Winterhilfswerk des Deutschen Volkes | |

| Abbreviation | WHW |

|---|---|

| Formation | 1933 |

| Founded at | Berlin |

| Dissolved | May 9, 1945 |

| Type | Welfare organization |

| Location | |

Region served | Germany |

| Services | Food, clothing and fuel distribution |

| Leader | Erich Hilgenfeldt |

Parent organization | National Socialist People's Welfare |

| Funding | Public contributions |

The Winterhilfswerk des Deutschen Volkes (English: Winter Relief of the German People), commonly known by its abbreviated form Winterhilfswerk (WHW), was an annual donation drive by the National Socialist People's Welfare (German: Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt) to help finance charitable work. Initially an emergency measure to support people during the Great Depression, it went on to become a major source of funding for the activities of the NSV and a major component of Germany's welfare state. Donations to the WHW, which were voluntary in name but de facto required of German citizens, supplanted tax-funded welfare institutions and freed up money for rearmament.[1] Furthermore, it had the propagandistic role of publicly staging the solidarity of the Volksgemeinschaft.[2]

Background and early history

The Winterhilfswerk was organised by the National Socialist People's Welfare, a social welfare organisation whose declared purpose was "to develop and promote the living, healthy forces of the German people".[lower-alpha 1] The NSV's origins can be traced to Nazi party welfare activities during the Kampfzeit, when local groups were formed to provide aid to party members in distress. The Berlin association "Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt e.V." is considered the primary institutional ancestor of the NSV. Initially, the Berlin organisation was met with contempt by Nazi Party leaders: In 1932 the party informed the association's leadership that it had initiated legal proceedings because of "misuse of the word 'national socialist'".[3][lower-alpha 2] In 1933, the party changed its position; Hitler designated the NSV a party organ on 3 May 1933.[4] It went on to grow rapidly, counting 3.7 million members in 1934 and becoming the second largest mass organisation in Nazi Germany, behind the German Labour Front.[5] At the onset of the Second World War, it had more than 10 million members.[6]

Hitler ordered the establishment of the Winterhilfswerk in 1933 and personally opened the first drive, giving out the directive "no one shall be hungry, no one shall freeze".[lower-alpha 3] The initial donation drive in winter 1933/1934 took place against a backdrop of acute distress in large parts of the German populace; its initiation was partly a result of the party's desire to prevent social unrest.[7] The "Law on the Winterhilfswerk of the German People",[lower-alpha 4] passed on 1 December 1936, formally established the WHW as a registered association, to be led by the Reich Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda.[8]

Operation

The yearly donation drives by the Winterhilfswerk constituted the most visible part of the NSV's work.[9] As part of the centralisation of Nazi Germany, posters urged people to donate, rather than give directly to beggars.[10] The Hitlerjugend and Bund Deutscher Mädel (boys' and girls' associations, respectively) were extremely active in collecting for this charity. As part of the effort to place the community over the individual, totals were not reported for any individuals, only what the branch raised.[11]

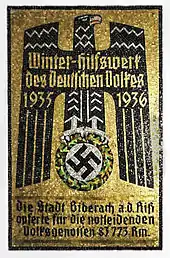

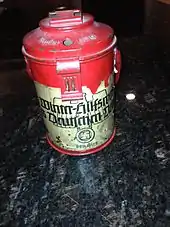

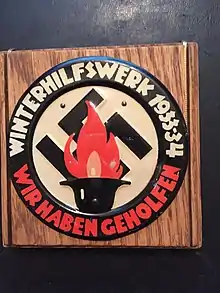

Certain weekends were assigned to all of the different Nazi associations, each with their own special Abzeichen, or badges, to pass out in exchange for a pfennig or two. The highly collectible items were made of many different materials, such as wood, glass, paper, terra cotta, metal and plastic. Over 8,000 different pieces had been produced by the end of the war, and some of the rarer ones sell for quite a lot of money today.

