| Wreck of the Titanic | |

|---|---|

The Titanic's bow, photographed in June 2004 | |

| Event | Sinking of the Titanic |

| Cause | Collision with an iceberg |

| Date | 15 April 1912 |

| Location | 370 nmi (690 km) south-southeast of Newfoundland, North Atlantic Ocean |

| Coordinates | 41°43′32″N 49°56′49″W / 41.72556°N 49.94694°W[1] |

| Discovered | 1 September 1985 |

The wreck of the Titanic lies at a depth of about 12,500 feet (3,800 metres; 2,100 fathoms), about 370 nautical miles (690 kilometres) south-southeast off the coast of Newfoundland. It lies in two main pieces about 2,000 feet (600 m) apart. The bow is still recognisable with many preserved interiors, despite deterioration and damage sustained hitting the sea floor. In contrast, the stern is heavily damaged. A debris field around the wreck contains hundreds of thousands of items spilled from the ship as she sank. The bodies of the passengers and crew would also be distributed across the sea bed, but have since been consumed by other organisms.

The Titanic sank in 1912, when she collided with an iceberg during her maiden voyage. Numerous expeditions unsuccessfully tried using sonar to map the sea bed in the hope of finding the wreckage. In 1985, the wreck was finally located by a joint French–American expedition led by Jean-Louis Michel of IFREMER and Robert Ballard of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. The wreck has been the focus of intense interest and has been visited by numerous tourist and scientific expeditions, including by the submersible Titan, which imploded near the wreck in June 2023, killing all five aboard.

Controversial salvage operations have recovered thousands of items from the Titanic, which have been conserved and put on public display. Many schemes have been proposed to raise the wreck, including filling it with ping-pong balls,[2] injecting it with 180,000 tons of Vaseline,[3] or using half a million tons of liquid nitrogen to encase it in an iceberg that would float to the surface.[4] However, the wreck is too fragile to be raised and is protected by a UNESCO convention.

Salvaging the Titanic

Almost immediately after the Titanic sank on 15 April 1912, proposals were advanced to salvage it from its resting place in the North Atlantic Ocean, despite her exact location and condition being unknown. The families of several wealthy victims of the disaster – the Guggenheims, Astors, and Wideners – formed a consortium and contracted the Merritt and Chapman Derrick and Wrecking Company to raise the Titanic.[5] The project was soon abandoned as impractical as the divers could not even reach a significant fraction of the necessary depth, where the pressure is over 6,000 pounds per square inch (40 megapascals), about 400 standard atmospheres. The company considered dropping dynamite on the wreck to dislodge bodies which would float to the surface, but finally gave up after oceanographers suggested that the extreme pressure would have compressed the bodies into gelatinous lumps.[6] In fact, this was incorrect. Whale falls, a phenomenon not discovered until 1987—coincidentally, by the same submersible used for the first crewed expedition to the Titanic the year before[7]—demonstrate that water-filled corpses, in this case cetaceans, can sink to the bottom essentially intact.[8] The high pressure and low temperature of the water would have prevented significant quantities of gas forming during decomposition, preventing the bodies of Titanic victims from rising back to the surface.[9]

In later years, numerous proposals were put forward to salvage the Titanic. However, all fell afoul of practical and technological difficulties, a lack of funding and, in many cases, a lack of understanding of the physical conditions at the wreck site. Charles Smith, a Denver architect, proposed in March 1914 to attach electromagnets to a submarine which would be irresistibly drawn to the wreck's steel hull. Having found its exact position, more electromagnets would be sent down from a fleet of barges which would winch the Titanic to the surface.[10] An estimated cost of US$1.5 million ($35.5 million today) and its impracticality meant that the idea was not put into practice. Another proposal involved raising the Titanic by means of attaching balloons to her hull using electromagnets. Once enough balloons had been attached, the ship would float gently to the surface. Again, the idea got no further than the drawing board.[11]

Salvage proposals in the 1960s and 1970s

In the mid-1960s, a hosiery worker from Baldock, England, named Douglas Woolley devised a plan to find the Titanic using a bathyscaphe and raise the wreck by inflating nylon balloons that would be attached to her hull.[12] The declared objective was to "bring the wreck into Liverpool and convert it to a floating museum".[13] The Titanic Salvage Company was established to manage the scheme and a group of businessmen from West Berlin set up an entity called Titanic-Tresor to support it financially.[12] The project collapsed when its proponents found they could not overcome the problem of how the balloons would be inflated in the first place. Calculations showed that it could take ten years to generate enough gas to overcome the water pressure.[14]

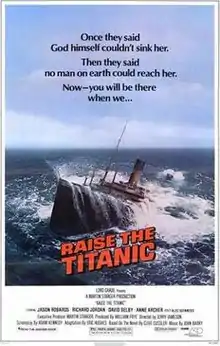

A variety of proposals to salvage the ship were made during the 1970s. One called for 180,000 tons of molten wax (or alternatively, Vaseline) to be pumped into the Titanic, lifting her to the surface.[3] Another proposal involved filling the Titanic with ping-pong balls, but overlooked the fact that the balls would be crushed by the pressure long before reaching the depth of the wreck.[2] A similar idea involving the use of Benthos glass spheres, which could survive the pressure, was scuppered when the cost of the number of spheres required was put at over $238 million.[3] An unemployed haulage contractor from Walsall named Arthur Hickey proposed to encase the Titanic inside an iceberg, freezing the water around the wreck in a buoyant jacket of ice. The ice, being less dense than liquid water, would float to the surface and could be towed to shore. The BOC Group calculated that this would require half a million tons of liquid nitrogen to be pumped down to the sea bed.[4] In his 1976 thriller Raise the Titanic!, author Clive Cussler's hero Dirk Pitt repairs the holes in the Titanic's hull, pumps it full of compressed air and succeeds in making it "leap out of the waves like a modern submarine blowing its ballast tanks", a scene depicted on the posters of the subsequent film of the book. Although this was an "artistically stimulating" highlight of the film,[15] made using a 55-foot (17 m) model of the Titanic, it would not have been physically possible.[16] At the time of the book's writing, it was still believed that the Titanic sank in one piece.

Robert Ballard of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution had long been interested in finding the Titanic. Despite early negotiations with possible backers being abandoned when it emerged that they wanted to turn the wreck into souvenir paperweights, more sympathetic backers joined Ballard to form a company named Seasonics International Ltd. as a vehicle for rediscovering and exploring the Titanic. In October 1977, he made his first attempt to find the ship with the aid of the Alcoa Corporation's deep sea salvage vessel Seaprobe. This was essentially a drillship with sonar equipment and cameras attached to the end of the drilling pipe. It could lift objects from the seabed using a remote-controlled mechanical claw.[17] The expedition ended in failure when the drilling pipe broke, sending 3,000 feet (900 m) of pipe and US$600,000 (equivalent to $2,897,529 in 2022) worth of electronics plunging to the sea bed.[17]

In 1978, The Walt Disney Company and National Geographic magazine considered mounting a joint expedition to find the Titanic, using the aluminium submersible Aluminaut. The Titanic would have been well within the submersible's depth limits, but the plans were abandoned for financial reasons.[12]

The next year, the British billionaire financier and tycoon Sir James Goldsmith set up Seawise & Titanic Salvage Ltd. with the involvement of underwater diving and photographic experts. His aim was to use the publicity of finding the Titanic to promote his newly established magazine, NOW!. An expedition to the North Atlantic was scheduled for 1980 but was cancelled due to financial difficulties.[12] A year later, NOW! folded after 84 issues with Goldsmith incurring huge financial losses.[18]

Fred Koehler, an electronics repairman from Coral Gables, Florida, sold his electronics shop to finance the completion of a two-man deep-sea submersible called Seacopter. He planned to dive to the Titanic, enter the hull and retrieve a fabulous collection of diamonds rumoured to be contained in the purser's safe. However, he was unable to obtain financial backing for his planned expedition.[19] Another proposal involved using a semi-submersible platform mounted with cranes, resting on two watertight supertankers, that would winch the wreck off the seabed and carry it to shore.[20]

Jack Grimm's expeditions, 1980–1983

On 17 July 1980, an expedition sponsored by Texan oilman Jack Grimm set off from Port Everglades, Florida, in the research vessel H.J.W. Fay. Grimm had previously sponsored expeditions to find Noah's Ark, the Loch Ness Monster, Bigfoot, and the giant hole in the North Pole predicted by the pseudoscientific Hollow Earth hypothesis. To raise funds for his Titanic expedition, he obtained sponsorship from friends with whom he played poker, sold media rights through the William Morris Agency, commissioned a book, and obtained the services of Orson Welles to narrate a documentary. He acquired scientific support from Columbia University by donating $330,000 to the Lamont–Doherty Geological Observatory for the purchase of a wide-sweep sonar, in exchange for five years' use of the equipment and the services of technicians to support it. Drs. William B. F. Ryan of Columbia University and Fred Spiess of Scripps Institution of Oceanography in California joined the expedition as consultants.[21] The expedition was almost cancelled when Grimm asked them to use a monkey trained to point at a spot on the map to supposedly indicate where the Titanic was. The scientists issued an ultimatum: "It's either us or the monkey." Grimm preferred the monkey, but was prevailed upon to take the scientists instead.[22]

