| Tomb of Wirkak | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) The tomb of Wirkak (roof reconstructed), Xi'an City Museum.[1] | |

| Created | 580 CE |

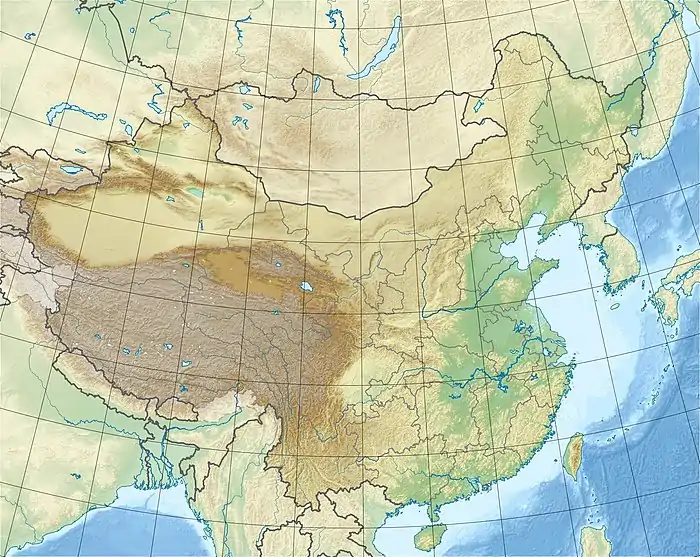

.png.webp) Xi'an  Xi'an | |

| Sogdian tombs in China | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||

The Tomb of Wirkak (Sogdian: wyrkʾk), in Chinese commonly referred to as Tomb of Master Shi (Chinese: 史君墓; pinyin: Shǐ Jūn Mù; Wade–Giles: Shih3-Chün1 Mu4), is the grave of the Sogdian Sabao (Chinese: 薩保, "Protector, Guardian", derived from the Sogdian word s’rtp’w, "caravan leader") Wirkak and his wife Wiyusi, dating from 580 AD (Northern Zhou dynasty). The tomb was discovered in 2003 in the east of Jingshang village in Daminggong township, Weiyang District, Xi'an, and excavated between June and October in the same year.[2] It is especially significant for the rich content of the reliefs on the stone structure contained in the tomb and a bilingual epitaph.[3] Sogdian tombs in China are among the most lavish of the period in this country, and are only slightly inferior to Imperial tombs, suggesting that the Sogdian Sabao were among the wealthiest members of the population.[4]

Tomb occupants

The bilingual epitaph written in Classical Chinese and Sogdian language sheds light on the life of an 86-year-old man named Wirkak (493–579 AD) in Sogdian, but Shi Jun (史君) in Chinese, and his wife Wiyusi. The Sogdian name Wirkak is derived from the word for "wolf".[5] The Chinese name Shi Jun is composed of the surname Shi (史) with the honorific jun (君) or "master"; the space for his Chinese given name was left blank, so it is unknown. The name of his wife, Wiyusi, means "dawn" in Sogdian.[6] The couple came from the State of Shi and the State of Kang (Samarkand origin) respectively. In his lifetime, Wirkak served as a sabao in the ancient province of Liangzhou, or today's city of Wuwei, a once-booming hub of international trade on the Silk Road. Sabao (薩保) is a Chinese translation of the Sogdian term s′rtp′w, meaning a "caravan leader", but later became the title of an administrator in charge of the international and foreign religious affairs of Central Asian immigrants who settled in China at the time.

According to the epitaph, Wirkak had lived in the Western Regions but had moved to Chang'an. His grandfather, Rštßntk (阿史盤陁, Ashipantuo), had been a sabao in his native land. His father was named Wn’wk (阿奴伽, Anujia), but no office is listed for him. Wirkak was appointed as chief of the judicial department of the sabao bureau in the Datong reign (535–546) during the Liang dynasty, then in the 5th year of the same reign (539), he was made sabao of Liangzhou. He died in 579 at the age of 86; his wife Wiyusi died a month later. The tomb was built by their three sons, and the interment took place one year later in 580.

Tomb

The total length of the tomb was 47.26 metres, with long slope path and yard faces south with an azimuth of 186º. It consists of ramp, yard, tunnel, a corridor and a chamber. The number of the yards and the tunnels are both five. The corridor measures 2.8 m long, 1.5 m wide and 1.9 m high with an arch ceiling. The chamber has a rectangular plan, it is 3.7 m long from the east to the west and 3.5 m from the north to the south.

