Vivian Phillipps | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of Parliament for Edinburgh West | |

| In office 15 November 1922 – 29 October 1924 | |

| Preceded by | John Gordon Jameson |

| Succeeded by | Ian MacIntyre |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 13 April 1870 Beckenham, Kent, England |

| Died | 16 January 1955 (aged 84) Leigh, Kent, England |

| Political party | Liberal |

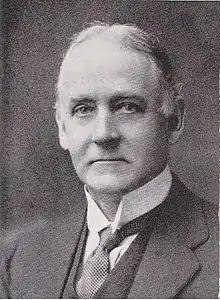

Henry Vivian Phillipps (13 April 1870 – 16 January 1955) was a British teacher, lawyer and Liberal politician.

Family and education

Phillipps was born in Beckenham, Kent, the son of Henry Mitchell Phillipps. In 1883, he went to Charterhouse School[1] and in 1886 he travelled to Heidelberg in southern Germany to study for three years, returning as a fluent speaker of the German language.[2] In 1890, Phillipps went to Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, obtaining his bachelor's degree in Modern Languages tripos in 1893.[3] In 1899, he married Edinburgh woman Agnes Ford, and they couple had a son and two daughters.[1]

Career

Phillipps' first employment was as a teacher of German at Fettes College in Edinburgh.[4] While there he wrote a text-book, A Short Sketch of German Literature for Schools, published in 1895. He left Fettes in 1905,[5] deciding to opt for a career in the law. In 1907 he was called to the Bar at Lincoln's Inn[5] and practised as a member of the Northern Circuit. From 1915 he served as a Justice of the Peace in Kent and became Vice-Chairman of the Bench in 1931.[6] He was Chairman of the West Kent Quarter Sessions between 1933 and 1945.[1]

Politics

Parliamentary candidate

A convinced Liberal, Phillipps first tried to enter Parliament at Blackpool in 1906 and then at Maidstone in both the January and December 1910 general elections.[7] In 1918 he was the Liberal candidate at Rochdale but as a supporter of H H Asquith he was not a recipient of the Lloyd George Coalition Government coupon which went instead to his Conservative opponent Alfred Law, who won with a healthy majority of 7,847 votes.

Political secretary

Between 1912 and 1916, Phillipps was appointed to be private secretary to Thomas McKinnon Wood, the Scottish Secretary.[8] He continued briefly in that post under Wood's successor Harold Tennant. Tennant was the brother of Margot Asquith (née Tennant), the wife of the prime minister. When Asquith was replaced as prime minister by Lloyd George in December 1916, he asked Phillipps to become his private secretary, a post he held between 1917 and 1922.[1] He gained a reputation at this time as being the most implacable opponent of Lloyd George of the circle around Asquith.[7]

Member of Parliament

Phillipps finally managed to enter the House of Commons at the 1922 general election for the constituency of Edinburgh West. In a straight fight with the sitting Conservative Member of Parliament John Gordon Jameson, Phillipps won the seat, albeit by the narrow margin of 666 votes. He held the seat at the 1923 general election this time in a three-cornered contest with Tory and Labour opponents, increasing his majority to 2,232, when some commentators had forecast he would lose.[9]

Liberal Whip

After the 1922 general election, there were a number of attempts to bring about the reunion of the Asquith and Lloyd George factions within the Liberal Party.[10]) Asquith was by now back in the House of Commons having won a by-election at Paisley in 1920 but he and Lloyd George were initially cool on the possibility of reunion [11] The problem of reunion spilled over into internal party appointments. In 1919, Asquith had selected George Rennie Thorne, the MP for Wolverhampton East as his Chief Whip. Asquith was not in Parliament at this time and the remaining independent Liberals wanted James Myles Hogge as Whip, so Asquith appointed him to be Thorne's colleague.[12] Thorne resigned in 1923 and Asquith took the opportunity to replace Hogge as well, immediately appointing Phillipps to the post of Chief Whip, even though as a newly elected MP he was inexperienced in Parliamentary terms. Moreover, Phillipps was known to be totally committed to his old chief and was perhaps not the right choice to lead the negotiations between the rival wings of the party as they struggled to come to an accommodation and towards an eventual reunion. Or perhaps he was exactly what Asquith and the official party wanted. One historian comments that the appointment of Phillipps underlined the reluctance of the official Liberals to renew their connection with the former prime minister [13] while another suggests that Asquith sacked Hogge and deliberately appointed Phillipps in order to thwart reunion at that time.[14] The 1923 general election helped the situation, as it was called on the issue of protectionism and tariff reform by prime minister Stanley Baldwin and Liberals of all shades were able to come together in support of the traditional policy of free trade. However, there were other issues to be resolved before formal reunion could be achieved, notably the question of access for the former independent Liberals to monies in the Lloyd George fund, the sizeable treasure chest which he had amassed over the years including by the sale of honours during his time in 10 Downing Street.[15] Further difficulties emerged with the formation of the first Labour government in January 1924. The Liberals, who held the Balance of power in the House of Commons agreed to allow Labour to take office, causing further disagreements within the party. Phillipps, as Chief Whip, had to issue a statement at one point officially denying a split between Asquith and Lloyd George on the question of turning out the Baldwin government.[16] On occasions the party's MPs were split in Parliamentary votes [17] and it was a disastrous miscalculation on a Liberal amendment to a Conservative censure motion on the Campbell case which actually led to the downfall of the government against Liberal wishes.[18] Phillipps presided over all this as Chief Whip.