The results were inconclusive, as three weeks of surveying in almost continuous bad weather during July and August 1980 failed to find the Titanic. The problem was exacerbated by technological limitations; the Sea MARC sonar used by the expedition had a relatively low resolution and was a new and untested piece of equipment. It was nearly lost only 36 hours after it was first deployed when the tail was ripped off during a sharp turn, destroying the magnetometer, which would have been vital for detecting the Titanic's hull. Nonetheless, it surveyed an area of some 500 square nautical miles (1,700 square kilometres) and identified 14 possible targets.[22] A documentary of this expedition, featuring Welles, was titled Search for the Titanic (1981).[23]

Grimm mounted a second expedition in June 1981 aboard the research vessel Gyre, with Spiess and Ryan again joining the expedition.[23] To increase their chances of finding the wreck, the team employed a much more capable sonar device, the Scripps Deep Tow. The weather was again very poor, but all 14 of the targets were successfully covered and found to be natural features. On the last day of the expedition, an object that looked like a propeller was found.[24] Grimm announced on his return to Boston that the Titanic had been found, but the scientists declined to endorse his identification.[25] A documentary of this expedition, featuring James Drury, was titled Return to the Titanic (1981). This and the previous film were later combined into a single production, In Search of Titanic (1981).

In July 1983, Grimm went back a third time with Ryan aboard the research vessel Robert D. Conrad. Nothing was found and bad weather brought an early end to the expedition. Although they did not know it at the time, the Sea MARC had passed over the Titanic but failed to detect it,[25] while Deep Tow had passed within 1+1⁄2 nautical miles (3 km) of the wreck.[26]

Discovery

D. Michael Harris and Jack Grimm failed to find the Titanic but their expeditions did succeed in producing fairly detailed mapping of the area in which the ship sank.[25] It was clear that the position given in the Titanic's distress signals was inaccurate, which was a major expedition difficulty because it increased the search area's already-expansive size. Despite the failure of his 1977 expedition, Ballard had not given up hope and devised new technologies and a new search strategy to tackle the problem. The new technology was a system called Argo / Jason. This consisted of a remotely controlled deep-sea vehicle called Argo, equipped with sonar and cameras and towed behind a ship, with a robot called Jason tethered to it that could roam the sea floor, take close-up images and gather specimens. The images from the system would be transmitted back to a control room on the towing vessel where they could be assessed immediately. Although it was designed for scientific purposes, it also had important military applications and the United States Navy agreed to sponsor the system's development,[27] on condition that it was to be used to carry out a number of programmes—many still classified—for the Navy.[28]

The Navy commissioned Ballard and his team to carry out a month-long expedition every year for four years, to keep Argo / Jason in good working condition.[29] It agreed to Ballard's proposal to use some of the time to search for the Titanic once the Navy's objectives had been met; the search would provide an ideal opportunity to test Argo / Jason. In 1984 the Navy sent Ballard and Argo to map the wrecks of the sunken nuclear submarines USS Thresher and USS Scorpion, lost in the North Atlantic at depths of up to 9,800 ft (3,000 m).[30] The expedition found the submarines and made an important discovery about how shipwrecks behave as they sink. As Thresher and Scorpion sank, debris spilled out from them across a wide area of the seabed and was sorted by the currents, so that light debris drifted furthest away from the site of the sinking. This debris field was far larger than the wrecks themselves. By following the comet-like trail of debris, the main pieces of wreckage could be found.[31]

A second expedition to map the wreck of Scorpion was mounted in 1985. Only twelve days' search time would be left at the end of the expedition to look for the Titanic.[30] As Harris/Grimm's unsuccessful efforts had taken more than forty days,[25] Ballard decided that extra help would be needed. He approached the French national oceanographic agency, IFREMER, with which Woods Hole had previously collaborated. The agency had recently developed a high-resolution side-scan sonar called SAR and agreed to send a research vessel, Le Suroît, to survey the sea bed in the area where the Titanic was believed to lie. The idea was for the French to use the sonar to find likely targets, and then for the Americans to use Argo to check out the targets and hopefully confirm whether they were in fact the wreck.[32] The French team spent five weeks, from 5 July to 12 August 1985, "mowing the lawn" – sailing back and forth across the 150-square-nautical-mile (510-square-kilometre) target area to scan the sea bed in a series of stripes. However, they found nothing; though it turned out that they had passed within a few hundred yards of the Titanic in their first run.[33]

Ballard realised that looking for the wreck itself using sonar was unlikely to be successful and adopted a different tactic, drawing on the experience of the surveys of Thresher and Scorpion; he would look for the debris field instead,[34] using Argo's cameras rather than sonar. While sonar could not distinguish human-made debris on the sea bed from natural objects, cameras could. The debris field would also be a far bigger target, stretching one nautical mile (1.9 kilometres) or longer, whereas the Titanic itself was only 90 feet (27 m) wide.[35] The search required round-the-clock towing of Argo back and forth above the sea bed, with shifts of watchers aboard the research vessel Knorr looking at the camera pictures for any sign of debris.[36] After a week's fruitless searching, at 12:48 am on Sunday 1 September 1985, pieces of debris began to appear on Knorr's screens. One of them was identified as a boiler, identical to those shown in pictures from 1911.[37] The following day, the main part of the wreck was found and Argo sent back the first pictures of the Titanic since her sinking 73 years before.[38] The discovery made headlines around the world.[39]

Subsequent expeditions

1986–1998

Following his discovery of the wreck site, Ballard returned to the Titanic in July 1986 aboard the research vessel RV Atlantis II. Now the deep-diving submersible DSV Alvin could take people back to the Titanic for the first time since her sinking, and the remotely operated vehicle Jason Jr. would allow the explorers to investigate the interior of the wreck. Another system, ANGUS, was used to carry out photo surveys of the debris field.[40] Jason Jr. descended the ruined Grand Staircase as far as B Deck, and photographed remarkably well-preserved interiors, including some chandeliers still hanging from the ceilings.[41]

Between 25 July and 10 September 1987, an expedition mounted by IFREMER and a consortium of American investors which included George Tulloch, G. Michael Harris, D. Michael Harris and Ralph White made 32 dives to the Titanic using the submersible Nautile. Controversially, they salvaged and brought ashore more than 1,800 objects.[42] A joint Russian-Canadian-American expedition took place in 1991 using the research vessel Akademik Mstislav Keldysh and its two MIR submersibles. Sponsored by Stephen Low and IMAX, CBS, National Geographic and others, the expedition carried out extensive scientific research with a crew of 130 scientists and engineers. The MIRs carried out 17 dives, spending over 140 hours at the bottom, shooting 40,000 feet (12,000 m) of IMAX film. This was used to create the 1992 documentary film Titanica, which was later released in the US on DVD in a re-edited version narrated by Leonard Nimoy.[43][44]

IFREMER and RMS Titanic Inc., the successors to the sponsors of the 1987 expedition, returned to the wreck with Nautile and the ROV Robin in June 1993. Over the course of fifteen days, Nautile made fifteen dives lasting between eight and twelve hours each.[45] Another 800 artefacts were recovered during the expedition including a two-tonne piece of a reciprocating engine, a lifeboat davit and the steam whistle from the ship's forward funnel.[46]

In 1993, 1994, 1996 and 1998 RMS Titanic Inc. carried out an intensive series of dives that led to the recovery of over 4,000 items in the first two expeditions alone.[47] The 1996 expedition controversially attempted to raise a section of the Titanic itself, a section of the outer hull that originally comprised part of the wall of two first-class cabins on C Deck, extending down to D Deck. It weighed 20 tons,[48][49] measured 15 by 25 feet (4.6 m × 7.6 m) and had four portholes in it, three of which still had glass in them.[50] The section had come loose either during the sinking or as a result of the impact with the sea bed.[51][49]

Its recovery using diesel-filled flotation bags was turned into something of an entertainment event, with two cruise ships accompanying the expedition to the wreck site.[52][53][54][55][56][57] Passengers were offered the chance, at $5,000 per person, to watch the recovery on television screens in their cabins[52][53][54][57][58] while enjoying luxury accommodation, Las Vegas–style shows, and casino gambling aboard the ships.[55] Various celebrities were recruited to enliven the proceedings, including Burt Reynolds, Debbie Reynolds and Buzz Aldrin,[49][52][57][58] and "grand receptions" for VIPs were scheduled on-shore where the hull section would be displayed.[55]