The Can Rattlers, as they became known, were relentless in their pursuit of making sure every good German citizen gave their share to the WHW. In fact, those who forgot to give had their names put in the paper to remind them of their neglect. Neighbors and even family members were encouraged to whisper the names of shirkers to their block leaders so that they could persuade them to do their duty. On one occasion, a civil servant was prosecuted for failure to donate, and his argument that it was voluntary was dismissed on the grounds it was an extreme view of liberty to neglect all duties that were not actually prescribed by law and therefore an abuse of liberty.[12] It was not unheard of for workers to lose their jobs for not donating to Winterhilfe or not giving enough. For instance, when a worker was fired for not donating to Winterhilfe, the firing was upheld by a labour court on the grounds that it was "conduct hostile to the community of the people [...] to be most strongly condemned".[13]

Large donations were also a means to establish oneself as a loyal supporter of the Nazi Party without the commitment of joining it.[14]

A greatly encouraged practice was once a month to have a one-pot meal (eintopf), reducing all the food to one course and the money thus saved was to be donated.[11] During autumn and winter months from 1933 onward, the Eintopfsonntag (One-Pot Sunday or Stew Sunday) was officially scheduled by the WHW. Restaurants were required to offer an eintopf meal at one of several price points. Households were reminded of the occasion, although it has been noted that the authorities did not investigate whether the one-pot meal was actually served.[15]

Collection drives were a mainstay of the Winter Relief and those who did not give, or gave little (such as one pair of boots to a clothing drive), were sometimes the victims of mob violence and needed to be protected by the police, [16] known in French as the Secours d'Hiver in Belgium.[17]

Gifts and tokens

A paper Monatstürplakette (monthly placard) was issued to place on one's door or in one's window to show others that one had given and also to keep the roaming bands of charity workers at bay.[18]

Donors were often given small souvenir gratitude gifts of negligible value, somewhat similar to the way modern charities mail out address labels and holiday cards. A typical such gift was a very small propaganda booklet,[19] reminiscent of Victorian-era miniature books; about 0.8" wide x 1.5" tall. Booklets included The Führer Makes History,[20][19] a collection of Hitler photographs,[21] and Gerhard Koeppen and other decorated heroes of the war.[22]

More generous donors would receive concomitantly better gifts, such as lapel pins on a wide variety of themes. Some depicting occupational types or geographic areas of the Reich, others animals, birds and insects, nursery rhyme and fairy tale characters, or notable persons from German history (including Hitler himself). They were made from a variety of materials. Each individual miniature book, badge, badge set or toy set was only available for two or three days of a particular collection drive. The populace would be encouraged to donate the following week and thereby collect the latest in the series. There could also be consequences such as nagging by the appropriate official if your local Blockleiter saw that you were not wearing the current, appropriate pin by about Tuesday of the week.

When he visited Germany in 1939 as a reporter for the North American Newspaper Alliance, Lothrop Stoddard wrote[23]

Once a fortnight, every city, town, and village in the Reich seethes with brown-shirted Storm Troopers carrying red-painted canisters. These are the Winter-Help collection-boxes. The Brown-Shirts go everywhere. You cannot sit in a restaurant or beer-hall but what, sooner or later, a pair of them will work through the place, rattling their canisters ostentatiously in the faces of customers. And I never saw a German formally refuse to drop in his mite, even though the contribution might have been less than the equivalent of one American cent.

During these periodic money-raising campaigns, all sorts of dodges are employed. On busy street-corners comedians, singers, musicians, sailors, gather a crowd by some amusing skit, at the close of which the Brown-Shirts collect. People buy tiny badges to show they have contributed—badges good only for that particular campaign. One time they may be an artificial flower; next time a miniature dagger, and so forth. The Winter-Help campaign series reaches its climax shortly before Christmas in the so-called Day of National Solidarity. On that notable occasion the Big Guns of the Nazi Party sally forth with their collection-boxes to do their bit.

The 1933–1945 collection drives issued a large number of themed ceramic medallions and other badges given to donators.[lower-alpha 5]

Use of Funds

A 1938 Nazi propaganda leaflet claimed that the Winterhilfswerk had collected nearly a billion Reichsmarks from 1933 to 1937 as well as half a billion in goods and two million kilograms of coal.[24]

However, in 1937 a group of exiled German economists writing under the pseudonym 'Germanicus' produced figures comparing the Winterhilfswerk of 1933 with the pre-existing Reich Winter Help of 1931. The figures showed that the Winterhilfswerk provided slightly more coal and potatoes to the needy, but dramatically less bread and meat. They also pointed out that the Reich Winter Help was supplemented by the relief efforts of the states and private organisations, but this help had ceased under the Nazis.[25]

American racialist author Lothrop Stoddard, who visited Nazi Germany in 1939, described visits to a Winterhilfswerk facility where he was shown winter clothing and other items meant for distribution.[23] Others describe the charitable aims of the Winterhilfswerk and details on the collection of money and goods, but little about what was done with either.

