Milling cutters are cutting tools typically used in milling machines or machining centres to perform milling operations (and occasionally in other machine tools). They remove material by their movement within the machine (e.g., a ball nose mill) or directly from the cutter's shape (e.g., a form tool such as a hobbing cutter).

Features of a milling cutter

Milling cutters come in several shapes and many sizes. There is also a choice of coatings, as well as rake angle and number of cutting surfaces.

- Shape: Several standard shapes of milling cutters are used in industry today, which are explained in more detail below.

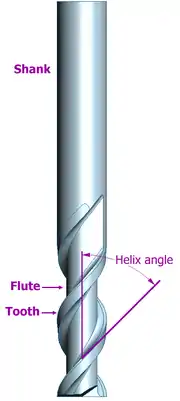

- Flutes / teeth: The flutes of the milling bit are the deep helical grooves running up the cutter, while the sharp blade along the edge of the flute is known as the tooth. The tooth cuts the material, and chips of this material are pulled up the flute by the rotation of the cutter. There is almost always one tooth per flute, but some cutters have two teeth per flute.[1] Often, the words flute and tooth are used interchangeably. Milling cutters may have from one to many teeth, with two, three and four being most common. Typically, the more teeth a cutter has, the more rapidly it can remove material. So, a 4-tooth cutter can remove material at twice the rate of a two-tooth cutter.

- Helix angle: The flutes of a milling cutter are almost always helical. If the flutes were straight, the whole tooth would impact the material at once, causing vibration and reducing accuracy and surface quality. Setting the flutes at an angle allows the tooth to enter the material gradually, reducing vibration. Typically, finishing cutters have a higher rake angle (tighter helix) to give a better finish.

- Center cutting: Some milling cutters can drill straight down (plunge) through the material, while others cannot. This is because the teeth of some cutters do not go all the way to the centre of the end face. However, these cutters can cut downwards at an angle of 45 degrees or so.

- Roughing or Finishing: Different types of cutter are available for cutting away large amounts of material, leaving a poor surface finish (roughing), or removing a smaller amount of material, but leaving a good surface finish (finishing). A roughing cutter may have serrated teeth for breaking the chips of material into smaller pieces. These teeth leave a rough surface behind. A finishing cutter may have a large number (four or more) teeth for removing material carefully. However, the large number of flutes leaves little room for efficient swarf removal, so they are less appropriate for removing large amounts of material.

- Coatings: The right tool coatings can have a great influence on the cutting process by increasing cutting speed and tool life, and improving the surface finish. Polycrystalline diamond (PCD) is an exceptionally hard coating used on cutters that must withstand high abrasive wear. A PCD coated tool may last up to 100 times longer than an uncoated tool. However, the coating cannot be used at temperatures above 600 degrees C, or on ferrous metals. Tools for machining aluminium are sometimes given a coating of TiAlN. Aluminium is a relatively sticky metal, and can weld itself to the teeth of tools, causing them to appear blunt. However, it tends not to stick to TiAlN, allowing the tool to be used for much longer in aluminium.

- Shank: The shank is the cylindrical (non-fluted) part of the tool which is used to hold and locate it in the tool holder. A shank may be perfectly round, and held by friction, or it may have a Weldon Flat, where a set screw, also known as a grub screw, makes contact for increased torque without the tool slipping. The diameter may be different from the diameter of the cutting part of the tool, so that it can be held by a standard tool holder.§ The length of the shank might also be available in different sizes, with relatively short shanks (about 1.5x diameter) called "stub", long (5x diameter), extra long (8x diameter) and extra extra long (12x diameter).

Types

End mill

End mills (middle row in image) are those tools that have cutting teeth at one end, as well as on the sides. The words end mill are generally used to refer to flat bottomed cutters, but also include rounded cutters (referred to as ball nosed) and radiused cutters (referred to as bull nose, or torus). They are usually made from high speed steel or cemented carbide, and have one or more flutes. They are the most common tool used in a vertical mill.

Roughing end mill

Roughing end mills quickly remove large amounts of material. This kind of end mill utilizes a wavy tooth form cut on the periphery. These wavy teeth act as many successive cutting edges producing many small chips. This results in a relatively rough surface finish, but the swarf takes the form of short thin sections and is more manageable than a thicker more ribbon-like section, resulting in smaller chips that are easier to clear. During cutting, multiple teeth are in simultaneous contact with the workpiece, reducing chatter and vibration. Rapid stock removal with heavy milling cuts is sometimes called hogging. Roughing end mills are also sometimes known as "rippa" or "ripper" cutters.

