Washington Bookshop, also known as the Washington Cooperative Bookshop, was a World War II-era[1] bookstore in Washington, DC, at 916 17th St NW. It was established in 1938 as a cooperative.[2] Its 1200 members were able to purchase books from this bookshop at a special discounted rate;[2] there were also an art gallery and a lecture space where evening events were held. Lectures held at the store included a 12-week series of lectures on anthropology by Paul Radin; Eleanor Roosevelt also spoke to the bookshop's members. The store also had its own string quartet. Considered one of the best bookstores in Washington, it closed in 1950.[3]

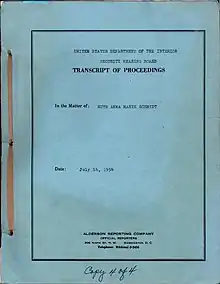

The bookstore was accused several times of being communist-leaning; however, it was not operated under the auspices of the Communist Party and did not profess to be, although the works of Marx, Engels and Lenin and publications like Soviet Russia Today were sold there. The store handled popular works as well as an extensive selection of books and periodicals on political topics; these latter were not limited to works by communist-approved authors. The store's customers, many of whom joined just to get the discount on new books, included prominent Washingtonians like Louis Brandeis. Other members, such as geologist Ruth A. M. Schmidt, joined the Bookshop because of its mission to work towards racial equality.[4]: 4 Members of the Washington Bookshop who were federal employees were investigated by federal loyalty boards, while others were blacklisted as communist suspects.[1] Lawrence Hill (1912–1988), a 1934 graduate of Yale and later one of the founders of Hill & Wang, was the bookstore manager until he left in 1942 to join the sales force at Knopf.

The chair of the bookstore's board, David Wahl, a Library of Congress employee (later with the Bureau of Economic Warfare and the OSS), was accused of being a Soviet spy, and a number of books have repeated this allegation. He was never formally charged, and the portions of his FBI file which have been made public are so heavily redacted that it is impossible to determine what the substance of the allegations was, although it is known that NSA code experts speculated that he was the Soviet agent who appears in the Venona intercepts under the codename "Pink." John Earl Haynes, Harvey Klehr and Alexander Vassilliev in their 2009 book Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America positively identify him as "Pink", a Soviet intelligence agent recruited in the 1930s, arguing that the details of Pink's resume fit Wahl and no one else.[5] Philip Keeney of the Library of Congress and Mrs. Nathan Gregory Silvermaster were among the other accused Soviet agents who had a connection with the bookshop.

On May 16, 1941, staffers of the Dies Committee with a subpoena raided the bookshop and seized its membership list of 1200 names out of the hands of a woman manager who was attempting to leave with it.[6] This list was used by the Dies Committee to produce a color coded chart showing the membership interlocks between the bookshop and other alleged communist front groups in Washington. The Civil Service Commission later ruled that membership in the bookshop was insufficient grounds for firing a government employee.[7]

References

- 1 2 Richard M. Fried (1990). Nightmare in Red: The McCarthy Era in Perspective. Oxford University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-19-987873-4. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- 1 2 Rosalee McReynolds; Louise S. Robbins (2009). The Librarian Spies: Philip and Mary Jane Keeney and Cold War Espionage. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-275-99448-8. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ↑ Goldstein, Robert Justin. "Watching the Books: Federal Suppression of the Washington Cooperative Bookshop 1939–1950", American Communist History, vol. 12, no. 3 (2013), p. 237-265.

- ↑ Transcripts of hearing October 25, 1950. (1950). Ruth A. M. Schmidt papers, 1912–2015. UAA/APU Consortium Library Archives and Special Collections, University of Alaska Anchorage. HMC-0792. Box 2, Folder 14.

- ↑ Haynes, John Earl, et al., Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America (Yale Univ. Press, 2009), p. 207-209.

- ↑ Folsom, Franklin. Days of Anger, Days of Hope: A Memoir of the League of American Writers 1937–1942 (Univ. Press of Colorado, 1994), p. 150.

- ↑ Caute, David. The Great Fear (Simon & Schuster), p. 268.