American diplomat William Russell's eyewitness book Berlin Embassy pointed out that no account was ever made of where the huge amounts raised by Winterhilfswerk were spent. His contention was not only that the program was a sham and that all the proceeds were used to produce armaments, but that the entire German population knew this to be the case.[26] Similarly, the Gestapo reported persistent rumours that Winterhilfswerk funds were used for Nazi party and military purposes.[27]

Further, in 1936, Nazi Party treasurer Franz Xaver Schwarz commented to Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess "It has repeatedly become necessary for the Führer to use WHW funds for other purposes." In 1941, after complaining that large amounts of WHW and NSV funds were being siphoned off without his agreement, Schwarz was told by the Chief of the Party Chancellery, Martin Bormann, that Adolf Hitler alone controlled and allocated the money.[27]

Notes

- ↑ "die lebendigen, gesunden Kräfte des deutschen Volkes zu entfalten und zu fördern". Störmer, Hellmuth: Das rechtliche Verhältnis der NS-Volkswohlfahrt und des Winterhilfswerkes zu den Betreuten im Vergleiche zur öffentlichen Wohlfahrtspflege, 1940, p. 52f. Quoted in Vorländer 1988, p. 329

- ↑ "gegen den Mißbrauch des Wortes 'nationalsozialistisch' durch die Vereinsführung die nötigen rechtlichen Maßnahmen eingeleitet". Quoted in Vorländer 1986, pp. 345–346

- ↑ "keiner soll hungern, keiner soll frieren". Quoted in Vorländer 1988, p. 46

- ↑ "Gesetz über das Winterhilfswerk des Deutschen Volkes"

- ↑ Collections:

- Rainer Baumann (1973). WHW Abzeichen der Reichsstrassen-Sammlung 1933-1944.

- Harry Rosenberg (1974). Spenden-Abzeichen des WHW.

- Gerhard Janaczek (1982). WHW Abzeichen Strassensammlungen.

- Holger Rosenberg (1983). Spendenbelege des WHW und KWHW 1933-1945: Überregionale.

- Holger Rosenberg (1987). Spendenbelege des WHW und KWHW 1933-1945: Gausammlungen Gau 1-Gau 10.

- Reinhard Tieste (1990). Spendenbelege des WHW und KWHW 1933-1945: Gausammlungen Gau 11-Gau 20.

- Reinhard Tieste (1993). Spendenbelege des WHW, Band IV: Gausammlungen 1933-1945 Gaue 21-30.

- Reinhard Tieste (1993). Spendenbelege des WHW, Band V: Gausammlungen 1933-1945 Gaue 31-40.

References

- ↑ Kramer 2017, p. 144; Evans 2005.

- ↑ Scriba 2015.

- ↑ Schoen 1986, p. 200.

- ↑ Vorländer 1988, p. 4; Vorländer 1986, p. 342.

- ↑ Schoen 1986, p. 199.

- ↑ Vorländer 1986, p. 342.

- ↑ Vorländer 1988, p. 45-46.

- ↑ Vorländer 1986, p. 368.

- ↑ Kramer 2017, p. 144.

- ↑ Koonz 2003.

- 1 2 Grunberger 1971, p. 79.

- ↑ Mazower 1999, p. 36.

- ↑ Shirer 1990.

- ↑ Mayer 1995, p. 90.

- ↑ Bytwerk 2004.

- ↑ Grunberger 1971, p. 79-80.

- ↑ ABE 2015.

- ↑ Grunberger 1971, p. 80.

- 1 2 Bytwerk 1998a.

- ↑ Bytwerk 1999a.

- ↑ Bytwerk 1998b.