Ball cutter

Ball nose cutters or ball end mills (lower row in image) are similar to slot drills, but the end of the cutters are hemispherical. They are ideal for machining 3-dimensional contoured shapes in machining centres, for example in moulds and dies. They are sometimes called ball mills in shop-floor slang, despite the fact that that term also has another meaning. They are also used to add a radius between perpendicular faces to reduce stress concentrations.

A bull nose cutter mills a slot with a corner radius, intermediate between an end mill and ball cutter; for example, it may be a 20 mm diameter cutter with a 2 mm radius corner. The silhouette is essentially a rectangle with its corners truncated (by either a chamfer or radius).

Slab mill

Slab mills are used either by themselves or in gang milling operations on manual horizontal or universal milling machines to machine large broad surfaces quickly. They have been superseded by the use of cemented carbide-tipped face mills which are then used in vertical mills or machining centres.

Side-and-face cutter

The side-and-face cutter is designed with cutting teeth on its side as well as its circumference. They are made in varying diameters and widths depending on the application. The teeth on the side allow the cutter to make unbalanced cuts (cutting on one side only) without deflecting the cutter as would happen with a slitting saw or slot cutter (no side teeth).

Cutters of this form factor were the earliest milling cutters developed. From the 1810s to at least the 1880s they were the most common form of milling cutter, whereas today that distinction probably goes to end mills. Traditionally, HSS side and face cutters are used to mill slots and grooves.

Involute gear cutter

· 10 diametrical pitch cutter

· Cuts gears from 26 through to 34 teeth

· 14.5 degree pressure angle

There are 8 cutters (excluding the rare half sizes) that will cut gears from 12 teeth through to a rack (infinite diameter).

Hob

These cutters are a type of form tool and are used in hobbing machines to generate gears. A cross-section of the cutter's tooth will generate the required shape on the workpiece, once set to the appropriate conditions (blank size). A hobbing machine is a specialised milling machine.

Thread mill

Whereas a hob engages the work much as a mating gear would (and cuts the blank progressively until it reaches final shape), a thread milling cutter operates much like an endmill, traveling around the work in a helical interpolation.

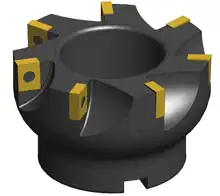

Face mill

A face mill is a cutter designed for facing as opposed to e.g., creating a pocket (end mills). The cutting edges of face mills are always located along its sides. As such it must always cut in a horizontal direction at a given depth coming from outside the stock. Multiple teeth distribute the chip load, and since the teeth are normally disposable carbide inserts, this combination allows for very large and efficient face milling.

Fly cutter

A fly cutter is composed of a body into which one or two tool bits are inserted. As the entire unit rotates, the tool bits take broad, shallow facing cuts. Fly cutters are analogous to face mills in that their purpose is face milling and their individual cutters are replaceable. Face mills are more ideal in various respects (e.g., rigidity, indexability of inserts without disturbing effective cutter diameter or tool length offset, depth-of-cut capability), but tend to be expensive, whereas fly cutters are very inexpensive.

Most fly cutters simply have a cylindrical center body that holds one tool bit. It is usually a standard left-hand turning tool that is held at an angle of 30 to 60 degrees. Fly cutters with two tool bits have no "official" name but are often called double fly cutters, double-end fly cutters, or fly bars. The latter name reflects that they often take the form of a bar of steel with a tool bit fastened on each end. Often these bits will be mounted at right angles to the bar's main axis, and the cutting geometry is supplied by using a standard right-hand turning tool.

Regular fly cutters (one tool bit, swept diameter usually less than 100 mm) are widely sold in machinists' tooling catalogs. Fly bars are rarely sold commercially; they are usually made by the user. Fly bars are perhaps a bit more dangerous to use than endmills and regular fly cutters because of their larger swing. As one machinist put it, running a fly bar is like "running a lawn mower without the deck",[2] that is, the exposed swinging cutter is a rather large opportunity to take in nearby hand tools, rags, fingers, and so on. However, given that a machinist can never be careless with impunity around rotating cutters or workpieces, this just means using the same care as always except with slightly higher stakes. Well-made fly bars in conscientious hands give years of trouble-free, cost-effective service for the facing off of large polygonal workpieces such as die/mold blocks.

Woodruff cutter

Woodruff cutters are used to cut the keyway for a Woodruff key.

