William Goebel | |

|---|---|

| |

| 34th Governor of Kentucky | |

| In office January 31, 1900 – February 3, 1900 | |

| Lieutenant | J. C. W. Beckham |

| Preceded by | William Taylor |

| Succeeded by | J. C. W. Beckham |

| President pro tempore of the Kentucky Senate | |

| In office 1896–1900 | |

| Member of the Kentucky Senate from the 24th district | |

| In office December 30, 1887 – January 31, 1900 | |

| Preceded by | James William Bryan |

| Succeeded by | Robert H. Fleming |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Wilhelm Justus Goebel January 4, 1856 Sullivan County, Pennsylvania, U.S.[1][2] or Albany Township, Pennsylvania, U.S.[3] |

| Died | February 3, 1900 (aged 44) Frankfort, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Relatives | Justus Goebel (brother) |

| Education | Hollingsworth Business College University of Cincinnati (LLB) Kenyon College |

| Signature |  |

William Justus Goebel (January 4, 1856 – February 3, 1900) was an American Democratic politician who served as the 34th governor of Kentucky for four days, having been sworn in on his deathbed a day after being shot by an assassin. Goebel remains the only state governor in the United States to be assassinated while in office.

Goebel was born to Wilhelm and Augusta Goebel (née Groenkle), German immigrants from Hanover. He studied at the Hollingsworth Business College in the mid-1870s and became an apprentice at John W. Stevenson's law firm. While Goebel lacked the social qualities like public speaking that are common with politicians, various authors referred to him as an intellectual man. He served in the Kentucky Senate, campaigning for populist causes like railroad regulation, which won him many allies and supporters.

In 1895, Goebel engaged in a duel with John Lawrence Sandford, a former Confederate general staff officer turned cashier. According to the witnesses, both men then drew their pistols, but no one was sure who fired first. Sandford was killed; Goebel pleaded self-defense and was acquitted.

During the 1899 Kentucky gubernatorial election, Goebel divided his party with his political tactics to win the nomination for governorship at a time when Kentucky Republicans were gaining strength, having elected the party's first governor four years previously. These dynamics led to a close contest between Goebel and William S. Taylor. In the politically chaotic climate that resulted, Goebel was declared as having won the election, but was assassinated and died after three days in office. Everyone charged in connection with the murder was either acquitted or eventually pardoned, and the identity of his assassin remains unknown.

Early life

Heritage and career

Wilhelm Justus Goebel was born January 4, 1856, to Wilhelm and Augusta Goebel (née Groenkle)—immigrants from Hanover, Germany—in Pennsylvania.[lower-alpha 1] The eldest of four children, he was two months premature and weighed less than 3 pounds (1.4 kg).[4] His father served as a private in Company B, 82nd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, during the American Civil War, and Goebel's mother raised her children alone, teaching them much about their German heritage. Wilhelm spoke German until the age of six, but he embraced American culture, adopting the English spelling of his name as "William".[5]

After being discharged from the army in 1863, Goebel's father moved his family to Covington, Kentucky.[6] Goebel attended school in Covington and was then apprenticed to a jeweler in Cincinnati, Ohio.[7] After a brief time at Hollingsworth Business College in mid 1870s, he became an apprentice in the law firm of John W. Stevenson, who had served as governor of Kentucky from 1867 to 1871. Goebel eventually became Stevenson's partner and executor of his estate.[8] Goebel graduated from Cincinnati Law School in 1877,[6] and enrolled at the Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio, before joining the practice of Kentucky state representative John G. Carlisle. He then rejoined Stevenson in Covington in 1883, after the death of Stevenson's previous partner.[2]

Personal characteristics

According to author James C. Klotter, Goebel was not known as a particularly genial person in public. He belonged to few social organizations and greeted none but his closest friends with a smile or handshake. He was rarely linked romantically with a woman[9] and was the only governor of Kentucky who never married.[1][6] Journalist Irvin S. Cobb remarked, "I never saw a man who, physically, so closely suggested the reptilian as this man did."[10] Others commented on his "contemptuous" lips, "sharp" nose, and "humorless" eyes.[10] Goebel was not a gifted public speaker, often eschewing flowery imagery and relying on his deep, powerful voice and forceful delivery to drive home his points. Klotter wrote, "When coupled to somewhat demagogic appeals and to an occasional phrase that stirred emotions, this delivery made for an effective speech, but never more than an average one."[10] While lacking in the social qualities common to politicians, one characteristic that served Goebel well in the political arena was his intellect. Goebel was well-read, and supporters and opponents both conceded that his mental prowess was impressive. Cobb concluded that he had never been more impressed with a man's intellect than he had been with Goebel's.[10]

