Yazathingyan ရာဇသင်္ကြန် | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chief Minister of Ava | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 20 May 1426 – 24 July 1468 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarchs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Baya Gamani | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | ? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Co-Chief Minister of Ava | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office November 1425 – May 1426 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | Min Nyo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | ? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Baya Gamani of Singu (as Chief Minister) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | c. 1380s Ava Kingdom | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 1470s? Ava Kingdom | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | unnamed | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Pauk Hla | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Military service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Allegiance | Ava Kingdom | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Branch/service | Royal Burmese Army | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years of service | 1401–1445 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank | General | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Battles/wars |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Yazathingyan (Burmese: ရာဇသင်္ကြန်, pronounced [jàza̰ θɪ́ɴdʑàɴ]; c. 1380s–c. 1470s) was chief minister of Ava (now Upper Myanmar) from 1426 to 1468. He served over 67 years as a senior royal army officer and court minister under seven kings of Ava from Minkhaung I to Narapati I. He also held several governorships, most prominently at Sagaing (1413–1450).

His career in the royal service began soon after Minkhaung I's accession in 1400. Starting out as a cavalry battalion officer in the royal army, he fought against the southern Hanthawaddy Kingdom in the decades-long war, and rose to become part of the Ava high command as well as a senior minister at the Ava court by the mid-1410s. After the assassinations of kings Thihathu and Min Hla in 1425, he and his elder brother Baya Gamani supported the usurper Prince Min Nyo of Kale. Near the end of the ensuing civil war in 1426, Yazathingyan, in a rare break with his brother, switched sides, and became the chief minister of the incoming power, Gov. Thado of Mohnyin.

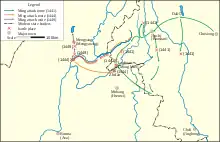

Yazathingyan led the Ava court throughout King Thado's 13-year reign but his influence over the king waned drastically towards the end of the reign. He could not stop the eccentric king from recalibrating the Burmese calendar in 1438. The chief minister fully backed Thado's successor King Minye Kyawswa's policy to forcefully regain the vassal states in revolt. He and Gamani even co-commanded an expedition that captured the rebel states of Taungdwin and Toungoo (Taungoo) in 1441. When Minye Kyawswa died without a male heir in 1442, Yazathingyan felt powerful enough to offer the throne to the late king's brother-in-law Gov. Thihapate of Mohnyin. Only when Thihapate declined the offer, did the powerful minister offer the throne to the rightful heir, the king's younger brother, who succeeded as King Narapati.

Despite his bungled attempt as kingmaker, Yazathingyan managed to retain his powerful post throughout Narapati's 26-year reign. His notable policy successes include the 1445 truce negotiations with the Chinese during the Chinese invasions, and the 1455 border demarcation treaty with Arakan between Narapati and King Min Khayi of Arakan. His last act came in 1467 when he and his son had to transport a severely wounded Narapati, who had just survived an assassination attempt, to Prome (Pyay). The old minister's long career most probably ended with the death of the king in 1468 as he is not mentioned in the royal chronicles again.

Early career

Minkhaung's reign (1400–1421)

His career began with the accession of King Minkhaung I. In late 1400 or early 1401,[note 2] the king appointed him governor of Siboktara, a small district about 100 km north of the capital Ava (Inwa), with the title of Yazathingyan, and his older brother governor of Singu, with the title of Baya Gamani.[1][2][note 3] Starting out as cavalry battalion commanders,[3] the brothers quickly rose to become regimental commanders, and participated in several military campaigns, most notably in the decades-long war against the southern Hanthawaddy Kingdom. By 1415, Yazathingyan had risen up to the Ava high command. His advice to Crown Prince Minye Kyawswa not to engage Hanthawaddy forces in Dala–Twante was famously discarded by the crown prince, who would soon fall in action in the ensuing battle.[4][5]

