| Walker Process Equipment, Inc. v. Food Machinery & Chemical Corp. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued October 12–13, 1965 Decided December 6, 1965 | |

| Full case name | Walker Process Equipment, Inc. v. Food Machinery & Chemical Corp. |

| Citations | 382 U.S. 172 (more) |

| Argument | Oral argument |

| Case history | |

| Prior | 335 F.2d 315 (7th Cir. 1964) |

| Holding | |

| That enforcement of a fraudulently procured patent violated the antitrust laws and provided a basis for a claim of treble damages if it caused a substantial anticompetitive effect. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinion | |

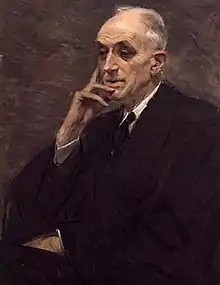

| Majority | Clark, joined by unanimous |

| Laws applied | |

| 15 U.S.C. §§ 1–7; 15 U.S.C. §§ 12–27; 29 U.S.C. §§ 52–53 | |

Walker Process Equipment, Inc. v. Food Machinery & Chemical Corp., 382 U.S. 172 (1965), was a 1965 decision of the United States Supreme Court that held, for the first time, that enforcement of a fraudulently procured patent violated the antitrust laws and provided a basis for a claim of treble damages if it caused a substantial anticompetitive effect.

Background

Food Machinery sued Walker for patent infringement for aeration equipment for sewage treatment systems. Walker filed a counterclaim for treble damages under the antitrust laws, asserting that Food Machinery had "illegally monopolized interstate and foreign commerce by fraudulently and in bad faith obtaining and maintaining . . . its patent ... well knowing that it had no basis for . . . a patent." Walker alleged that Food Machinery had fraudulently sworn to the Patent Office (in an oath that the patent statute requires of applicants) that it neither knew nor believed that its invention had been in public use in the United States for more than one year prior to filing its patent application when, in fact, Food Machinery was itself a party to such prior use. Walker further asserted that the existence of the patent damaged Walker by depriving it of business that it would have otherwise enjoyed.[1]

The district court granted Food Machinery's motion to dismiss the counterclaim, and the Seventh Circuit affirmed, on the grounds that no affirmative claim for relief existed based on fraud on the patent office. It was only a defense to an infringement claim.[2]

Ruling of Supreme Court

Majority opinion

.jpg.webp)

In an opinion by Justice Tom C. Clark, the Court reversed. It held: "We have concluded that the enforcement of a patent procured by fraud on the Patent Office may be violative of § 2 of the Sherman Act provided the other elements necessary to a § 2 case are present. In such event the treble damage provisions of § 4 of the Clayton Act would be available to an injured party."

The Court began by stating that proof that Food Machinery intentionally misrepresented facts to the patent office "would be sufficient to strip Food Machinery of its exemption from the antitrust laws" when it brought an infringement suit. By the same token, however, "Food Machinery's good faith would furnish a complete defense." This defense would apply to "an honest mistake as to the effect of prior installation upon patentability." [3]

But while there can be liability it is not automatic. To establish monopolization or attempt to monopolize a part of trade or commerce under § 2 of the Sherman Act:

[I]t would then be necessary to appraise the exclusionary power of the illegal patent claim in terms of the relevant market for the product involved. Without a definition of that market there is no way to measure Food Machinery's ability to lessen or destroy competition. It may be that the device—knee-action swing diffusers—used in sewage treatment systems does not comprise a relevant market. There may be effective substitutes for the device which do not infringe the patent. This is a matter of proof . . . .[4]

Nonetheless, Walker is entitled to an opportunity to prove its case:

The trial court dismissed its suit not because Walker failed to allege the relevant market, the dominance of the patented device therein, and the injurious consequences to Walker of the patent's enforcement, but rather on the ground that the United States alone may "annul or set aside" a patent for fraud in procurement. The trial court has not analyzed any economic data. Indeed, no such proof has yet been offered because of the disposition below. In view of these considerations, as well as the novelty of the claim asserted and the paucity of guidelines available in the decided cases, this deficiency cannot be deemed crucial. Fairness requires that on remand Walker have the opportunity to make its § 2 claims more specific, to prove the alleged fraud, and to establish the necessary elements of the asserted § 2 violation.[5]

Concurring opinion

Justice John Marshall Harlan II concurred. He wrote separately to emphasize the limits of the holding. No treble damage case would be established, he said, if:

- the antitrust claimant merely showed that the patent was obvious;

- there was fraudulent procurement, but the defendant had no knowledge of the fraud;

- the antitrust claimant failed to prove the remaining elements of a § 2 charge.[6]

Justice Harlan insisted that:

[T]o hold, as we do not, that private antitrust suits might also reach monopolies practiced under patents that for one reason or another may turn out to be voidable under one or more of the numerous technicalities attending the issuance of a patent, might well chill the disclosure of inventions through the obtaining of a patent because of fear of the vexations or punitive consequences of treble-damage suits. Hence, this private antitrust remedy should not be deemed available to reach § 2 monopolies carried on under a nonfraudulently procured patent.[7]

Subsequent developments

One of the points not developed in detail in the Walker Process opinion was what "the fraudulent procurement of a patent" means.[8] Because most Walker Process claims are brought by defendants accused of patent infringement, most such cases are now appealed to the Federal Circuit (since that court's formation in 1982), and thus that court has been enormously influential in subsequent developments of the Walker Process doctrine.[9] Another issue is what is enforcement—must there be an actual infringement suit or is a threat to a competitor or its customer sufficient?[10]

Pre-Federal Circuit cases

In Beckman Instrument, Inc. v. Chemtronics, Inc.[11] the Fifth Circuit held Beckman's patent claiming a polarographic cell for making quantitative analysis of blood invalid because of fraud on the Patent Office (later renamed the Patent & Trademark Office). The district court had upheld the patent as valid, although not infringed.[12] But the Fifth Circuit reversed because Beckman knew about a similar Stow device but decided not to disclose its existence to the Patent Office. The Fifth Circuit ruled that "Beckman had an 'uncompromising duty' of disclosure of the Stow reference to the Patent Office." According to the Fifth Circuit, the Stow device anticipated Beckman's device, so that the Beckman patent was invalid on two grounds: anticipation and fraudulent failure to disclose Stow when prosecuting the patent.[13] The court did not say whether Stow was closer than the prior art that the Patent Office considered, but it was close enough to anticipate. The Fifth Circuit said that there is a clear duty to disclose known prior art that is close to the claimed invention: ""[Ilt is clear that Beckman's patent employees understood the significance of Stow's invention and knew that it presented a serious threat to the validity of the patent they were trying to secure."[14] One of the things Beckman did to avoid the effect of Stow was to tailor its claims so that they did not directly cover the Stow device, but the court said this did not relieve Beckman of its duty of disclosure.

In Monsanto Co. v. Rohm and Haas Co.,[15] the Third Circuit addressed issues not discussed in Walker Process when invalidating a patent for fraud. Monsanto had persuaded the Patent Office to withdraw an obviousness rejection of a patent on a herbicide by submitting test data showing that the claimed compound (3,4-DCPA) had surprisingly superior herbicidal efficacy compared to compounds with a very similar molecular structure. Monsanto had tested a number of these compounds, some of which did have similar efficacy to that of 3,4-DCPA and some of which did not. Monsanto intentionally submitted to the Patent Office only the data showing lack of similar efficacy.

The Third Circuit rejected the argument that Monsanto was only putting its best foot forward and was therefore innocent of fraud. The court held that omitting such highly material information in a submission to the Office was equivalent to an affirmative misrepresentation that products with similar efficacy did not exist:

[A]n examination of the report permits, if not compels, the misleading inference that it constituted a complete and accurate analysis of all the testing instead of an edited version thereof. Concealment and nondisclosure may be evidence of and equivalent to a false representation, because the concealment or suppression is, in effect, a representation that what is disclosed is the whole truth.[16]

The court added, "Monsanto was obliged to disclose more information as to the herbicidal properties of related compounds to the Patent Office than it did." The reason is that "what is at issue is not merely a contest between the parties but a public interest" that spurious patents should not issue.