- ↑ Bytwerk 1999b.

- 1 2 Stoddard 1940.

- ↑ Bytwerk 1998c.

- ↑ Germanicus 1937, p. 76.

- ↑ Russell 1941, p. 207.

- 1 2 de Witt 1978, p. 270.

Bibliography

- "Seconde Guerre mondiale: Les archives du Secours d'Hiver ouvertes à la recherche - Archives de l'État en Belgique". www.arch.be. Archives de l'État en Belgique. 14 September 2015. Retrieved 2021-02-10.

- Bytwerk, Randall (ed.). "Winterhilfswerk Booklet for 1933". German Propaganda Archives. Calvin University. Retrieved 2021-02-10.

- Bytwerk, Randall (ed.). "Winterhilfswerk Booklet for 1938". German Propaganda Archives. Calvin University. Retrieved 2021-02-10.

- Bytwerk, Randall (ed.). "Gerhard Koeppen". German Propaganda Archives. Calvin University. Retrieved 2021-02-10.

- Bytwerk, Randall (ed.). "Hitler in the Mountains". German Propaganda Archives. Calvin University. Retrieved 2021-02-10.

- Bytwerk, Randall (ed.). "We Owe It to the Führer". German Propaganda Archives. Calvin University. Retrieved 2023-03-12.

- Bytwerk, Randall L. (2004). Bending Spines: The Propagandas of Nazi Germany and the German Democratic Republic. East Lansing, Michigan: Michigan State University Press. ISBN 9780870137105.

- Evans, Richard J. (2005). The Third Reich in power, 1933-1939. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 1-59420-074-2. OCLC 61451667.

- Germanicus (pseud) (1937). Germany, The Last Four Years. Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin.

- Grunberger, Richard (1971). The 12-year Reich: A social history of Nazi Germany, 1933-1945 (1 ed.). New York. ISBN 0-03-076435-1. OCLC 161622.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Koonz, Claudia (2003). The Nazi conscience. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press. ISBN 0-674-01172-4. OCLC 52216250.

- Kramer, Nicole (2017). Raphael, Lutz (ed.). Poverty and Welfare in Modern German History. Vol. 7 (1 ed.). Berghahn Books. doi:10.2307/j.ctvss40nq.10. ISBN 978-1-78920-515-2.

- Mazower (1999). Dark continent: Europe's twentieth century. New York: A.A. Knopf. ISBN 0-679-43809-2. OCLC 38580276.

- Mayer, Milton (1995). They thought they were free: The Germans, 1933-45. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-52583-9. OCLC 980231546. - Worldcat link

- Russell, William (1941). Berlin Embassy. New York: EP Dutton and Company.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Schoen, Paul (1986). "Geschichte, Selbstanspruch und Stellenwert der Nationalsozialistischen Volkswohlfahrt e.V. (NSV) 1933-1939". In Otto, Hans-Uwe; Sünker, Heinz (eds.). Soziale Arbeit und Faschismus (1 ed.). Bielefeld. pp. 199–220. ISBN 978-3-925515-01-9. OCLC 220599671.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Scriba, Arnulf (16 September 2015). "Das Winterhilfswerk (WHW)". www.dhm.de (in German). Deutsches Historisches Museum. Retrieved 2021-02-10.

- Shirer, William Lawrence (1990). The rise and fall of the Third Reich: A history of Nazi Germany. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-72869-5. OCLC 22888118.

- Stoddard, Lothrop (1940). Into the Darkness. Salt Lake City, Utah: Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- Vorländer, Herwart (1986). "NS-Volkswohlfahrt und Winterhilfswerk des deutschen Volkes". Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte. 34 (3): 341–380. ISSN 0042-5702. JSTOR 30195299.

- Vorländer, Herwart (1988). Die NSV: Darstellung und Dokumentation einer nationalsozialistischen Organisation. Boppard am Rhein: H. Boldt. ISBN 3-7646-1874-4. OCLC 18128757.

- de Witt, Thomas (September 1978). "The Economics and Politics of Welfare in the Third Reich". Central European History. 11 (3): 256–278. doi:10.1017/S0008938900018719. JSTOR 4545836. S2CID 154446465. Retrieved 3 Dec 2023.