| Yangtze Patrol | |

|---|---|

USS Panay, a United States Navy river gunboat, of the "Yangtze Patrol" commissioned in 1928, as she sinks on the Yangtze River near Nanking, China in December 1937, after being attacked by Japanese aircraft. | |

| Planned by | |

| Objective | protect U.S. interests and citizens in Yangtze River treaty ports in Qing Empire from Chinese insurgents and river pirates |

| Date | 1854–1949 |

| Executed by | United States Navy |

| Outcome | avoided internal Chinese conflicts in mid-19th to mid-20th century, except for World War II |

The Yangtze Patrol, also known as the Yangtze River Patrol Force, Yangtze River Patrol, YangPat and ComYangPat, was a prolonged naval operation from 1854 to 1949 to protect American interests in the Yangtze River's treaty ports. The Yangtze Patrol also patrolled the coastal waters of China where they protected U.S. citizens, their property, and Christian missionaries.

The Yangtze River is the longest river in China, and it plays an important commercial role, with ocean-bound vessels proceeding as far upstream as the city of Wuhan. This squadron-sized unit cruised the waters of the Yangtze from Shanghai on the Pacific Ocean into the far interior of China at Chongqing.[1]

Initially, the Yangtze Patrol was formed from ships of the United States Navy and assigned to the East India Squadron. In 1868, patrol duties were carried out by the Asiatic Squadron of the United States Navy. Under the unequal treaties, the United States, Japan, and various European powers, especially the United Kingdom, which had been on the Yangtze since 1897, were allowed to cruise China's rivers.

In 1902, the United States Asiatic Fleet took control of the operations of the Yangtze Patrol.

In 1922, Yangtze Patrol was established as a formal component of the United States Navy in China.

In 1942, at the beginning of World War II, the Yangtze Patrol effectively ceased operations in China because of the limited resources of the United States Navy, which needed the patrol crews and their ships elsewhere in fighting Japanese forces throughout the Pacific.

Following the end of World War II, the Yangtze Patrol resumed its duties in 1945, but on a more limited basis with fewer ships during the Chinese Civil War. When the Chinese Communist forces eventually occupied the Yangtze River valley in 1949, the United States Navy permanently ceased operations and disbanded the Yangtze Patrol.

Operations (1854–1949)

19th century

1854–1860

As a result of treaties imposed on China by foreign powers after the First (1839–1842) and Second Opium Wars (1856–1860), China was opened to foreign trade at a number of locations known as "treaty ports" where foreigners were permitted to live and conduct business. Also, created by the treaties was the doctrine of extraterritoriality, a system whereby citizens of foreign countries living in China were subject to the laws of their home country. Most favoured nation treatment under the treaties assured other countries of the fact that the same privileges would be afforded to them as well, and soon many nations, including the United States, operated merchant ships and navy gunboats on the waterways of China.

1860–1900

During the 1860s and 1870s, American merchant ships were prominent on the lower Yangtze River, operating up to the deepwater port of Hankow 680 mi (1,090 km) inland. The added mission of anti-piracy patrols required U.S. naval and marine landing parties be put ashore several times to protect American interests. In 1874, the U.S. gunboat, USS Ashuelot, reached as far as Ichang, at the foot of the Yangtze gorges, 975 miles (1,569 km) from the sea. During this period, most US personnel found a tour in the Yangtze to be uneventful, as a major American shipping company had sold its interests to a Chinese firm, leaving the patrol with little to protect. However, as the stability of China began to deteriorate after 1890, the U.S. naval presence began to increase along the Yangtze.[2]

20th century

1900–1920

In 1901, American-flagged merchant vessels returned to the Yangtze when Standard Oil Company placed a steam-powered tanker in service on the lower river. Within the decade, several small motorships began hauling kerosene, the principal petroleum product used in China for that company. At the same time, the United States Navy acquired four Spanish vessels (the gunboats USS Elcano, Quiros, Villalobos , and Callao), which it had seized in the Philippines during the Spanish–American War. These vessels became the core of the Yangtze River patrol for the first dozen years of the 20th century, but they lacked the power to go beyond Yichang onto the more difficult stretches of the river.

