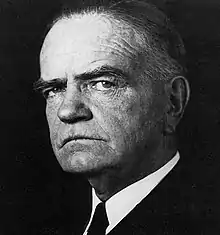

William Halsey Jr. | |

|---|---|

Fleet Admiral William Frederick Halsey Jr. c. 1945 | |

| Birth name | William Frederick Halsey Jr. |

| Nickname(s) |

|

| Born | October 30, 1882 Elizabeth, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Died | August 16, 1959 (aged 76) Fishers Island, New York, U.S. |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1904–1959[note 1] |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | |

William Frederick "Bull" Halsey Jr. (October 30, 1882 – August 16, 1959) was an American Navy admiral during World War II. He is one of four officers to have attained the rank of five-star fleet admiral of the United States Navy, the others being William Leahy, Ernest King, and Chester W. Nimitz.

Born in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Halsey graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1904. He served in the Great White Fleet and, during World War I, commanded the destroyer USS Shaw. He took command of the aircraft carrier USS Saratoga in 1935 after completing a course in naval aviation, and was promoted to the rank of rear admiral in 1938. At the start of the War in the Pacific (1941–1945), Halsey commanded the task force centered on the carrier USS Enterprise in a series of raids against Japanese-held targets.

Halsey was made commander of the South Pacific Area, and led the Allied forces over the course of the Battle for Guadalcanal (1942–1943) and the fighting up the Solomon chain (1942–1945).[2] In 1943 he was made commander of the Third Fleet, the post he held through the rest of the war.[3] He took part in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, the largest naval battle of the Second World War and, by some criteria, the largest naval battle in history. He was promoted to fleet admiral in December 1945 and retired from active service in March 1947.

Early years

Halsey was born in Elizabeth, New Jersey, on October 30, 1882, the son of Anna Masters (Brewster) and United States Navy Captain William F. Halsey

Halsey was of English ancestry. All of his ancestors came to America from England and all of them emigrated from England to New England in the early 1600s. He felt a "kinship" with his ancestors, including Captain John Halsey of colonial Massachusetts who served in the Royal Navy in Queen Anne's War from 1702 to 1713 where he raided French shipping.[4][5] Through his father he was a descendant of Senator Rufus King, who was an American lawyer, politician, diplomat, and Federalist. Halsey attended the Pingry School.[6]

After waiting two years to receive an appointment to the United States Naval Academy, Halsey decided to study medicine at the University of Virginia and then join the Navy as a physician. He chose Virginia because his best friend, Karl Osterhause, was there. While there, Halsey joined the Delta Psi fraternity and was also a member of the secretive Seven Society.[7] After his first year, Halsey received his appointment to the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis, and entered the academy in the fall of 1900. While attending the academy he lettered in football as a fullback and earned several athletic honors. Halsey graduated from the Naval Academy on February 2, 1904.[8]

Following graduation he spent his early service years in battleships, and sailed with the main battle fleet aboard the battleship USS Kansas as Roosevelt's Great White Fleet circumnavigated the globe from 1907 to 1909. Halsey was on the bridge of the battleship USS Missouri on Wednesday, April 13, 1904, when a flareback from the port gun in her aft turret ignited a powder charge and set off two others. No explosion occurred, but the rapid burning of the powder burnt and suffocated to death 31 officers and enlisted sailors. This resulted in Halsey dreading the 13th of every month, especially when it fell on a Wednesday.[9]

After his service on Missouri, Halsey served aboard torpedo boats, beginning with USS Du Pont in 1909. Halsey was one of the few officers who was promoted directly from ensign to full lieutenant, skipping the rank of lieutenant (junior grade).[10] Torpedoes and torpedo boats became specialties of his, and he commanded the First Group of the Atlantic Fleet's Torpedo Flotilla in 1912 through 1913. Halsey commanded a number of torpedo boats and destroyers during the 1910s and 1920s. At that time, the destroyer and the torpedo boat, through extremely hazardous delivery methods, were the most effective way to bring the torpedo into combat against capital ships. Then-Lieutenant Commander Halsey's World War I service, including command of USS Shaw in 1918, earned him the Navy Cross.

Interwar years

In October 1922, he was the Naval Attaché at the American Embassy in Berlin, Germany. One year later, he was given additional duty as naval attaché at the American Embassies in Christiania, Norway; Copenhagen, Denmark; and Stockholm, Sweden. He then returned to sea duty, again in destroyers in European waters, in command of USS Dale and USS Osborne. Upon his return to the U.S. in 1927, he served one year as executive officer of the battleship USS Wyoming, and then for three years in command of USS Reina Mercedes, the station ship at the Naval Academy. Then-Captain Halsey continued his destroyer duty on his next two-year stint at sea, starting in 1930 as the Commander of Destroyer Division Three of the Scouting Force, before returning to study at the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island.[11]

In 1934, the chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, Navy Rear Admiral Ernest King, offered Halsey command of the aircraft carrier USS Saratoga, subject to completion of the course of an air observer. Halsey elected to enroll as a cadet for the full 12-week Naval Aviator course rather than the simpler Naval Aviation Observer program. "I thought it better to be able to fly the aircraft itself than to just sit back and be at the mercy of the pilot," said Halsey at the time. Halsey earned his Naval Aviator's Wings on May 15, 1935, at the age of 52, the oldest person to do so in the history of the U.S. Navy. While he had approval from his wife to train as an observer, she learned from a letter after the fact that he had changed to pilot training, and she told her daughter, "What do you think the old fool is doing now? He's learning to fly!"[12] He went on to command the USS Saratoga, and later the Naval Air Station Pensacola at Pensacola, Florida. Halsey considered airpower an important part of the future navy, commenting, "The naval officer in the next war had better know his aviation, and good." Halsey was promoted to rear admiral in 1938. During this time he commanded carrier divisions and served as the overall commander of the Aircraft Battle Force.

World War II

Traditional naval doctrine envisioned naval combat fought between opposing battleship gun lines. This view was challenged when Army Air Corps General Billy Mitchell demonstrated the capability of aircraft to substantially damage and sink even the most heavily armored naval vessel. In the interwar debate that followed, some saw the carrier as defensive in nature, providing air cover to protect the battle group from shore-based aircraft. Carrier-based aircraft were lighter in design and had not been shown to be as lethal. The adage "Capital ships cannot withstand land-based air power" was well known.[13] Aviation proponents, however, imagined bringing the fight to the enemy with the use of air power.[14] Halsey was a firm believer in the aircraft carrier as the primary naval offensive weapon system. When he testified at Admiral Husband Kimmel's hearing after the Pearl Harbor debacle he summed up American carrier tactics being to "get to the other fellow with everything you have as fast as you can and to dump it on him." Halsey testified he would never hesitate to use the carrier as an offensive weapon.