Hollow mill

Hollow milling cutters, more often called simply hollow mills, are essentially "inside-out endmills". They are shaped like a piece of pipe (but with thicker walls), with their cutting edges on the inside surface. They were originally used on turret lathes and screw machines as an alternative to turning with a box tool, or on milling machines or drill presses to finish a cylindrical boss (such as a trunnion). Hollow mills can be used on modern CNC lathes and Swiss style machines. An advantage to using an indexable adjustable hollow mill on a Swiss-style machine is replacing multiple tools. By performing multiple operations in a single pass, the machine does not need as can accommodate other tools in the tool zone and improves productivity.

More advanced hollow mills use indexable carbide inserts for cutting, although traditional high speed steel and carbide-tipped blades are still used.

Hollow milling has an advantage over other ways of cutting because it can perform multiple operations. A hollow mill can reduce the diameter of a part and also perform facing, centering, and chamfering in a single pass.

Hollow mills offer an advantage over single point tooling. Multiple blades allow the feed rate to double and can hold a closer concentricity. The number of blades can be as many as 8 or as few as 3. For significant diameter removal (roughing), more blades are necessary.

Trepanning is also possible with a hollow mill. Special form blades can be used on a hollow mill for trepanning diameters, forms, and ring grooves.

Interpolation is also not necessary when using a hollow mill; this can result in a significant reduction of production time.

Both convex and concave spherical radii are possible with a hollow mill. The multiple blades of a hollow mill allow this radius to be produced while holding a tight tolerance.

A common use of a hollow mill is preparing for threading. The hollow mill can create a consistent pre-thread diameter quickly, improving productivity.

An adjustable hollow mill is a valuable tool for even a small machine shop to have because the blades can be changed out for an almost infinite number of possible geometries.

Shell mill

Modular principle

A shell mill is any of various milling cutters (typically a face mill or endmill) whose construction takes a modular form, with the shank (arbor) made separately from the body of the cutter, which is called a "shell" and attaches to the shank/arbor via any of several standardized joining methods.

This modular style of construction is appropriate for large milling cutters for about the same reason that large diesel engines use separate pieces for each cylinder and head whereas a smaller engine would use one integrated casting. Two reasons are that (1) for the maker it is more practical (and thus less expensive) to make the individual pieces as separate endeavors than to machine all their features in relation to each other while the whole unit is integrated (which would require a larger machine tool work envelope); and (2) the user can change some pieces while keeping other pieces the same (rather than changing the whole unit). One arbor (at a hypothetical price of USD100) can serve for various shells at different times. Thus 5 different milling cutters may require only USD100 worth of arbor cost, rather than USD500, as long as the workflow of the shop does not require them all to be set up simultaneously. It is also possible that a crashed tool scraps only the shell rather than both the shell and arbor. To also avoid damage to the shell, many cutters, especially in larger diameters, also have another replaceable part called shim, which is mounted to the shell and the inserts are mounted on the shim. That way, in case of light damage, only the insert and maximum the shim needs replacement. The shell is safe. This would be like crashing a "regular" endmill and being able to reuse the shank rather than losing it along with the flutes.

Most shell mills made today use indexable inserts for the cutting edges—thus shank, body, and cutting edges are all modular components.

Mounting methods

There are several common standardized methods of mounting shell mills to their arbors. They overlap somewhat (not entirely) with the analogous joining of lathe chucks to the spindle nose.

The most common type of joint between shell and arbor involves a fairly large cylindrical feature at center (to locate the shell concentric to the arbor) and two driving lugs or tangs that drive the shell with a positive engagement (like a dog clutch). Within the central cylindrical area, one or several socket head cap screws fasten the shell to the arbor.

Another type of shell fastening is simply a large-diameter fine thread. The shell then screws onto the arbor just as old-style lathe chuck backplates screw onto the lathe's spindle nose. This method is commonly used on the 2" or 3" boring heads used on knee mills. As with the threaded-spindle-nose lathe chucks, this style of mounting requires that the cutter only make cuts in one rotary direction. Usually (i.e., with right-hand helix orientation) this means only M03, never M04, or in pre-CNC terminology, "only forward, never reverse". One could use a left-hand thread if one needed a mode of use involving the opposite directions (i.e., only M04, never M03).

Using a milling cutter

Chip formation

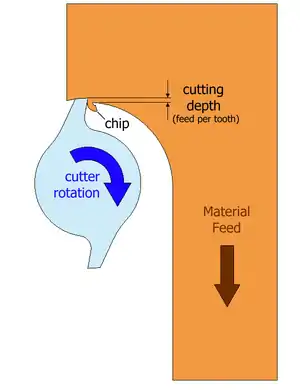

Although there are many different types of milling cutter, understanding chip formation is fundamental to the use of any of them. As the milling cutter rotates, the material to be cut is fed into it, and each tooth of the cutter cuts away a small chip of material. Achieving the correct size of chip is of critical importance. The size of this chip depends on several variables.