However the lift ended disastrously when rough weather caused the ropes supporting the bags to snap.[56] At the moment the ropes broke, the hull section had been lifted to within only 200 feet (60 m) of the surface.[54] It hurtled 12,000 feet (3,700 m) back down,[59] embedding itself upright on the sea floor.[54][56] The attempt was strongly criticised by marine archaeologists, scientists, and historians as a money-making publicity stunt;[48][49][52][54][55] several publications compared the event to grave robbing,[52][54][55][56] and Ballard called the event "a carnival" and stated that "We tried to put it to rest, but this perpetuates the tragedy."[55][58] A second, successful attempt to lift the fragment was carried out in 1998.[48][49] The so-called "Big Piece" was conserved in a laboratory in Santa Fe for two years before being put on display at the Luxor Las Vegas hotel and casino.[60]

In 1995, Canadian director James Cameron chartered the Akademik Mstislav Keldysh and the MIRs to make 12 dives to the Titanic. He used the footage in his blockbuster 1997 film Titanic.[61] The discovery of the wreck and a National Geographic documentary of Ballard's 1986 expedition had inspired him to write a synopsis in 1987 of what eventually became the film: "Do story with bookends of present day scene of wreck using submersibles intercut with memories of a survivor and re-created scenes of the night of the sinking. A crucible of human values under stress."[62]

2000–present

The 2000 expedition by RMS Titanic Inc. carried out 28 dives during which over 800 artefacts were recovered, including the ship's engine telegraphs, perfume vials and watertight door gears.[63]

In 2001, an American couple—David Leibowitz and Kimberly Miller[64]—caused controversy when they were married aboard a submersible that had set down on the bow of the Titanic, in a deliberate echo of a famous scene from James Cameron's 1997 film. The wedding was essentially a publicity stunt, sponsored by a British company called SubSea Explorer which had offered a free dive to the Titanic that Leibowitz had won. He asked whether his fiancée could come too and was told that she could—but only if she agreed to get married during the trip.[65]

The same company also brought along Philip Littlejohn, the grandson of one of the Titanic's surviving crew members, who became the first descendant of a Titanic passenger or crew member to visit the wreck.[66] Cameron himself also returned to the Titanic in 2001 to carry out filming for Walt Disney Pictures' Ghosts of the Abyss, filmed in 3D.[66]

In 2003 and 2004, the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration carried out two expeditions to the Titanic. The first, carried out between 22 June and 2 July 2003, performed four dives in two days. Its key aims were to assess the current condition of the wreck site and carry out scientific observations to support ongoing research. The stern section, which had previously received relatively little attention from explorers, was specifically targeted for analysis. The microbial colonies aboard the Titanic were also a key focus of investigation.[67] The second expedition, from 27 May – 12 June 2004, saw the return of Robert Ballard to the Titanic nearly 20 years after he discovered it. The expedition spent 11 days on the wreck, carrying out high-resolution mapping using video and stereoscopic still images.[68]

In 2005 there were two expeditions to the Titanic. James Cameron returned for the third and last time to film Last Mysteries of the Titanic. Another expedition searched for previously unseen pieces of wreckage, and led to the documentary Titanic's Final Moments: Missing Pieces.

RMS Titanic Inc. mounted further expeditions to the Titanic in 2004[69] and 2010, when the first comprehensive map of the entire debris field was produced. Two autonomous underwater vehicles—torpedo-shaped robots—repeatedly ran backward and forward across the 3-by-5-nautical-mile (6 km × 9 km) debris field, taking sonar scans and over 130,000 high-resolution images. This enabled a detailed photomosaic of the debris field to be created for the first time, giving scientists a much clearer view of the dynamics of the ship's sinking. The expedition encountered difficulties: several hurricanes passed over the wreck site, and the Remora ROV was caught in a piece of wreckage. This same year saw the discovery of the new bacteria living in the rusticles on the Titanic, Halomonas titanicae.[70]

Tourist and scientific visits to the Titanic still continue; by April 2012, 100 years since the disaster and nearly 25 since the discovery of the wreck, around 140 people had visited.[71] On 14 April 2012 (the 100th anniversary of the ship's sinking), the wreck of the Titanic became eligible for protection under the 2001 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage.[72] In the same month, Robert Ballard, the wreck's discoverer, announced a plan to preserve the wreck of the Titanic by using deep-sea robots to paint the wreck with anti-fouling paint, to help keep the wreck in its current state for all time. The proposed plan that Ballard announced has been outlined in a documentary made to time with the Titanic's 100th sinking anniversary called Save the Titanic With Bob Ballard where Ballard himself talks about how this proposed paint job on the wreck will work. Ballard says that he proposed to robotically clean and repaint the Titanic with a colour scheme mimicking rusticles because he saw "original anti-fouling paint on the ship's hull, which was still working even after 74 years on the seabed" when he visited the Titanic in 1986.[73]

In August 2019, a team of explorers and scientists used deep-submergence vehicle Limiting Factor to visit the wreck, marking the first crewed dive to the ship in 14 years. Five dives took place over a period of eight days. The team used specially adapted cameras to capture the wreck in 4K resolution for the first time, and dedicated photogrammetry passes were performed to create highly accurate and photoreal 3D models of the wreck. Footage from the dive was used for a documentary film by Atlantic Productions.[74] The documentary, Back to the Titanic, aired on National Geographic in 2020.[75]

In May 2023, the mapping company Magellan and the film production company Atlantic Productions created the first full-sized digital scan of the Titanic, using deep-sea mapping. The 3D view of the entire ship enables it to be seen as if the water has been drained away. It is hoped the scan can shed new light on the sinking.[76]

American company OceanGate began conducting commercial submersible tours of the wreck in July 2021 using its submersible Titan.[77] On 18 June 2023, Titan imploded near the wreck during a dive, killing its pilot and four passengers.[78][79][80]

Description

The location of the wreck is a considerable distance from the location transmitted by the ship's wireless operators before she went down. The Titanic is in two main pieces 370 nautical miles (690 km) southeast of Mistaken Point, Newfoundland and Labrador. The boilers found by Argo, which mark the point at which the ship went down,[81] are about 600 feet (180 m) east of the stern. The two main parts of the wreck of the Titanic present a striking contrast. Although fourteen survivors testified that the ship had broken apart as she sank, this testimony was discounted by the official inquiries, and it was supposed that the ship had sunk intact.[82] It is now clear that the stresses on the Titanic caused the ship to split apart between the second and third funnels at or just below the surface.[83]

Bow section

The bow section, which measures about 470 feet (140 m) long, is thought to have descended at an angle of about 45°. Its distance from the stern was caused by its planing forward horizontally by about 1 ft for every 6 ft (1 m for every 6 m) of its descent.[84] During the descent to the sea bed, the funnels were swept away, taking with them the rigging and large lengths of cables. These dragged along the boat deck, tearing away many of the davits and much of the other deck equipment.[85] The foremast was also torn down, falling onto the port bridge area. The ship's wheelhouse was swept away, possibly after being hit by the falling foremast.[83]

The bow hit the bottom at a speed of about 20 knots (10 metres per second), digging about 60 feet (20 m) deep into the mud, up to the base of the anchors. The impact bent the hull in two places and caused it to buckle downwards by about 10° under the forward well deck cranes and by about 4° under the forward expansion joint. When the bow section hit the sea bed, the weakened decks at the rear, where the ship had broken apart, collapsed on top of each other.[84] The forward hatch cover was also blown off and landed a couple of hundred feet in front of the bow, possibly due to the force of water being pushed out as the bow impacted the bottom.[86]

The area around the bridge is particularly badly damaged; as Robert Ballard has put it, it looks "as if it had been squashed by a giant's fist".[87] The roof of the officers' quarters and the sides of the gymnasium appear pushed in, railings were bent outwards and vertical steel columns supporting the decks were bent into a C-shape. Charles R. Pellegrino has proposed that this was the result of a "down-blast" of water, caused by a slipstream that had followed the bow section as it fell towards the sea bed. According to Pellegrino's hypothesis, when the bow came to an abrupt halt the inertia of the slipstream caused a rapidly moving column of water weighing thousands of tons to strike the top of the wreck, striking it near the bridge. This, argues Pellegrino, caused large parts of the bow's interior to be demolished by surges of water and violent eddies kicked up by the wreck's sudden halt.[88] The damage caused by the collision with the iceberg is not visible at the bow as it is buried under mud.[89]

Interiors

Despite the exterior devastation caused by the bow's descent and collision with the ocean floor, there are parts of the interior in reasonably good condition. The bow's slow flooding and its relatively smooth descent to the sea floor mitigated interior damage. The stairwell of the First-Class Grand Staircase between the Boat Deck and E Deck is an empty chasm within the wreck, providing a convenient point of access for ROVs. Dense rusticles hanging from the steel decking combined with the deep layers of silt that have accumulated in the interior make navigating the wreck disorienting.