In April 1940, Halsey's ships, as part of Battle Fleet, moved to Hawaii and in June 1940, he was promoted to vice admiral (temporary rank), and was appointed commander Carrier Division 2 and commander Aircraft Battle Force.[15]

With tensions high and war imminent, U.S. Naval intelligence indicated Wake Island would be the target of a Japanese surprise attack. In response, on 28 November 1941 Admiral Kimmel ordered Halsey to take USS Enterprise to ferry aircraft to Wake Island to reinforce the Marines there. Kimmel had given Halsey "a free hand" to attack and destroy any Japanese military forces encountered.[15] The planes flew off her deck on December 2. Highly anxious of being spotted and then jumped by the Japanese carrier force, Halsey gave orders to "sink any shipping sighted, shoot down any plane encountered." His operations officer protested, "Goddammit, Admiral, you can't start a private war of your own! Who's going to take the responsibility?" Halsey replied, "I'll take it! If anything gets in my way, we'll shoot first and argue afterwards."[16]

A storm delayed Enterprise on her return voyage to Hawaii. Instead of returning on December 6 as planned, she was still 200 miles (320 km) out at sea, when she received word that the surprise attack anticipated was not at Wake Island, but at Pearl Harbor itself. News of the attack came in the form of overhearing desperate radio transmissions from one of her aircraft sent forward to Pearl Harbor, attempting to identify itself as American.[17] The plane was shot down, and her pilot and crew were lost. In the immediate wake of the attack upon Pearl Harbor, Admiral Kimmel named Halsey "commander of all the ships at sea."[15] Enterprise searched south and west of the Hawaiian islands for the Japanese attackers, but did not locate the six Japanese fleet carriers then retiring to the north and west.

Early Pacific carrier raids

_and_USS_Saratoga_(CV-3)_on_19_December_1942.jpg.webp)

Halsey and Enterprise slipped back into Pearl Harbor on the evening of December 8. Surveying the wreckage of the Pacific Fleet, he remarked, "Before we're through with them, the Japanese language will be spoken only in hell."[18] Halsey was an aggressive commander. Above all else, he was an energetic and demanding leader who had the ability to invigorate the U.S. Navy's fighting spirit when most required.[19] In the early months of the war, as the nation was rocked by the fall of one western bastion after another, Halsey looked to take the fight to the enemy. Serving as commander, Carrier Division 2, aboard his flagship Enterprise, Halsey led a series of hit-and-run raids against the Japanese, striking the Gilbert and Marshall islands in February, Wake Island in March, and carrying out the Doolittle Raid in April 1942 against the Japanese capital Tokyo and other places on Japan's largest and most populous island Honshu, the first air raid to strike the Japanese Home Islands, providing an important boost to American morale. Halsey's slogan, "Hit hard, hit fast, hit often," soon became a byword for the Navy.

Halsey returned to Pearl Harbor from his last raid on May 26, 1942, in poor health due to the extremely serious and stressful conditions at hand. He had spent nearly all of the previous six months on the bridge of the carrier Enterprise, directing the Navy's counterstrikes. Psoriasis covered a great deal of his body and caused unbearable itching, making it nearly impossible for him to sleep. Gaunt and having lost 20 pounds (9.1 kg), he was medically ordered to the hospital in Hawaii and was successfully treated.

Meanwhile, U.S. Naval intelligence had strongly ascertained that the Japanese were planning an attack on the central Pacific island of Midway. Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet, determined to take the opportunity to engage them. Losing Midway would have been a very serious threat because the Japanese then could easily take Hawaii and threaten the west coast of the United States. The loss of his most aggressive and combat experienced carrier admiral, Halsey, on the eve of this crisis was a severe blow to Nimitz.[20] Nimitz met with Halsey, who recommended his cruiser division commander, Rear Admiral Raymond Spruance, to take command for the upcoming Midway operation.[21] Nimitz considered the move, but it would mean stepping over Rear Admiral Frank Fletcher of Task Force 17, who was the senior of the two men. After interviewing Fletcher and reviewing his reports from the Coral Sea engagement, Nimitz was convinced that Fletcher's performance was sound, and he was given the responsibility of command in the defense of Midway.[22] Acting upon Halsey's recommendations, Nimitz then made Rear Admiral Spruance commander of Halsey's Task Force 16, comprising the carriers Enterprise and Hornet. To aid Spruance, who had no experience as the commander of a carrier force, Halsey sent along his irascible chief of staff, Captain Miles Browning.

Halsey's skin condition was so serious that he was sent on the light cruiser USS Detroit to San Francisco, where he was met by a leading allergist for specialized treatment. The skin condition soon receded but Halsey was ordered to stand down for the next six weeks and relax. While detached stateside during his convalescence, he visited family and traveled to Washington D.C. In late August, he accepted a speaking engagement at the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis. Prior to the discussion of his raids against the Japanese positions in the Marshall Islands, Halsey informed the midshipmen before him, "Missing the Battle of Midway has been the greatest disappointment of my career, but I am going back to the Pacific where I intend personally to have a crack at those yellow-bellied sons of bitches and their carriers," which was received with loud applause.[23]

At the completion of his convalescence in September 1942, Admiral Nimitz reassigned Halsey to Commander, Air Force, Pacific Fleet.

Commander, South Pacific Area

After being medically approved to return to duty, Halsey was named to command a carrier task force in the South Pacific Area. Since Enterprise was still laid up in Pearl Harbor undergoing repairs following the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, and the other ships of Task Force 16 were still being readied, he began a familiarization trip to the south Pacific on October 15, 1942, arriving at area headquarters at Nouméa in New Caledonia on October 18. The Guadalcanal campaign was at a critical juncture, with the 1st Marine Division, 11,000 men, under the command of Marine Major General Alexander Vandegrift holding on by a thread around Henderson Field. The Marines did receive additional support from the U.S. Army's 164th Infantry Regiment with a complement of 2,800 soldiers on October 13. This addition only helped to fill some of the serious holes and was insufficient to sustain the battle of itself.