- Surface cutting speed (Vc)

- This is the speed at which each tooth cuts through the material as the tool spins. This is measured either in metres per minute in metric countries, or surface feet per minute (SFM) in America. Typical values for cutting speed are 10m/min to 60m/min for some steels, and 100m/min and 600m/min for aluminum. This should not be confused with the feed rate. This value is also known as "tangential velocity."

- Spindle speed (S)

- This is the rotation speed of the tool, and is measured in revolutions per minute (rpm). Typical values are from hundreds of rpm, up to tens of thousands of rpm.

- Diameter of the tool (D)

- Number of teeth (z)

- Feed per tooth (Fz)

- This is the distance the material is fed into the cutter as each tooth rotates. This value is the size of the deepest cut the tooth will make.Typical values could be 0.1 mm/tooth or 1 mm/tooth

- Feed rate (F)

- This is the speed at which the material is fed into the cutter. Typical values are from 20 mm/min to 5000 mm/min.

- Depth of cut

- This is how deep the tool is under the surface of the material being cut (not shown on the diagram). This will be the height of the chip produced. Typically, the depth of cut will be less than or equal to the diameter of the cutting tool.

The machinist needs three values: S, F and Depth when deciding how to cut a new material with a new tool. However, he will probably be given values of Vc and Fz from the tool manufacturer. S and F can be calculated from them:

| Spindle Speed | Feed rate |

|---|---|

| Looking at the formula for the spindle speed, S, it can be seen that larger tools require lower spindle speeds, while small tools may be able to go at high speeds. | The formula for the feed rate, F shows that increasing S or z gives a higher feed rate. Therefore, machinists may choose a tool with the highest number of teeth that can still cope with the swarf load. |

Conventional milling versus climb milling

A milling cutter can cut in two directions, sometimes known as conventional or up and climb or down.

- Conventional milling (left): The chip thickness starts at zero thickness, and increases up to the maximum. The cut is so light at the beginning that the tool does not cut, but slides across the surface of the material, until sufficient pressure is built up and the tooth suddenly bites and begins to cut. This deforms the material (at point A on the diagram, left), hardening it, and dulling the tool. The sliding and biting behaviour leaves a poor finish on the material.

- Climb milling (right): Each tooth engages the material at a definite point, and the width of the cut starts at the maximum and decreases to zero. The chips are disposed behind the cutter, leading to easier swarf removal. The tooth does not rub on the material, and so tool life may be longer. However, climb milling can apply larger loads to the machine, and so is not recommended for older milling machines or machines that are not in good condition. This type of milling is used predominantly on mills with a backlash eliminator.

Cutter location (cutter radius compensation)

Cutter location is the topic of where to locate the cutter in order to achieve the desired contour (geometry) of the workpiece, given that the cutter's size is non-zero. The most common example is cutter radius compensation (CRC) for endmills, where the centerline of the tool will be offset from the target position by a vector whose distance is equal to the cutter's radius and whose direction is governed by the left/right, climb/conventional, up/down distinction. In most implementations of G-code, it is G40 through G42 that control CRC (G40 cancel, G41 left/climb, G42 right/conventional). The radius values for each tool are entered into the offset register(s) by the CNC operator or machinist, who then tweaks them during production in order to keep the finished sizes within tolerance. Cutter location for 3D contouring in 3-, 4-, or 5-axis milling with a ball-endmill is handled readily by CAM software rather than manual programming. Typically the CAM vector output is postprocessed into G-code by a postprocessor program that is tailored to the particular CNC control model. Some late-model CNC controls accept the vector output directly, and do the translation to servo inputs themselves, internally.

Swarf removal

Another important quality of the milling cutter to consider is its ability to deal with the swarf generated by the cutting process. If the swarf is not removed as fast as it is produced, the flutes will clog and prevent the tool cutting efficiently, causing vibration, tool wear and overheating. Several factors affect swarf removal, including the depth and angle of the flutes, the size and shape of the chips, the flow of coolant, and the surrounding material. It may be difficult to predict, but a good machinist will watch out for swarf build up, and adjust the milling conditions if it is observed.

Selecting a milling cutter

Selecting a milling cutter is not a simple task. There are many variables, opinions and lore to consider, but essentially the machinist is trying to choose a tool that will cut the material to the required specification for the least cost. The cost of the job is a combination of the price of the tool, the time taken by the milling machine, and the time taken by the machinist. Often, for jobs of a large number of parts, and days of machining time, the cost of the tool is lowest of the three costs.

