Youth is an age group in the demographics of the United States. In 2010, it was estimated that 20.2% of the population of the United States were 0–14 years old (30,305,704 females and 31,639,127 males).[1]

Concerns from parents

According to a survey of parents in 2011, the issues of greatest concern about children are as follows, with percentages of adults who rate each item as a "big problem":[2]

- Childhood obesity: 33%

- Drug abuse: 33%

- Tobacco smoking: 25%

- Teen pregnancy: 24%

- Bullying: 24%

- Internet safety: 23%

- Stress: 22%

- Alcohol abuse: 20%

- Driving accidents: 20%

- Sexting: 20%

Sexuality

Adolescent sexuality in the United States relates to the sexuality of American adolescents and its place in American society, both in terms of their feelings, behaviors and development and in terms of the response of the government, educators and interested groups.

Youth rights

The National Youth Rights Association is the primary youth rights organization in the United States, with local chapters across the country and constant media exposure. The organization known as Americans for a Society Free from Age Restrictions is also an important organization. The Freechild Project has gained a reputation for interjecting youth rights issues into organizations historically focused on youth development and youth service through their consulting and training activities. The Global Youth Action Network engages young people around the world in advocating for youth rights, and Peacefire provides technology-specific support for youth rights activists.

Choose Responsibility and their successor organization, the Amethyst Initiative, founded by Dr. John McCardell Jr., exist to promote the discussion of the drinking age, specifically. Choose Responsibility focuses on promoting a legal drinking age of 18, but includes provisions such as education and licensing. The Amethyst Initiative, a collaboration of college presidents and other educators, focuses on discussion and examination of the drinking age, with specific attention paid to the culture of alcohol as it exists on college campuses and the negative impact of the drinking age on alcohol education and responsible drinking.

Youth politics

.jpg.webp)

With roots in the early youth activism of the Newsboys and Mother Jones' child labor protests at the turn of the 20th century, youth politics were first identified in American politics with the formation of the American Youth Congress in the 1930s. In the 1950s and 1960s organizations such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Students for a Democratic Society were closely associated with youth politics, despite the broad social statements of documents including the liberal Port Huron Statement and the conservative Sharon Statement and leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr. Other late-period figures associated with youth politics include Tom Hayden, Marian Wright Edelman and Bill Clinton.

Our answer is the world's hope; it is to rely on youth. The cruelties and obstacles of this swiftly changing planet will not yield to obsolete dogmas and outworn slogans. It cannot be moved by those who cling to a present which is already dying, who prefer the illusion of security to the excitement of danger. It demands the qualities of youth: not a time of life but a state of mind, a temper of the will, a quality of the imagination, a predominance of courage over timidity, of the appetite for adventure over the love of ease. - Robert F. Kennedy, South Africa, 6-6-1966

Youth vote

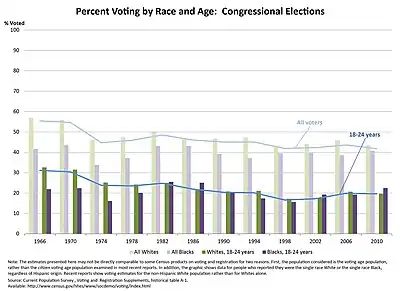

The youth vote in the United States is the cohort of 18–24 year-olds as a voting demographic,[3] though some scholars define youth voting as voters under 30.[4] Many policy areas specifically affect the youth of the United States, such as education issues and the juvenile justice system;[5] however, young people also care about issues that affect the population as a whole, such as national debt and war.[6]

Young people have the lowest turnout, though as the individual ages, turnout increases to a peak at the age of 50 and then falls again.[7]

Ever since 18-year-olds were given the right to vote in 1971 through the 26th Amendment to the Constitution,[8] youth have been under represented at the polls as of 2003.[3] In 1976, one of the first elections in which 18-year-olds were able to vote, 18–24 year-olds made up 18 percent of all eligible voters in America, but only 13 percent of the actual voters – an under-representation of one-third.[3] In the next election in 1978, youth were under-represented by 50 percent. "Seven out of ten young people…did not vote in the 1996 presidential election… 20 percent below the general turnout."[9] In 1998, out of the 13 percent of eligible youth voters in America, only five percent voted.[3] During the competitive presidential race of 2000, 36 percent of youth turned out to vote and in 2004, the "banner year in the history of youth voting," 47 percent of the American youth voted.[10] In the Democratic primaries for the 2008 U.S. presidential election, the number of youth voters tripled and even quadrupled in some states compared to the 2004 elections.[11] In 2008, Barack Obama spoke about the contributions of young people to his election campaign outside of just voter turnout.[12]Mental health