During this critical juncture, naval support was tenuous due to Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley's reticence, malaise and lackluster performance.[15] Pacific Fleet commander Chester Nimitz had concluded that Ghormley had become dispirited and exhausted.[24][25][26] Nimitz made his decision to change the South Pacific Area commander while Halsey was en route. As Halsey's aircraft came to rest in Nouméa, a whaleboat came alongside carrying Ghormley's flag lieutenant. Meeting him before he could board the flagship, the lieutenant handed over a sealed envelope containing a message from Nimitz: "You will take command of the South Pacific Area and South Pacific forces immediately."[2]

The order came as an awkward surprise to Halsey. Ghormley was a long time personal friend, and had been since their days as teammates on the football team back at Annapolis. Awkward or not, the two men carried out their directives. Halsey's command now included all ground, sea, and air forces in the South Pacific area. News of the change flashed and produced an immediate boost to morale with the beleaguered Marines, energizing his command. He was widely considered the U.S. Navy's most aggressive admiral, and with good reason. He set about assessing the situation to determine what actions were needed. Ghormley had been unsure of his command's ability to maintain the Marine toehold on Guadalcanal, and had been mindful of leaving them trapped there for a repeat of the Bataan Peninsula disaster. Halsey punctiliously made it clear he did not plan to withdraw the Marines. He not only intended to counter the Japanese efforts to dislodge them, he intended to secure the island. Above all else, he wanted to regain the initiative and take the fight to the Japanese. It was two days after Halsey had taken command in October 1942 that he gave an order that all naval officers in the South Pacific would dispense with wearing neckties with their tropical uniforms. As Richard Frank commented in his account of the Battle for Guadalcanal:

Halsey said he gave this order to conform to Army practice and for comfort. To his command it viscerally evoked the image of a brawler stripping for action and symbolized a casting off of effete elegance no more appropriate to the tropics than to war.[27]

Halsey led the South Pacific command through what was for the U.S. Navy the most tenuous phase of the war. Halsey committed his limited naval forces through a series of naval battles around Guadalcanal, including the carrier engagements of the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands and the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal. These engagements checked the Japanese advance and drained their naval forces of carrier aircraft and pilots.

For his conduct, "can-do" leadership style, and increasing number of forces under his command, Halsey was promoted to four-star admiral in October 1942. The promotion put Halsey into sustained public spotlight for the first time, appearing on the cover of Time magazine's November 1942 issue[28] which quoted Halsey from his superior Nimitz as "professionally competent and militarily aggressive without being recklessly foolhardy" and that his promotion by the President was something "he richly deserves". Halsey's four-star insignia were welded together from two-star rear admiral insignia, which promptly replaced his vice admiral's stars which he sent to the relatives of those who contributed greatly to the campaign.[29][30]

In November, Halsey's willingness to place at risk his command's two fast battleships in the confined waters around Guadalcanal for a night engagement paid off with the U.S. Navy winning the battle, the decisive naval engagement of the Guadalcanal campaign that doomed the Japanese garrison and wrested control from the Japanese.

Japanese naval aviation proved to be formidable during the Solomon campaign.[31] In April 1943, Halsey assigned Rear Admiral Marc Mitscher to become Commander Air, Solomon Islands, where he directed a mixed bag of army, navy, marine and New Zealand aircraft in the airwar over Guadalcanal and up the Solomons chain. Said Halsey: "I knew we'd probably catch hell from the Japs in the air. That's why I sent Pete Mitscher up there. Pete was a fighting fool and I knew it."[32]

Typical for the period was an exchange that occurred between Halsey and one of his staff officers in June 1943. The South Pacific Area was expecting the arrival of an additional air group to support their next offensive. As a part of the long view of winning the war taken by Nimitz, upon its arrival at Fiji the group was given new orders to return stateside and be broken up, its pilots to be used as instructors for pilot training. Halsey's headquarters had been counting on the air group for their operations up the Solomons chain. The staff officer who brought the dispatch to Halsey remarked "If they do that to us we will have to go on the defensive." The admiral turned to the speaker and replied: "As long as I have one plane and one pilot, I will stay on the offensive."[33]

Halsey's forces spent the rest of the year battling up the Solomon Islands chain to Bougainville. At Bougainville the Japanese had two airfields in the southern tip of the island, and another at the northernmost peninsula, with a fourth on Buki just across the northern passage. Here, instead of landing near the Japanese airfields and taking them away against the bulk of the Japanese defenders, Halsey landed his invasion force of 14,000 Marines in Empress Augusta Bay, about halfway up the west coast of Bougainville. There he had the Seabees clear and build their own airfield. Two days after the landing, a large cruiser force was sent down from Japan to Rabaul in preparation for a night engagement against Halsey's screening force and supply ships in Empress Augusta Bay. The Japanese had been conserving their naval forces over the past year, but now committed a force of seven heavy cruisers, along with one light cruiser and four destroyers. At Rabaul the force refueled in preparation for the coming night battle. Halsey had no surface forces anywhere near equivalent strength to oppose them. Battleships Washington, South Dakota, and assorted cruisers had been transferred to the Central Pacific to support the upcoming invasion of Tarawa. Other than the destroyer screen, the only force Halsey had available were the carrier air groups on Saratoga and Princeton.

Rabaul was a heavily fortified port, with five airfields and extensive anti-aircraft batteries. Other than the surprise raid at Pearl Harbor, no mission against such a target had ever been accomplished with carrier aircraft. It was highly dangerous to the aircrews, and to the carriers as well. With the landing in the balance, Halsey sent his two carriers to steam north through the night to get into range of Rabaul, then launch a daybreak raid on the base. Aircraft from recently captured Vella Lavella were sent over to provide a combat air patrol over the carriers. All available aircraft from the two carriers were committed to the raid itself. The mission was a stunning success, so damaging the cruiser force at Rabaul as to make them no longer a threat. Aircraft losses in the raid were light. Halsey later described the threat to the landings as "the most desperate emergency that confronted me in my entire term as ComSoPac."[34]

Following the successful Bougainville operation, he then isolated and neutralized the Japanese naval stronghold at Rabaul by capturing surrounding positions in the Bismarck Archipelago in a series of amphibious landings known as Operation Cartwheel. This enabled the continuation of the drive north without the heavy fighting that would have been necessary to capture the base itself. With the neutralization of Rabaul, major operations in the South Pacific Area came to a close. With his determination and grit, Halsey had bolstered his command's resolve and seized the initiative from the Japanese until ships, aircraft and crews produced and trained in the States could arrive in 1943 and 1944 to tip the scales of the war in favor of the allies.[35]

Battles of the Central Pacific

%252C_December_1944.jpg.webp)

As the war progressed it moved out of the South Pacific and into the Central Pacific. Halsey's command shifted with it, and in May 1944 he was promoted to commanding officer of the newly formed Third Fleet. He commanded actions from the Philippines to Japan. From September 1944 to January 1945, he led the campaigns to take the Palaus, Leyte and Luzon, and on many raids on Japanese bases, including off the shores of Formosa, China, and Vietnam.

By this point in the conflict the U.S. Navy was doing things the Japanese high command had not thought possible. The Fast Carrier Task Force was able to bring to battle enough air power to overpower land based aircraft and dominate whatever area the fleet was operating in. Moreover, the Navy's ability to establish forward operating ports as they did at Majuro, Enewetak and Ulithi, and their ability to convoy supplies out to the combat task forces, allowed the fleet to operate for extended periods of time far out to sea in the central and western Pacific. The Japanese Navy conserved itself in port and would sortie in force to engage the enemy. The U.S. Navy remained at sea and on station, dominating whatever region it entered. The size of the Pacific Ocean, which Japanese planners had thought would limit the U.S. Navy's ability to operate in the western Pacific, would not be adequate to protect Japan.

