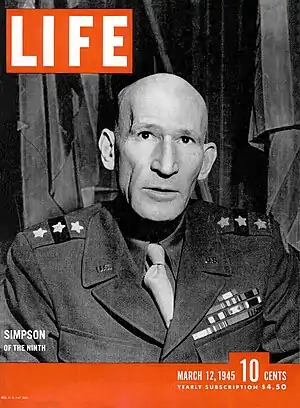

William Hood Simpson | |

|---|---|

General William Hood Simpson in 1959. | |

| Nickname(s) | "Big Simp"[1] |

| Born | May 18, 1888 Weatherford, Texas, United States |

| Died | August 15, 1980 (aged 92) San Antonio, Texas, United States |

| Buried | Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia, United States |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1909–1946 |

| Rank | |

| Service number | O-2645 |

| Unit | |

| Commands held | |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards |

|

General William Hood Simpson (May 18, 1888 – August 15, 1980) was a senior United States Army officer who served with distinction in both World War I and World War II. He is best known for being the Commanding General of the Ninth United States Army in northwest Europe during World War II.

A graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, where he was ranked 101st out of 103 in the class of 1909, Simpson served in the Philippines, where he participated in suppression of the Moro Rebellion, and in Mexico with the Pancho Villa Expedition in 1916. During World War I he saw active service in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive on the Western Front on the staff of the 33rd Division, for which he was awarded the Army Distinguished Service Medal and Silver Citation Star. Between the wars he served on staff postings, attended the Command and General Staff College and the Army War College, and commanded the 3rd Battalion, 12th Infantry Regiment.

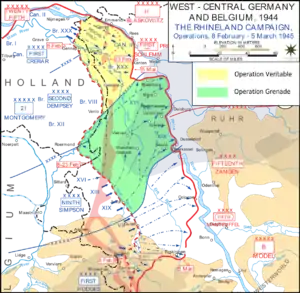

During World War II he commanded the 9th Infantry Regiment and was the assistant division commander of the 2nd Infantry Division. In succession he commanded the 35th and the 30th Infantry Divisions, the XII Corps, and the Fourth Army. In May 1944, with the three-star rank of lieutenant general, he assumed command of the Ninth Army. Simpson led the Ninth Army in the assault on Brest in September 1944, and the advance to the Roer River in November. During the Battle of the Bulge in December, Simpson's Ninth Army came under command of Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery's Anglo-Canadian 21st Army Group. After the battle was over in early 1945, the Ninth Army remained with Montgomery's 21st Army Group for Operation Grenade, the advance to the Rhine, and Operation Plunder, its crossing. On April 1 the Ninth Army made contact with the First Army, making a complete encirclement of the Ruhr, and on April 11, it reached the Elbe.

After the war ended, Simpson commanded the Second United States Army, and served in the Office of the Chief of Staff. He retired from the army in 1946. In retirement, he lived and worked in the San Antonio, Texas, area. He was a member of the board of directors of the Alamo National Bank, and succeeded General Walter Krueger as a member of the Board of Directors of the Chamber of Commerce of San Antonio. He died in the Brooke Army Medical Center on August 15, 1980, and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Early life and military career

William Hood Simpson was born on May 18, 1888, at Weatherford, Texas, the son of Edward J. Simpson, a rancher, and his wife Elizabeth née Hood, the daughter of Judge A. J. Hood, a prominent lawyer. His father and uncle had fought with the Confederate Army under Nathan Bedford Forrest in the American Civil War. He lived in Weatherford until he was five or six years old, when the family moved to Hood's ranch near Aledo, Texas. He did not start school until he was eight years old, when he started riding a horse several miles each day to the local school in Aledo.[2][3] He attended Hughey Turner Training School, a college-preparatory school, where he played high school football,[4] but did not graduate.[5]