There are two sealed gates of bricks and stones between the ramp and the chamber. The lintel and side posts of the stone gate are carved with interlocking grape and acanthus patterns, celestial musicians and lokapalas. Mural paintings can be seen in the ramping passageway and the chamber, however, the subjects are undistinguishable owing to the poor condition. A sarcophagus was found in the mid-north of the chamber.

The tomb had been robbed, from what remained, archaeologists identified a gold earring, a gold ring and a gold coin which is an imitation of Byzantine coins.[9][10]

Sarcophagus

.jpg.webp)

The sarcophagus measures 2.46 m in length, 1.55 m in width and 1.58 m in height, shaped like a timber-framed Chinese house or temple with a hip-and-gable roof, made of originally painted and gilded stone slabs, and is formed of a base, middle wall slabs and a top. According to the American art historian Wu Hung, house-shaped sarcophagus originated in the western province of Sichuan during the Han period (202 BC – 220 AD), and this type of sarcophagus symbolizes some sort of ethnic connection, since it was not used by the indigenous Chinese who had lived in central and southern China, but was preferred by the Xianbei, Sogdian, and other people of Chinese or non-Chinese ancestry who had immigrated to northern China from the West.[11]

Wirkak's sarcophagus is densely decorated with bas-reliefs to convey blind architectural details and a complex figural programme.[12] The four sides are carved with four-armed guardian deities, along with other Zoroastrian divinities and scenes of sacrifice, rising to heaven, banqueting, hunting and procession. Their subjects and style demonstrate features of the Western Regions (Central Asia). The French historian Étienne de La Vaissière argues that the iconography of these bas-reliefs representing a religious syncretism by blending Manichaean and Zoroastrian symbols in the funerary art.[13] Despite the fact that the sarcophagus has adopted a unique style to creating a miniature model of a traditional Chinese temple, the sinicisation of Wirkak's tomb is of the lowest degree among the other two Sogdian tombs: those of Kang Ye and An Jia.[14]

Epigraphy

Sogdian and Chinese epitaph

The epitaph reads:

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

(The period) Daxiang of Great Zhou, year 2, in the first month of a rat year, on the 23rd day. So: there was a man of a family from Kish, domiciled in Guzang. From the emperor he holds the rank (of) sabao of Guzang, in the land of the Sogdians, a landowner. He is named Wirkakk, the son of Wanuk, (namely) Wanuk, the son of the sabao. And (his) wife, born in Xinping, is named Wiyusi. And Wirkakk the sabao married (his) wife in Xinping in a pig year, on the 7th day of the 6th month, on a hare day. And afterwards, here in Xianyang (= Chang’an), he himself died in a pig year, on the 7th day of the 5th month. And his wife too died on the 7th day of the 6th month, on a hare day, in the same year (as her) marriage, the same month, the same day. There is no living being which is born which is not subject to death; moreover, it is hard to complete (one’s) period in the world of the living. But this is harder (still), that, without being aware (of it), a husband and wife see one another (for the first time) the same year, the same month, the same day, in the human world (and) also in paradise, (so that) the beginning of (their) life together (in each place) may be at the same period. This stone tomb was made by Vreshman-vande, Zhimat-vande (and) Prot-vande, desiring a suitable place for (their) father (and) mother.

Front

The front (South) side of the sarcophagus is organised in strict formal symmetry around a large two-winged door. The Sogdian and Chinese inscriptions of the tomb occupants' career are manifested above the door. Flanking the door is a pair of inner panels with a guardian deity in each, and an additional pair of outer panels that feature three sections. From top to bottom, each outer panel contains a group of Sogdian musicians, a stylised window flanked by a pair of foreigners, and a half-human half-bird priest standing before the holy fire in a portable brazier.

Sides

The six biographical panels (Panels "a–f", Nos. 2–7) start on the middle panel of the left side and conclude on the last-but-one panel of the back. They are preceded and followed by two single religious panels (Nos. 1 and 8), which continue with three additional religious panels (Nos. 9–11) on the right (East) side.[12] The description of the six biographical panels as stated by Albert E. Dien:[16]

- Panel "a" (No. 2): the young Wirkak and his father came by horse to call on a couple wearing crowns that indicate they are regal.

- Panel "b" (No. 3): the ruler hunts as a caravan moves at the bottom of the panel.

- Panel "c" (No. 4): the caravan now rests by a river as the Sogdians, presumably still Wirkak and his father, visit yet another ruler sitting in his yurt.

- Panel "d" (No. 5): the regal couple have a grand reception, with music and dance.

- Panel "e" (No. 6): the grown Wirkak rides with his wife, both shielded by umbrellas.