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, approximately 46% of American adolescents aged 13–18 will suffer from some form of mental disorder. About 21% will suffer from a disorder that is categorized as “severe,” meaning that the disorder impairs their daily functioning,[13] but almost two-thirds of these adolescents will not receive formal mental health support.[14] The most common types of disorders among adolescents as reported by the NIMH is anxiety disorders (including generalized anxiety disorder, phobias, post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and others), with a lifetime prevalence of about 25% in youth aged 13–18 and 6% of those cases being categorized as severe.[15] Next is mood disorders (major depressive disorder, dysthymic disorder, and/or bipolar disorder), with a lifetime prevalence of 14% and 4.7% for severe cases in adolescents.[16] A similarly common disorder is Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which is categorized as a childhood disorder but oftentimes carries through into adolescence and adulthood. The prevalence for ADHD in American adolescents is 9%, and 1.8% for severe cases.[17] It is important to understand that ADHD is a serious issue in not only children but adults. When children have ADHD a number of mental illnesses can come from that which can affect their education and hold them back from succeeding.

According to Mental Health America, more than 10% of young people exhibit symptoms of depression strong enough to severely undermine their ability to function at school, at home, or whilst managing relationships.[18]

A 2021 study conducted by NIMH managed to link 31.4% of suicide deaths to a mental health disorder, the most common ones being attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or depression.[19] Suicide was the second leading cause of death among persons aged 10–29 years in the United States during 2011–2019.[20] More teenagers and young adults die from suicide than cancer, heart disease, AIDS, birth defects, stroke, pneumonia, influenza, and chronic lung disease combined.[21] There are an average of over 3,470 attempts by students in grades 9–12.[22]

According to APA, the percentage of students going for college mental health counselling has been rising in recent years, which by report for anxiety as the most common factor, depression as the second, stress as the third, family issues as the fourth, and academic performance and relationship problems as the fifth and sixth most.[23]Juvenile delinquency

Juvenile delinquency in the United States refers to crimes committed by children or young people, particularly those under the age of eighteen (or seventeen in some states).[24]

Juvenile delinquency has been the focus of much attention since the 1950s from academics, policymakers and lawmakers. Research is mainly focused on the causes of juvenile delinquency and which strategies have successfully diminished crime rates among the youth. Though the causes are debated and controversial, much of the debate revolves around the punishment and rehabilitation of juveniles in a youth detention center or elsewhere.Child support

Child labor

Youth unemployment

The general unemployment rate in the United States has increased in the last 5 years, but the youth unemployment rate has jumped almost 10 percentage points.[25] In 2007, before the most recent recession began, youth unemployment was already at 13%. By 2008, this rate had jumped to 18% and in 2010 it had climbed to just under 21%.[26][25] The length of time the youth are unemployed has expanded as well, with many youth in the United States remaining unemployed after more than a year of searching for a job.[26] This has caused the creation of a scarred generation, as discussed below. An estimated 9.4 million young people ages 16 to 24 in the United States (12.3%) are neither working nor in school.[27] As of July 2017 an estimated 20.9 million young people ages 16 to 24 in the United States (12.3%) are employed in the United States. The unemployment rate for youth was 9.6% in July, down by 1.9 percentage points from July 2016.[28]

The demographic of unemployment among youth in the United States as of July 2017, show that the unemployment rates for both young men (10.1%) and women (9.1%) were lower than the summer before. The July 2017 rates for young Whites (8.0%) and Blacks (16.2%) declined over the year, while the rates for young Asians (9.9%) and Hispanics (10.1%) showed little change.[28] In August 2020, youth unemployment stood at 14.7%.[29]See also

- Adolescent and young adult oncology

- Demographics of the United States

- Education in the United States

- American family structure

- Child poverty in the United States

- Youth incarceration in the United States

- Street children in the United States

- Effect of World War I on children in the United States

- Childhood obesity in the United States

Other countries:

- Category:Youth by country

References

- ↑ CIA World Factbook: "CIA — The World Factbook — United States". CIA. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- ↑ 5th annual survey by C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, the University of Michigan Department of Pediatrics and Communicable Diseases, and the University of Michigan Child Health Evaluation and Research (CHEAR) Unit.