Political career

Kentucky Senate

In 1887, James William Bryan vacated his seat in the Kentucky Senate to pursue the office of lieutenant governor. Goebel decided to seek election to the vacant seat representing Covington.[6] He campaigned on the platform of railroad regulation and labor causes. Like Stevenson, he insisted on the right of the people to control chartered corporations.[6][11] The Union Labor Party had risen to power in the area with a platform similar to Goebel's. However, while Goebel had to stick close to his allies in the Democratic Party, the Union Labor Party courted the votes of both Democrats and Republicans and made the election close, which was decided in Goebel's favor by just 56 votes.[12] He was later sworn in on December 30.[13] During his first term as senator, the State Railroad Commission increased to over $3,000,000[lower-alpha 2] tax evaluation on the property of Louisville and Nashville Railroad. A proposal from pro-railroad legislators in the Kentucky House of Representatives to abolish Kentucky's Railroad Commission was passed and sent to the Senate. Cassius Marcellus Clay responded by proposing a committee to investigate lobbying by the railroad industry. Goebel served on the committee, which uncovered significant violations by the railroad lobby.[14] He also helped defeat the bill to abolish the Railroad Commission in the Senate. These actions increased his popularity and he was elected senator unopposed in 1889 for a full term.[15] Goebel was well able to broker deals with fellow lawmakers and was equally able and willing to break the deals if a better deal came along. His tendency to use the state's political machinery to advance his agenda earned him the nickname "William the Conqueror".[16]

Goebel served as a delegate to Kentucky's fourth constitutional convention in 1890,[17] which produced the current Constitution of Kentucky.[18] Despite being a delegate, Goebel showed little interest in participating in the process of creating a new Constitution. The convention was in session for approximately 250 days, but Goebel was present for approximately only 100 days.[19] However, he did secure the inclusion of the Railroad Commission in the new Constitution. As a Constitutional entity, the Commission could only be abolished by an amendment ratified by a popular vote. This effectively protected the Commission from ever being unilaterally dismantled by the General Assembly.[20] Klotter wrote, "Goebel used the constitution as a vehicle to enact laws which he had not been able to pass in the more conservative legislature."[21] Goebel won another term in 1893 by a three-to-one margin over his Republican opponent.[22] By 1894, he had been elected as the President pro tempore of the Kentucky Senate.[6]

Duel with John Sandford

In 1895, Goebel engaged in what many observers considered to be a duel with John Lawrence Sandford. Sandford, a former Confederate general staff officer turned cashier, had clashed with Goebel before. Goebel's successful campaign to remove tolls from some of Kentucky's turnpikes cost Sandford a large amount of money. Many believed that Sandford had blocked Goebel's appointment to the Kentucky Court of Appeals, in retaliation.[23] Incensed, Goebel had written an article in a local newspaper referring to Sandford as "Gonorrhea John."[24] On April 11, 1895, Goebel and two acquaintances went to Covington to cash a check. Goebel suggested they avoid Sandford's bank, but Sandford, standing outside the bank, spoke to the men before they could cross the street to a different bank. Sandford greeted Goebel's friends, offering them his left hand. However, Goebel noticed that Sandford's right hand was on a pistol concealed in his pocket. Having come armed himself, Goebel clutched his revolver in his pocket.[25] Sandford confronted Goebel and said, "I understand that you assume authorship of that article." "I do", replied Goebel.[25]

The shooting took place at 1:30 p.m. According to the witnesses, both men then drew their pistols, but no one was sure which had fired first. One of the witnesses – W. J. Hendricks, the attorney general of Kentucky, said "I don't know who shot first, the shots were so close together."[26] Another witness, Frank P. Helm, said "I was right up against them and really thought at first that I had, myself, been shot."[26] Sandford's bullet passed through Goebel's coat and ripped his trousers, but left him uninjured. Goebel's shot fatally struck Sandford in the head; Sandford died five hours later.[23] Goebel pleaded self-defense and was acquitted.[27] The acquittal was significant because the Kentucky constitution prohibited dueling. If Goebel had been convicted of dueling, he would have been ineligible to hold any public office.[28] The shooting made Goebel unpopular among Kentucky's Confederate veterans, who also noted his non-southern background and his father's service in the Union army.[6]