Yazathingyan was more than a commander. In 1408,[note 4] he not only became governor of Amyint but also joined the court led by Chief Minister Min Yaza as a junior amat (အမတ်, minister).[note 5] Then in 1413, he was promoted by the king to his most prominent post yet—as governor of Sagaing, the former royal capital across the Irrawaddy from Ava that had been held by the most senior royals. His immediate predecessor was the king's middle son Prince Thihathu, whom the king had transferred to Prome (Pyay).[6][7]

Thihathu and Min Hla years (1421–1425)

Yazathingyan retained the Sagaing post after Thihathu succeeded Minkhaung in 1421. He went to the southern front when Thihathu renewed the dormant war with Hanthawaddy in 1422.[note 6] In 1425, Yazathingyan and Gamani decided to side with the usurpers Prince Nyo of Kale and Queen Shin Bo-Me, following the assassinations of Thihathu and his son and successor Min Hla. The brothers were part of the pro-Nyo faction that also included Sawbwa Le Than Bwa of Onbaung, Gov. Thray Sithu of Myinsaing, Gov. Thinkhaya III of Toungoo, and Gov. Thihapate III of Taungdwin.[8][9] However, they faced a serious challenger in Sawbwa Thado of Mohnyin, who vehemently opposed Nyo's takeover, and went on to declare war on the Ava regime in February 1426.[10]

Succession crisis (1425–1426)

As other senior members of the court went to the front,[8][10] Baya Gamani and Yazathingyan became the de facto leaders of the Ava court.[note 7] The brothers—along with their youngest army commander brother Yan-Lo Kywe—remained by the royal couple into early May even as Thado's forces closed in, and other vassals deserted.[11][12] By mid-May, however, Yazathingyan and Yan-Lo Kywe too were wavering; they refused to go along with Gamani's plan to evacuate the couple out of Ava. In the end, only Gamani and his small battalion escorted Nyo and Bo-Me out of Ava. Yazathingyan and Yan-Lo Kywe duly surrendered,[13][14] allowing Thado to enter Ava unopposed on 16 May 1426.[note 8]

Chief Minister

Thado court (1426–1439)

Yazathingyan and the few remaining ministers were pardoned by Thado, who was eager to retain the existing administration.[15] For his part, Yazathingyan soon proved his loyalty by serving with distinction in the August 1426 campaign that captured the most senior princes of the previous dynasty—Prince Tarabya and Prince Minye Kyawhtin—in Pakhan, greatly impressing the king.[16][17] He continued to side with Thado even when Prince Minye Kyawhtin, who was pardoned by Thado, promptly fled, and raised a serious rebellion. Still, Yazathingyan could not keep his brother Gamani, who allowed himself to be captured after the death of King Nyo, out of prison. Gamani would remain in prison until late 1427 when he was asked to defend the capital region from Kyawhtin's rapidly advancing forces.[18][19]

By 1428, Yazathingyan had firmly established himself as the king's main adviser. He advised Thado to focus on consolidating the core Irrawaddy valley, and extending control to closer southeastern districts of Pinle, Yamethin and Toungoo. Thado generally followed the advice but the results were mixed. In 1429, upon Yazathingyan's recommendation, the king appointed his second son Thihathu as viceroy of Prome (Pyay) in the south, and his younger brother Nawrahta as governor of Myedu in the north, in order to defend the core region along the Irrawaddy.[20] However, Yazathingyan's attempt to divide its former vassals in the east and the southeast failed. In 1428, upon Yazathingyan's advice, Thado sent two separate missions to Onbaung and Yat Sauk Naung Mun, asking Onbaung to withdraw its support of Prince Minye Kyawhtin at Pinle, and Yat Sauk to end its support of Thinkhaya III of Toungoo, in exchange for Ava's recognition of the Shan states. Both missions failed to secure a deal.[21][22] Yazathingyan gave a similar advice in 1430 when the combined forces of the southern Hanthawaddy Kingdom and the rebel state of Toungoo laid siege to Prome. He told the king that Ava did not have enough troops to wage war on multiple fronts, and that Thado should negotiate directly with King Binnya Ran I of Hanthawaddy, and isolate Toungoo. Thado reluctantly followed the advice, and subsequent negotiations resulted in a 1431 peace treaty between Thado and Ran in which Thado agreed to cede the southernmost districts (Tharrawaddy and Paungde), and Ran agreed to end his support of Toungoo.[23][24]