Passenger staterooms have largely deteriorated because they were framed in perishable softwoods such as pine, leaving hanging electrical wire, light fixtures and debris interspersed with more durable items like brass bed frames, light fixtures, and marble-topped washstands. Woodwork with attachments like doorknobs, drawer-pulls or push-plates have survived in better condition because of the small electric charge emitted by metal which repels fish and other organisms. Hardwoods like teak and mahogany, the material for most stateroom furnishings, are more resistant to decay. Lavatories and bathrooms within the passenger quarters have resisted decay because they were framed in steel.

The only intact public rooms remaining in either the stern or bow sections are the First-Class Reception Room and Dining Saloon, both on D-Deck. Most of the Dining Saloon has collapsed because of its proximity to the break-up point midship, but the very forward part is accessible and the rectangular leaded glass windows, table bases, and ceiling lamps are noticeably preserved. The Reception Room with its leaded glass windows and mahogany panelling remains remarkably intact, although the ceiling is sagging and there is a deep layer of silt obstructing the floor.[90][91] The Turkish Baths on F-Deck were found to be in excellent condition during their rediscovery in 2005, preserving the blue-green tiles, carved teak woodwork, and inlaid furniture.[92] The Grand Staircase was likely destroyed during the sinking, but the surrounding first-class foyers and elevator entrances preserve many of the ormolu and crystal lamps, oak timbers, and oak-framed stanchions.[93]

In addition to the passenger areas, crew areas like the firemen's mess, dormitories, parts of "Scotland Road" on E-Deck and the cargo holds on the Orlop Deck have also been explored. The Ghosts of the Abyss expedition in 2001 attempted to locate the famed Renault automobile belonging to William Carter, but the cargo was indistinguishable beneath the silt and rusticles.[94]

Stern section

The stern of the ship, which measures about 350 feet (105 m) long, was catastrophically damaged during the descent and landing on the sea bed. It had not fully filled with water when it sank, and the increasing water pressure caused trapped air pockets to implode, tearing apart the hull. It was loud enough that multiple survivors reported hearing explosions about ten seconds after the stern had sunk beneath the waves. Data from a sonar map made during a 2010 expedition showed that the stern rotated like a helicopter blade as it sank.[95]

The rudder appears to have swung over to an angle of about 30 to 45° during the stern's descent, causing the section to follow a tight spiral to the bottom.[96] It probably struck rudder-first, burying most of the rudder in the mud up to a depth of 50 feet (15 m).[97] The decks pancaked one atop another and the hull plating splayed out to the sides of the shattered section.[83] The pancaking is so severe that the combined height of the decks, which are piled up on top of the reciprocating engines, is now generally not more than about 12 to 15 feet (3.7 to 4.6 m) high. No individual deck is more than about 1 foot (30 cm) high.[97]

Large sections of the hull plating appear to have fallen off well before the wreck hit the bottom.[98] One such section, thought to have been from the galleys, separated from the stern in one piece and landed nearby.[85] The force of the water tore up the poop deck and folded it back on itself. The centre propeller is totally buried, while the force of the impact caused the two wing propellers and shafts to be bent upwards by an angle of about 20°.[98]

A large V-shaped section of the ship just aft of midships, running from the keel upwards through Number 1 Boiler Room and upwards to cover the area under funnel numbers three and four, was believed to have disintegrated entirely when the ship broke up. This was one of the weakest parts of the ship as a result of the presence of two large open spaces – the forward end of the engine room and the aft First Class passenger staircase. The rest of this part of the ship is scattered across the seabed at distances of 130 to 260 feet (40 to 80 m) from the main part of the stern.[99]

During the 2010 expedition to map the wreck site, a major chunk of the deck house (the base of the third funnel) along with pieces of the third funnel were found. This showed that instead of simply disintegrating into a mass of debris, large sections of the ship broke off in chunks and that the ship broke in half between funnel numbers two and three, and not funnel numbers three and four. Five of the boilers from Number 1 Boiler Room came loose during its disintegration and landed in the debris field around the stern. Experts believe that this tight cluster of boilers marks the hypocentre of where the ship broke up 12,000 feet above.[100] The rest of the boilers are still presumably located in the bow section.[101]

Debris fields

As the Titanic broke apart, many objects and pieces of hull were scattered across the sea bed.[100] There are two debris fields in the vicinity of the wreck, each between 2,000–2,600 ft (600–800 m) long, trailing in a southwesterly direction from the bow and stern.[9] They cover an area of about 2 sq mi (5 km2).[102] Most of the debris is concentrated near the stern section of the Titanic.[103] It consists of thousands of objects from the interior of the ship, ranging from tons of coal spilled from ruptured bunkers to suitcases, clothes, corked wine bottles (many still intact despite the pressure), bathtubs, windows, washbasins, jugs, bowls, hand mirrors and numerous other personal effects.[104] The debris field also includes numerous pieces of the ship itself, with the largest pieces of debris in the vicinity of the partially disintegrated stern section. It is also believed that the remains of the ship's four funnels are in one of these debris fields.[100]

Condition and deterioration of the wreck

Prior to the discovery of the Titanic's wreck, in addition to the common assumption that she had sunk in one piece, it had been widely believed that conditions at 12,000 feet (3,700 metres) down would preserve the ship virtually intact. The water is bitterly cold at only about 1–2 °C (34–36 °F), there is no light, and the high pressure was thought to be likely to lower oxygen and salinity levels to the point that organisms would not be able to gain a foothold on the wreck. The Titanic would effectively be in a deep freeze.[105]

The reality has turned out to be very different, and the ship has increasingly deteriorated since she sank in April 1912. Her gradual decay is due to a number of different processes – physical, chemical and biological.[106] She is situated on an undulating, gently sloping area of seabed in Titanic Canyon, which is swept by the western boundary current. Eddies from the current flow constantly across the wreck, scouring the sea bed and keeping sediment from building up over the hull.[89] The current is strong and often changeable, gradually opening up holes in the ship's hull.[107] Salt corrosion eats away at the hull,[106] and it is also affected by galvanic corrosion.[107]

The most dramatic deterioration has been caused by biological factors. It used to be thought that the depths of the ocean were a lifeless desert, but research carried out since the mid-1980s has found that the ocean floor is teeming with life and may rival the tropical rainforests for biodiversity.[108] During the 1991 IMAX expedition, scientists were surprised by the variety of organisms that they found in and around the Titanic. A total of 28 species were observed, including sea anemones, crabs, shrimp, starfish, and rattail fish up to a yard (1 m) long.[89] Much larger creatures have been glimpsed by explorers.[109]

Some of the Titanic's fauna has never been seen anywhere else; James Cameron's 2001 expedition discovered a previously unknown type of sea cucumber, lavender with a glowing row of phosphorescent "portholes" along its side.[110] A newly discovered species of rust-eating bacterium found on the ship has been named Halomonas titanicae, which has been found to cause rapid decay of the wreck. Henrietta Mann, who discovered the bacteria, has estimated that the Titanic will completely collapse possibly as soon as 2030.[111] The Canadian geophysicist Steve Blasco has commented that the wreck "has become an oasis, a thriving ecosystem sitting in a vast desert".[89] In mid-2016, the facilities of the Institut Laue-Langevin used neutron imaging to demonstrate that a molecule called ectoine is used by Halomonas titanicae to regulate fluid balance and cell volume to survive at such pressures and salinities.[112]

Analysis by Henrietta Mann and Bhavleen Kaur, both of Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in conjunction with other scientists and researchers of the University of Seville in Spain, has determined that the wreck of the Titanic will not exist by 2037 and that preservation of the Titanic is impossible. "Unfortunately, because Titanic is 2.3 miles (3.7 km) down, it is very difficult or impossible to preserve. It is film which will preserve it for history now," says Mann. "It has already lasted for 100 years, but eventually there will be nothing left but a rust stain on the bottom of the Atlantic... I think Titanic has maybe 15 or 20 years left. I don't think it will have too much longer than that."[113] Other scientists estimated that the Titanic would last no longer than 14 years, as of 2017.[114]

The soft organic material aboard and dispersed onto the seabed around the hull would have been the first to disappear, rapidly devoured by fish and crustaceans. Wood-boring molluscs such as Teredo colonised the ship's decks and interior in huge numbers, eating away the wooden decking and other wooden objects such as furniture, panelling, doors and staircase banisters. When their food ran out they died, leaving behind calcareous tubes.[9]