Goebel Election Law

Kentucky Democrats, who controlled the General Assembly believed that county election commissioners had been unfair in selecting local election officials, and had contributed to the election of Republican governor William O. Bradley in 1895. Goebel proposed a bill, known as the "Goebel Election Law", which passed along strict party lines and over Governor Bradley's veto, created a three-member state election commission, appointed by the General Assembly, to choose the county election commissioners. It allowed the Democratic-controlled General Assembly to appoint only Democrats to the election commission.[29] Many voters decried the bill as a self-serving attempt by Goebel to increase his political power, and the election board remained a controversial issue until its abolition in a special session of the legislature in 1900. Goebel became the subject of much opposition from constituencies of both parties in Kentucky after the passage of the law.[30]

Gubernatorial election of 1899

In 1896, when William Jennings Bryan electrified the Democratic National Convention with his Cross of Gold speech and won the nomination for president, many delegates from Kentucky bolted the convention. Various Kentuckian politicians believed that free silver was a populist idea, and it did not belong to the Democratic Party. Subsequently, Republican William McKinley won the 1896 presidential election, carrying Kentucky. Author Nicholas C. Burckel believed that this set the stage for "horripilating gubernatorial election of 1899".[31] Three men sought the Democratic nomination for governor at the 1899 party convention in Louisville – Goebel, Parker Watkins Hardin, and William Johnson Stone.[32] When Hardin appeared to be the front-runner for the nomination, Stone and Goebel agreed to work together against him.[33] They concluded that Stone's supporters would endorse whomever Goebel picked to preside over the convention. In exchange, half the delegates from Louisville, who were pledged to Goebel, would vote to nominate Stone. Goebel would then drop out of the race, but would name many of the other officials on the ticket.[34] Both men agreed that, should one of them be defeated or withdraw from the race, they would encourage their delegates to vote for the other rather than support Hardin. As word of the plan spread, Hardin dropped out of the race, believing he would be beaten by the Stone–Goebel alliance. When the convention convened on June 24, several chaotic ballots resulted in no clear majority for anyone, and Goebel's hand-picked chairman announced the man with the lowest vote total in the next canvass would be dropped, which turned out to be Stone. This put Stone's supporters in a difficult position, and were forced to choose between Hardin, who was seen as a pawn of the railroads, or Goebel. Enough of them sided with Goebel to give him the nomination. Goebel's tactics, while not illegal, were unpopular and divided the party.[35] A disgruntled faction calling themselves the "Honest Election Democrats" held a separate convention in Lexington and nominated John Y. Brown as their gubernatorial candidate.[36]

Republican William S. Taylor defeated both Democratic candidates in the general election, but his margin over Goebel was only 2,383 votes.[37][38][39] Democrats in the General Assembly began making accusations of voting irregularities in some counties, but in a surprise decision, the Board of Elections created by the Goebel Election Law, manned by three hand-picked pro-Goebel Democrats, ruled 2–1 that the disputed ballots should count, saying the law gave them no legal power to reverse the official county results and that under the Kentucky Constitution the power to review the election lay in the General Assembly. The Assembly then invalidated enough Republican ballots to give the election to Goebel. The Assembly's Republican minority was incensed, as were voters in traditionally Republican districts. For several days, the state hovered on the brink of a possible civil war.[40]

Assassination and legacy

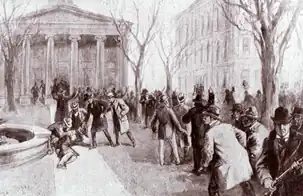

Shooting and death

With the election results still being in dispute, Goebel was warned of a rumored assassination plot against him. Nevertheless, flanked by two bodyguards, Goebel walked to the Old State Capitol on the morning of January 30, 1900. Conflicting reports describe what happened next, but either five or six shots were fired from the nearby State Building, one striking Goebel in the chest, seriously wounding him. Taylor, serving as Governor pending a final decision on the election, called out the militia and ordered the General Assembly into a special session in London, Kentucky – a Republican area. The Republican minority obeyed the call, and went to London. Democrats resisted the move, many going instead to Louisville. Both groups claimed authority, but the Republicans were too few to muster a quorum.[41][42] That evening, the day after being shot, Goebel was sworn in as Governor.[43] In his only official act, Goebel signed a proclamation to dissolve the militia called up by Taylor, which was ignored by the militia's Republican commander. Despite the care of 18 physicians, Goebel died the afternoon of February 3, 1900.[44] Journalists recalled his last words as "Tell my friends to be brave, fearless, and loyal to the common people."[45] Skeptic Irvin S. Cobb uncovered another story from some in the room at the time. On having eaten his last meal, the governor supposedly remarked "Doc, that was a damned bad oyster."[45] Goebel remains the only American governor ever assassinated while in office.[41][46] In respect of Goebel's displeasure with the Louisville and Nashville Railroad, his body was transported not by the L&N direct line, but circuitously from his hometown of Covington north across the Ohio River to Cincinnati, and then south to Frankfort on the Queen and Crescent Railroad.[47]

