| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

9H-Xanthen-9-one | |

| Other names

9-Oxoxanthene Diphenyline ketone oxide | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| 140443 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.001.816 |

| EC Number |

|

| 166003 | |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

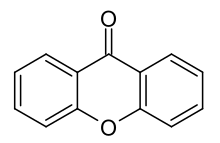

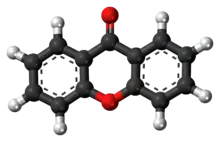

| C13H8O2 | |

| Molar mass | 196.205 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | white solid |

| Melting point | 174 °C (345 °F; 447 K) |

| Sl. sol. in hot water | |

| -108.1·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling:[1] | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H301 | |

| P264, P270, P301+P310, P321, P330, P405, P501 | |

| Related compounds | |

Related compounds |

xanthene |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Xanthone is an organic compound with the molecular formula O[C6H4]2CO. It is a white solid.

In 1939, xanthone was introduced as an insecticide and it currently finds uses as ovicide for codling moth eggs and as a larvicide.[2] Xanthone is also used in the preparation of xanthydrol, which is used in the determination of urea levels in the blood.[3] It can also be used as a photocatalyst.[4]

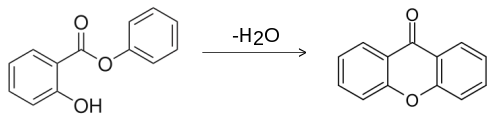

Synthesis

Xanthone can be prepared by the heating of phenyl salicylate:[5]

Six methods have been reported for synthesizing xanthone derivatives:[6]

- The Michael-Kostanecki method uses an equimolar mix of a polyphenol and an O-hydroxybenzoic acid, which are heated with a dehydrating agent.

- The Friedel-Crafts method has a benzophenone intermediate.

- The Robinson-Nishikawa method is a variant of the Hoesch synthesis but with low yields.

- The Asahina-Tanase method synthesizes some methoxylated xanthones, and xanthones with acid-sensitive substituents.

- The Tanase method is used to synthesize polyhydroxyxanthones.

- The Ullman method condenses a phenol with an O-chlorobenzene and cyclizes the resulting diphenylether.

Xanthone derivatives

Xanthone forms the core of a variety of natural products, such as mangostin or lichexanthone. These compounds are sometimes referred to as xanthones or xanthonoids. Over 200 natural xanthones have been identified. Many are phytochemicals found in plants in the families Bonnetiaceae, Clusiaceae, and Podostemaceae.[7] They are also found in some species of the genus Iris.[8] Some xanthones are found in the pericarp of the mangosteen fruit (Garcinia mangostana) as well as in the bark and timber of Mesua thwaitesii.[9]

- Bone fide agents include AH 7614 & TUG-1387.[10]

See also

References

- ↑ "Xanthone". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- ↑ Steiner, L. F. and S. A. Summerland. 1943. Xanthone as an ovicide and larvicide for the codling moth. Journal of Economic Entomology 36, 435-439.

- ↑ Bowden, R. S. T. (1962). "The Estimation of Blood Urea by the Xanthydrol Reaction". Journal of Small Animal Practice. 3 (4): 217–218. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5827.1962.tb04191.x.

- ↑ Romero, Nathan A.; Nicewicz, David A. (10 June 2016). "Organic Photoredox Catalysis". Chemical Reviews. 116 (17): 10075–10166. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00057. PMID 27285582.

- ↑ A. F. Holleman (1927). "Xanthone". Org. Synth. 7: 84. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.007.0084.

- ↑ Diderot, Noungoue Tchamo; Silvere, Ngouela; Etienne, Tsamo (2006). "Xanthones as therapeutic agents: chemistry and pharmacology". In Khan, M.T.H.; Ather, A. (eds.). Lead Molecules from Natural Products: Discovery and New Trends. Advances in Phytomedicine. Elsevier Science. pp. 284–285. ISBN 978-0-08-045933-2.

- ↑ "An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG II". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 141 (4): 399–436. 2003. doi:10.1046/j.1095-8339.2003.t01-1-00158.x.

- ↑ Williams, C.A; Harborne, J.B.; Colasante, M. (2000). "The pathway of chemical evolution in bearded iris species based on flavonoid and xanthone patterns" (PDF). Annali di Botanica. 58: 51–54. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ↑ Bandaranayake, Wickramasinghe M.; Selliah, Sathiaderan S.; Sultanbawa, M.Uvais S.; Games, D.E. (1975). "Xanthones and 4-phenylcoumarins of Mesua thwaitesii". Phytochemistry. 14: 265–269. doi:10.1016/0031-9422(75)85052-7.

- ↑ Watterson, Kenneth R.; Hansen, Steffen V. F.; Hudson, Brian D.; Alvarez-Curto, Elisa; Raihan, Sheikh Zahir; Azevedo, Carlos M. G.; Martin, Gabriel; Dunlop, Julia; Yarwood, Stephen J.; Ulven, Trond; Milligan, Graeme (2017). "Probe-Dependent Negative Allosteric Modulators of the Long-Chain Free Fatty Acid Receptor FFA4". Molecular Pharmacology. 91 (6): 630–641. doi:10.1124/mol.116.107821. ISSN 0026-895X. PMC 5438128. PMID 28385906.