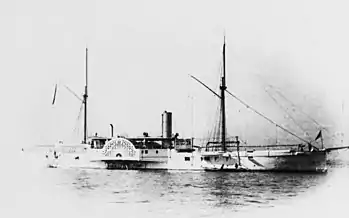

USS Palos and Monocacy were the first American gunboats built specifically for service on the Yangtze River. The Mare Island Naval Shipyard in Vallejo, California built them in 1913. The U.S. Navy then had them disassembled and shipped to China aboard the American steamer Mongolia. The Jiangnan Shipyard in Shanghai reassembled them and put them into service in 1914.

Later in 1914, both vessels demonstrated their ability to handle the rapids of the upper river when they reached Chongqing, which was more than 1,300 mi (2,100 km) from the sea, and then went further to Jiading on the Min River. In 1917, the U.S. entered World War I. The U.S. rendered the guns of Palos and Monocacy inoperable to protect Chinese neutrality. After China entered the war on the side of the Allies, the U.S. Navy reactivated the guns.

In 1917, the first Standard Oil tanker reached Chongqing, and a pattern of American commerce on the river began to emerge. On 17 January 1918, armed Chinese men attacked Monocacy and she was forced to return fire with her 6-pounder gun. Passenger and cargo service by American-flag ships began in 1920 with the Robert Dollar Line and the American West China Company. They were followed in 1923 by the Yangtze River Steamship Company, which stayed on the river until 1935, long after the other American passenger-cargo ships were gone.

1920–1930

In the early 1920s, the patrol found itself fighting the forces of warlords and bandits. To accommodate its increased responsibilities on the river, the United States Navy constructed six new gunboats in Shanghai during 1926–1927 and commissioned them in late 1927–1928 during the command of Rear Admiral Yates Stirling Jr. to replace four craft, originally seized from Spain during the Spanish–American War, that had been patrolling since 1903. All were capable of reaching Chongqing at high water, and all year-round. Collectively referred to by the U.S. press as "the new six", USS Luzon and Mindanao were the largest, USS Oahu and Panay next in size, and USS Guam and Tutuila the smallest. These vessels gave the Navy the capability it needed at a time when operational requirements were growing rapidly.

In the late 1920s, Chiang Kai-shek and the Northern Expedition created a volatile military situation for the patrol along the Yangtze.

1930–1942

After the Japanese took control of much of the middle and lower Yangtze in the 1930s, American river gunboats entered into a period of inactivity and impotence. During the early-1930s, National Revolutionary Army took control of much of the north bank of the middle river. The climax of hostilities occurred in 1937 with the Rape of Nanking and the sinking of Panay by the Japanese. The USS Panay incident was the first loss of a U.S. Navy vessel in the conflict which would soon become World War II.[3] Just prior to the Attack on Pearl Harbor, most of the ships on the Yangtze River Patrol were brought out of China, with only the smallest gunboats, Wake (the renamed Guam) and Tutuila remaining behind. Wake, at Shanghai, was subsequently captured by the Japanese. Tutuila, at Chongqing, was turned over to the Chinese. When the other gunboats reached Manila, the Yangtze River Patrol was formally dissolved when, on 5 December 1941, Rear Admiral Glassford sent the message, "COMYANGPAT DISSOLVED". Subsequently, the evacuated ships were all scuttled or captured with their crews and imprisoned by the Japanese, after the fall of Corregidor in mid-1942. Luzon was later salvaged and used by the Japanese. USS Asheville was sunk in battle on 3 March 1942 and Mindanao was scuttled on 2 May; Oahu was sunk in battle 5 May 1942.

During different periods of time, Naval and Marine Corps personnel, who were in the patrol, were eligible for either the Yangtze Service Medal or the China Service Medal.

1945–1949

After the surrender of Japan, some patrols on the river were resumed in September 1945. A few days after Japan's surrender, Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid, commander of the United States 7th Fleet, sailed south aboard USS Rocky Mount to rendezvous with Task Force 73 and continue on to Shanghai. However, they were delayed due to a large typhoon and the river being swept for mines. They finally proceeded up the river and arrived in Shanghai on 19 September 1945, with the first Allied ships in over three years. The American flotilla included the command ship (USS Rocky Mount), two light cruisers, four destroyers, twelve destroyer escorts, and many PT boats and minesweepers along with a British naval contingent of three light cruisers, six destroyers, six destroyer escorts, and some minesweepers. In November the new heavy cruiser USS St. Paul joined the unit.