- Panel "f" (No. 7): in this panel depicts a party, with five men at the top, sitting on a carpet, and exchanging toasts. Musicians and servants with large dishes of food surround them. Below, five women also sit on a rug and drink.

The description of the five religious panels as stated by Zsuzsanna Gulácsi:[12]

- Panel No. 1 Divine Being Giving a Sermon: it constitutes a scene that organises nine figures in a clear visual hierarchy: one main figure appears as a sermonising deity, interacting with two laypeople flanked by two groups of three seated figures. Prominently placed in front of the deity at the lower left is a lay couple (referencing Wirkak and Wiyusi), sitting on their heels while assuming gestures of homage and prayer with their hands clasped.

- Panel No. 8 Sage in a Cave and Angelic Rescue: the motif of a sage in a cave occupies the upper third of the carving, the scene is set in a forested mountainous landscape framed by flowering trees. The body of the sage is seated casually with legs crossed and gesturing with right hand to a small four-legged animal that looks like a monkey. Below shows some winged apsaras or angelic beings flying above the water, with a man and a woman (possibly symbolising Wirkak and Wiyusi).

- Panel No. 9 Admittance to Paradise: on the upper half of this panel shows a couple (symbolising the souls of Wirkak and Wiyusi after death) greeted by Weshparkar—the Sogdian god of the Atmosphere—as travellers who have just arrived, seated on their heels holding a footed plate and a drinking cup, respectively. The lower half depicts the Chinvat Bridge.

- Panel No. 10 A Winged Figure, a Falling Figure, and a Pair of Winged Horses: in the upper right, a winged figure, carrying a small object in the left hand, is shown flying ahead of a pair of winged horses. Directly below, is a unique falling figure, dressed in a long robe with hair piled up into a topknot, pointedly portrayed facing away from the viewer. The lower half portrays the extended scene of Chinvat Bridge of the previous panel.

- Panel No. 11: the final panel shows a number of winged figures flying in a direction opposite to that of the Panel No. 10, that is, towards the left. The riders—a man and a woman—representing the souls of Wirkak and Wiyusi. The context of their ride, surrounded by heavenly musicians, references their entrance into Garōdmān, the "House of Song" Paradise of Zoroastrianism.[12]

Ethnographical aspects

The Hephthalites are omnipresent in the depictions on the Tomb of Wirkak, as royal figures with elaborate Sasanian-type crowns appearing in their palaces, nomadic yurts or hunting in panels 2 to 5: Wirkak may therefore have primarily dealt with the Hephthalites during his younger years (he was around 60 when the Hephthalites were finally destroyed by the alliance of the Sasanians and the Turks of the First Turkic Khaganate between 556 and 560 CE).[17] On the contrary, the depictions in the Tomb of An Jia (who was 24 years younger than Wirwak) show the omnipresence of the Turks, who were probably his main trading partners during his active life.[17] On the tomb of An Jia, the Hephthalites are essentially absent, or possibly showed once as a vassal ruler outside of the yurt of the Turk Qaghan.[17][18]

Parallels

The tomb of Wirkak is comparable to the tomb of Li Jingxun (Chinese: 李静训, 600-608 CE) a Sui dynasty princess with foreign ethnic affiliation, whose stone sarcophagus was found near Liangjiazhuang in Xi'an, Shaanxi Province, China.[19] Her lavish tomb contained many artifacts from the Silk Road, and foreign-style objects.[19][20] The tomb included gold cups, jades, porcelains and toys, as well as a coin of the Sasanian Emperor Peroz I (459-483 CE).[20] It is thought that the tomb artifacts reflect her northern ethnic background.[19] Such stone sarcophagy are related to the tradition of Sogdian tombs in China, such as the tomb of Wirkak.[19]

Gallery

.jpg.webp)

Line drawing copy of the left (West) side of Wirkak's sarcophagus.

Line drawing copy of the left (West) side of Wirkak's sarcophagus. Line drawing copy of the right (East) side of Wirkak's sarcophagus.

Line drawing copy of the right (East) side of Wirkak's sarcophagus. Chinvat Bridge scene, right side.

Chinvat Bridge scene, right side.

See also

External links

- Tan, Panpan (2020). "Technological characterization of gold jewellery from the Sogdian tomb of Shi Jun (d. 579 CE) in Xi'an, Shaanxi Province" (PDF). Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 10804. Bibcode:2020NatSR..1010804T. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-67788-8. PMC 7330028. PMID 32612241. S2CID 220292014.

References

- ↑ Li, Yusheng (2016). "STUDY OF TOMBS OF HU PEOPLE IN LATE 6TH CENTURY NORTHERN CHINA". Newsletter di Archeologia. 7: 125, Fig.17.