- 1 2 3 4 Iyengar, Shanto; Jackman, Simon (November 2003). "Technology and Politics: Incentives for Youth Participation". International Conference on Civic Education Research: 1–20.

- ↑ "2022 Election: Young Voters Have High Midterm Turnout, Influence Critical Races". circle.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2023-09-24.

- ↑ Sherman, Robert (Spring 2004). "The Promise of Youth is in the Present". National Civic Review. 93: 50–55. doi:10.1002/ncr.41.

- ↑ "18 in '08", Wikipedia, 2021-11-21, retrieved 2023-09-24

- ↑ Klecka, William (1971). "Applying Political Generations to the Study of Political Behavior: A Cohort Analysis". Public Opinion Quarterly. 35 (3): 369. doi:10.1086/267921.

- ↑ "Twenty-sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution", Wikipedia, 2023-08-28, retrieved 2023-09-24

- ↑ Strama, Mark (Spring 1998). "Overcoming Cynicism: Youth Participation and Electoral Politics". National Civic Review. 87 (1): 71–77. doi:10.1002/ncr.87106.

- ↑ Walker, Tobi (Spring 2006). ""Make Them Pay Attention to Us": Young Voters and the 2004 Election". National Civic Review. 95: 26–33. doi:10.1002/ncr.128.

- ↑ Harris, Chris. "Super Tuesday Youth Voter Turnout Triples, Quadruples in Some States." MTV News. retrieved 6 Feb 2008.

- ↑ Rankin, David. (2013). US Politics and Generation Y : Engaging the Millennials. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 978-1-62637-875-9. OCLC 1111449559.

- ↑ "Any Disorder Among Children". National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- ↑ "Youth Mental Health and Academic Achievement" (PDF). National Center for Mental Health Checkups at Columbia University. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ↑ "Any Anxiety Disorder Among Children". National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- ↑ "Any Mood Disorder Among Children". National Institute of Mental Health. Archived from the original on October 15, 2014. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- ↑ "Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Among Children". National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- ↑ "The State of Mental Health in America". Mental Health America. Retrieved 2023-10-28.

- ↑ "Understanding the Characteristics of Suicide in Young Children". National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). 14 December 2021. Retrieved 2022-03-22.

- ↑ Bitsko RH, Claussen AH, Lichstein J, Black LI, Jones SE, Danielson ML, et al. (February 2022). "Mental Health Surveillance Among Children - United States, 2013-2019". MMWR Supplements. 71 (2): 1–42. doi:10.15585/mmwr.su7102a1. PMC 8890771. PMID 35202359.

- ↑ "Facts & Stats". The Jason Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2022-03-24.

- ↑ "Youth Suicide Statistics". Parent Resource Program. Jason Foundation. Retrieved November 18, 2017.

- ↑ Winerman L. "By the Numbers: Stress on Campus". Monitor on Psychology. American Psychological Association. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ↑ "Statistical Briefing Book". ojjdp.gov.

- 1 2 "Youth unemployment rate, aged 15-24, men". United Nations Statistic Division. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

- 1 2 Morsy, Hanan (2012). "Scarred Generation". Finance and Development. 49 (1). Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ↑ Sarah Burd-Sharps and Kristen Lewis. Promising Gains, Persistent Gaps: Youth Disconnection in America Archived 28 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine. 2017. Measure of America of the Social Science Research Council.

- 1 2 "EMPLOYMENT AND UNEMPLOYMENT AMONG YOUTH—SUMMER 2017" (PDF). US Bureau of Labor Statistics. 16 August 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ "Youth unemployment rate". Competitiveness and Private Sector Development. 2016-02-26. doi:10.1787/9789264250529-graph204-en. ISBN 9789264250512. ISSN 2076-5762.

.svg.png.webp)