- Material: High speed steel (HSS) cutters are the least-expensive and shortest-lived cutters. Cobalt-bearing high speed steels generally can be run 10% faster than regular high speed steel. Cemented carbide tools are more expensive than steel, but last longer, and can be run much faster, so prove more economical in the long run. HSS tools are perfectly adequate for many applications. The progression from regular HSS to cobalt HSS to carbide could be viewed as very good, even better, and the best. Using high speed spindles may preclude use of HSS entirely.

- Diameter: Larger tools can remove material faster than small ones, therefore the largest possible cutter that will fit in the job is usually chosen. When milling an internal contour, or concave external contours, the diameter is limited by the size of internal curves. The radius of the cutter must be less than or equal to the radius of the smallest arc.

- Flutes: More flutes allows a higher feed rate, because there is less material removed per flute. But because the core diameter increases, there is less room for swarf, so a balance must be chosen.

- Coating: Coatings, such as titanium nitride, also increase initial cost but reduce wear and increase tool life. TiAlN coating reduces sticking of aluminium to the tool, reducing and sometimes eliminating need for lubrication.

- Helix angle: High helix angles are typically best for soft metals, and low helix angles for hard or tough metals.

History

The history of milling cutters is intimately bound up with that of milling machines. Milling evolved from rotary filing, so there is a continuum of development between the earliest milling cutters known, such as that of Jacques de Vaucanson from about the 1760s or 1770s,[3][4] through the cutters of the milling pioneers of the 1810s through 1850s (Whitney, North, Johnson, Nasmyth, and others),[5] to the cutters developed by Joseph R. Brown of Brown & Sharpe in the 1860s, which were regarded as a break from the past[6][7] for their large step forward in tooth coarseness and for the geometry that could take successive sharpenings without losing the clearance (rake, side rake, and so on). De Vries (1910)[7] reported, "This revolution in the science of milling cutters took place in the States about the year 1870, and became generally known in Europe during the Exhibition in Vienna in 1873. However strange it may seem now that this type of cutter has been universally adopted and its undeniable superiority to the old European type is no longer doubted, it was regarded very distrustfully and European experts were very reserved in expressing their judgment. Even we ourselves can remember that after the coarse pitched cutter had been introduced, certain very clever and otherwise shrewd experts and engineers regarded the new cutting tool with many a shake of the head. When[,] however, the Worlds Exhibition at Philadelphia in 1876, exhibited to European experts a universal and many-sided application of the coarse pitched milling cutter which exceeded even the most sanguine expectations, the most far-seeing engineers were then convinced of the immense advantages which the application of the new type opened up for the metalworking industry, and from that time onwards the American type advanced, slowly at first, but later on with rapid strides".[8]

Woodbury provides citations[9] of patents for various advances in milling cutter design, including irregular spacing of teeth (1867), forms of inserted teeth (1872), spiral groove for breaking up the cut (1881), and others. He also provides a citation on how the introduction of vertical mills brought about wider use of the endmill and fly cutter types.[10]

Scientific study by Holz and De Leeuw of the Cincinnati Milling Machine Company[11] made the teeth even coarser and did for milling cutters what F.W. Taylor had done for single-point cutters with his famous scientific cutting studies.

See also

Citations

- ↑ Rapid Traverse: More Teeth Per Flute Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ J.Ramsey, "Max Diameter for a Flycutter?", PracticalMachinist.com discussion board, retrieved 2011-06-05.

- ↑ Woodbury 1972, p. 23.

- ↑ Roe 1916, p. 206.

- ↑ Woodbury 1972, pp. 51–52.

- ↑ Woodbury 1972, pp. 51–55.

- 1 2 De Vries 1910, p. 15.

- ↑ De Vries 1910, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Woodbury 1972, p. 54.

- ↑ Woodbury 1972, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Woodbury 1972, pp. 79–81.

General bibliography

- De Vries, D. (1910), Milling machines and milling practice: a practical manual for the use of manufacturers, engineering students and practical men, London: E. & F.N. Spon. Co-edition: New York, Spon & Chamberlain, 1910.

- Roe, Joseph Wickham (1916), English and American Tool Builders, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, LCCN 16011753. Reprinted by McGraw-Hill, New York and London, 1926 (LCCN 27-24075); and by Lindsay Publications, Inc., Bradley, Illinois (ISBN 978-0-917914-73-7).

- Woodbury, Robert S. (1972) [1960], "History of the Milling Machine", Studies in the History of Machine Tools, Cambridge, Mass., and London: MIT Press, ISBN 978-0-262-73033-4, LCCN 72006354. First published alone as a monograph in 1960.

External links

Media related to Milling heads at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Milling heads at Wikimedia Commons