- ↑ "Ancient Tombs of Laowai Found". china.org.cn. 2005. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ↑ Dien, Albert E. (2003). "Observations Concerning the Tomb of Master Shi". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 17: 105–115. JSTOR 24049308.

- ↑ GRENET, Frantz (2020). Histoire et cultures de l'Asie centrale préislamique. Paris, France: Collège de France. p. 320. ISBN 978-2-7226-0516-9.

Ce sont les décors funéraires les plus riches de cette époque, venant juste après ceux de la famille impériale; il est probable que les sabao étaient parmi les éléments les plus fortunés de la population.

- ↑ Hansen, Valerie (2015). The Silk Road: A New History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 145. ISBN 9780190218423.

- ↑ Hsieh, Chin-yü (27 February 2015). "【絲路控】狼男與黎明少女:六世紀粟特移民的婚姻" [Wolf Man and Maiden of Dawn: A Marriage of the 6th-Century Sogdian Immigrants]. storystudio.tw (in Chinese (Taiwan)). Retrieved 4 December 2018.

她叫維優斯 (Wiyusī),意思是「黎明」.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tan, Panpan; Yang, Junchang; Liu, Yan; Zheng, Yaozheng; Yang, Junkai (1 July 2020). "Technological characterization of gold jewellery from the Sogdian tomb of Shi Jun (d. 579 CE) in Xi'an, Shaanxi Province". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 10804. Bibcode:2020NatSR..1010804T. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-67788-8. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 7330028. PMID 32612241.

- ↑ "Shi Jun's Sarcophagus (photographs)". sogdians.si.edu.

- ↑ Guo, Yunyan (9 July 2018). "關於西安北周史君墓出土金幣仿製品的一點補充". nxkg.org.cn (in Simplified Chinese). Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ↑ "Shi Jun Tomb of the Northern Zhou Dynasty". kaogu.cn. 2014. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ↑ Huang, Bing (2021). "Deciphering the Shi Jun Sarcophagus Using Sogdian Religious Beliefs, Tales, and Hymns". Religions. 12 (12): 1060. doi:10.3390/rel12121060.

- 1 2 3 4 Gulácsi, Zsuzsanna (2012–2016). "The Religion of Wirkak and Wiyusi: The Zoroastrian Iconographic Program on a Sogdian Sarcophagus from Sixth-Century Xi'an". academia.edu. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ↑ De La Vaissière, Étienne (2015). "Wirkak: Manichaean, Zoroastrian, Khurramî?". academia.edu. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ↑ Wu, Tʻien-tʻai, ed. (2015). 族群與社會 [Ethnicity and Society] (in Chinese (Taiwan)). Taipei: Wu-Nan Book. p. 290. ISBN 9789571141756. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ↑ Sims-Williams, Nicholas (October 2021). "The Sogdian epitaph of Shi Jun and his wife". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 84 (3): 505–513. doi:10.1017/S0041977X21000732.

- ↑ Dien, Albert E. (2009). "The Tomb of the Sogdian Master Shi: Insights into the Life of a Sabao" (PDF). edspace.american.edu. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- 1 2 3 Grenet, Frantz; Riboud, Pénélope (2003). "A Reflection of the Hephthalite Empire: The Biographical Narra- tive in the Reliefs of the Tomb of the Sabao Wirkak (494-579)" (PDF). Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 17: 141–142.

- ↑ GRENET, Frantz (2020). Histoire et cultures de l'Asie centrale préislamique. Paris, France: Collège de France. p. 326. ISBN 978-2-7226-0516-9.

- 1 2 3 4 Wu, Mandy Jui-man (2004). "Exotic Goods as Mortuary Display in Sui Dynasty Tombs--A Case Study of Li Jingxun's Tomb". Sino-Platonic Papers. 142.

- 1 2 XIONG, VICTOR CUNRUI; LAING, ELLEN JOHNSTON (1991). "Foreign Jewelry in Ancient China". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 5: 163–173. ISSN 0890-4464. JSTOR 24048294.

- ↑ Li, Yusheng (2016). "STUDY OF TOMBS OF HU PEOPLE IN LATE 6TH CENTURY NORTHERN CHINA". Newsletter di Archeologia. 7: 115, Fig.2.

Further reading

- Sims-Williams, N. (2021). "The Sogdian epitaph of Shi Jun and his wife". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 84 (3): 505–513. doi:10.1017/S0041977X21000732. S2CID 245438980.

External links

- "Shi Jun's Sarcophagus The Sogdians". sogdians.si.edu.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)