However, Thado never followed through on retaking Toungoo. The court had to manage an increasingly eccentric king, who devoted much of the royal treasury to building religious buildings for the rest of his reign.[25][26] Yazathingyan was aghast when Thado famously responded to Binnya Ran's 1436 takeover of Toungoo, by ordering the recalibration of the Burmese calendar.[27] The king, upon the advice of court astrologers, had come to believe that his rump kingdom's troubles needed to be addressed by recalibrating the calendar to year 2 when the calendar reached the Year 800 ME (on 30 March 1438). Yazathingyan tried to dissuade the king by telling him that those who altered the calendar died within the year. Unmoved, Thado forced the court to implement the recalibration in 1438.[26][28]

Minye Kyawswa court (1439–1442)

Yazathingyan fully supported the new king Minye Kyawswa's policy to forcefully reclaim Ava's former vassals. He, along with his two brothers, even went to the front in the 1440–41 dry season. The campaign, initially led by the king's uncle Nawrahta I of Myedu, got off to a poor start, and turned around only after Gamani and Yazathingyan took over the overall command. The brothers captured Taungdwin, and Toungoo (Taungoo). In the battle of Toungoo, Yazathingyan, already in his 50s, slew Min Saw Oo, the ruler of Toungoo, during a close combat atop their respective war elephants, leading to the capture of Toungoo.[29][30]

The battlefield success cemented his power even more. So confident of his authority, the chief minister even attempted to play kingmaker after Minye Kyawswa's sudden death in 1442. Although the late king's younger brother Viceroy Thihathu of Prome was next in the line of succession—Minye Kyawswa did not leave a male heir—Yazathingyan's court decided to offer the throne to Sawbwa Thihapate of Mohnyin, the brother-in-law of the late king. (According to Aung-Thwin, the ministers initially chose Thihapate probably because they wished to wield greater power, knowing that Thihathu was likely to be a stronger leader than Thihapate.[31]) Because Thihapate at the time was laying siege to Mogaung, 500 km north of Ava, the ministers rushed a messenger on horseback, offering him the throne. But Thihapate rejected the offer, saying the rightful heir Thihathu should get it.[32] Only then, did the court send a royal flotilla down the Irrawaddy to Prome (Pyay) to invite Thihathu to Ava. Thihathu formally ascended to the throne with the reign name of Narapati on 6 April 1442.[33][34]

Narapati court (1442–1468)

Despite his bungled attempt to put Thihapate on the throne, Yazathingyan survived. Narapati, who had spent the last dozen years away from Ava, decided that he needed the court. Yazathingyan for his part quickly affirmed his loyalty to the new king. He went to the front with Narapati as an adviser when Chinese incursions into Ava territory began in 1443. In 1445, he advised the king to give up the renegade sawbwa Tho Ngan Bwa, whom the Chinese were after,[35][36] in exchange for the Chinese recognition of Ava's control over a northern district that Hsenwi, then a Chinese vassal state, had also claimed.[37] However, the truce did not last. The Chinese forces invaded Ava's northern territories again in 1449 although it ended in failure.[38][39])