When the Chinese Civil War finally reached the Yangtze Valley, in 1949, the U.S. Navy permanently ceased operations on the Yangtze River and officially disbanded the Yangtze Patrol.

Yangtze River Patrol gunboats

USS Yantic (1874)

USS Yantic (1874).jpg.webp) USS Elcano (1902-1928)

USS Elcano (1902-1928)_at_Hangzhou%252C_China%252C_during_the_1920s_(NH_67127).jpg.webp) USS Villalobos (1903-1928)

USS Villalobos (1903-1928)_at_Nanking%252C_China%252C_in_1932_(NH_68196).jpg.webp) USS Monocacy (1914-1939)

USS Monocacy (1914-1939).jpg.webp) USS Penguin (1923-1941)

USS Penguin (1923-1941)_at_anchor_in_the_Panama_Canal_Zone%252C_circa_in_the_1920s_(80-G-1034878).jpg.webp) USS Asheville (1926-1927)

USS Asheville (1926-1927) USS Palos (1926)

USS Palos (1926)_docked_in_China%252C_in_the_1930s.jpg.webp) USS Luzon (1927-1942)

USS Luzon (1927-1942)_at_Chungking%252C_China%252C_during_a_bombing_raid%252C_circa_in_1938.jpg.webp) USS Tutuila (1928-1937)

USS Tutuila (1928-1937)_in_port%252C_in_the_1930s_(NH_60512).jpg.webp) USS Mindanao (1928-1941)

USS Mindanao (1928-1941).png.webp) USS Tulsa (1929-1941)

USS Tulsa (1929-1941)_in_the_1930s_(NH_44570).jpg.webp) USS Oahu

USS Oahu

(1934-1941)

_underway_at_sea_in_September_1964_(NH_107258).jpg.webp) USS Eaton (1945)

USS Eaton (1945)_off_San_Pedro%252C_California_(USA)%252C_on_5_October_1944_(19-N-72219).jpg.webp) USS St. Louis (1945)

USS St. Louis (1945)

Popular culture

- The fictional USS San Pablo, the Yangtze Patrol gunboat in Richard McKenna's well-known 1962 novel The Sand Pebbles, set in 1926, was modelled on the USS Villalobos, a 31-year-old vessel originally captured from Spain during the Spanish–American War in 1898. In many respects, it resembled design features of the later 1928 gunboats. McKenna served aboard one of these newer river gunboats a decade after the time of his novel. The 1966 film The Sand Pebbles was based on the novel.

- William Lederer, the author of the 1958 novel The Ugly American, served on the gunboat USS Tutuila around the same time as McKenna.

- Kemp Tolley, an officer who served as executive officer of the gunboat USS Tutuila in the 1930s, wrote Yangtze Patrol, a well-received history of the patrol.

- Actor Jack Warden was an enlisted sailor with the Yangtze Patrol in the late 1930s, before World War II.

See also

References

- ↑ Tolley, Kemp (2013), Yangtze Patrol: The U.S. Navy in China, Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press

- ↑ Wheeler, Dan (July 1978). "Yangtze River Patrol. River Rats Remember..." (PDF). All Hands. No. 738. United States Navy. pp. 12–15.

- ↑ Davis, Tom (March 1977). "Grains of Salt. The Yangtze Was Their Home" (PDF). All Hands. No. 722. United States Navy. pp. 14–15.

Sources

External links

- USSPanay.org Webpage concerning the Yangtze Patrol, USS Panay, and the Panay incident

- "Chinese Pirates", February 1932, Popular Mechanics

- "A Short Philatelic History of The Yangtze Patrol" by George Saqqal, Universal Ship Cancellation Society, February, March, April and May 2004 volumes of the LOG (Monthly Journal)

- The Yangtze Patrol and South China Patrol – The U.S. Navy in China: A Brief Historical Chronology

- Uniforms of the United States Navy in China 1920–1941 by Gary Joseph Cieradkowski

- Inside the Archives: The Yangtze River Patrol Collection

- Yangtze Patrol U.S. Navy 1935 (YouTube documentary video)

- Richard Crenna's The Sand Pebbles CasaQ Cookbook, Captain, (Richard Crenna) in the film, The Sand Pebbles (Yangtze Patrol – U.S. Navy Chow and Recipes)