Naumkeag is a historical tribe of Eastern Algonquian-speaking Native American people who lived in northeastern Massachusetts. They controlled territory from the Charles River to the Merrimack River at the time of the Puritan migration to New England (1620–1640).

Naumkeag is also the term for a Native American settlement at the time of English colonization in present-day Salem, Massachusetts, meaning "fishing place," from namaas (fish), ki (place) and age (at)[1] or by another translation "eel-land."[2] However, the settlement Naumkeag was only one of a group of politically connected settlements in the early 1600s under the control of the sachem Nanepashemet and his wife the Squaw Sachem and their descendants. Although referred to in this article as Naumkeag, confusion exists about the proper contemporary endonym for this people, who are variously referred to in European documents as Naumkeag, Pawtucket, Penticut, Mystic, or Wamesit, or by the name of their current sachem or sagamore.[3]

Territory

Although the term Naumkeag refers to the pre-colonial settlement at present day Salem, the territory this polity controlled was much larger, as attested by the number of towns in Massachusetts that received deeds from Naumkeag sachems and their descendants, stretching from the northern border of the Charles River through the Mystic River watershed, up the coast as far as present day Peabody, then inland up to the southern border of the Merrimack River.

In 1639, the Squaw Sachem deeded large tracts of land to the young settlements of Newtowne (later Cambridge) and Charlestown,[4] an area encompassing the present day towns and cities of Cambridge, Newton, Lexington, Brighton, Arlington, Charlestown, Malden, Medford, Melrose, Everett, Woburn, Burlington, Winchester, Wilmington, Stoneham, Somerville, Reading, and Wakefield.

In the 1680s, James Quonopohit and his kin received payment for quitclaim deeds from Marblehead (1684), Lynn, Saugus, Swampscott, Lynnfield, Wakefield, North Reading, and Reading (1686), Salem (1687).[1]

History

Precontact

Although humans lived in the North American Eastern Woodlands for at least 15,000 years, the presence of a continental ice sheet extending south to the level of Long Island and Cape Cod have limited human habitation in present-day northeastern Massachusetts until the end of the last Ice Age, about 11,700 years ago. Paleoamerican remains in nearby Winthrop, Massachusetts and Merrimack, New Hampshire have been radiocarbon dated to 10,210±60 and 10,600 years ago, respectively.[5] Sea level rise due to the melting of continental ice sheets and disruption of soil layers from extensive development in the Boston area limit the earliest confirmed settlements within Naumkeag territory to the Woodland period beginning 2,000 years ago.[6]

The earliest historical records of the Naumkeag people are from European authors during the contact period from 1600 to 1630, supported by written reminiscences from Indigenous sources at the end of the 17th-century.

Nanepashemet

In 1614 English explorer John Smith explored the coast of New England, and included "Naemkeck" among the "countries" of the New England coast in an alliance with countries to the north under the bashabes (chief of chiefs) of the Penobscot, with a separate culture and government from the Massachusett to the south of the Charles River.[7] At this time the Naumkeag were under the leadership of Nanepashemet.[1]

At the time of the Great Migration to New England in the early 17th century, the Naumkeag population was already greatly depleted from disease and war. They engaged in a war with the Tarrantine (modern-day Mi'kmaq) people beginning in 1615.[8] A virgin soil epidemic due to an introduced European disease ravaged the populations of the Atlantic coast from 1616-1619 and took a particularly heavy toll with the Naumkeag people. The Tarrantines took advantage of this weakness, and further decimated their numbers, including killing their sachem, Nanepashemet, in 1619.[9]

Squaw Sachem of Mistick

In 1621, after establishing a settlement at Plymouth, a group of colonists including Edward Winslow and their native guide Tisquantum explored an area in present-day Medford, encountering the Naumkeag settlement where Nanepashemet had lived, several palisade fortifications for the 1615-1619 war between the Naumkeag and Tarrantine, and Nanepashemet's burial place.[10] Winslow attests to the area's control at that time by a "squaw sachem," an enemy of the Massachusett of Neponset,[10] who was the widow of Nanepashemet.

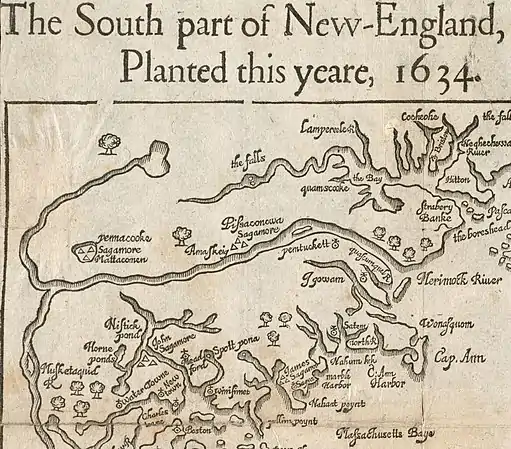

The general government of the tribe was continued by three of Nanepashemet's sons and his widow, only known in the historical record as the "Squaw Sachem of Mistick." She administered the region jointly with her three sons Wonohaquaham or "Sagamore John," Montowampate or "Sagamore James," and Wenepoykin or "Sagamore George." William Wood's map, dated 1634, but based on his travels in the area in the late 1620s, shows Sagamore John in present-day Medford and Sagamore James in present-day Lynn.[11] Wenepoykin or Sagamore George was sachem of the settlement of Naumkeag in present-day Salem by the time English settlers arrived in 1629, but he may have received assistance from an older family member until he came of age.[12][13] In 1633 there came another plague, probably smallpox, "which raged to such an extent as to nearly exterminate the tribe."[14] This epidemic killed both Montowampate and Wonohaquaham, leaving the Squaw Sachem and Wenepoykin in control of the area from modern day Chelsea to Lowell to Salem.