Command of the "big blue fleet" was alternated with Raymond Spruance.[note 2] Under Spruance the fleet designation was the Fifth Fleet and the Fast Carrier Task Force was designated "Task Force 58". Under Halsey the fleet was designated Third Fleet and the Fast Carrier Task Force was designated "Task Force 38".[3] The split command structure was intended to confuse the Japanese and created a higher tempo of operations. While Spruance was at sea operating the fleet, Halsey and his staff, self-dubbed the "Department of Dirty Tricks", would be planning the next series of operations.[36] The two admirals were a contrast in styles. Halsey was aggressive and a risk taker. Spruance was calculating, professional, and cautious. Most higher-ranking officers preferred to serve under Spruance; most common sailors were proud to serve under Halsey.[37]

Leyte Gulf

In October 1944, amphibious forces of the U.S. Seventh Fleet carried out General Douglas MacArthur's major landings on the island of Leyte in the Central Philippines. Halsey's Third Fleet was assigned to cover and support Seventh Fleet operations around Leyte. Halsey's plans assumed the Japanese fleet or a major portion of it would challenge the effort, creating an opportunity to engage it decisively. Halsey directed the Third Fleet "will seek the enemy and attempt to bring about a decisive engagement if he undertakes operations beyond support of superior land based air forces."[38]

In response to the invasion, the Japanese launched their final major naval effort, an operation known as 'Sho-Go', involving almost all their surviving fleet. It was aimed at destroying the invasion shipping in Leyte Gulf. The Northern Force of Admiral Jisaburō Ozawa was built around the remaining Japanese aircraft carriers, now weakened by the heavy loss of trained pilots. The Northern Force was meant to lure the covering U.S. forces away from the Gulf while two surface battle-groups, the Center Force and the Southern Force, were to break through to the beachhead and attack the invasion shipping. These forces were built around the remaining strength of the Japanese Navy, and comprised a total of 7 battleships and 16 cruisers. The operation brought about the Battle for Leyte Gulf, the largest naval battle of the Second World War and, by some criteria, the largest naval battle in history.

The Center Force commanded by Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita was located October 23 coming through the Palawan Passage by two American submarines, which attacked the force, sinking two heavy cruisers and damaging a third. The following day Third Fleet's aircraft carriers launched strikes against Kurita's Center Force, sinking the battleship Musashi and damaging the heavy cruiser Myōkō, causing the force to turn westward back towards its base. Kurita appeared to be retiring but he later reversed course and headed back into the San Bernardino Strait. At this point Ozawa's Northern Force was located by Third Fleet scout aircraft. Halsey made the momentous decision to take all available strength northwards to destroy the Japanese carrier forces, planning to strike them at dawn of October 25. He considered leaving a battle group behind to guard the strait, and made tentative plans to do so, but he felt he would also have to leave one of his three carrier groups to provide air cover, weakening his chance to crush the remaining Japanese carrier forces. The entire Third Fleet steamed northward. San Bernardino Strait was effectively left unguarded by any major surface fleet.

Battle off Samar

In moving Third Fleet northwards, Halsey failed to advise Admiral Thomas Kinkaid of Seventh Fleet of his decision. Seventh Fleet intercepts of organizational messages from Halsey to his own task group commanders seemed to indicate that Halsey had formed a task force and detached it to protect the San Bernardino Strait, but this was not the case. Kinkaid and his staff failed to confirm this with Halsey, and neither had confirmed this with Nimitz.

Despite aerial reconnaissance reports on the night of October 24–25 of Kurita's Center Force in the San Bernardino Strait, Halsey continued to take Third Fleet northwards, away from Leyte Gulf.

When Kurita's Center Force emerged from the San Bernardino Strait on the morning of October 25, there was nothing to oppose them except a small force of escort carriers and screening destroyers and destroyer escorts, Task Unit 77.4.3 "Taffy 3", which had been tasked and armed to attack troops on land and guard against submarines, not oppose the largest enemy surface fleet since the battle of Midway, led by the largest battleship in the world. Advancing down the coast of the island of Samar towards the troop transports and support ships of the Leyte Gulf landing, they took Seventh Fleet's escort carriers and their screening ships entirely by surprise.

In the desperate Battle off Samar which followed, Kurita's ships destroyed one of the escort carriers and three ships of the carriers' screen, and damaged a number of other ships as well. The remarkable resistance of the screening ships of Taffy 3 against Kurita's battle-group remains one of the most heroic feats in the history of the U.S. Navy. Their efforts and those of the several hundred aircraft that the escort carriers could put up, many of whom, however could not be armed with the most effective ordnance to deal with heavy surface ships in time, took a heavy toll on Kurita's ships and convinced him that he was facing a stronger force than was the case. Mistaking the escort carriers for Halsey's fleet carriers, and fearing entrapment from the six battleships of the Third Fleet battleship group, he decided to withdraw back through the San Bernardino Strait and to the west without achieving his objective of disrupting the Leyte landing.

When the Seventh Fleet's escort carriers found themselves under attack from the Center Force, Halsey began to receive a succession of desperate calls from Kinkaid asking for immediate assistance off Samar. For over two hours Halsey turned a deaf ear to these calls. Then, shortly after 10:00 hours,[39] a message was received from Admiral Nimitz: "Where is repeat where is Task Force 34? The world wonders". The tail end of this message, The world wonders, was intended as padding designed to confuse enemy decoders, but was mistakenly left in the message when it was handed to Halsey. The urgent inquiry had seemingly become a stinging rebuke. The fiery Halsey threw his hat on the deck of the bridge and began cursing.[39] Finally Halsey's Chief of Staff, Rear Admiral Robert "Mick" Carney, confronted him, telling Halsey "Stop it! What the hell's the matter with you? Pull yourself together."[16]

Halsey cooled but continued to steam Third Fleet northward to close on Ozawa's Northern Force for a full hour after receiving the signal from Nimitz.[39] Then, Halsey ordered Task Force 34 south. As Task Force 34 proceeded south they were further delayed when the battle force had to slow to 12 knots so that the battleships could refuel their escorting destroyers. The refueling cost a two and a half-hour further delay.[39] By the time Task Force 34 arrived at the scene it was too late to assist the Seventh Fleet's escort carrier groups. Kurita had already decided to retire and had left the area. A single straggling destroyer was caught by Halsey's advance cruisers and destroyers, but the rest of Kurita's force was able to escape.

Meanwhile, the major part of Third Fleet continued to close on Ozawa's Northern Force, which included one fleet carrier (the last surviving Japanese carrier of the six that had attacked Pearl Harbor) and three light carriers. The Battle off Cape Engaño resulted in Halsey's Third Fleet sinking all four of Ozawa's carriers.