Simpson decided to pursue a military career and attend the United States Military Academy (USMA) at West Point, New York.[6] He was friends with Fritz G. Lanham, the son of Samuel Lanham, the Governor of Texas (and a former law partner of Judge Hood). Through Lanham he was able to secure an appointment from his local Congressman, Oscar W. Gillespie. Competition was not fierce; only one other boy applied. As Simpson's academic credits were insufficient to qualify for automatic admission, Simpson had to sit an entrance examination at Fort Sam Houston in May 1905. A physical examination was conducted while he was there. He passed both, and was accepted into the class of 1909.[3][7]

On June 14, 1905, a month after he turned 17, Simpson entered West Point.[8] He found the curriculum difficult, and by the end of his first year, he stood 116th in a class that now numbered 120; 29 members of the class had dropped out.[9] He was poor at mathematics, but excelled at equitation, and by the end of his second year his standing had risen to 107th out of 108, then to 100th out of 107 by the end of his third.[10] When eight cadets, two of whom were from the class of 1909, were found guilty of hazing and suspended,[11] it fell to Simpson, as a cadet captain, to escort them from the academy grounds.[12] Simpson graduated on June 11, 1909, ranked 101st out of 103 in his class, and was commissioned as a second lieutenant of Infantry.[13] Fellow members of his class included Jacob L. Devers (39th),[14] George S. Patton (46th),[15][6] and Robert L. Eichelberger (68th),[16] all of whom eventually reached four-star rank, and John C. H. Lee (12th), and Delos C. Emmons (61st), who reached three-star rank.[17]

Early military career and World War I

Simpson's first assignment was with the 2nd Battalion, 6th Infantry Regiment, which was stationed at Fort Lincoln, North Dakota.[3] Soon after he joined in the regiment on September 11, 1909, it received orders to deploy to the Philippines. He embarked from San Francisco on January 5, 1910. He went to the island of Mindanao in the Philippines and participated in suppression of the Moro Rebellion. He returned to the United States with his regiment, arriving at the Presidio of San Francisco on July 10, 1912. The regiment moved to El Paso, Texas, between April 24 and May 1, 1914. Promoted to first lieutenant on July 1, 1916, he commanded Companies C and K in the Pancho Villa Expedition in 1916. On February 24, 1917, he became aide-de-camp to Brigadier General George Bell Jr., the commander of the El Paso Military District.[3]

Simpson was promoted to captain on May 15, 1917, a month after the American entry into World War I. He followed Bell on a tour of inspection of the British and French forces on the Western Front in September and October 1917.[18] They then returned to Camp Logan, Texas, where the 33rd Division was activated, with Bell, now a major general, as its first commander. The 33rd Division arrived in France in May 1918 and Simpson became its Assistant Chief of Staff (G-3), the staff member responsible for operations. He was promoted to major on June 7, 1918, and attended the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) Army General Staff College from June 15 to August 30. He returned to the 33rd Division as assistant to its G-2 (the staff member responsible for intelligence) on September 1, then became assistant to its G-3 on September 15. He became G-3 again on October 4, and participated in the Meuse–Argonne offensive. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel on November 5, and became the division's chief of staff on November 17, soon after World War I ended on November 11, 1918.[13] For his services during the war he was awarded the Army Distinguished Service Medal and Silver Citation Star,[6] and the French Croix de guerre and Legion of Honour in the grade of Chevalier.[19] The citation for his Army DSM reads:

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Army Distinguished Service Medal to Lieutenant Colonel (Infantry) William Hood Simpson, United States Army, for exceptionally meritorious and distinguished services to the Government of the United States, in a duty of great responsibility during World War I, as Assistant Chief of Staff, 33d Division, during the Meuse-Argonne offensive and later as Chief of Staff of this division.[20]

Between the wars

Upon returning to the United States in May 1919, Simpson was posted to the 6th Division at Camp Grant, Illinois, as its chief of staff from June 15, 1919, to August 25, 1920. He reverted to his substantive rank of captain on June 30, 1920, but was promoted to major again the following day. From August 26 to December 30, he served as its assistant chief of staff (G-3). He served in Washington, DC, in the Office of the Chief of Infantry from January 1, 1921, to August 1, 1923.[19] In El Paso, Texas on Christmas Eve, 1921, he married Ruth Krakauer, an English-born widow whom he had first met while at West Point.[21][22][6] From September 1, 1923, to May 28, 1924, he was a student officer in the Advanced Course at the Infantry School at Fort Benning, Georgia. He then attended the United States Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, from August 15, 1924, to June 19, 1925, when he was graduated as a distinguished graduate.[19][6]

