Whitewright, Texas | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Downtown Whitewright, Texas | |

| Motto: "Warm Hearts. Warm People. Winning Ways."[2] | |

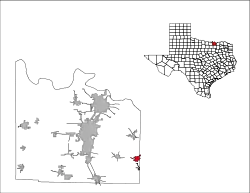

Location of Whitewright, Texas | |

| |

| Coordinates: 33°30′40″N 96°23′36″W / 33.51111°N 96.39333°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Texas |

| Counties | Grayson, Fannin |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1.86 sq mi (4.82 km2) |

| • Land | 1.86 sq mi (4.81 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.01 km2) |

| Elevation | 751 ft (229 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 1,604 |

| • Estimate (2019)[4] | 1,721 |

| • Density | 927.26/sq mi (357.94/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 75491 |

| Area code | 903 |

| FIPS code | 48-78628[5] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1371463[6] |

| Website | www |

Whitewright is a town[1] in Fannin and Grayson Counties in the U.S. state of Texas. The population was 1,604 at the 2010 census,[7] down from 1,740 at the 2000 census.

The Grayson County portion of Whitewright is part of the Sherman–Denison Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History

The settlement was established in 1878, when New York investor and financier William Whitewright Jr. (1815–1898), after whom the community was named, purchased a tract of land in the path of the Missouri–Kansas–Texas Railroad, which was then extending its tracks across the county from Sherman to Greenville. Whitewright had the land surveyed as a townsite and left two of his agents, Jim Reeves and Jim Batsell, to sell lots in the new community. Likely due to the combination of its rail connection and its location in the center of perhaps the richest farmland in the county near the headwaters of Bois d' Arc Creek, Whitewright soon attracted settlers and businesses.

Within 10 years of its founding, the community had incorporated and supported a private school, Grayson College, a public school, a newspaper, and several businesses, including three hotels, two cotton gins, and two banks. Jas. A. Batsell served as the first postmaster beginning on April 8, 1878. In 1885, Peter McKenna took over as postmaster, and the facility was officially commissioned as the Whitewright post office on December 7, 1888.

By 1900, the population of Whitewright was 1,804. Although the population declined slightly, to 1,563 in 1910 and 1,666 in 1920, the business community flourished. By the mid-1920s, both the Missouri-Kansas-Texas and the Cotton Belt served the town, and 68 businesses, including two banks and manufacturers of cottonseed oil and flour, operated locally. Whitewright served as a marketing, retail, and commercial center for the farmers of the surrounding area, who produced such crops as cotton, wheat, and corn.

The population rose from 1,480 in 1936 to 1,537 by the late 1940s. The number of businesses, however, declined from 60 to 46. During the 1970s and 1980s, seven factories, producing goods ranging from sausage to clothing to fertilizers, employed local workers. By 1989, Whitewright had 26 businesses, and in 1990, the population was 1,713. In 2000, the community had 1,740 inhabitants and 106 businesses.

1911 Fire

On June 12, 1911, a fire that started in a trash pile and was fanned by high winds destroyed most of the Whitewright business district. Along with the fire station and city hall, 43 business were destroyed and 75 residences were damaged, 27 of those destroyed. Units from the Denison and Sherman fire departments were called to assist, but the fire was reported under control before the Sherman department could get underway.[8]

Quedlinburg treasures

Whitewright was the home of US Lieutenant Joe Tom Meador, who after World War II looted several major pieces of art from a cave near Quedlinburg, Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. On April 19, 1945, American troops occupied Quedlinburg. Various treasures of art were secured in a cave near the castle Altenburg. Meador was responsible for the security of the cave. Meador, a soldier with good knowledge of art, recognized the importance of the treasures (among them being the Gospel of Samuel and the Crystals of Constantinople). He sent the treasures to Whitewright via army mail, and the art was placed in a safe at the First National Bank of Whitewright.

