In the latter part of the nineteenth century, discoveries of gold at a number of locations in Western Australia caused large influxes of prospectors from overseas and interstate, and classic gold rushes.[2][3] Significant finds included:

- Halls Creek in 1885, found by Charles Hall and Jack Slattery. Triggered the "Kimberley gold rush".[4]

- Near Southern Cross in 1887, found by the party of Harry Francis Anstey. The "Yilgarn gold rush".[5][6]

- Cue in 1891, found by Michael Fitzgerald, Edward Heffernan and Tom Cue. The "Murchison gold rush".[7]

- Coolgardie in 1892, by Arthur Bailey and William Ford.

- Kalgoorlie in 1893, by Patrick "Paddy" Hannan, Tom Flanagan and Dan Shea.

A small rush at Nundamurrah Pool, on the Greenough River, near Mullewa, east of Geraldton occurred in August 1893.[8]

The Kalgoorlie event in particular, following the June 1893 discovery of alluvial gold at the base of Mount Charlotte by Irish prospectors Paddy Hannan, Tom Flanagan and Dan O'Shea, saw a massive population increase and ultimately, brought great wealth to the state. Capital works, including roads and railways and in 1896, construction of the ambitious Goldfields Water Supply Scheme, came about on the back of the gold rushes.

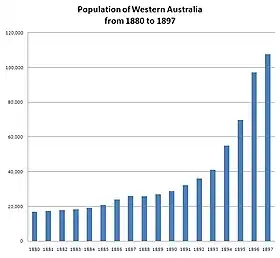

The population in Western Australia in 1891 was 49,782. By 1895 it had doubled to 100,515, and by 1901 was 184,124.[2]

The far-reaching nature of the mining excitement drew men from all over the world in 1895. People immigrated from Africa and America, Great Britain and Europe, China and India, New Zealand and the South Sea Islands, and from mining centres in Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, and South Australia. There was a total of 29,523 immigrants (24,173 males and 5,350 females) in 1895, while the emigration amounted to 11,129, leaving Western Australia the gainer by 18,394 persons. The population of the colony in 1895 was 101,235, made up of 69,727 males and 31,508 females. The immigration in December was greater than that of any preceding month, and totalled 4,540. Most of these people came from the Eastern colonies, which were still greatly depressed.

— W.B. Kimberly, ed. (1897). History of West Australia. p. 322.

These previously unexplored eastern districts were hot and barren and had limited natural water supplies or pre-existing infrastructure to support sudden influxes of people. As a result, all supplies had to be carted, either from Perth or Esperance. Carted water was sold for up to 5 shillings per gallon.

Kimberley

Prospector Charles Hall and others found alluvial gold in the eastern Kimberly region in 1885. The find created the first gold rush in Western Australia. In terms of gold yield, the rush was not particularly successful, but was the first significant find in the northern and western parts of Australia. It was nearly 40 years after the Victorian rushes.[9]

Yilgarn

The "Yilgarn gold rush" refers to a rush which commenced in 1888 after the November 1887 discovery of gold in the Yilgarn Hills area, north of Southern Cross.[10][11] Yilgarn is an Aboriginal word for white quartz, a common indicator of gold.

Murchison

Gold was discovered in 1892 though there is uncertainty as to who made the first find. Michael Fitzgerald and Edward Heffernan collected 260 ounces after being given a nugget by an Aboriginal known as 'Governor'. Tom Cue travelled to Nannine to register their claim. The townsite was gazetted in 1893 and named after Tom Cue. The town's first water supply was a well in the centre of the main street; after an outbreak of typhoid fever, the well was capped with a rotunda built over the top. The water supply was replaced by another well dug near Lake Nallan and carted 20 km south to the townsite. The town of Day Dawn, 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) south, was established within a year; by 1900 a hospital and cemetery were established between the two towns and they had three newspapers operating. The rivalry between the towns fuelled a diverse sporting culture in the area. Cycling and horse-racing groups held regular events attracting competitors from as far away as Perth and Kalgoorlie.

Coolgardie

Gold was discovered by Arthur Bailey in 1892. The Bailey's Reward gold mine would become one of the richest mines in the state.

Kalgoorlie

Prospectors Paddy Hannan, Tom Flanagan and Dan Shea found 100 ounces of alluvial gold at Mount Charlotte in 1894. After Hannan registered the reward claim, 750 men were prospecting in the area within three days. A town quickly sprang up which was initially called Hannans and later Kalgoorlie.

Whilst new prospectors were arriving in the colony, large numbers of workers were also moving between the various districts as new discoveries happened. False and exaggerated rumours were also rampant and many died from thirst and disease.

See also

References

- ↑ "Population by sex, states and territories, 31 December 1788 onwards". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2008.

- 1 2 Trinca, Mathew (1997). "The Goldrush". Launching the Ship of State: A Constitutional History of Western Australia. Centre for Western Australian History, University of Western Australia. Archived from the original on 9 September 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2004 – via The Constitutional Centre of Western Australia.

- ↑ "Gold Rush in the West". National Film and Sound Archive of Australia. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ↑ "OUR FIRST GOLD RUSH". Western Argus. Kalgoorlie, WA: National Library of Australia. 19 May 1931. p. 29. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ↑ "The Yilgarn Hills Gold-Fields", The West Australian (Perth) 16 November 1887, p.3

- ↑ "The Discovery of the Yilgarn Goldfields", Western Mail (Perth), 7 September 1889, p.4

- ↑ "THE MURCHISON GOLD DISCOVERY". Western Mail. Perth: National Library of Australia. 25 July 1891. p. 25. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ↑ "MINING NEWS". South Australian Register. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 22 August 1893. p. 5. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ↑ Playford, Phillip Elliot (22 December 2005). "The Kimberley gold rush of 1885–86" (pdf). 2004–2005 Annual Review. Perth, WA: Geological Survey of Western Australia: 33–37. ISSN 1324-504X.

- ↑ "Miscellaneous". Sunday Times. Perth: National Library of Australia. 5 April 1914. p. 15 Section: FIRST SECTION. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ↑ "THE YILGARN FIELD". The Barrier Miner. Broken Hill, NSW: National Library of Australia. 17 November 1892. p. 2. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

Further reading

- Franklin White. Miner with a Heart of Gold - Biography of a Mineral Science and Engineering Educator. FriesenPress. 2020. ISBN 978-1-5255-7765-9 (Hardcover) ISBN 978-1-5255-7766-6 (Paperback) ISBN 978-1-5255-7767-3 (eBook).