The same attributes that made Halsey an invaluable leader in the desperate early months of the war, his desire to bring the fight to the enemy, his willingness to take on a gamble, worked against him in the later stages of the war. Halsey received much criticism for his decisions during the battle, with naval historian Samuel Morison terming the Third Fleet run to the north "Halsey's Blunder".[40] However, the destruction of the Japanese carriers had been an important goal up to that point, and the Leyte landings were still successful despite Halsey falling for the Japanese Navy's decoy.

Halsey's Typhoon

_during_Typhoon_Cobra%252C_December_1944.jpg.webp)

After the Leyte Gulf engagement, December found the Third Fleet confronted with another powerful enemy in the form of Typhoon Cobra, which was dubbed "Halsey's Typhoon" by many.

While conducting operations off the Philippines, the fleet had to discontinue refueling due to a Pacific storm. Rather than move Third Fleet away, Halsey chose to remain on station for another day. In fairness, he received conflicting information from Pearl Harbor and his own staff. The Hawaiian weathermen predicted a northerly path for the storm, which would have cleared Task Force 38 by some two hundred miles (320 km). Eventually his own staff provided a prediction regarding the direction of the storm that was far closer to the mark with a westerly direction.[41]

However, Halsey played the odds, declining to cancel planned operations and requiring the ships of Third Fleet to hold formation. On the evening of December 17 Third Fleet was unable to land its combat air patrol due to the pitching and rolling decks of the carriers. All the aircraft were ditched in the ocean and lost, but the pilots were all saved by accompanying destroyers. By 10:00 a.m. the next morning the barometer on the flagship was noted to be dropping precipitously. With increasingly heavy seas the fleet still attempted to maintain stations. The threat was greatest to the fleet's destroyers, which did not have the fuel reserves of the larger ships and were running dangerously low. Finally, at 11:49 am, Halsey issued the order for the ships of the fleet to take the most comfortable course available to them. Many of the smaller ships had already been forced to do so.

Between 11:00 a.m. and 2:00 pm, the typhoon did its worst damage, tossing the ships in 70-foot (21 m) waves. The barometer continued to drop and the wind roared at 83 knots (154 km/h) with gusts well over 100 knots (185 km/h). At 1:45 pm. Halsey issued a typhoon warning to Fleet Weather Central. By this time Third Fleet had lost three of its destroyers. By the time the storm had cleared the next day a great many ships in the fleet had been damaged, three destroyers were sunk, 146 aircraft were destroyed and 802 seamen had been lost. For the next three days Third Fleet conducted search and rescue operations, finally retiring to Ulithi on 22 December 1944.

Following the typhoon a Navy court of inquiry was convened on board USS Cascade in the Naval Base Ulithi. Admiral Nimitz, CINCPAC, was in attendance at the court, Vice Admiral John H. Hoover presided over the Court, with admirals George D. Murray and Glenn B. Davis as associate judges. Forty-three-year-old Captain Herbert K. Gates, of Cascade, was the Judge Advocate.[42] The inquiry found that though Halsey had committed an error of judgement in sailing the Third Fleet into the heart of the typhoon, it stopped short of unambiguously recommending sanction.[43] The events surrounding Typhoon Cobra were similar to those the Japanese navy had faced some nine years earlier in what they termed "The Fourth Fleet Incident."[44]

End of the war

During January 1945 the Third Fleet attacked Formosa and Luzon, and raided the South China Sea in support of the landing of U.S. Army forces on Luzon. At the conclusion of this operation, Halsey passed command of the ships that made up Third Fleet to Admiral Spruance on January 26, whereupon its designation changed to Fifth Fleet. Returning home Halsey was asked about General MacArthur, who was not the easiest man to work with, and vied with the Navy over the conduct and management of the war in the Pacific.[45] Halsey had worked well with MacArthur and did not mind saying so. When a reporter asked Halsey if he thought MacArthur's fleet (7th Fleet) would get to Tokyo first, the admiral grinned and answered "We're going there together." Then seriously he added "He's a very fine man. I have worked under him for over two years and have the greatest admiration and respect for him."[46]

Spruance held command of Fifth Fleet until May, when command returned to Halsey. In early June 1945 the Third Fleet again sailed through the path of a typhoon, Typhoon Connie. On this occasion, six men were swept overboard and lost, along with 75 airplanes lost or destroyed, with another 70 badly damaged. Though some ships sustained significant damage, none were lost. A Navy court of inquiry was again convened, this time recommending that Halsey be reassigned, but Admiral Nimitz declined to abide by this recommendation, citing Halsey's prior service record, despite that record including a previous instance of negligently sailing his fleet through a typhoon.[47]

Halsey led Third Fleet through the final stages of the war, striking targets on the Japanese homeland itself. Third Fleet aircraft conducted attacks upon Tokyo, the naval base at Kure and the northern Japanese island of Hokkaidō, and Third Fleet battleships engaged in the bombardment of a number of Japanese coastal cities in preparation for an invasion of Japan, which ultimately never had to be undertaken.

After the cessation of hostilities, Halsey, still aggressively cautious of Japanese kamikaze attacks, ordered Third Fleet to maintain a protective air cover with the following communiqué:

Cessation of hostilities.

War is over.

If any Japanese airplanes appear, shoot them down in a friendly way.[48]

He was present when Japan formally surrendered on the deck of his flagship, USS Missouri, on September 2, 1945.

Postwar years

Immediately after the surrender of Japan, 54 ships of the Third Fleet returned to the United States, with Halsey's four-star flag flying from USS South Dakota, for the annual Navy Day Celebrations in San Francisco on October 27, 1945. He hauled down his flag on November 22, 1945, and was assigned special duty in the Office of the Secretary of the Navy. On December 11, 1945, he took the oath as Fleet Admiral, becoming the fourth and still the most recent naval officer awarded that rank.[49] Halsey made a goodwill flying trip, passing by Central and South America, covering nearly 28,000 miles (45,000 km) and 11 nations. He retired from active service in March 1947, but as a Fleet Admiral, he was not taken off active duty status.

Halsey was asked about the weapons used to win the war and he answered:

If I had to give credit to the instruments and machines that won us the war in the Pacific, I would rate them in this order: submarines first, radar second, planes third, bulldozers fourth.[50]

Halsey joined the New Jersey Society of the Sons of the American Revolution in 1946. Upon retirement, he joined the board of two subsidiaries of the International Telephone and Telegraph Company, including the American Cable and Radio Corporation, and served until 1957. He maintained an office near the top of the ITT Building at 67 Broad Street, New York City in the late 1950s. He was involved in a number of efforts to preserve his former flagship USS Enterprise as a memorial in New York Harbor. They proved fruitless, as it was not possible to secure sufficient funding to preserve the ship.