Wenepoykin

Although he survived the pandemic, after 1633, Wenepoykin or Sagamore George Rumney Marsh became known as "George No Nose" due to disfigurement from smallpox. When the Squaw Sachem died in roughly 1650, Wenepoykin became sole sachem of territory extending from present day Winthrop to Malden to North Reading to Lynn or even Salem, however his attempts to assert his claim to these lands through the settler's legal system were largely ineffective. During the next two decades, the size of the group further declined as the British Long Parliament and the Massachusetts General Court worked to relocate Native Americans into Praying Towns such as Natick, Massachusetts, drawing some converts from within Weyepoykin's family.

In 1675, Wenepoykin and some of the remaining Naumkeag joined Metacomet in King Philip's War, which was a stark turning point in the history of Native Americans in New England, and for the Naumkeag in particular. Wenepoykin was taken captive the next year in 1676 and sold into slavery in Barbados. During this same time, over 1000 nonbelligerent Praying Indians, some of them originally Naumkeag, were interned on Deer Island but only 167 survived to return to Praying Towns.

After 8 years of slavery in Barbados, Wenepoykin returned to Massachusetts in 1684 through the intercession of John Eliot, where he joined some remaining family members in Natick, but died later the same year, leaving his lands to a maternal kinsman James Quonopohit a.k.a. James Rumney Marsh, though by this time most of the hereditary territory of the sachem was occupied by English settlers.

Quonopohit

James Quonopohit or Rumney Marsh was a maternal kinsman of Wenepoykin living in the Natick praying town at the time the sachem entrusted him with title to Naumkeag lands in 1684.[1] By the time Quonopohit received this inheritance, there were many more European settlers living in Naumkeag territories than Naumkeag, many of whom had relocated to Natick as praying Indians, been killed in King Philip's War, fled north to join the burgeoning Wabenaki Confederacy, or been sold into slavery in Barbados.

However, in June of the same year, following the restoration of the English monarchy, the charter of the Massachusetts Bay Colony was revoked[15] in the formation of the Dominion of New England. This put a number of established New England settlements in a difficult position to justify their right to occupy land that had been granted under a now invalid charter, and created an opportunity for Quonopohit and his kin to seek payment for their traditional territory. They presented their claims to rightful ownership and were eventually paid for deeds to the present day towns of Marblehead (1684), Lynn, Saugus, Swampscott, Lynnfield, Wakefield, North Reading, and Reading (1686), Salem (1687).[1]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Perley, Sidney (1912). The Indian land titles of Essex County, Massachusetts. Salem: Essex Book and Print Club. pp. 8–12. Retrieved 2008-12-11.

- ↑ Douglas-Lithgow, R. A. (1909). Dictionary of American-Indian Place and Proper Names in New England. Salem, Massachusetts: Salem Press. p. 132.

- ↑ Lepionka, Mary Ellen (2018-03-28). "CHAPTER 1 What do our Algonquian place names really mean?". Native Americans of Cape Ann. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- ↑ "Medford Historical Society Papers, Volume 24., The Indians of the Mystic valley and the litigation over their land". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2021-12-12.

- ↑ Chandler, Jim (Fall 2001). "On the Shore of a Pleistocene Lake: the Wamsutta Site". Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society. 62 (2): 57–58.

- ↑ Massachusetts Historical Commission (1985). MHC Reconnaissance Survey Town Report: Salem (PDF).

- ↑ Smith, John (1616). A description of New England. Washington: P. Force. p. 5.

- ↑ Roads, Samuel (1880). History and Traditions of Marblehead. Boston: Houghton Osgood and Company. p. 2. Retrieved 2009-07-10.

- ↑ Roads, p. 2

- 1 2 Bradford, William; Winslow, Edward; Dexter, Henry Martyn (1865). Mourt's relation or journal of the plantation at Plymouth. Harvard University. Boston, J. K. Wiggin.

- 1 2 Wood, William (1634). "The south part of New England as it planted this yeare, 1634". www.digitalcommonwealth.org. Retrieved 2021-12-12.

- ↑ Lewis, Alonzo; Newhall, James R. (1865). The History of Lynn. John L. Shorey.

- ↑ "Wenepoykin". Menotomy Journal.

- ↑ Roads, p. 4

- ↑ Hall, Michael G. (1979). "Origins in Massachusetts of the Constitutional Doctrine of Advice and Consent". Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society. 91: 3–15. ISSN 0076-4981. JSTOR 25080845.