| Who's Afraid of Aunt Jemima? | |

|---|---|

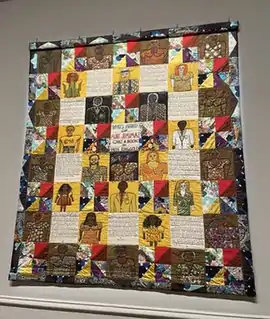

Who's Afraid of Aunt Jemima? at the National Gallery of Art in 2022 | |

| Artist | Faith Ringgold |

| Year | 1983 |

| Medium | Acrylic on canvas, quilt art |

| Movement | Black Arts Movement, Black feminism, Feminist art |

| Dimensions | 229 cm × 203 cm (90 in × 80 in) |

| Location | Glenstone, Potomac, Maryland[1] |

Who's Afraid of Aunt Jemima? is an acrylic on canvas narrative quilt made by American artist Faith Ringgold in 1983.[1] Named for the Edward Albee play Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and the character Aunt Jemima, the work is Ringgold's first story quilt and marks the early stages of the artist's shift from oil painting to quilting.[2][3]

Description

Who's Afraid of Aunt Jemima? is a quilt work made with acrylic paint and consists of 56 square panels, bordered by patterned fabric.[1] 28 panels contain paintings of people, 18 panels contain designs of patterned fabric, and 10 panels contain text, including the center panel which contains the title of the work.[2]

The text in the work tells the life story of a fictional Black woman from New Orleans named Jemima Blakey and her descendants and their families.[2] Ringgold based the story on the lives of her aunts and named the character after the blackface minstrel show character and longtime pancake syrup brand mascot Aunt Jemima.[4][2] The story of Jemima Blakey's life as a business owner, independent thinker, and strong matriarch is in distinct contrast to the Aunt Jemima character, "the most maligned Black female stereotype."[5] The text includes numerous references to the various figures painted in the work, 15 of which are labeled with letters and names to correspond with characters from the story.[1]

History

The work was first shown at Ringgold's solo exhibition at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 1984 and is the first of her extensive portfolio of story quilts, though not her first work of quilt art.[2] Ringgold has said she began making these narrative quilts with extensive text after being unable to find a publisher that would accept her autobiography. She began quilting so that "when my quilts were hung up to look at, or photographed for a book, people could still read my stories."[6]

The work was acquired by Glenstone in Potomac, Maryland.[7]

Reception

Critic Benjamin Genocchio described the work in The New York Times as "visually beautiful" and "filled with moments of wry or bitter comedy."[4] Writing in Tank about the work's showing in a 2019 exhibition at the Serpentine Galleries, Sarah Muttardi said the piece "[breaks] down the racist stereotype that [Black] women lacked drive or business acumen," and shows Ringgold's "disdain for the lack of positive images of Black women in contemporary media and art."[8] Writing in The New Yorker, critic Julian Lucas called the work "magnificent" and said it "elevates the figure of stereotype into the matriarch of a sprawling clan."[9]

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Faith Ringgold". Glenstone. Archived from the original on 20 April 2022. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Durón, Maximilíano (20 June 2019). "Artists Betye Saar, Faith Ringgold, and Renee Cox Called for Aunt Jemima's Liberation Years Ago". ARTnews. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ↑ Hemmings, Jessica (Summer 2020). "That's Not Your Story: Faith Ringgold Publishing on Cloth". Parse. University of Gothenburg. Archived from the original on 24 July 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- 1 2 Genocchio, Benjamin (22 May 2009). "Master of Story Quilts and Much More". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 June 2021. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ↑ Tucker, Marcia (1994). Bad Girls. New York: The MIT Press. p. 70. ISBN 9780262700535.

- ↑ ""Faith Ringgold: An American Artist" to Open February 2018". Crocker Art Museum. 22 December 2017. Archived from the original on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ↑ Crow, Kelly (31 March 2021). "At Age 90, Artist Faith Ringgold Is Still Speaking Her Mind". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 12 March 2022. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ↑ Muttardi, Sarah (July 2019). "REVIEW - Who's Afraid of Aunt Jemima?". Tank. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ↑ Lucas, Julian (4 May 2022). "A Visionary Show Moves Black History Beyond Borders". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on 4 May 2022. Retrieved 9 May 2022.