Wolf teeth are small, peg-like horse teeth, which sit just in front of (or rostral to) the first cheek teeth of horses and other equids. They are vestigial first premolars, and the first cheek tooth is referred to as the second premolar even when wolf teeth are not present. Torbjörn Lundström in Sweden reported that about 45-50% of 25000 horses had wolf teeth. They are much less common in the mandible (lower jaw) than the maxilla (upper jaw) although mandibular wolf teeth are found very occasionally.

They do not have any deciduous precursors, but they may themselves be deciduous, as it is believed that they are often shed when the deciduous 2nd premolar is shed at around two and a half years of age. They may also be knocked out by the bit if particularly loose, and can certainly be extracted accidentally, either partially or whole, when routine equine dentistry is performed.

In size they are extremely variable from being small pegs only 3 mm in diameter to having roots up to 2 cm long. In a small number of cases they may be "molarized" with a distinct irregular rim of enamel. It is impossible to gauge the size of the root from an examination of the crown, except to say that if the crown is mobile it is very unlikely that there is a large intact root.

There is dispute as to the average time of eruption with different authors suggesting different times. All authors who have performed any type of rigorous study suggest that they erupt between birth and 18 months although most say 6–9 months.

Where there are two wolf teeth next to each other, it is very likely that one is a fragment of the deciduous 2nd premolar.

Blind wolf teeth

Blind wolf teeth are wolf teeth that are present but may not have erupted through the gum. They may remain completely underneath the gingiva. A good rule that holds true in most cases is:

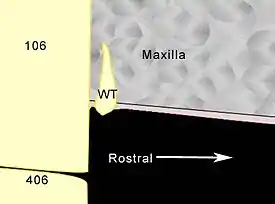

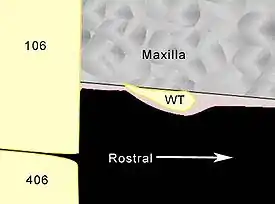

- The further forward or rostral a wolf tooth is, the more likely it is that the wolf tooth will be blind and the more likely that the root will lie more parallel with the maxilla rather than perpendicular to the line of the maxilla.

This is shown in the diagrams below where 106 and 406 are the second premolars according to the Modified triadan system and WT is the wolf tooth. The pink layer is the gum.

How wolf teeth might cause problems

Normal wolf teeth without pathology are not inherently painful to a horse which does not have a bit in its mouth. Equally certain is that there are cases where wolf teeth do cause significant problems to horses because of their interaction with the bit.

There are four mechanisms which have been postulated by which wolf teeth may cause discomfort. It is probable that all four of these mechanisms are possible in different cases.

- The wolf tooth and/or periodontium is inherently painful

- Only likely where the tooth is pathological or very loose

- Unlikely to be true for healthy wolf teeth

- The bit pushes the cheek towards a sharp/large wolf tooth causing cheek pain

- Certainly a viable mechanism where the wolf tooth is large and positioned so that it has close contact with the buccal mucosa

- The bit touching a wolf tooth causes pain or discomfort in wolf tooth

- Possible if bit is being pushed towards tooth with force or tooth is inherently sensitive to pressure or contact with bit

- A wolf tooth physically restricts the movement of the bit

- Only with very large or rostrally positioned wolf teeth

Assessing which wolf teeth should be removed

There is a school of thought which says that all ridden horses' wolf teeth should be extracted, because if they are removed then they cannot cause problems, and it is not a major surgical procedure. With the wolf teeth removed, it is also easier to put in a proper bit seat. There is another school of thought which believes that wolf teeth should be assessed and removed when they are likely to be causing a problem. Very few vets or equine dental technicians subscribe to the belief that they are never a problem. Certainly it is useful to assess wolf teeth because some horse owners are reluctant to have them removed unless they are very likely to be causing problems.

The following factors are useful in making an assessment:

- Position

- A rostrally-positioned wolf tooth is more likely to touch the bit or to pinch buccal mucosa pushed towards it by the bit. A wolf tooth tucked in on the inside of the 2nd premolar is much less likely to cause problems.

- Size

- A large wolf tooth is more likely to interfere, although a small one may be such a small job to take out that it is better to just remove it.

- Movement

- Any wolf tooth which moves is likely to be small, a fragment, or be a fractured crown. All three are probably better removed.

- Damage

- Any damaged wolf tooth is more likely to be inherently painful or have periodontal disease associated with it.

- Asymmetry

- Common sense suggests that, where a horse only has one wolf tooth, it is less likely to have a uniform response to the bit on both reins.

- Whether they are blind

- Many veterinarians and equine dental technicians believe that blind wolf teeth are more likely to be problematic.

- Whether they are maxillary or mandibular

- It is without dispute that mandibular wolf teeth are more likely to cause interference than maxillary wolf teeth, because the bit is drawn towards the mandible with most bit/bridle arrangements.

- The intended use of the horse

- Where a horse is performing at a high level it is less acceptable to have any doubt in relation to possible problems caused by wolf teeth.

- The age of the horse

- Where wolf teeth are discovered in an elderly horse, there are strong arguments for maintaining a status quo.

- How the horse is performing

- Most authorities would agree that any horse with wolf teeth that is not responding well to the bit should have them removed.