On July 1, 1925, Simpson assumed command of the 3rd Battalion, 12th Infantry Regiment, at Camp Meade, Maryland, and later Fort Washington, Maryland; his tour in command also included duty at the Sesquicentennial Exposition in Philadelphia from May to November 1926. He then attended the United States Army War College from August 15, 1927, to June 30, 1928. Upon graduation, he was assigned to the War Department General Staff in Washington, D.C.,[19] where he worked in the Latin American section of the G-2 branch.[23] On June 20, 1932, he became Professor of Military Science and Tactics at Pomona College in Claremont, California, and was promoted to lieutenant colonel again from October 1, 1934.[24] This posting also included duty as the Army representative at the California Pacific International Exposition in 1935. He then became an instructor at the Army War College in the G-4 Division from August 12, 1936, to June 24, 1937, and was director of its G-2 Division until August 25, 1940, with the rank of colonel from September 1, 1938.[25][24]

World War II

On August 30, 1940, Simpson was appointed to command the 9th Infantry Regiment at Fort Sam Houston, Texas. He was promoted to brigadier general on October 1, 1940, and served as the Assistant Division Commander (ADC) of the 2nd Infantry Division from October 5, 1940, to April 4, 1941, when Fred L. Walker succeeded him. From April to September 1941 he was the first commander of the country's largest Infantry Replacement Training Center, Camp Wolters, located in Mineral Wells, Texas. He received a promotion to temporary major general on September 29, 1941, and commanded the 35th Infantry Division, an Army National Guard formation, at Camp Robinson, Arkansas, from October 15, 1941, to April 5, 1942,[26] for which he was awarded the Legion of Merit.[20] He then commanded the 30th Infantry Division, another Army National Guard formation, at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, until Leland Hobbs took command. On August 31, 1942, he took command of the newly created XII Corps.[26]

Simpson commanded the Fourth United States Army from September 29, 1943, to May 8, 1944, with the three-star rank of lieutenant general as of October 13, 1943.[26] Fourth Army was re-formed when the combined headquarters of the Western Defense Command and Fourth Army were separated. A cadre was provided by the Western Defense Command, but all senior officers were approved or selected by Simpson. He brought his chief of staff, Colonel James E. Moore with him from XII Corps. Moore had previously served with him as chief of staff of the 35th and 30th Infantry Divisions. The Fourth Army headquarters was initially in San Jose, California, and it functioned as a training army. In search of more office space, the headquarters was moved to the Presidio of Monterey, California on November 1, and then to Fort Sam Houston in January 1944, when it took over the training mission of the Third United States Army, which had moved overseas.[27]

More personnel arrived in early 1944, enabling the Fourth Army to be split into a training army (the Fourth) and a headquarters to be deployed overseas, the Eighth, which was activated on May 5, 1944. Simpson and most of his staff became part of the Eighth Army headquarters. An advance party of the headquarters flew to the UK on May 11, and Simpson met with the commander of the European Theater of Operations, United States Army, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, an Army War College classmate. At Eisenhower's request, Simpson's command was redesignated the Ninth United States Army to avoid confusion with the British Eighth Army. The main body of Ninth Army embarked for the UK on the ocean liner RMS Queen Elizabeth on June 22.[28][29] Simpson observed the abortive start of Operation Cobra on July 24 with Lieutenant Generals Courtney Hodges and Lewis H. Brereton. They were forced to take shelter as errant American bombs dropped around them.[30] Lieutenant General Lesley J. McNair invited Simpson to watch the repeat of the bombardment with him the following day, but Simpson elected to return to his headquarters in England. Once again bombs fell short, and McNair was killed.[31]