In 1450, Yazathingyan's nearly 37-year run as governor of Sagaing ended.[note 9] Narapati appointed his son-in-law Min Phyu as governor of Sagaing and the ten northern towns,[40][38] and moved his chief minister to Amyint, a fortified town about 80km west of Sagaing.[40][41] In 1455, Yazathingyan advised Narapati to sign a peace treaty with King Min Khayi of Mrauk-U (Arakan).[42][43] The two kings met at a place called Bo Khaung Nwe Daw, and demarcated the border along the Bo Khaung range, the west of the watershed belonging to Arakan and the east to Ava.[44][45]

Yazathingyan continued to be the king's trusted adviser to the end of Narapati's reign. He was the one the king asked for when Narapati was stabbed by his grandson at the Ava Palace on 12 June 1467.[46] Upon the king's request, the old minister and his son Pauk Hla brought the wounded king and the chief queen by boat to Prome, where Narapati's middle son Thado Minsaw was governor. At Prome, he and his son tended to the royal couple until they were forced to flee back to Ava by Thado Minsaw,[47] who thought the father-son duo had too much influence over his parents.[note 10] Back in Ava, Yazathingyan advised Crown Prince Thihathura to go and see the king in Prome, which he did. The king still refused to return to Ava, and died from the wounds on 24 July 1468.[47][48]

Narapati's death was most probably the end of Yazathingyan's 67-year career. His name is not mentioned in the royal chronicles again. He may have retained his fief at Amyint as King Thihathura's appointments did not include Amyint.[note 11]

Military service

The following is a list of military campaigns in which his name is explicitly mentioned as a commander in the chronicles. Although he likely participated in the other campaigns against Hanthawaddy, and against the Chinese incursions, chronicles do not provide specific commander lists for those campaigns.

| Campaign | Duration | Troops commanded | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ava–Hanthawaddy War (1401–1403) | 1401–02 | 300 cavalry | Co-led (with his brother Baya Gamani) the Ava counterattack near Pagan (Bagan) with the cavalry in 1402.[3] |

| Conquest of Arakan | 1406 | 1 regiment | Commanded a regiment under the command of Thado and Crown Prince Minye Kyawswa[49] |

| Ava–Hanthawaddy War (1408–1408) | 1408 | 1 regiment | Commanded a regiment in the 22-regiment strong army that invaded Hanthawaddy.[50][51] Part of the delegation that tried to negotiate an ultimately unsuccessful ceasefire with the enemy.[52] |

| Ava–Hanthawaddy War (1408–1408) (Hsenwi campaign) | 1412 | 1 regiment | Commanded a regiment in Minye Kyawswa's 7000-strong army in the Hsenwi campaign[53] |

| Ava–Hanthawaddy War (1422–1423) | 1422–23 | 1 regiment | Commanded a regiment in the first invasion army led by Gov. Thado of Mohnyin[54] |

| Ava–Hanthawaddy War (1430–1431) | 1430–31 | 1 regiment | Part of the combined relief force (13,000 troops, 800 cavalry, 50 elephants) that converaged on Prome in 1431. King Thado forced Yazathingyan to arrest Smin Bayan, who was visiting Yazathingyan's camp, during the ceasefire.[55] |

| Ava civil wars Battles of Pinle, Yamethin and Taungdwin |

1433–34 | ? | Part of a small army (5000 troops, 300 cavalry, 12 elephants) that attacked Taungdwin and Toungoo. Went to the front with his brothers Baya Gamani and Yan-Lo Kywe[56] |

| Ava civil wars Battles of Taungdwin and Toungoo |

1440–41 | ? | Co-commanded (with Baya Gamani) units of the main army (7000 troops, 400 cavalry, 20 elephants) that took Taungdwin and Toungoo[29] |

| Chinese invasions | 1445 | none | Marched with King Narapati I, who commanded the combined forces of (27,000 troops, 800 cavalry, 60 elephants, 90 war boats) to Bhamo[35] |

Notes

- ↑ The only mention of the governor of Amyint before Yazathingyan's appointment was in 742 ME (1380/81) per (Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 194) and (Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 414)