Personal life

While at the University of Virginia he met Frances Cooke Grandy (1887–1968) of Norfolk, Virginia, whom Halsey called "Fan." After his return from the Great White Fleet's circumnavigation of the globe and upon his promotion to the rank of full lieutenant he was able to persuade her to marry him.[51] They married on December 1, 1909, at Christ Church in Norfolk. Among the ushers were Halsey's friends Thomas C. Hart and Husband E. Kimmel. Fan developed manic depression in the late 1930s and eventually had to live apart from Halsey.[52] The couple had two children, Margaret Bradford (October 10, 1910 – December 15, 1979) and William Frederick Halsey III (September 8, 1915 – September 23, 2003).[53][54] Halsey is also the great-uncle of actor Charles Oliver Hand, known professionally as Brett Halsey, who chose his stage name as a reference to him.[55]

Death

.jpg.webp)

While vacationing on Fishers Island, New York, Halsey died of a heart attack at age 76 on August 16, 1959.[11][56][57] After lying in state in the Washington National Cathedral, he was interred on August 20, near his parents in Arlington National Cemetery.[58] His wife, Frances Grandy Halsey, is buried with him.

Asked about his contribution in the Pacific and the role he played in defending the United States, Halsey said merely:

There are no great men, just great challenges which ordinary men, out of necessity, are forced by circumstances to meet.[59]

Dates of rank

United States Naval Academy Midshipman—Class of 1904

United States Naval Academy Midshipman—Class of 1904

| Ensign | Lieutenant, junior grade | Lieutenant | Lieutenant commander | Commander | Captain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-1 | O-2 | O-3 | O-4 | O-5 | O-6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| February 2, 1906 | February 2, 1909 | February 2, 1909 | August 29, 1916 | February 1, 1918 | February 10, 1927 |

| Commodore | Rear admiral | Vice admiral | Admiral | Fleet admiral |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-7 | O-8 | O-9 | O-10 | Special Grade |

|

|

|

|

|

| Never held | March 1, 1938 | June 13, 1940 | November 18, 1942 | December 11, 1945 |

Halsey never held the rank of lieutenant (junior grade), as he was appointed a full lieutenant after three years of service as an ensign. For administrative reasons, Halsey's naval record states he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant (junior grade) and lieutenant on the same day.[15]

At the time of Halsey's promotion to rear admiral, both rear admirals lower half (O-7) and rear admirals upper half (O-8) wore two stars. This was the case until 1942. During World War II and up until 1950, the Navy used the one star commodore rank for certain staff specialties.

Awards and decorations

| Naval Aviator insignia | |

| Navy Cross | |

| Navy Distinguished Service Medal with three gold stars in lieu of fourth award | |

| Army Distinguished Service Medal | |

| Presidential Unit Citation with bronze star in lieu of second award | |

| Mexican Service Medal | |

| World War I Victory Medal with Destroyer clasp | |

| American Defense Service Medal with Fleet clasp | |

| American Campaign Medal | |

| Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with twelve battle stars | |

| World War II Victory Medal | |

| National Defense Service Medal |

Foreign awards

| Argentina – Order of May of Naval Merit, Grand Cross (March 1, 1947) | |

| Brazil – Order of the Southern Cross, Grand Cross | |

| Chile – Grand Cross of Order of Merit of Chile | |

| Colombia – Grand Cross of Boyaca | |

| Panama – Orden Vasco Núñez de Balboa, Grand Cross | |

| Guatemala made him a Supreme Chief in the Order of the Quetzal. | |

| Ecuador – Order of Abdon Calderón, 1st Class | |

| United Kingdom – Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (KBE) | |

| Chile – Al Merito, First Class, Insignia and Diploma | |

| Cuba – Order of Naval Merit | |

| Greece – Order of the Redeemer | |

| Peru – Order of Ayacucho | |

| Venezuela – Order of the Liberator | |

| Philippines – Philippine Presidential Unit Citation | |

| Philippines – Philippine Liberation Medal with two stars |

Honors

- Halsey Field, NAS North Island in Coronado, California, dedicated October 20, 1960, celebrating 50 years of Naval Aviation (1911–1961).[61]

- Halsey Society, student Naval ROTC organization at Texas A&M University[62]

Buildings

- Admiral William F. Halsey Jr. Leadership Academy & William F. Halsey House, Elizabeth High School in Elizabeth, New Jersey[63]

- Halsey Field House, United States Naval Academy

- Halsey Gym, the main physical fitness center at Naval Air Facility Atsugi, Ayase, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan

- Halsey Hall, University of Virginia

- Halsey Terrace, U.S. Navy housing in Honolulu, Hawaii[64]

- Halsey Hall, Jonathan Dayton High School

- USS Halsey (BEQ-439), a Junior Enlisted Barracks for students going through initial training in Naval Station Great Lakes, Illinois

- W. F. Halsey Elementary School, RAF Edzell, Scotland, UK. DOD school closed in 1997 when the base closed.

Ships

- USS Halsey (CG-23), a Leahy-class guided-missile cruiser

- USS Halsey (DDG-97), an Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer

Streets

- Commodore Drive, Lynfield, New Zealand[65]

- William F. Halsey Avenue, Bakersfield, California

- Halsey Street, Chula Vista, California

- Halsey Boulevard, Foster City, California

- Halsey Street, San Leandro, California

- Halsey Avenue, Yuba City, California

- Halsey Street, East Hartford, Connecticut

- Halsey Road, Dover, Delaware

- Admiral Halsey Avenue, Daytona Beach, Florida[66]

- Halsey Roadd, Jacksonville, Florida

- Halsey Road, Milton, Florida

- Halsey Street, Pensacola, Florida

- Halsey Drive, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana

- Halsey Street, Colonel Bud Day Field, Sioux City, Iowa

- Halsey Street, Alexandria, Louisiana

- Halsey Road, Annapolis, Maryland

- Halsey Place, Baltimore, Maryland

- Halsey Street, Kensington, Maryland[67]

- Halsey Way, Natick, Massachusetts

- Admiral Halsey Road, Plymouth, Massachusetts

- Halsey Street, St. Louis, Missouri

- Admiral Halsey Drive, NE, Albuquerque, New Mexico

- Admiral Halsey Service Area, a north-bound rest area along the New Jersey Turnpike at mile marker 111 on Interstate 95, at the present New Jersey Route 81 interchange, in Elizabeth, New Jersey[68]

- Halsey Court, Princeton, New Jersey

- Halsey Street, Princeton, New Jersey

- Halsey Road, Toms River, New Jersey

- Halsey Street, Brooklyn, New York

- Halsey Drive, Riverside, Ohio

- Halsey Court, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

- Halsey Avenue, Middletown, Rhode Island

- Halsey Street, Newport, Rhode Island

- Halsey Drive, Warwick, Rhode Island

- Halsey Drive, Flower Mound, Texas

- Halsey Drive, Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Virginia

- South Halsey Drive, Whidbey Island, Washington

- Halsey Street, Eau Claire, Wisconsin

- Admiral Halsey Slope (Côte Amiral Halsey), Nouméa, New Caledonia

- Halsey Drive, Lynfield, New Zealand (Halsey visited New Zealand in 1908, however the drive may be named for British Admiral Lionel Halsey)[69]

In popular culture

- Halsey was portrayed by James Cagney in the 1959 bio-pic, The Gallant Hours; by James Whitmore in the 1970 film, Tora! Tora! Tora!; by Robert Mitchum in the 1976 film, Midway, and by Dennis Quaid in the 2019 film Midway.