The Ninth Army headquarters moved to France, as it landed at Utah Beach on August 29 and 30. It became active as part of Lieutenant General Omar Bradley's 12th Army Group on September 5, when it took over command of the US forces in Brittany from Lieutenant General George S. Patton Jr.'s Third Army.[32] Simpson's first task was the capture of Brest. To overcome strong natural and man-made defenses, Simpson chose to employ overwhelming firepower. There were sufficient artillery pieces in the area, but not sufficient ammunition, especially for the heavier pieces. Over a two-week period, 40,000 long tons (41,000 t) of artillery ammunition was brought forward from dumps in Normandy and the UK.[33] The battle commenced on September 8, and after much hard fighting the city was liberated on September 20, 1944.[34]

Simpson moved his headquarters to Arlon, where it opened on October 2, and two days later the Ninth Army relieved First Army in the southern portion of its line, taking over the center of the 12th Army Group's front in the Ardennes between the First and Third Armies.[35] The stay at Arlon was brief; on October 10, Simpson received word that Ninth Army was to take over the northern sector of the 12th Army Group's front adjoining Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery's Anglo-Canadian 21st Army Group. This was a consequence of Eisenhower's decision to reinforce that sector. The plan was for the Ninth Army to envelop the Ruhr industrial area to the north while First Army enveloped it to the south.[36][37]

Reflecting on the decision later, Bradley opined that the "uncommonly normal" Ninth Army staff collaborated with the 21st Army Group better than the more temperamental First Army staff did.[38] Ninth Army's attack on the Siegfried Line north of Aachen commenced on November 16, heralded by artillery and aerial bombardment that included attacks by heavy bombers of the Eighth Air Force and RAF Bomber Command.[39] Progress was slow and costly. Simpson's offensive ended on December 14, but on the Roer River rather than the Rhine, due to the flooding threat posed by Roer dams upstream.[40]

The Urft Dam (Urfttalsperre) held 161,000,000 cubic feet (4,550,000 m3) of water, and the Rur Dam (Schwammenauel) held another 2.31×109 cubic feet (65,500,000 m3). The Germans could demolish them to create a disastrous flood. Alternatively, through controlled demolition, they could release 7,100 cubic feet per second (202 m3/s). This would put the river into a flood condition that would cause it to rise by 3 feet (0.91 m), increase the speed of the current by 10 feet per second (3.0 m/s) and increase the width to 1,200 feet (370 m). This would preclude a crossing attempt for ten to twelve days.[41]

Eisenhower was anxious about accepting an army commander without operational experience in the war, but senior officers with such experience were few in May 1944. By October 1, however, Eisenhower was sufficiently impressed by Simpson's performance to write to the Chief of Staff of the Army, General George C. Marshall, and recommend that Simpson's temporary rank of lieutenant general be made substantive.[42] According to Colonel Armistead D. Mead, Simpson's G-3 (Operations) officer:

General Simpson's genius lay in his charismatic manner, his command presence, his ability to listen, his unfailing use of his staff to check things out before making decisions, and his way of making all hands feel that they were important to him and to the army... I have never known a commander to make better use of his staff than General Simpson.[43]

During the crisis of the Battle of the Bulge, the Ninth Army came under Montgomery's command on December 20. The Ninth Army took no part in the battle, but was stripped of eight divisions to reinforce the First Army, and took over part of its front. After the battle was over in early 1945, the Ninth Army remained with Montgomery's 21st Army Group for the final attack into Germany.[40][44] For Operation Grenade, the crossing of the Roer, the Ninth Army was reinforced, its strength increased from five to twelve divisions.[45] The major obstacle to the advance was the river itself, as the dams were still in German hands.[41]

The British Second Army commenced Operation Veritable, the northern part of a pincer movement to clear the Rhineland, on February 8, 1945. Montgomery's plan was for Operation Grenade, scheduled to commence on February 10, 1945, to form the southern part of the pincer, but there was still no word of the capture of the Roer dams by the First Army. Montgomery left the decision of whether to delay Operation Grenade up to Simpson, but postponement would make the task of both the British troops already fighting more difficult, and increase the risk that the Germans would detect the Ninth Army's preparations. Simpson watched the river slowly rise, but could not be certain whether it was the result of German demolition or increased flow due to snow melt. Finally, he postponed the attack. His decision was the correct one; the waters continued to rise and the river level was up 5 feet (1.5 m) on February 9 and 10.[46]