Federal Circuit case law on elements of Walker Process claim

The Federal Circuit decided, in Nobelpharma AB v. Implant Innovations, Inc.,[17] that the falsity triggering a Walker Process claim must be "material," meaning that the patent being enforced "would not have issued but for the misrepresentation or omission" that is challenged as fraudulent. In addition, the Federal Circuit held that "knowingly and willfully misrepresenting facts to the Patent Office" must be alleged, as Walker alleged in the Walker Process case,[18] and it must be shown by clear and convincing evidence.[19] These two elements of guilty knowledge and strong proof have been supplemented by the further two elements that the patentee must have acted with specific intent to deceive the PTO, and that the PTO justifiably relied on the misrepresentation or omission.[20] In addition to imposing these requirements, in 1998 the Federal Circuit announced that it would no longer follow the law of regional circuits in Walker Process cases, but would instead establish a uniform "patent case" rule for judging conduct before the PTO, based on Federal Circuit precedent.[21]

The Federal Circuit separated the affirmative defense aspect of a Walker Process claim from the antitrust counterclaim aspect by renaming the former "inequitable conduct," and for a time allowing a lesser standard of proof for inequitable conduct than Walker Process antitrust claims. In Dippin' Dots, Inc. v. Mosey,[22] the Federal Circuit held that the same intent evidence that established a defense of inequitable conduct did not support an antitrust counterclaim. The Federal Circuit declared, "To demonstrate Walker Process fraud, a claimant must make higher threshold showings of both materiality and intent than are required to show inequitable conduct."[23] It then held that the intent evidence against patentee Dippin' Dots was sufficient to support a conclusion of inequitable conduct but was insufficient for Walker Process fraud.[24] However, the Federal Circuit subsequently raised the legal standards for proving inequitable conduct so as to make it approximately equivalent to that for Walker Process fraud, in Therasense v. Becton, Dickinson & Co.[25] One commentator remarked that this change has led to a "virtual alignment of inequitable conduct and Walker Process fraud that was accomplished by Therasense."[26]

In reacting to the surge in the pleading of inequitable conduct and Walker Process fraud, the Federal Circuit remarked that "the habit of charging inequitable conduct in almost every major patent case has become an absolute plague."[27] This has suggested to some commentators that this reaction caused the Federal Circuit to tighten up the requirements for Walker Process and inequitable conduct claims and to favor greater leniency for patentees, as is described above.[28]

Handgards case

In Handgards, Inc. v. Ethicon, Inc.,[29] the Ninth Circuit decided that the enforcement of a knowingly invalid patent could give rise to antitrust liability.[30]

A similar type of claim is enforcing a valid patent against a defendant that the plaintiff knows is not infringing the patent.[31]

Criminal prosecution

In United States v. Union Camp Corp., the government brought a criminal case against a company that filed a patent infringement action against another company under a patent that it knew was invalid, because it had publicly sold the patented product more than a year before the filing of the patent application.[32]

It has been suggested that "a conspiracy to procure a patent by means of fraud constitutes, independently of the Sherman Act, a violation of the general federal conspiracy statute (18 U.S.C. § 371)."[33]

In United States v. Markham,[34] the defendant was indicted and convicted under the federal false statement statute (18 U.S.C. § 1001) for fraudulent patent procurement—"attempt[ing] to conceal from the Patent Office the true inventor of the process for which a patent was sought."[35] In that case one Klein, a business partner of the defendant Markham, invented a process for building houses. Markham and Klein fell out, and Markham filed a patent application falsely naming two other men as the inventors rather than Klein.[36] When the facts eventually came out, Markham was indicted and convicted; the court of appeals affirmed the conviction.[37]

References

The citations in this article are written in Bluebook style. Please see the talk page for more information.

- ↑ 382 U.S. at 173-74.

- ↑ 335 F. 2d 315 (7th Cir. 1964).

- ↑ 382 U.S. at 177.

- ↑ 382 U.S. at 177-78]

- ↑ 382 U.S. at 178.

- ↑ 382 U.S. at 179.

- ↑ 382 U.S. at 180.

- ↑ The quoted phrase appears at 382 U.S. at 176.

- ↑ All appeals from judgments in patent infringement cases go to the Federal Circuit. 28 U.S.C. § 1295(a)(1).

- ↑ Some lower courts have suggested, in dicta, that threats of enforcement are enough. See, e.g., Indium Corp. of Am. v. Semi-Alloys, Inc., 566 F. Supp. 1344, 1352-53 (N.D.N.Y. 1983) (holding that a Walker Process claimant "must at least be able to allege facts that indicate that the defendant has enforced, or has sought to enforce, or has threatened to enforce its fraudulently obtained patent against the plaintiff itself").

- ↑ 428 F.2d 555 (5th Cir. 1970).

- ↑ 160 U.S.P.Q. 619 (W.D. Tex. 1967).