- Halsey makes a brief appearance in Herman Wouk's novel The Winds of War, and has a more substantial supporting role in the sequel War and Remembrance. Wouk was extremely critical of Halsey's handling of the battle at Leyte Gulf, but also said he was too great a builder of naval morale to be retired in disgrace. (Chapter 92) Halsey was portrayed in the 1983 television miniseries adaptation of The Winds of War by Richard X. Slattery, and in the 1988 miniseries adaptation of War and Remembrance by Pat Hingle.

- Halsey has been portrayed in a number of other films and TV miniseries, played by Glenn Morshower (Pearl Harbor, 2001), Kenneth Tobey (MacArthur, 1977), Jack Diamond (Battle Stations, 1956), John Maxwell, (The Eternal Sea, 1955) and Morris Ankrum (Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, 1944).

- An "Admiral Halsey" is mentioned in the Paul and Linda McCartney song "Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey". The chorus of "hands across the water, heads across the sky" was a reference to the American aid programs of World War II. McCartney later specified that the second half of the song was indeed in honor of William Halsey.[70]

- On March 4, 1951, Halsey appeared as a mystery guest on episode No. 40 of the game show, What's My Line, where the panel correctly deduced his identity.[71]

- In the television series, McHale's Navy, one of Captain Binghamton's catchphrases whenever he would get frustrated with one of McHale's schemes was, "What in the name of Halsey is going on here?"

- Halsey is mentioned in the 1990 film The Hunt for Red October. Soviet submarine commander Marko Ramius, while engaged in battle with the Soviet attack submarine Konovalov, asks Jack Ryan what books he wrote for the CIA. Ryan mentions one about Admiral Halsey, entitled The Fighting Sailor (not to be confused with a real book of the same title); Ramius reveals his awareness of the book and expresses disdain for Ryan's assessment of Halsey, saying, "Your conclusions were all wrong, Ryan. Halsey acted stupidly."

- A character in Seth MacFarlane's The Orville is named Admiral Halsey, presumably after Admiral Halsey.

- In The Bridge on the River Kwai, William Holden's character, feigning madness as his excuse for impersonating an officer, says, "I'm getting worse, you know. Sometimes I think I'm Admiral Halsey."

- A former service area on the New Jersey Turnpike was named for Admiral William Halsey located by what is now Exit 13A in Elizabeth, New Jersey. Upon creation of the exit in 1982, this caused the obscuring of the service area as they both overlapped with each other, before the service area itself closed in 1994.

See also

Notes

- ↑ U.S. officers holding five-star rank never retire; they draw full active duty pay for life.[1]

- ↑ The "Big Blue Fleet" was the name given to the main fleet of the U.S. Navy in the Pacific. The term stems from pre-war planning, called the color plans because each nation included was given a color code name. In these potential plans the British navy was red, the German navy black, and so forth. The Imperial Japanese Navy was termed the "Orange Fleet". The U.S. fleet was the "Blue Fleet". The "Big Blue Fleet" was the massive fleet that the U.S. Navy anticipated they would win the war with. It was thought this fleet would largely come into being by late 1943, early 1944.[3][33]

References

Citations

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer C. (2011). The Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. pp. 1685. ISBN 978-1-85109-961-0.

- 1 2 Morison 1958, p. 183.

- 1 2 3 Potter 1985, p. 112.

- ↑ Wukovits 2010, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Hughes 2016, p. 16.

- ↑ Berger, Meyer (November 8, 1945). "Home Town Roars Salute to Halsey; The Commander of the Third Fleet Returns to His Hometown in New Jersey". The New York Times. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- ↑ Johnson, Bill (February 15, 1965). "Seven Society's Secret Still Secret". Washington Post. p. C8.

- ↑ Wukovits 2010, p. 9.

- ↑ Borneman 2012, p. 47.

- ↑ Wukovits 2010, p. 17.

- 1 2 3 NHHC Halsey 2019.

- ↑ Borneman 2012, p. 157.

- ↑ Morison 1948, p. 190.

- ↑ Wildenberg 2005. Wildenberg quotes Browning's thesis: "Every carrier we have knows what it means to be 'bopped' with all planes on deck, because her hands were tied by uncertainty as to her next move..."

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wukovits 2010.

- 1 2 "Books: The General and the Admiral". Time. November 10, 1947. Archived from the original on August 28, 2013.

- ↑ Millis 1947, p. 357.

- ↑ Halsey & Bryan 1947, pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Potter 1985.

- ↑ Potter 1976, p. 85.

- ↑ Potter 1976, p. 84.

- ↑ Potter 1976, p. 86.

- ↑ Potter 1985, p. 150.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 199–207.

- ↑ Frank 1990, pp. 368–378.

- ↑ Dull 1978, pp. 235–237.

- ↑ Frank 1990, pp. 335–336.

- ↑ "Admiral William Halsey". Time. November 30, 1942. cover. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ↑ Borneman 2012, p. 640.

- ↑ Halsey & Bryan 1947, p. 132.

- ↑ Seal, Jon; Ahn, Michael (March 2000). "An Interview with Joseph Jacob 'Joe' Foss". Microsoft Games Studios. Archived from the original on February 9, 2006. Retrieved August 3, 2011.

- ↑ Taylor 1991, p. 145.

- 1 2 Potter 1985, p. 221.

- ↑ Potter 2005, pp. 98–99.

- ↑ Parshall & Tully 2005, pp. 416–430.

- ↑ Cutler 1994, p. 209.

- ↑ Tuohy 2007, p. 323.

- ↑ Hone 2013, p. 71.

- 1 2 3 4 Willmott 2005, pp. 192–197.

- ↑ Potter 1985, pp. 376–380.

- ↑ Tillman, Barrett (July 2007). "William Bull Halsey: Legendary World War II Admiral". historynet.com. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- ↑ Drury & Clavin 2007, p. 270.

- ↑ Drury & Clavin 2007, pp. 15, 272; Melton 2007, p. 244.

- ↑ Drury & Clavin 2007, p. 15; Evans & Peattie 1997, p. 243.

- ↑ Willmott 1984, pp. 178–181.

- ↑ Utica Daily Press, February 20, 1945.

- ↑ Melton 2007, p. 270.

- ↑ Tolley 1983, p. 245.

- ↑ Buell 1974, pp. 435–436.

- ↑ Halsey & Bryan 1947, p. 69.

- ↑ Borneman 2012, pp. 73–74.

- ↑ Borneman 2012, pp. 344.

- ↑ Borneman 2012, pp. 74, 90.