Operation Grenade was finally launched on February 23, even though the water level had not yet completely returned to normal.[47] The attack was successfully concluded on March 5, with the Rhine reached.[48] Next came Operation Plunder, the 21st Army Group's crossing of the Rhine; the Ninth Army's part was called Operation Flashpoint.[49] The Rhine was crossed on March 24, 1945.[50] On April 1 the Ninth Army made contact with First Army, making a complete encirclement of the Ruhr.[51] Three days later, the Ninth Army reverted to the control of Bradley's 12th Army Group.[52] On April 11, the Ninth Army reached the Elbe.[53]

On March 10, Montgomery had written to Simpson:

I would like to tell you how very pleased I have been with everything the Ninth Army has done. The operations were planned and carried through with great skill and energy. It has fallen to my lot to be mixed up with a good deal of fighting since I took command of the Eighth Army before Alamein in 1942; and the experience I have gained enables me to judge pretty well the military calibre of Armies. I can truthfully say that the operations of the Ninth Army, since 23 February last, have been up to the best standards.[42]

.jpg.webp)

After Victory in Europe Day, the Ninth Army participated in the occupation of Germany. On May 6, it took over the First Army's units, allowing the First Army headquarters to redeploy to the Pacific.[54] Further regrouping followed, as most of the area covered was earmarked to be administered by the UK or Soviet Union. On June 15, all units of the Ninth Army were handed over to the Seventh United States Army, and Ninth Army headquarters prepared to redeploy to China.[55] Simpson flew to China, where he met with Lieutenant General Albert C. Wedemeyer, the American commander there. Simpson was informed that he would become the Commanding General, Field Forces, and deputy theater commander. The end of the war in Asia came before this occurred.[56]

Eisenhower summarized his experience with Simpson as follows:

If Simpson ever made a mistake as an Army Commander, it never came to my attention. After the war I learned that he had for some years suffered from a serious stomach disorder, but I would never have suspected during hostilities. Alert, intelligent, and professionally capable, he was the type of leader that American soldiers deserve. In view of his brilliant service, it was unfortunate that shortly after the war ill-health forced his retirement before he was promoted to four-star grade, which he had so clearly earned.[57]

For his services as commander of the Ninth Army, Simpson was awarded the Bronze Star Medal and a second Army Distinguished Service Medal. He also garnered foreign decorations that included being made a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire by the UK, a Grand Commander of the Order of Orange-Nassau by the Netherlands, and a Grand Officer of the Order of Leopold with palm by Belgium. He also received the Legion of Honor and the Croix de Guerre 1939–1945 from France, the Soviet Union's Order of Kutuzov, and the Croix de Guerre 1940 with palm from Belgium.[20][26]

Later life

After the war ended, Simpson commanded the Memphis, Tennessee-based Second United States Army from October 11 to November 14, 1945. He then returned to Washington, DC, working in the Office of the Chief of Staff as a member of the Military Intelligence Board, and President of the War Department Reorganization Board from November 15, 1945, until April 4, 1946. He retired from the army with a physical disability on November 30, 1946.[26] On August 4, 1954, he was promoted to full general on the retired list by a special Act of Congress that advanced officers who had commanded armies or the equivalent to that rank.[58][59]

After retirement, Simpson lived and worked in the San Antonio, Texas, area. He was a member of the board of directors of the Alamo National Bank, and succeeded General Walter Krueger as a member of the Board of Directors of the Chamber of Commerce of San Antonio. He was also chairman of the board of the Alamo chapter of the Association of the United States Army, and spearheaded a drive to raise $750,000 for the construction of the Santa Rosa Children's Hospital.[5][21]

