVELOX (moxifloxacin hydrochloride) Tablets AVELOX I.V. (moxifloxacin hydrochloride in sodium chloride injection)" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration (FDA). p. 19. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Moxifloxacin". University of Maryland Medical Center. 2009. Archived from the original on 7 March 2009. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ↑ "Microsoft Word - Rote Hand Brief Avalox an BfArM.doc" (PDF). Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ↑ Nightingale CH (March 2000). "Moxifloxacin, a new antibiotic designed to treat community-acquired respiratory tract infections: a review of microbiologic and pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic characteristics". Pharmacotherapy. 20 (3): 245–256. doi:10.1592/phco.20.4.245.34880. PMID 10730681. S2CID 11448163.

- 1 2 U.S. Food and Drug Administration (15 December 1999). "RE: NDA # 21-085 Avelox (moxifloxacin hydrochloride) Tablets MACMIS # 8577" (PDF). Letter to Martina Ziska. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2009. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

- ↑ Albrecht R (16 May 2002). "NDA 21-085/S-012" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- ↑ Drlica K, Zhao X (September 1997). "DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 61 (3): 377–392. doi:10.1128/mmbr.61.3.377-392.1997. PMC 232616. PMID 9293187.

- 1 2 "Drug card for Moxifloxacin (DB00218)". Canada: DrugBank. 19 February 2009. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ↑ Alffenaar JW, van Altena R, Bökkerink HJ, Luijckx GJ, van Soolingen D, Aarnoutse RE, van der Werf TS (October 2009). "Pharmacokinetics of moxifloxacin in cerebrospinal fluid and plasma in patients with tuberculous meningitis". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 49 (7): 1080–1082. doi:10.1086/605576. hdl:2066/79494. PMID 19712035.

- ↑ Peterson U (2006). "Quinolone Antibiotics: The Development of Moxifloxacin". In Fischer J, Ganellin CR (eds.). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 338–342. ISBN 9783527607495.

- 1 2 "Inventors/Applicants". patentlens.net. 3 October 2006. Archived from the original on 21 February 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- ↑ Lamb E (1 May 2008). "Top 200 Prescription Drugs of 2007". Pharmacy Times. Archived from the original on 7 February 2009. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- ↑ "EU agency recommends restricting moxifloxacin use". Reuters. 24 July 2008. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- ↑ "Alcon's Newest Antibiotic, Vigamox Ophthalmic Solution, Earns FDA Approval". Infection Control Today. Alcon. 22 June 2003. Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- ↑ "Patent form" (PDF). uspto.gov. 1 February 1991. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ↑ US 4990517 A (Feb 1991) Petersen et al. See US 5051509 A (Sep 1991) Nagano et al. See US 5059597 A (Oct 1991) Petersen et al. See US 5395944 A (Mar 1995) Petersen et al. See US 5416096 A (May 1995) Petersen et al. See

- ↑ "Updated Labelling for Antibiotic Avelox (Moxifloxacin) Regarding Rare Risk of Severe Liver Injury". Health Canada. 22 March 2010.

Information Update: 2010-42

- ↑ Albrecht R (3 October 2008). "NDA 21-085/S-040, NDA 21-277/S-034" (PDF). Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 31 July 2009.

- 1 2 Bayer AG (6 November 2007). "Ruling in Bayer's favor over Avelox patents". Bayer. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ↑ "Opinion form" (PDF). orangebookblog.com. 5 October 2007. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ↑ "United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit" (PDF). uscourts.gov. 28 June 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 August 2009. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ↑ Bayer AG (24 April 2008). "Risk Report". Bayer. Archived from the original on 9 March 2009. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

External links

- "Moxifloxacin". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Moxifloxacin hydrochloride". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.