Amid the controversy that had resulted in Goebel's assassination, the Kentucky Court of Appeals ruled that the General Assembly had acted legally in declaring Goebel the winner of the election. That decision was appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States. Arguments were presented in the case Taylor v. Beckham on April 30, 1900, but on May 21, the justices decided 8–1 not to hear the case, allowing the Court of Appeals' decision to stand.[48] Goebel's lieutenant governor J. C. W. Beckham ascended to the governorship.[49]

Trials, investigations, and legacy

During the ensuing investigation of Goebel's assassination, suspicion naturally fell on deposed Governor Taylor, who had promptly fled to Indianapolis, under the looming threat of indictment. The governor of Indiana refused to extradite Taylor, and thus he was never questioned about his knowledge of the plot to kill Goebel. Ultimately, in 1909, Taylor was pardoned by Beckham's successor, Republican governor Augustus E. Willson.[50] However, a total of sixteen people, including Taylor, would be indicted in connection with Goebel's assassination. Three accepted immunity from prosecution in exchange for testimony. Only five ever went to trial, two of those being acquitted. Convictions were handed down against Taylor's Secretary of State Caleb Powers, Henry Youtsey, and Jim Howard. The prosecution charged that Powers was the mastermind, having a political opponent killed so that Taylor could stay in office. Youtsey was an alleged intermediary, and Howard, who was said to have been in Frankfort to seek a pardon from Taylor for the killing of a man in a family feud, was accused of being the actual assassin. Republican appeal courts overturned Powers' and Howard's convictions, though Powers was tried three more times, resulting in two convictions and a hung jury, and Howard was tried and convicted twice more. Both men were pardoned in 1908 by Willson.[51] Youtsey, who was sentenced to life imprisonment, did not appeal, but after two years in prison, he turned state's evidence. In Howard's second trial, Youtsey claimed that Taylor had discussed an assassination plot with Youtsey and Howard. He backed the prosecution's claims that Taylor and Powers worked out the details; he had acted as an intermediary, and Howard fired the shot. However, on cross-examination, the defense pointed out contradictions in the details of Youtsey's story, but Howard was still convicted. Youtsey was paroled in 1916 and was pardoned in 1919 by Democratic governor James D. Black.[51] Of those allegedly involved in the killing: Taylor died in 1928; Powers died in 1932; Youtsey died in 1942. Most historians agree that the identity of the assassin of Goebel is unclear.[6] Goebel Avenue in Elkton, Kentucky, and Goebel Park in Covington, Kentucky, are named in Goebel's honor.[51][52]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Either in Sullivan County[1][2] or Albany Township, Bradford County.[3]

- ↑ Equivalent to approximately $97,711,111 in 2020.

References

- 1 2 3 Harrison 2004, pp. 134–136.

- 1 2 3 Tapp & Klotter 1977, p. 412.

- 1 2 Heverly 1926, p. 469.

- ↑ Klotter 1977, p. 5.

- ↑ Klotter 1977, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Wall 2000.

- ↑ Klotter 1977, p. 7.

- ↑ Klotter 1977, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Klotter 1977, p. 9.

- 1 2 3 4 Klotter 1977, pp. 2–5.

- ↑ Klotter 1977, p. 16.

- ↑ Klotter 1977, p. 17.

- ↑ Klotter 1977, p. 10.

- ↑ Forum Press 1978, pp. 163–177.

- ↑ Klotter 1977, p. 24.

- ↑ Klotter 1977, p. 49.

- ↑ Klotter 1977, p. 26.

- ↑ Kentucky Legislative Research Commission 2003, pp. 15–18.

- ↑ Klotter 1977, p. 27.

- ↑ Forum Press 1978, pp. 166–167.

- ↑ Walker 2013.

- ↑ Klotter 1977, pp. 24–28.

- 1 2 Johnson 1916, pp. 272–279.

- ↑ Klotter 1977, p. 76.

- 1 2 Klotter 1977, pp. 34–35.

- 1 2 Johnson 1916, p. 273.

- ↑ Klotter 1977, pp. 36–39.