- ↑ The Maha Yazawin chronicle (1724) (Maha Yazawin Vol. 1 2006: 308) says King Minkhaung appointed Yazathingyan governor of Siboktara in 764 ME (30 March 1402–29 March 1403), a year after his accession. The Yazawin Thit chronicle (1798) (Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 212) says Minkhaung made the appointment soon after his accession in 762 ME (29 March 1400–28 March 1401). The Hmannan Yazawin chronicle (1832) (Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 443) follows the Maha Yazawin's narrative. According to the inscriptional evidence, per (Than Tun 1959: 128), Minkhaung became king on 25 November 1400, which agrees with the Yazawin Thit's accession date of 762 ME (1400/01). This means the appointment probably took place in late 1400 or early 1401.

- ↑ (Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 276): They had a much younger brother, who later became a royal army commander with the nickname of "Yan-Lo Kywe" (ရန်လိုကျွဲ; lit. "Belligerent Buffalo") in the mid-1420s.

- ↑ The chronicle Maha Yazawin (1724) is inconsistent: (Maha Yazawin Vol. 2 2006: 26) says King Minkhaung appointed Yazathingyan governor of Amyint in 771 ME (30 March 1409 to 29 March 1410) but in an earlier page (Maha Yazawin Vol. 1 2006: 334) says Yazathingyan was already governor of Amyint in Kason 770 ME (29 March 1408 to 23 April 1408). The Yazawin Thit (1798) (Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 235) says the appointment took place in 770 ME (29 March 1408 to 29 March 1409), and the Hmannan Yazawin (1832) (Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 2) accepts the correction.

Furthermore, the appointment took place between 29 March 1408 and 23 April 1408 since all the chronicles (Maha Yazawin Vol. 1 2006: 334), (Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 229) and (Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 477) say Gov. Yazathingyan of Amyint was one of the commanders of the 1408 campaign that began in Kason 770 ME (29 March 1408 to 23 April 1408). - ↑ (Maha Yazawin Vol. 1 2006: 336) and (Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 479): Yazathingyan was one of the ten amats (ministers) that negotiated a ceasefire with Pegu in 1408. The 10-member delegation was led by Chief Minister Min Yaza; other members were: 2. Thihapate III of Taungdwin, 3. Thray Sithu of Myinsaing, 4. Tarabya I of Pakhan, 5. Uzana of Pagan, 6. Baya Thingyan [sic] (Nanda Thingyan of Pyinzi?), 7. Nawrahta of Salin, 8. Yazathingyan of Amyint, 9. Min Nyo of Kale, 10. Thado of Mohnyin.

- ↑ The Maha Yazawin is inconsistent: (Maha Yazawin Vol. 2 2006: 57) says Yazathingyan died in action in Dala; and the next page (Maha Yazawin Vol. 2 2006: 58) says Yazathingyan was one of the commanders of the relief force sent to the front. (Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 267) corrects that Zeya Thingyan was the commander that died in Dala in early 1422, and specifically made the point that Yazathingyan remained alive to King Narapati I's reign. Nonetheless (Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 55–56) retains Maha Yazawin's inconsistent narrative.

- ↑ All the main three chronicles—(Maha Yazawin Vol. 2 2006: 61) (Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 272), and (Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 60)—name Baya Gamani and Yazathingyan as the senior ministers of the court, with Gamani's name coming first. However, (Aung-Thwin 2017: 85) considers Yazathingyan to be more senior, "first in line was Yazathingyan, minister to the previous king" (Min Nyo), while calling Baya Gamani "one of the ministers".

- ↑ (Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 272): Thursday, the 10th waxing of Nayon 788 ME = 16 May 1426

- ↑ Various chronicles report different dates; the Hmannan Yazawin chronicle alone gives two dates, a decade a part, in two different sections. (Maha Yazawin Vol. 2 2006: 84) (1724) states that Narapati appointed Min Phyu as governor of Sagaing, and Yazathingyan as governor of Amyint in 822 ME (1460/61). (Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 290) (1798) corrects the year to 812 ME (1450/51). (Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 89) (1832) accepts 812 ME and adds that the appointment took place in or soon after Waso 812 ME (June/July 1450). However, a few pages later (Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 95) retains the Maha Yazawin account that the appointment took place in 822 ME (1460/61).