His wife Ruth died in 1971, and soon thereafter, Simpson moved into the Menger Hotel in downtown San Antonio, where he was very popular with the staff. He suffered from phlebitis and neuritis, and was generally confined to his room. In 1978, at the age of 90, he met Catherine Louise (Kay) Berman, a retired civil-service worker from a military family 33 years his junior, and the two were married on April 9, 1978. They moved out of the Menger Hotel and into a home they built in Windcrest, Texas.[21][60]

Simpson died in the Brooke Army Medical Center on August 15, 1980,[22] and was buried alongside his first wife Ruth in Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.[61]

Military decorations

Dates of rank

| Insignia | Rank | Component | Date | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No insignia in 1909 | Second Lieutenant | 6th Infantry Regiment | June 11, 1909 | [13] |

| First Lieutenant | 6th Infantry Regiment | July 1, 1916 | [13] | |

| Captain | Infantry | May 15, 1917 | [13] | |

| Major | National Army | June 7, 1918 | [13] | |

| Lieutenant Colonel | National Army | November 5, 1918 | [13] | |

| Captain (reverted) | Infantry | June 30, 1920 | [13] | |

| Major | Infantry | July 1, 1920 | [19] | |

| Lieutenant Colonel | Infantry | October 1, 1934 | [25] | |

| Colonel | Infantry | September 1, 1938 | [25] | |

| Brigadier General | Army of the United States | October 1, 1940 | [25] | |

| Major General | Army of the United States | September 29, 1941 | [26] | |

| Lieutenant General | Army of the United States | October 13, 1943 | [26] | |

| Brigadier General | Regular Army | February 1, 1944 | [26] | |

| Major General | Regular Army | April 11, 1946 | [26] | |

| Lieutenant General | Retired List | November 30, 1946 | [26] | |

| General | Retired List | August 4, 1954 | [63][59] |

Notes

- ↑ English 2009, p. 137.

- ↑ Stone 1971, pp. 6–7.

- 1 2 3 4 Buerkle, Ruth C. (June 30, 1976). "General William Hood Simpson, United States Army, Retired". Bexar County Historical Commission Oral History Program. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ↑ Bartoli & McClurkin 2012, p. 59.

- 1 2 Buerkle, Ruth C. (July 7, 1976). "General William Hood Simpson, United States Army, Retired". Bexar County Historical Commission Oral History Program. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 English 2009, p. 139.

- ↑ Stone 1971, pp. 5–11.

- ↑ Stone 1971, p. 14.

- ↑ Stone 1971, p. 23.

- ↑ Stone 1971, pp. 26–29.

- ↑ "Cadets Dismissed from West Point". San Francisco Call. Vol. 104, no. 84. August 23, 1908. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

- ↑ Stone 1971, pp. 30–32.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Cullum 1920, p. 1466.

- ↑ Cullum 1920, p. 1429.

- ↑ Cullum 1920, p. 1433.

- ↑ Cullum 1920, p. 1446.

- ↑ Cullum 1920, pp. 1412, 4442.

- ↑ English 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Cullum 1930, pp. 862–863.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "William Simpson – Recipient". Hall of Valor Project. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- 1 2 3 "William Hood Simpson". Assembly. 40 (4): 116–117. March 1982. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- 1 2 Hull, Michael D. (December 31, 2018). "The U.S. Ninth Army's Breakout: Crossing the Roer and the Rhine". Warfare History Network. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- ↑ English 2009, pp. 139–140.

- 1 2 English 2009, p. 140.

- 1 2 3 4 Cullum 1940, p. 225.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Cullum 1950, p. 138.

- ↑ Parker & Thompson 1947, pp. 15–17.

- ↑ Stone 1974, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Parker & Thompson 1947, pp. 15–18.

- ↑ Stone 1974, pp. 22–24.

- ↑ Stone 1974, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Parker & Thompson 1947, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Parker & Thompson 1947, pp. 27–28.

- ↑ Parker & Thompson 1947, pp. 30–35.

- ↑ Parker & Thompson 1947, pp. 55–56.

- ↑ Parker & Thompson 1947, pp. 65–66.