Meador died in 1980, and his heirs tried to sell 10 pieces of Beutekunst (looted art) on the international art market. After a long search and judicial processes, the art was returned to Germany in 1992 and were investigated because of damages to the pieces. At first, those stolen artifacts were exhibited in Munich and Berlin, but were finally returned to Quedlinburg in 1993. However, two of the pieces stolen by Meador are still in the United States at an unknown location.

Geography

Whitewright is located in eastern Grayson County at 33°30′40″N 96°23′36″W / 33.51111°N 96.39333°W (33.511136, –96.393400),[9] with a small portion extending east into Fannin County. U.S. Route 69 passes through the southern and western parts of the city, leading northwest 20 miles (32 km) to Denison and southeast 33 miles (53 km) to Greenville. Texas State Highway 11 crosses the southern part of Whitewright with US 69, leading southeast 36 miles (58 km) to Commerce and northwest 17 miles (27 km) to Sherman.

According to the United States Census Bureau, Whitewright has a total area of 1.9 square miles (4.8 km2), of which 0.004 square miles (0.01 km2), or 0.21%, is water.[7]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 100 | — | |

| 1890 | 880 | 780.0% | |

| 1900 | 1,804 | 105.0% | |

| 1910 | 1,563 | −13.4% | |

| 1920 | 1,666 | 6.6% | |

| 1930 | 1,480 | −11.2% | |

| 1940 | 1,537 | 3.9% | |

| 1950 | 1,372 | −10.7% | |

| 1960 | 1,315 | −4.2% | |

| 1970 | 1,745 | 32.7% | |

| 1980 | 1,760 | 0.9% | |

| 1990 | 1,713 | −2.7% | |

| 2000 | 1,740 | 1.6% | |

| 2010 | 1,604 | −7.8% | |

| 2020 | 1,725 | 7.5% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 1,721 | [4] | 7.3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[10] | |||

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 1,317 | 76.35% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 133 | 7.71% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 12 | 0.7% |

| Asian (NH) | 5 | 0.29% |

| Mixed/Multi-Racial (NH) | 94 | 5.45% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 164 | 9.51% |

| Total | 1,725 |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 1,725 people, 745 households, and 408 families residing in the town.

Education

The city is served by the Whitewright Independent School District and is home to the Whitewright Tigers.

Notable people

- Benny Binion, Las Vegas casino owner; convicted murderer

- John Wesley Hardin, Texas outlaw

- Julie Johnson, actress

- Kay Kimbell, benefactor of the Kimbell Art Museum

- Tyrone Swoopes, University of Texas athlete

- George Washington Truett, Southern Baptist clergyman

- Guy Wilkerson, actor

References

- 1 2 "Texas Cities and Towns Sorted by County". www.county.org. Retrieved December 26, 2016.

- ↑ City of Whitewright official website

- ↑ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- 1 2 "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ↑ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- 1 2 "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Whitewright town, Texas". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved August 23, 2016.

- ↑ Beitler, Stu. "Whitewright, TX Fire In Business District, June 1911". GenDisasters. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved May 22, 2022.

- ↑ https://www.census.gov/

- ↑ "About the Hispanic Population and its Origin". www.census.gov. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

Further reading

- Michael Fritz Johann, "Aus Texas zurückgekehrt: der spätgotische Buchdeckel aus dem Quedlinburger Schatz". In: Denkmalkunde und Denkmalpflege (1995), p. 275-282.

- Friedemann Goßlau: Verloren, gefunden, heimgeholt. Die Wiedervereinigung des Quedlinburger Domschatzes. Quedlinburg 1996.

- William H. Honan: Treasure Hunt. A New York Times Reporter Tracks the Quedlinburg Hoard. New York 1997.

- Siegfried Kogelfranz/Willi A. Korte: Quedlinburg – Texas und zurück. Schwarzhandel mit geraubter Kunst. Munich 1994.

- Emily Sano/David Kusin (Hg.): "The Quedlinburg Treasury". Dallas Museum of Art 1991.