The question of the victims' bodies is one that has often troubled explorers of the wreck site. When the debris field was surveyed in Robert Ballard's 1986 expedition, pairs of shoes were observed lying next to each other on the sea bed.[115] The flesh, bones, and clothes had long since been consumed but the tannin in the shoes' leather had apparently resisted the bacteria, leaving the shoes as the only markers of where a body had once lain.[9] Ballard has suggested that skeletons may remain deep within the Titanic's hull, such as in the engine rooms or third-class cabins. This has been disputed by scientists, who have estimated that the bodies would have completely disappeared by the early 1940s at the latest.[116]

The molluscs and scavengers did not consume everything organic. Some of the wooden objects on the ship and in the debris field have not been consumed, particularly those made of teak, a dense wood that seems to have resisted the borers.[117] The first-class reception area off the ship's Grand Staircase is still intact and furniture is still visible among the debris on the floor.[118] Although most of the corridors have lost their walls, furniture is still in place in many cabins; in one, a mattress is still on the bed, with an intact and undamaged dresser behind it.[119] Robert Ballard has suggested that areas within the ship or buried under debris, where scavengers may not have been able to reach, may still contain human remains.[120] According to Charles Pellegrino, who dived on the Titanic in 2001, a finger bone encircled by the partial remains of a wedding ring was found concreted to the bottom of a soup tureen that was retrieved from the debris field.[121] It was returned to the sea bed on the next dive.[122]

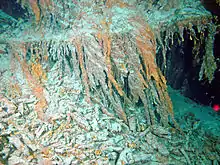

The longest-lasting inhabitants of the Titanic are likely to be bacteria and archaea that have colonised the metal hull of the ship. They have produced "reddish-brown stalactites of rust [hanging] down as much as several feet, looking like long needle-like icicles", as Ballard has put it. The formations, which Ballard dubbed "rusticles", are extremely fragile and disintegrate in a cloud of particles if touched.[123] The bacteria consume the iron in the hull, oxidising it and leaving rust particles behind as a waste product. To protect themselves from the seawater, they secrete an acidic viscous slime that flows where gravity takes it, carrying ferric oxides and hydroxides. These form the rusticles.[117]

When scientists were able to retrieve a rusticle, it was discovered that it was far more complex than had been imagined, with complex systems of roots infiltrating the metal, interior channels, bundles of fibres, pores and other structures. Charles Pellegrino comments that they seem more akin to "levels of tissue organization found in sponges or mosses and other members of the animal or plant kingdoms."[124] The bacteria are estimated to be consuming the Titanic's hull at the rate of 400 pounds (180 kg) per day, which is about 17 pounds (7.7 kg) per hour or 4+1⁄2 ounces (130 grams) per minute. Roy Collimore, a microbiologist, estimates that the bow alone now supports some 650 tons of rusticles,[107] and that they will have devoured 50% of the hull within 200 years.[106]

Since the Titanic's wreck was discovered in 1985, radical changes have been observed in the marine ecosystem around the ship. The 1996 expedition recorded 75% more brittle stars and sea cucumbers than Ballard's 1985 expedition, while crinoids and sea squirts had taken root all over the sea bed. Red krill had appeared, and an unknown organism had built numerous nests across the seabed from black pebbles. The number of rusticles on the ship had increased greatly. Curiously, the same thing had happened over about the same timescale to the wreck of the German battleship Bismarck, sunk at a depth of 4,791 metres (15,719 ft) on the other side of the Atlantic. The mud around the ship was found to contain hundreds of different species of animals. The sudden explosion of life around the Titanic may be a result of an increased amount of nutrients falling from the surface, possibly a result of human overfishing, eliminating fish that would otherwise have consumed the nutrients.[125]

Many scientists, including Ballard, are concerned that visits by tourists in submersibles and the recovery of artefacts are causing the wreck to decay faster. Underwater bacteria have been eating away at the Titanic's steel and transformed it into rust since the ship sank, but because of the extra damage caused by visitors, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimates that "the hull and structure of the ship may collapse to the ocean floor within the next 50 years."[126] The promenade deck has deteriorated significantly in recent years, partly because of damage caused by submersibles landing on the ship. The mast has almost completely deteriorated and has been stripped of its bell and brass light.

Other damage includes a gash on the bow section where block letters once spelled Titanic, part of the brass telemotor which once held the ship's wooden wheel is now twisted, and the crow's nest has completely deteriorated.[127] Cameron is responsible for some of the more significant damage during his expedition to the ship in 1995 to acquire footage for his film Titanic two years later. One of the MIR submersibles used on the expedition collided with the hull, damaging both and leaving fragments of the submersible's propeller shroud scattered around the superstructure. Captain Smith's quarters were heavily damaged by the collapse of the external bulkhead, which exposed the cabin's interior.[128]

In 2019 an international survey team reported that the wreck had further deteriorated and that the captain's bathtub was now lost.[129][130] A 2021 expedition reported that the tub was not lost but that the once clear view into it was obstructed by debris.[131]

Ownership

The Titanic's discovery in 1985 sparked a debate over the ownership of the wreck and the valuable items inside and on the sea bed around it. Ballard and his crew did not bring up any artefacts from the wreck, considering such an act to be tantamount to grave robbing. Ballard has since argued strongly "that it be left unmolested by treasure seekers".[132] As Ballard has put it, the development of deep-sea submersibles has made "the great pyramids of the deep .... accessible to man. He can either plunder them like the grave robbers of Egypt or protect them for the countless generations which will follow ours."[133] However, within only two weeks of the discovery, British insurance company the Liverpool and London Steamship Protection and Indemnity Association claimed that it owned the wreck, and several more schemes to raise it were announced.[134] A Belgian entrepreneur offered trips to the Titanic for $25,000 a head.[20] A British man named Douglas Faulkner-Woolley claims ownership of the Titanic, based on a "Late 1960s ruling" by the British Board of Trade which awarded him ownership of the wreck. The wreck had not been discovered at that time.[135]

Spurred by Ballard's appeals for the wreck to be left alone, North Carolina Congressman Walter B. Jones Sr. introduced the RMS Titanic Maritime Memorial Act in the United States House of Representatives in 1986. It called for strict scientific guidelines to be introduced to govern the exploration and salvage of the Titanic and urged the United States Secretary of State to lobby Canada, the United Kingdom and France to pass similar legislation. It passed the House and Senate by an overwhelming majority and was signed into law by President Ronald Reagan on 21 October 1986.[20] However, the law has been ineffective as the wreck lies outside United States waters, and the Act was set aside by the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, Norfolk Division, in 1998.[136] Although negotiations among the four countries were carried out between 1997 and 2000,[137] the resulting "Agreement Concerning the Shipwrecked Vessel RMS Titanic" has been ratified by only the US and the UK.[138]

Litigation and controversy

Only a few days after Ballard's discovery of the wreck, Jack Grimm—the author of the unsuccessful early 1980s attempts to find the Titanic—claimed ownership of it on the grounds that he had allegedly been the first to find it.[139] He announced that he intended to begin salvaging the wreck. He said that he "[couldn't] see them just lie there and be absorbed by the ocean floor. What possible harm can [salvaging] do to this mass of twisted steel?"[133]

Titanic Ventures Inc., a Connecticut-based consortium, co-sponsored a survey and salvage operation in 1987 with the French oceanographic agency IFREMER.[42] The expedition produced an outcry. Titanic survivor Eva Hart condemned what many saw as the looting of a mass grave: "To bring up those things from a mass sea grave just to make a few thousand pounds shows a dreadful insensitivity and greed. The grave should be left alone. They're simply going to do it as fortune hunters, vultures, pirates!"[140]

Public misgivings increased when, on 28 October 1987, a television program, Return to the Titanic Live, was broadcast from the Cité des Sciences et de l'Industrie in Paris, hosted by Telly Savalas.[140] In front of a live TV audience, a valise recovered from the sea bed was opened, revealing a number of personal items apparently belonging to Richard L. Beckwith of New York, who survived the sinking. A safe was also opened, revealing a few items of memorabilia and wet banknotes. The tone of the event was described by one commentator as "unsympathetic, lack[ing] dignity and finesse, and [with] all the superficial qualities of a 'media event'."[42]

New York Times television critic John Corry called the event "a combination of the sacred and profane and sometimes the downright silly".[141] Paul Heyer comments that it was "presented as a kind of deep sea striptease" and that Savalas "seemed haggard, missed several cues and at one point almost tripped over a chair". Controversy persisted after the broadcast when claims were made that the safe had been opened beforehand and that the show had been a fraud.[142]