- ↑ The Fifth Circuit has been criticized for "misapprehend[ing] the effect of a finding of fraud on the Patent Office." If Stow anticipated, then the patent is invalid for anticipation by Stow. But intentional deception of the Patent Office, it is said, does not invalidate a patent. Rather, it renders the patent permanently unenforceable for non-purgeable misuse. See Donald R. Dunner, James B, Gambrell, and Irving Kayton, Patent Law (1969-70), in [1970] Ann. Surv. Am. L. 395, 425 n.140 (1970).

- ↑ 428 F.2d at 565.

- ↑ 456 F.2d 592 (3d Cir. 1972).

- ↑ 456 F.2d at 599.

- ↑ 141 F.3d 1059, 1071 (Fed. Cir. 1998).

- ↑ 382 U.S. at 177.

- ↑ Nobelpharma, 141 F.3d at 1071.

- ↑ Nobelpharma, 141 F.3d at 1069-70; accord C.R. Bard, Inc. v. M3 Sys., Inc., 157 F.3d 1340, 1364 (Fed. Cir. 1998). As to specific intent see American Hoist & Derrick Co. v. Sowa & Sons, Inc., 725 F.2d 1350, 1368 (Fed. Cir. 1984) (stating that in a Walker Process claim based on attempt to monopolize, "a specific intent, greater than an intent evidenced by gross negligence or recklessness, is an indispensable element").

- ↑ Nobelpharma, 141 F.3d at 1067-68.

- ↑ 476 F.3d 1337 (Fed. Cir. 2007).

- ↑ Dippin' Dots, 476 F.3d at 1346.

- ↑ Dippin' Dots, 476 F.3d at 1349. The Federal Circuit said it was not enough for the jury to disbelieve the patentee's explanations; there must be affirmative evidence of intent to deceive.

- ↑ 649 F.3d 1276, 1289 (Fed. Cir. 2011).

- ↑ Gideon Mark and T. Leigh Anenson, Inequitable Conduct And Walker Process Claims After Therasense And The America Invents Act, 16 U. Pa. J. Bus. Law 361, 402 (2014).

- ↑ Burlington Indus. v. Dayco Corp., 849 F.2d 1418, 1422 (Fed. Cir. 1988). See also Melissa Feeney Wasserman, Limiting the Inequitable Conduct Defense, 13 Va. J.L. & Tech. 1, 8 (2008).

- ↑ See, e.g., Wasserman, at 13.

- ↑ 601 F.2d 986 (9th Cir. 1979).

- ↑ See Handgards, Inc. v. Ethicon, 743 F.2d 1282, 1289 (9th Cir. 1984) (upholding treble damage jury verdict).

- ↑ See Loctite Corp. v. Ultraseal Ltd., 781 F.2d 861, 877 (Fed. Cir. 1985) (applying the Handgards bad faith standard to situation where patentee knew there was no infringement but nonetheless enforced patent).

- ↑ 1969 Trade Cas. ¶ 72,689 (E.D. Va. 1969) (consent decree). In that case the company's patent counsel warned the company's president of the problem and suggested caution against suing another company that had hired an ex-employee of the patentee who knew the facts. The company and its officials pleaded nolo contendere. For the indictment, see United States v. Union Camp Corp., Crim. Action No. 4558 (E.D. Va. Nov. 30, 1967). For the complaint in the related civil action, alleging fraudulent procurement, see United States v. Union Camp Corp., Civ. No. 5005A, (E.D. Va. Nov. 4, 1968). The criminal case also involved a mandamus action in the Fourth Circuit. Union Camp Corp. v. Lewis, 385 F.2d 143 (4th Cir. 1967) (mandamus denied).

The facts concerning this case are summarized in a paper titled The Antitrust Consequences of Fraudulent Procurement and Enforcement of Patents, contained in 15 Antitrust Bull. 663 (1970) and in Patent Law Revision, Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Patents, Trademarks, and Copyrights of the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, 92d Cong., 1st Sess., Pursuant to S. Res. 32 on S. 643, S. 1253 and S. 1255, Part 2 and Appendix (May 13, 1971) at 506. - ↑ See id. at 507.

- ↑ 537 F.2d 187 (5th Cir. 1976).

- ↑ 537 F.2d at 188-89.

- ↑ 537 F.2d at 192-95.

- ↑ 537 F.2d at 197.

External links

- Text of Walker Process Equipment, Inc. v. Food Machinery & Chemical Corp., 382 U.S. 172 (1965) is available from: Justia Library of Congress Oyez (oral argument audio)