- ↑ Kentucky General Assembly 2005, pp. 234–235.

- ↑ Forum Press 1978, pp. 165–166.

- ↑ Klotter 1977, pp. 50–51.

- ↑ Forum Press 1978, pp. 164–165.

- ↑ Kleber 1992, p. 666.

- ↑ Tapp & Klotter 1977, p. 418.

- ↑ Kleber 1992, pp. 666–667.

- ↑ Kleber 1992, p. 667.

- ↑ Hughes, Schaefer & Williams 1900, pp. 46–47, 60.

- ↑ SAGE Publications 2009, p. 1616.

- ↑ Kleber 1992, p. 872.

- ↑ Johnson 1916, p. 302.

- ↑ Tapp & Klotter 1977, p. 443.

- 1 2 Harrison & Klotter 1997, pp. 271–272.

- ↑ Hughes, Schaefer & Williams 1900, pp. 233, 236.

- ↑ Hughes, Schaefer & Williams 1900, pp. 233, 235, 239.

- ↑ The Boston Post 1900.

- 1 2 Klotter 1977, pp. 108–109.

- ↑ Harkins 2015, p. 426.

- ↑ Klotter 1977, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ FindLaw.

- ↑ Klotter 1977, p. 114.

- ↑ Klotter 1977, pp. 114–116.

- 1 2 3 Johnson 1916, pp. 308–319.

- ↑ Simon 1996, p. 155.

Works cited

- "Taylor v. Beckham, 178 U.S. 548 (1900)". FindLaw. Retrieved November 27, 2021.

- Kentucky – Its History and Heritage. Forum Press. 1978. ISBN 978-0-88273-019-6.

- Harkins, Anthony (2015). "Colonels, Hillbillies, and Fightin': Twentieth-Century Kentucky in the National Imagination". The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society. Kentucky Historical Society. 113 (2): 421–452. doi:10.1353/khs.2015.0043. JSTOR 24641491. S2CID 161859779.

- Harrison, Lowell H., ed. (2004). "William Goebel". Kentucky's Governors (PDF). University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2326-4. Retrieved October 15, 2021 – via CORE.

- Harrison, Lowell H.; Klotter, James C. (1997). A New History of Kentucky. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2008-9.

- Heverly, Clement F. (1926). History and geography of Bradford County, Pennsylvania, 1615–1924. Bradford County Historical Society. OCLC 2843675.

- Hughes, Robert E.; Schaefer, Frederick W.; Williams, Eustace L. (1900). That Kentucky Campaign: Or, The law, The Ballot and The People in The Goebel–Taylor Contest. Robert Clarke & Company. OCLC 475793513. Retrieved November 27, 2021 – via Google Books.

- Johnson, Lewis F. (1916). Famous Kentucky Tragedies and Trials – A Collection of Important and Interesting Tragedies and Criminal Trials Which Have Taken Place in Kentucky. The Baldwin Law Book Company. OL 22879991M.

- "The Constitution of the United States of America and of the Commonwealth of Kentucky" (PDF). Kentucky General Assembly. October 2005. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- "Constitutional Background". Kentucky Government: Informational Bulletin No. 137 (Revised) (PDF). Kentucky Legislative Research Commission. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 17, 2017. Retrieved January 17, 2017 – via Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives.

- Kleber, John E. (1992). Clark, Thomas D.; Harrison, Lowell H.; Klotter, James C. (eds.). The Kentucky Encyclopedia. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-1772-0.

- Klotter, James C. (1977). William Goebel – The Politics of Wrath. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-3358-4.

- Guide to U.S. Elections. SAGE Publications. 2009. ISBN 978-1-60426-536-1.

- Simon, F. Kevin (1996). The WPA Guide to Kentucky. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-0865-0.

- Tapp, Hambleton; Klotter, James C. (1977). Kentucky: Decades of Discord, 1865–1900. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-916968-36-6.

- "Goebel No More". The Boston Globe. February 4, 1900. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- Walker, Marianne C (2013). "The Late Governor Goebel". Humanities. Vol. 34, no. 4. National Endowment for the Humanities. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

- Wall, Bennett H. (February 2000) [1999]. "Goebel, William (1856-1900), governor of Kentucky". American National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.0500280. ISBN 978-0-19-860669-7.

Further reading

- Clark, Thomas D. (1939). "The People, William Goebel, and the Kentucky Railroads". The Journal of Southern History. Southern Historical Association. 5 (1): 34–48. doi:10.2307/2191607. JSTOR 2191607.

.jpg.webp)