Marex-Titanic Inc. was formed in 1992 to launch an expedition to the Titanic. Marex-Titanic's CEO was James Kollar. The company was a subsidiary of Marex International, an international marine salvage firm located in Memphis, Tennessee. In 1992 Marex made a bid to seize control of the artefacts and the wreck itself by suing Titanic Ventures, arguing that the latter had abandoned its claim by not returning to the wreck since the 1987 expedition. It claimed a superior right of salvage based on a "pill bottle" and hull fragment that were said to have been retrieved by Marex.[143] Marex simultaneously sent a vessel, the Sea Mussel, to carry out its own salvage operation.[144]

However, the Marex artefacts were alleged to have been illegally retrieved by the 1991 Russian-American-Canadian expedition[143] and Marex was issued with a temporary injunction preventing it from carrying out its plans. In October 1992 the injunction was made permanent and the salvage claims of Titanic Ventures were upheld.[145] The decision was later reversed by an appeals court but Marex's claims were not renewed.[143] Even so, Titanic Ventures' control of the artefacts recovered in 1987 remained in question until 1993 when a French administrator in the Office of Maritime Affairs of the Ministry of Equipment, Transportation, and Tourism awarded the company title to the artefacts.[146]

In May 1993, Titanic Ventures sold its interests in the salvage operations and artefacts to RMS Titanic Inc., a subsidiary of Premier Exhibitions Inc. headed by George Tulloch and Arnie Geller.[143] It had to go through a laborious legal process of having itself legally recognised as the sole and exclusive salvager of the wreck. Its claim was opposed for a while by the Liverpool and London Steamship Protection and Indemnity Association, the Titanic's former insurer, but was eventually settled. It was awarded ownership and salvaging rights by the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia on 7 June 1994 in a ruling that declared the company to be the "salvor in possession" of the wreck.[147]

Litigation has continued over the artefacts in recent years. In a motion filed on 12 February 2004, RMS Titanic Inc. requested that the United States district court enter an order awarding it "title to all the artefacts (including portions of the hull) which are the subject of this action pursuant to the Law of Finds" or, in the alternative, a salvage award in the amount of $225 million. RMS Titanic Inc. excluded from its motion any claim for an award of title to the objects recovered in 1987, but it did request that the district court declare that, based on the French administrative action, "the artifacts raised during the 1987 expedition are independently owned by RMST." Following a hearing, the district court entered an order dated 2 July 2004, in which it refused to grant comity or recognise the 1993 decision of the French administrator, and rejected RMS Titanic Inc.'s claim that it should be awarded title to the items recovered since 1993 under the Maritime Law of Finds.[148]

RMS Titanic Inc. appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. In its decision of 31 January 2006 the court recognised "explicitly the appropriateness of applying maritime salvage law to historic wrecks such as that of Titanic" and denied the application of the Maritime Law of Finds. The court also ruled that the district court lacked jurisdiction over the "1987 artifacts", and therefore vacated that part of the court's 2 July 2004 order. In other words, according to this decision, RMS Titanic Inc. has ownership title to the objects awarded in the French decision (valued $16.5 million earlier) and continues to be salvor-in-possession of the Titanic wreck. The Court of Appeals remanded the case to the District Court to determine the salvage award ($225 million requested by RMS Titanic Inc.).[149]

On 24 March 2009, it was revealed that the fate of 5,900 artefacts retrieved from the wreck would rest with a U.S. District Judge's decision.[150] The ruling was later issued in two decisions on 12 August 2010 and 15 August 2011. As announced in 2009, the judge ruled that RMS Titanic Inc. owned the artefacts and her decision dealt with the status of the wreck as well as establishing a monitoring system to check future activity upon the wreck site.[151] On 12 August 2010, Judge Rebecca Beach Smith granted RMS Titanic, Inc. fair market value for the artefacts but deferred ruling on their ownership and the conditions for their preservation, possible disposition and exhibition until a further decision could be reached.[152]

On 15 August 2011, Judge Smith granted title to thousands of artefacts from the Titanic, that RMS Titanic Inc. did not already own under a French court decision concerning the first group of salvaged artefacts, to RMS Titanic Inc. subject to a detailed list of conditions concerning preservation and disposition of the items.[153] The artefacts can be sold only to a company that would abide by the lengthy list of conditions and restrictions.[153] RMS Titanic Inc. can profit from the artefacts through exhibiting them.[153]

RMS Titanic Inc. has also attempted to secure exclusive physical access to the wreck site. In 1996, it obtained a court order finding that it had "the exclusive right to take any and all types of photographic images of the Titanic wreck and wreck site." It obtained another order in 1998 against Deep Ocean Expeditions and Chris Haver, a British Virgin Islands corporation that aimed to run tourist trips to the Titanic at a cost of $32,000 per person[154] (it now charges $60,000[155]). This was overturned in March 1999 by the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, which ruled that the law of salvage did not extend to obtaining exclusive rights to view, visit and photograph a wreck.

The court pointed out that the Titanic is "located in a public place" in international waters, rather than in a private or controllable location to which access could be restricted by the owner. Granting such a right would also create a perverse incentive; since the aim of salvage is to carry out a salvage operation, leaving property in place so that it could be photographed would run counter to this objective.[156]

Conservation issues

RMS Titanic Inc. has attracted considerable controversy for its approach to the Titanic. Two rival camps have formed following the wreck's discovery: the "conservationists", championed by RMS Titanic Inc.'s George Tulloch (who died in 2004), and the "protectionists", whose most prominent advocate is Robert Ballard. The first camp has argued that artefacts from around the wreck should be recovered and conserved, while the latter camp argues that the entire wreck site should have been left undisturbed as a mass grave. Both camps agree that the wreck itself should not be salvaged – though RMS Titanic Inc. did not stick to its proclaimed "hands-off" policy when it managed to demolish the Titanic's crow's nest in the course of retrieving the bell.[47] Its predecessor Titanic Ventures agreed with IFREMER that it would not sell any of the artefacts but would put them on public display, for which it could charge an entry fee.[157]

Tulloch's approach has undoubtedly resulted in outcomes that would not have been possible otherwise. In 1991, he presented Edith Brown Haisman, a 96-year-old survivor of the disaster, with her father's pocket watch, which had been retrieved from the sea bed. She had last seen it on 15 April 1912, when he waved goodbye to his wife and daughter as they left aboard lifeboat 14. They never saw him again, and he presumably went down with the ship.[158] The watch was loaned to Haisman "for life"; when she died five years later, it was reclaimed by RMS Titanic Inc.[159]

On another occasion, a steamer trunk spotted in the debris field was found to contain three musical instruments, a deck of playing cards, a diary belonging to one Howard Irwin, and a bundle of letters from his girlfriend Pearl Shuttle.[160] It was first thought that Irwin, a musician and professional gambler, had boarded the ship under a false identity. There was no record of him being among the passengers, even though a ticket had been purchased for him. It turned out that he had stayed ashore but his trunk had been brought aboard the ship by his friend Henry Sutehall, who was among the victims of the disaster.[161] The fragile contents of the trunk were preserved by the interior's starvation of oxygen, which prevented bacteria from consuming the paper. Very few other shipwrecks have yielded readable paper.[162]

On the other hand, the heavily commercialised approach of RMS Titanic Inc. has caused repeated controversy and many have argued that salvaging the Titanic is an inherently disrespectful act. The wreck site has been called a "tomb and a reliquary", a "gravestone for the 1,500 people who died" and "hallowed ground".[163] Titanic historians John Eaton and Charles Haas argue that the salvagers are little more than "plunderers and armchair salvage experts" and others have characterised them as "grave robbers".[164] The Return to Titanic... Live! television show in 1987 was widely condemned as a "circus",[165] though the 1987 expedition's scientific and financial leaders had no control over the show.[42]

In a particularly controversial episode, RMS Titanic Inc. sold some 80,000 lumps of coal retrieved from the debris field in order to fund the rumoured $17 million cost of lifting the "Big Piece" of the ship's hull.[47] It attempted to get around the no-sale agreement with IFREMER by charging the new owners a $25 "fee" to act as "conservators", in order to claim that the coal lumps had not actually been sold.[165] This attracted strong criticism from all sides.[47] Nonetheless, in 1999 Tulloch was ousted by the company's shareholders and was replaced by Arnie Geller, who promised a more aggressive approach to making a profit. The company declared that it had an "absolute right" to sell recovered gold, coins and currency. It was prevented from doing this by a court order in the United States and IFREMER withdrew its co-operation and its submersibles, threatening a lawsuit.[165]

UK and US protection agreement

In January 2020, the United Kingdom and United States governments announced that they had agreed to protect the wreckage of the Titanic. The agreement, signed by the British government in 2003, came into effect after being ratified by U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo at the end of 2019. UK Maritime Minister Nus Ghani said the UK would work with Canada and France to bring "even more protection" to the wreckage.[166]

Exhibitions of Titanic artefacts

Artefacts

Objects from the Titanic have been exhibited for many years, though only a few were retrieved before the discovery of the wreck in 1985. The Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax, Nova Scotia, has a collection of wooden fragments and an intact deckchair plucked from the sea by the Canadian search vessels that recovered the victims' bodies.[167] Various other museums, including the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich and the SeaCity Museum in Southampton, have objects donated by survivors and relatives of victims, including some items that were retrieved from the bodies of victims.