(Aung-Thwin 2017: 97) simply follows the Maha Yazawin's account, and does not mention later chronicles' accounts. - ↑ (Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 295) and (Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 98): Thado Minsaw challenged Yazathingyan to a duel on their war elephants to prove the minister's reputation as a combat fighter. Yazathingyan, who was likely in his 80s, bowed down to the prince three times without saying a word. But when Thado Minsaw did not end the taunts, Pauk Hla agreed to a duel with the condition that he be on horseback, on a horse of his choosing. The next day, Pauk Hla on horseback and Thado Minsaw on his favorite war elephant fought by the moat outside the city walls. When Pauk Hla maneuvered to get close, and maimed one of the elephant's legs, Thado Minsaw's guards then entered the fray and chased Pauk Hla, who managed to escape. Embarrassed and enraged, Thado Minsaw executed the head of his guards for failing to capture Pauk Hla.

- ↑ See (Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 297–298) and (Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 100) for Thihathura's appointments.

References

- ↑ Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 212

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 443

- 1 2 Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 455–456

- ↑ Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 256, 260

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 40, 42–43

- ↑ Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 246

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 20

- 1 2 Maha Yazawin Vol. 2 2006: 60

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 58–59

- 1 2 Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 59

- ↑ Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 271

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 60

- ↑ Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 272

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 61

- ↑ Aung-Thwin 2017: 85

- ↑ Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 273–274

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 63–64

- ↑ Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 275

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 66

- ↑ Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 277

- ↑ Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 276–277

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 3 2003: 67

- ↑ Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 279–290

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 73–74

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 75–76

- 1 2 Aung-Thwin 2017: 88

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 166

- ↑ Harvey 1925: 99

- 1 2 Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 79

- ↑ Aung-Thwin 2017: 89

- ↑ Aung-Thwin 2017: 89–90

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 81

- ↑ Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 286

- ↑ Aung-Thwin 2017: 91

- 1 2 Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 287

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 87

- ↑ Liew 1996: 185

- 1 2 Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 89

- ↑ Liew 1996: 196

- 1 2 Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 290

- ↑ Aung-Thwin 2017: 97

- ↑ Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 292

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 92–93

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 93

- ↑ Aung-Thwin 2017: 95

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 97-98

- 1 2 Aung-Thwin 2017: 98

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 98–99

- ↑ Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 224

- ↑ Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 229

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 476

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 479

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 8–9

- ↑ Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 268

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 72–73

- ↑ Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 69–70

Bibliography

- Aung-Thwin, Michael A. (2017). Myanmar in the Fifteenth Century. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-6783-6.

- Harvey, G.E. (1925). History of Burma: From the Earliest Times to 10 March 1824. London: Frank Cass & Co. Ltd.

- Kala, U (2006) [1724]. Maha Yazawin (in Burmese). Vol. 1–3 (4th printing ed.). Yangon: Ya-Pyei Publishing.

- Liew, Ming Foon (1996). "The Luchuan-Pingmian Campaigns (1436–1449) in the Light of Official Chinese Historiography". Oriens Extremus. 39 (2): 162–203. JSTOR 24047471.

- Maha Sithu (2012) [1798]. Myint Swe; Kyaw Win; Thein Hlaing (eds.). Yazawin Thit (in Burmese). Vol. 1–3 (2nd printing ed.). Yangon: Ya-Pyei Publishing.

- Royal Historical Commission of Burma (2003) [1832]. Hmannan Yazawin (in Burmese). Vol. 1–3. Yangon: Ministry of Information, Myanmar.

- Than Tun (December 1959). "History of Burma: A.D. 1300–1400". Journal of Burma Research Society. XLII (II).