- ↑ Stone 1974, pp. 103–104, 112–113.

- ↑ Bradley 1951, p. 422.

- ↑ Parker & Thompson 1947, p. 86.

- 1 2 Stone 1974, pp. 126–128.

- 1 2 Parker & Thompson 1947, pp. 133–134.

- 1 2 Stone 1981, p. 50.

- ↑ Stone 1981, p. 47.

- ↑ Parker & Thompson 1947, pp. 117–118.

- ↑ Stone 1974, p. 134.

- ↑ Stone 1974, pp. 158–163.

- ↑ Parker & Thompson 1947, p. 166.

- ↑ Parker & Thompson 1947, p. 191.

- ↑ Parker & Thompson 1947, p. 210.

- ↑ Parker & Thompson 1947, p. 243.

- ↑ Parker & Thompson 1947, p. 269.

- ↑ Parker & Thompson 1947, p. 274.

- ↑ Parker & Thompson 1947, p. 298.

- ↑ Parker & Thompson 1947, p. 332.

- ↑ Parker & Thompson 1947, pp. 358–361.

- ↑ Parker & Thompson 1947, pp. 363–364.

- ↑ Eisenhower 1997, p. 376.

- ↑ "Front and Center". The Army Combat Forces Journal. 5 (2): 3. September 1954. ISSN 0271-7336. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- 1 2 Pub. L. 83–508

- ↑ Williams 2000, pp. 172–175.

- ↑ "William H. Simpson". Arlington National Cemetery. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "General William Hood Simpson". The Portal to Texas History. 1959.

- ↑ Young 1959, p. 328.

References

- Bartoli, Jonelle Ryan; McClurkin, Brenda S. (2012). Weatherford: The Early Years. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-8549-9. OCLC 769988267.

- Bradley, Omar (1951). A Soldier's Story. New York: Henry Holt. OCLC 981308947.

- Cullum, George W. (1920). Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the US Military Academy at West Point New York since its Establishment in 1802: Supplement Volume VI 1910–1920. Chicago, Illinois: R. R. Donnelly and Sons, The Lakeside Press. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- Cullum, George W. (1930). Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the US Military Academy at West Point New York Since Its Establishment in 1802: Supplement Volume VII 1920–1930. Chicago: R. R. Donnelly and Sons, The Lakeside Press. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- Cullum, George W. (1940). Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the US Military Academy at West Point New York Since Its Establishment in 1802: Supplement Volume VIII 1930–1940. Chicago: R. R. Donnelly and Sons, The Lakeside Press. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- Cullum, George W. (1950). Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the US Military Academy at West Point New York since its Establishment in 1802: Supplement Volume IX 1940–1950. Chicago, Illinois: R. R. Donnelly and Sons, The Lakeside Press. Retrieved October 13, 2015.

- Eisenhower, Dwight D. (1997) [1948]. Crusade in Europe. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins Press. ISBN 0-8018-5668-X. OCLC 945382261.

- English, John A. (2009). Patton's Peers: The Forgotten Allied Field Army Commanders of the Western Front, 1944−45. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0501-1. OCLC 870994690.

- Parker, Theodore W.; Thompson, William J. (1947). Conquer: The Story of Ninth Army. Washington, DC: Infantry Journal. OCLC 2522151. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

- Stone, Thomas R. (1971). William H. Simpson: A General's General (PDF) (MA). Rice University. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

- Stone, Thomas R. (1974). He Had the Guts to Say No: A Military Biography of William H. Simpson: A General's General (PDF) (PhD). Rice University. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

- Stone, Thomas R. (1981). "General William H. Simpson-Unsung commander of U.S. 9th Army" (PDF). Parameters. U.S. Army War College. XI (2): 44–52. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- Williams, Docia Schultz (2000). The History and Mystery of the Menger Hotel. Plano, Texas: Republic of Texas Press. ISBN 978-1-55622-792-9. OCLC 1002200224.

- Young, Gordon Russell (1959). The Army Almanac: A Book of Facts Concerning the United States Army. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole. OCLC 474534421.