More donated Titanic artefacts are to be found in the Merseyside Maritime Museum in Liverpool and the Titanic Historical Society's museum in Indian Orchard, Springfield, Massachusetts.[168] The latter's collection includes items such as the life jacket of Madeleine Astor, the wife of millionaire Titanic victim John Jacob Astor IV, a rivet which was removed from the hull before the Titanic went to sea, an ice warning which never reached the bridge, a restaurant menu and a sample square of carpet from a First Class stateroom.[169]

Exhibitions

RMS Titanic Inc. organises large-scale exhibitions around the world of artefacts retrieved from the wreck site. After minor exhibitions were held in Paris and Scandinavia, the first major exhibition of recovered artefacts was held at the National Maritime Museum in 1994–95.[170] It was hugely popular, drawing an average of 21,000 visitors a week during the year-long exhibition.[171] Since then, RMS Titanic Inc. has established a large-scale permanent exhibition of Titanic artefacts at the Luxor hotel and casino in Las Vegas, Nevada.

The 25,000-square-foot (2,300-square-metre) exhibit is the home of the "Big Piece" of the hull retrieved in 1998 and features conserved items including luggage, the Titanic's whistles, floor tiles and an unopened bottle of champagne.[172] The exhibit includes a full-scale replica of the ship's Grand Staircase and part of the Promenade Deck, and even a mock-up of the iceberg. It also runs a travelling exhibition called Titanic: The Artifact Exhibition which has opened in various cities around the world and has been seen by over 20 million people. The exhibition typically runs for six to nine months featuring a combination of artefacts, reconstructions and displays of the ship, her passengers and crew and the disaster itself. In a similar fashion to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., visitors are given a "boarding pass" in the name of an individual passenger at the start of the exhibition. They do not discover the fate of their assigned passenger until the end.[173]

Ownership

The vast majority of the relics retrieved by various groups from the Titanic were owned by Premier Exhibitions which operated RMS Titanic Inc. and filed for bankruptcy in 2016. In late August 2018, the groups vying to purchase the 5,500 relics included one by museums in England and Northern Ireland, with assistance from James Cameron and some financial support from National Geographic. Oceanographer Robert Ballard said he favoured this bid since it would ensure that the memorabilia would be permanently displayed in Belfast and in Greenwich. A decision as to the outcome was to be made by a United States district court judge in the case titled RMS Titanic Inc., 16-02230, U.S. Bankruptcy Court, Middle District of Florida (Jacksonville).[174][175] On 18 October 2018, a judge approved the sale of artefacts to a private investor group.[176]

See also

- The Big Piece, the largest piece of the Titanic's wreck to be discovered

- RMS Titanic Maritime Memorial Act

- Agreement Concerning the Shipwrecked Vessel RMS Titanic

- International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea

- List of archaeological sites beyond national boundaries

Footnotes

- ↑ Ballard 1987, p. 249: The coordinates are the centre of the boiler field.

- 1 2 Serway & Jewett 2006, p. 494.

- 1 2 3 Lord 1987, p. 231.

- 1 2 New Scientist 1977.

- ↑ Eaton & Haas 1987, p. 130.

- ↑ Wade 1992, p. 72.

- ↑ Little 2010.

- ↑ Estes 2006, p. 298.

- 1 2 3 4 Ballard 1987, p. 207.

- ↑ Lord 1987, p. 226.

- ↑ Lord 1987, p. 227.

- 1 2 3 4 Eaton & Haas 1987, p. 132.

- ↑ Eaton & Haas 1994, p. 302.

- ↑ Lord 1987, pp. 230–231.

- ↑ Suid 1996, p. 210.

- ↑ Hicks & Kropf 2002, p. 194.

- 1 2 Ballard 1987, p. 38.

- ↑ Time 1981.

- ↑ Eaton & Haas 1994, p. 304.

- 1 2 3 Eaton & Haas 1987, p. 137.

- ↑ Lord 1987, pp. 232–233.

- 1 2 Ballard 1987, p. 47.

- 1 2 Maxa, Kathleen (21 June 1981). "The Texas Tycoon in Search of the Titanic". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ↑ Ballard 1987, p. 50.

- 1 2 3 4 Ballard 1987, p. 51.

- ↑ Ballard 1987, p. 49.

- ↑ Ballard 1987, p. 53.

- ↑ Ballard 2008, p. 100.

- ↑ Ballard & Hively 2002, p. 235.

- 1 2 Ballard 2008, p. 97.

- ↑ Ballard & Hively 2002, p. 225.

- ↑ Ballard & Hively 2002, p. 239.

- ↑ Ballard 2008, p. 98.

- ↑ Ballard 2008, p. 101.

- ↑ Ballard 1987, p. 66.

- ↑ Ballard & Hively 2002, p. 250.

- ↑ Ballard 1987, p. 82.

- ↑ Ballard 1987, p. 88.

- ↑ Ballard 1987, p. 98.

- ↑ Eaton & Haas 1994, p. 309.

- ↑ Lynch 1992, p. 207.

- 1 2 3 4 Eaton & Haas 1994, p. 310.

- ↑ Eaton & Haas 1994, pp. 312–313.

- ↑ Lynch 1992, p. 209.

- ↑ Eaton & Haas 1994, pp. 314–316.

- ↑ Eaton & Haas 1994, p. 324.

- 1 2 3 4 Butler 1998, p. 216.

- 1 2 3 "Titanic emotions come to the surface". The Irish Times. Irish Times Trust. 15 August 1998. Archived from the original on 29 September 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Titanic salvage hits storm of protest". BBC News. BBC. 14 August 1998. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ↑ Spignesi 2012, p. 254.

- ↑ Spignesi 2012, p. 277.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Brace, Matthew (30 August 1996). "Real-life drama unfolds as Titanic raised after 84 years". The Independent. Independent Digital News & Media Ltd. Archived from the original on 7 May 2022.

- 1 2 "Cruise Ships Sail To Site Of Titanic". The Spokseman-Review. Cowles Company. 26 August 1996. Archived from the original on 17 April 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Attempt to Salvage Part of the Titanic Runs Aground". Los Angeles Times. 31 August 1996. Archived from the original on 5 November 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ringle, Ken (6 August 1996). "New Depths for Titanic Promoter?". The Washington Post. Nash Holdings. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 Broad, William J. (31 August 1996). "Effort to Raise Part of Titanic Falters as Sea Keeps History". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 April 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- 1 2 3 "21-Ton Chunk of Titanic Sinks Again". AP News. Associated Press. 30 August 1996. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ↑ Butler 1998, pp. 217–218.

- ↑ Spignesi 2012, p. 258.

- ↑ MacInnis & Cameron 2005, p. 23.

- ↑ Parisi 1998, p. 8.

- ↑ Timeline for 2000.

- ↑ "Titanic couple take the plunge". BBC News. BBC. 28 July 2001. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ↑ Spignesi 2012, p. 239.

- 1 2 Timeline for 2001.

- ↑ NOAA 2003.

- ↑ NOAA 2004.

- ↑ Timeline for 2004.

- ↑ Canfield 2012.

- ↑ Symonds 2012.

- ↑ "The wreck of the Titanic now protected by UNESCO". UNESCO. 5 April 2012. Archived from the original on 14 April 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ↑ Sides, Hampton (April 2012). "Unseen Titanic". National Geographic. 221 (4): 95. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ↑ "First dive to Titanic in 14 years shows wreck is deteriorating". BNO News. 21 August 2019. Archived from the original on 23 August 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ↑ "Back to the Titanic". Disney+ Hotstar. Archived from the original on 12 October 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ↑ Morelle, Rebecca; Francis, Alison (17 May 2023). "Titanic: First ever full-sized scans reveal wreck as never seen before". bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 17 May 2023.

- ↑ "OceanGate sub makes first dive to Titanic wreck site and captures photos of debris". GeekWire. 13 July 2021. Archived from the original on 19 June 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ↑ Patil, Anushka (22 June 2023). "The debris found today was "consistent with catastrophic loss of the pressure chamber" in the submersible, Mauger said". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ↑ Perrottet, Tony (June 2019). "A Deep Dive Into the Plans to Take Tourists to the 'Titanic'". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ↑ Amos, Jonathan (20 June 2023). "Titanic sub live updates: Crew of Titan sub believed to be dead, says vessel operator". BBC News. Archived from the original on 22 June 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ↑ Gibson 2012, p. 240.