- ↑ "William F. Halsey III, 88". Obituaries. Archived from the original on May 14, 2015. Retrieved July 18, 2014.

- ↑ Weaver, Tom. "Brett Halsey Interview", Eye on Science Fiction: 20 Interviews with Classic SF and Horror Filmmakers, McFarland, 2007.

- ↑ "Adm. Halsey dies at Fishers Island". The Day. (New London, Connecticut). Associated Press. August 17, 1959. p. 1.

- ↑ "Following Advance for Use Sunday, Aug. 16". KXNet.com North Dakota News.

- ↑ "'Bull' Halsey is buried". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). Associated Press. August 21, 1959. p. 2.

- ↑ Brady, James (2000). Flags of Our Fathers. Bantom Books. p. 579. ISBN 978-0-553-11133-0.

- ↑ "William Frederick Halsey, Jr". Military Times Hall of Valor. Archived from the original on September 2, 2012.

- ↑ Sudsbury, Elretta (1967). Jackrabbits to Jets: The History of North Island, San Diego, California. Neyenesch Printers, Inc.

- ↑ "Halsey Society".

- ↑ "Admiral William F. Halsey Jr. Leadership Academy". Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved August 8, 2011.

- ↑ "Halsey Terrace".

- ↑ Reidy, Jade (2013). Not Just Passing Through: the Making of Mt Roskill (2nd ed.). Auckland: Puketāpapa Local Board. p. 153. ISBN 978-1-927216-97-2. OCLC 889931177. Wikidata Q116775081.

- ↑ Alynia Rule. "Special Projects – The Florida Quest (Places, Names and Road Trip Games) – NIE WORLD". Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved August 8, 2011.

- ↑ History of Rock Creek Woods. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ↑ "Admiral Halsey Service Area". i95exitguide.com. Archived from the original on August 14, 2011. Retrieved August 8, 2011.

- ↑ Pishief, Elizabeth; Shirley, Brendan (August 2015). "Waikōwhai Coast Heritage Study" (PDF). Auckland Council. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ↑ McGee, Garry (2003). Band on the Run: A History of Paul McCartney and Wings. New York: Taylor Trade Publishing. p. 196. ISBN 0-87833-304-5.

- ↑ "Episode No. 40 Summary". TV.com. Archived from the original on December 19, 2010. Retrieved March 4, 2008.

Sources

- Borneman, Walter R. (2012). The Admirals: Nimitz, Halsey, Leahy and King – The Five-Star Admirals Who Won the War at Sea. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-09784-0.

- Buell, Thomas B. (1974). The Quiet Warrior, A Biography of Raymond A. Spruance. Little, Brown. ISBN 0-87021-562-0.

- Cutler, Thomas (1994). The Battle of Leyte Gulf: 23–26 October 1944. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-243-9.

- Drury, Robert; Clavin, Tom (2007). Halsey's Typhoon: The True Story of a Fighting Admiral, an Epic Storm, and an Untold Rescue. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-87113-948-1. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- Dull, Paul S. (1978). A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1941–1945. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-097-6.

- Evans, David; Peattie, Mark (1997). Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy 1887–1941. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-192-8.

- Frank, Richard (1990). Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-58875-9.

- Halsey, William F.; Bryan, Joseph III (1947). Admiral Halsey's Story. New York; London: Whittlesey House. OL 13528468M.

- Hone, Thomas C. (Winter 2013). "Replacing Battleships with Aircraft Carriers in the Pacific in World War II". Naval War College Review. 66 (1): 56–76. Archived from the original on April 12, 2017. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- Hughes, Thomas Alexander (2016). Admiral Bill Halsey: A Naval Life. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-04963-5.

- Melton, Buckner F. Jr. (2007). Sea Cobra, Admiral Halsey's Task Force and the Great Pacific Typhoon. Lyons Press. ISBN 978-1-59228-978-3. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- Millis, Walter (1947). This Is Pearl! The United States and Japan—1941. New York: William Morrow and Company. ISBN 978-0-837-15795-5.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1948). The Rising Sun in the Pacific 1931 – April 1942. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. 3. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company.

- ——— (1958). The Struggle for Guadalcanal, August 1942 – February 1943. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. 5. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-58305-3.

- Parshall, Jonathan; Tully, Anthony (2005). Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway. Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books. ISBN 1-57488-923-0.

- Potter, E. B. (2005). Admiral Arleigh Burke. U.S. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-692-6.

- ——— (1985). Bull Halsey. U.S. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-691-9.

- ——— (1976). Nimitz. U.S. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-492-9.

- Taylor, Theodore (1991) [Originally published 1954]. The Magnificent Mitscher. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-800-3.

- Tolley, Kemp (1983). Caviar and Commissars: the Experience of a U.S. Naval Officer in Stalin's Russia. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-407-4.

- Tuohy, William (2007). America's Fighting Admirals:Winning the War at Sea in World War II. Zenith Press. ISBN 978-0-7603-2985-6.

- Willmott, H. P. (1984). June, 1944. Poole, Dorset, UK: Blandford Press. ISBN 0-7137-1446-8.

- ——— (2005). "Six, The Great Day of Wrath". The Battle of Leyte Gulf: The Last Fleet Action. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34528-8.

- Wildenberg, Thomas (Winter 2005). "Midway: Sheer Luck or Better Doctrine?". Naval College War Review. 58 (1).

- Wukovits, John (2010). Admiral "Bull" Halsey – The Life and Wars of the Navy's Most Controversial Commander. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-60284-7.

- "Fleet Admiral William Frederick Halsey Jr". Naval History and Heritage Command. April 8, 2019. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

Further reading

- Dillard, Nancy R. (May 20, 1997). "Operational Leadership: A Case Study of Two Extremes during Operation Watchtower" (Academic report). Joint Military Operations Department, Naval War College. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved August 4, 2009.

- Drury, Robert; Clavin, Tom (December 28, 2006). "How Lieutenant Ford Saved His Ship". New York Times.

- Thomas, Evan (2006). Sea of Thunder: Four Commanders and the Last Great Naval Campaign. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-5221-8.

- Hughes, Thomas (January 2013). "Learning to Fight: Bill Halsey and the Early American Destroyer Force". Journal of Military History (77): 71–90.

- Mossman, B. C.; Stark, M. W. (1991). "Chapter XVIII: Fleet Admiral William F. Halsey Jr., Special Military Funeral, 16 – August 20, 1959". The Last Salute: Civil and Military Funeral, 1921–1969. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army. CMH Pub 90-1. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved July 12, 2010.

- Toll, Ian W. (2011). Pacific Crucible: War at Sea in the Pacific, 1941–1942. New York: W. W. Norton.

- ——— (2015). The Conquering Tide: War in the Pacific Islands, 1942–1944. New York: W. W. Norton.

- ——— (2020). Twilight of the Gods: War in the Western Pacific, 1944–1945. New York: W. W. Norton.