1924 General Election

Like so many other Liberal MPs, Phillipps was unable to overcome the swing to the right which occurred at the 1924 general election. The electorate was coming to see the political system as a left-right battle between the principal challengers on those wings of British politics, Labour and Conservative. There was little room for the Liberals in a system which discriminated against third parties and in a tight three-way contest in Edinburgh West Phillipps lost his seat to the Conservatives.[19] Overall the Liberal Party's Parliamentary strength was reduced to 40 seats. Phillipps stood again in Edinburgh West at the 1929 general election but found himself out of step again with Lloyd George over the issue of reducing unemployment by state intervention. The impression given to the electorate was of a still divided Liberal Party. It was again a reasonably close three-cornered contest but Phillipps came third and he decided not to try for re-election Parliament again.[19]

Other political and public appointments

Phillipps served as Chairman of the Liberal Party Organisation from 1925–27 and was one of the secretaries to the Liberal Council, a group of Liberal grandees opposed to Lloyd George.[5] These appointments proved difficult for Phillipps because Asquith was out of the House of Commons again after losing Paisley in 1924 and agreed to go to the House of Lords in 1925, playing a diminishing role in the party, eventually resigning as leader in 1926.[20] Lloyd George assumed the leadership. Questions of money and organisation proved onerous.[21] Phillipps chaired a fund raising initiative called the 'Million Fighting Fund' [22] but the appeal was a disaster and he was forced to resign from the party's Administrative Committee.[23] The Liberal Council was set up by Phillipps and a number of other distinguished Liberals with the object of rallying those party members who opposed Lloyd George and his money and to supply sympathetic constituency associations with speakers, literature and candidates.[24] Phillipps never overcame his distrust of Lloyd George and his enmity towards him. When Conservative newspapers began trying to uncover damaging information about the Lloyd George Fund and the sale of honours Phillipps was one of their prime sources.[7]

Less controversially perhaps, Phillipps was a member of the West Kent Unemployment Appeal Tribunal, 1934–40 and the Kent Agricultural Wages Committee, 1935–40. He also served on the Board of Visitors at Maidstone Convict Prison.[1]

Autobiography

In 1943 Phillipps published his autobiography My Days and Ways; published by Pillans & Wilson of Edinburgh and printed "for private circulation".[25] Douglas has described it as a "useful record to how matters looked to a devoted Asquithian".[26]

Death

Phillipps died at his home at Upper Kennards, Leigh, Kent near Tonbridge in Kent on 16 January 1955 aged 84. [5]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Who was Who, OUP 2007

- ↑ Roy Douglas, Vivian Phillipps in Brack et al., Dictionary of Liberal Biography; Politico's, 1998 p295

- ↑ "Phillipps, Henry Vivian (PHLS890HV)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ↑ Douglas, op cit, p295

- 1 2 3 4 The Times, 18 January 1955

- ↑ Douglas, op cit p297

- 1 2 3 Philip Williamson, Henry Vivian Phillipps in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography; OUP 2004-08

- ↑ The Times, 13 June 1912

- ↑ The Times, 8 December 1923

- ↑ Chris Cook, The Age of Alignment: Electoral Politics in Britain 1922-1929; Macmillan, 1975 p.89

- ↑ David Dutton, A History of the Liberal Party in the Twentieth Century; Palgrave Macmillan, 2004 p90

- ↑ The Times, 13 February 1923

- ↑ David Powell, British Politics 1910-1935: The Crisis of the Party System; Routledge, 2004 p122-123

- ↑ Cook, op cit pp 89-90 & 96

- ↑ G. R. Searle, The Liberal Party: Triumph and Disintegration, 1886-1929; Palgrave, 2001 p146

- ↑ The Times, 19 April 1924

- ↑ The Times, 8 April 1924

- ↑ Roy Douglas, History of the Liberal Party, 1895-1970; Sidgwick & Jackson ,1971 pp 179-180

- 1 2 F. W. S. Craig, British Parliamentary Elections Results, 1918-1949, Political Reference Publications, 1969, p. 584

- ↑ The Times, 15 October 1926

- ↑ The Times, 27 November 1925

- ↑ The Times, 3 February 1925

- ↑ Trevor Wilson, The Downfall of the Liberal Party, 1914-1935; Cornell University Press, 1966 p339

- ↑ Wilson op cit, pp339-340

- ↑ British Library catalogue; system number 002901786

- ↑ Douglas, in Dictionary of Liberal Biography; p297