- ↑ Halpern & Weeks 2011, p. 126.

- 1 2 3 Ballard 1987, p. 204.

- 1 2 Halpern & Weeks 2011, p. 127.

- 1 2 Lynch 1992, p. 205.

- ↑ "Unseen Titanic – Interactive: The Crash Scene". National Geographic. 17 October 2002. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ↑ Ballard 1987, p. 206.

- ↑ Pellegrino 2012, pp. 100–101.

- 1 2 3 4 Gannon 1995.

- ↑ Lynch & Marschall 2003, p. 58.

- ↑ Marschall 2001, p. 3.

- ↑ Stephenson 2005.

- ↑ Ballard 1988, p. 47.

- ↑ Lynch & Marschall 2003, pp. 119–120.

- ↑ "Full Titanic site mapped for first time". USA Today. Gannett Company. Associated Press. 8 March 2012. Archived from the original on 13 April 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ↑ Pellegrino 2012, p. 107.

- 1 2 Pellegrino 2012, p. 108.

- 1 2 Halpern & Weeks 2011, p. 128.

- ↑ Ballard 1987, p. 202.

- 1 2 3 Cohen 2012.

- ↑ Ballard 1987, p. 190.

- ↑ Rubin, Sydney (1987). "Treasures of the Titanic". Popular Mechanics. New York: Hearst Magazines. 164 (12): 65–69. ISSN 0032-4558. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ↑ Ballard 1987, p. 150.

- ↑ Ballard 1987, p. 203.

- ↑ Butler 1998, p. 214.

- 1 2 3 Mone 2004.

- 1 2 3 Handwerk 2010.

- ↑ Broad 1995.

- ↑ Pellegrino 2012, p. 83.

- ↑ Pellegrino 2012, p. 274.

- ↑ BBC News 2010.

- ↑ Augenstein, Seth (6 September 2016). "'Extremophile Bacteria' Will Eat Away Wreck of the Titanic by 2030". Laboratory Equipment. CompareNetworks. Archived from the original on 7 September 2016.

- ↑ NewsCore (8 January 2015). "Titanic Wreck Being Eaten by Superbug, Will Disappear in 20 Years". Fox News. FOX News Network, LLC. Archived from the original on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ↑ Fox-Skelly, Jasmin (5 February 2018). "The wreck of the Titanic is being eaten and may soon vanish". BBC Earth. BBC. Archived from the original on 23 April 2018. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- ↑ Ballard 1987, p. 192.

- ↑ Spignesi 2012, p. 242.

- 1 2 Ballard 1987, p. 208.

- ↑ Pellegrino 2012, p. 84.

- ↑ Pellegrino 2012, p. 102.

- ↑ Spignesi 2012, p. 240.

- ↑ Pellegrino 2012, p. 198.

- ↑ Pellegrino 2012, p. 199.

- ↑ Ballard 1987, p. 122.

- ↑ Pellegrino 2012, p. 200.

- ↑ Pellegrino 2012, pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Crosbie & Mortimer 2006, p. last page (no page number specified).

- ↑ Ballard 2004.

- ↑ Eaton & Haas 1999, p. 205.

- ↑ Morelle, Rebecca (21 August 2019). "Titanic sub dive reveals parts are being lost to sea". BBC News. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ↑ Webster, Ben. "Titanic dive: Captain's bath lost for ever as ocean eats away at wreck". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Archived from the original on 21 May 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ↑ Hurley, Bevan (18 October 2021). "Titanic's famous captain's bathtub reappears, as wreck's rapid disintegration revealed in new footage". Independent. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ↑ Lynch 1992, p. 13.

- 1 2 Eaton & Haas 1987, p. 148.

- ↑ R.M.S. Titanic, Inc., etc. v. The Wrecked And Abandoned Vessel, Its Engines, Tackle, Apparel, Appurtenances, Cargo, Etc., Located Within One (1) Nautical Mile Of A Point Located At 41 43 32 North Latitude And 49 56 49 West Longitude, Believed To Be The R.M.S. Titanic, 2:93-cv-00902, (E.D. Va.)

- ↑ Spignesi, Stephen (20 February 2012). "An Expanded Interview with Douglas Faulkner-Woolley". Stephen Spignesi. Archived from the original on 28 March 2022. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ↑ For an overall discussion of the history of the salvage legal proceedings, see R.M.S. Titanic, Inc. v. Haver, 171 F.3d 943 (4th Cir. Va. 1999), and related opinions.

- ↑ Scovazzi 2003, p. 64.

- ↑ NOAA 2012.

- ↑ Ferguson 1985.

- 1 2 Lynch 1992, p. 208.

- ↑ Eaton & Haas 1999, p. 195.

- ↑ Heyer 1995, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 4 Eaton & Haas 1994, p. 313.

- ↑ Associated Press 1992.

- ↑ Taylor 1992.

- ↑ "RMS Titanic Maritime Memorial of Preservation Act of 2007" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- ↑ Scovazzi 2003, pp. 65–66.

- ↑ "Salvage Law Update Fall 2004" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ↑ "United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, R.M.S. Titanic, Incorporated vs. The Wrecked and Abandoned Vessel – 31 January 2006" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 September 2011. Retrieved 3 September 2011. ( 127 KiB )

- ↑ White, Marcia (24 March 2009). "Battle continues on fate of relics from doomed ship Titanic". The Express-Times. Archived from the original on 23 February 2012. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- ↑ "Federal judge to rule on fate of Titanic artifacts". USA Today. 24 March 2009. Archived from the original on 22 April 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- ↑ McGlone, Tim (14 August 2010). "Norfolk judge grants salvage award for Titanic artifacts". The Virginian-Pilot. Archived from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- 1 2 3 McGlone, Tim (16 August 2011). "Norfolk judge awards rights to Titanic artifacts". The Virginian-Pilot. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- ↑ Scovazzi 2003, p. 67.

- ↑ Spignesi 2012, p. 260.

- ↑ Scovazzi 2003, p. 68.

- ↑ Riding 1992.

- ↑ Butler 1998, p. 218.

- ↑ Jorgensen-Earp 2006, p. 62.

- ↑ Pellegrino 2012, p. 207.

- ↑ Pellegrino 2012, p. 209.

- ↑ Pellegrino 2012, p. 205.

- ↑ Jorgensen-Earp 2006, p. 45.

- ↑ Jorgensen-Earp 2006, p. 46.

- 1 2 3 Jorgensen-Earp 2006, p. 48.

- ↑ "RMS Titanic wreck to be protected under UK and US agreement". BBC News. BBC. 21 January 2020. Archived from the original on 22 January 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ↑ Lynch 1992, pp. 178–179.

- ↑ Ward 2012, pp. 248, 251.

- ↑ Kelly 2009.

- ↑ Portman 1994.

- ↑ Stearns 1995.

- ↑ Spignesi 2012, p. 259.

- ↑ Ward 2012, pp. 252–253.

- ↑ "Florida Middle Bankruptcy Court Case 3:16-bk-02230 – RMS Titanic, Inc. -". app.courtdrive.com. Archived from the original on 2 September 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ↑ Dawn McCarty; Jef Feeley; Chris Dixon (31 August 2018). "Bankrupt Titanic exhibitor sets biggest sale of ship relics". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 2 September 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ↑ Alicia McElhaney (22 October 2018). "Investor Group Including Apollo Acquires Titanic Artifacts". Institutional Investor. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

Sources

Books

- Ballard, Robert D. (1987). The Discovery of the Titanic. New York: Warner Books. ISBN 978-0-446-51385-2.

- Ballard, Robert (1988). Exploring the Titanic. New York: Scholastic. ISBN 0590419528.

- Ballard, Robert D.; Hively, Will (2002). The Eternal Darkness: A Personal History of Deep-Sea Exploration. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09554-7.

- Ballard, Robert D. (2008). Archaeological Oceanography. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12940-2.

- Butler, Daniel Allen (1998). Unsinkable: The Full Story of RMS Titanic. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-1814-1.

- Crosbie, Duncan; Mortimer, Sheila (2006). Titanic: The Ship of Dreams. New York, NY: Orchard Books. ISBN 978-0-439-89995-6.

- Eaton, John P.; Haas, Charles A. (1987). Titanic: Destination Disaster: The Legends and the Reality. Wellingborough, UK: Patrick Stephens. ISBN 978-0-85059-868-1.

- Eaton, John P.; Haas, Charles A. (1999). Titanic: A Journey Through Time. Sparkford, Somerset: Patrick Stephens. ISBN 978-1-85260-575-9.