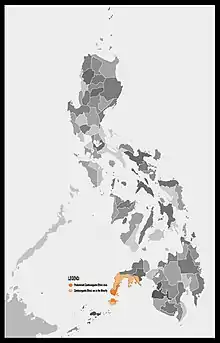

Geographic extent of the Zamboangueño people | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 3.5 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

(Zamboanga City, Zamboanga Peninsula, Basilan, Sulu, Tawi-Tawi, Metro Manila) | |

| Languages | |

| Chavacano, Spanish, Filipino, English | |

| Religion | |

| predominantly Christianity (Roman Catholic majority and Protestant minority), Islam, Paganism, others |

The Zamboangueño people (Chavacano: Pueblo Zamboangueño), are a creole ethnolinguistic nation of the Philippines originating in Zamboanga City. Spanish censuses records previously showed that as much as one-third of the inhabitants of the city of Zamboanga possess varying degrees of Iberian and Hispanic-American admixture.[1] In addition to this, select cities such as Iloilo, Bacolod, Dumaguete, Cebu, and Cavite, which were home to military fortifications and/or commercial ports during the Spanish era also hold sizable mestizo communities.[2]

The Zamboangueño nation constitute an authentic and distinct ethnolinguistic identity because of their coherent cultural and historical heritage, most notably Chavacano, that distinguishes them from neighboring ethnolinguistic nations. As a result of Spanish colonization, according to a genetic study written by Maxmilian Larena, published in the 2021 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States, the Philippine ethnic groups with the highest amount of Spanish/European descent are the Zamboangueño, with 4 out of 10 Zamboangueños being of Spanish descent (40% of the population), this is followed by Bicolanos, with 2 out of 10 Bicolanos being of Spanish descent (20% of the population). Meanwhile, there are "some" Spanish descended people among the other lowland Christianized Filipino ethnic groups.[3]

Ethnogenesis

People from other ethnolinguistic nations came to Zamboanga when the construction of the present-day Fort Pilar began. The colonial Spanish government ordered the construction of a military fort to guard off the city from Moro pirates and slave raiders of Sulu. Labourers from Panay, Cavite, Cebu, Bohol, Negros and other islands were brought to the city to help build the fort.

Eventually, these people settled in the city to live alongside and intermarried with other ethnolinguistic nations, primarily among the Subanon ethnic group, whose entire ethnicity descended from one clan is a grand claim. (from the Royal ethnic lineage of Macombong and Tongab whose father is Shariff Bungsu of Bruneian royalty and mother is Princess Nayac, the daughter of the late King of Kingdom of Jambangan, Datu Timuay of the Subanon people who are the ancestors together with other ethnolinguistic nation - the Lutao,). Together, they would form the nucleus of the present-day Zamboangueño people. To this nucleus were added the descendants of laborers from Iloilo City in Panay and of soldiers from New Spain[4] and Peru.[5]

Through intermarriage, Visayans, Hispano-Americans and with the Spanish, they created a new culture which gradually developed a distinct identity—the Zamboangueños (Zamboangueño: magá/maná Zamboangueños; Spanish: Zamboangueños). Furthermore, because these people come from different islands and even nations and spoke different languages, they together developed a new pidgin language called Chavacano. Chavacano then evolved into a full-fledged Spanish-based creole to become the lingua franca of Zamboanga City and then the official language of the Republic of Zamboanga.

Culture

The character of the Zamboangueño people are unique as we can say for their kinship family system, love for one's cultural heritage, propensity for extravagance, fiestas and siestas, as well as aristocratic behaviour. While their social lives usually revolve around religious practices, the tradition of the bantayanon and fondas, includes their bailes the vals, regodon and paso doble. They are mostly devout Roman Catholics.

The Zamboangueños of Basilan have, of late, also acquired more globalized tastes in cuisine, fashion, and customs.

Language

Chavacano is the native language of the Zamboangueño people. A conglomeration of 90% traditional Spanish and 10% influences from other Romance languages such as French, Portuguese, Italian and Native American such as Nahuatl, Taíno, Quechua et al. and Austronesian languages such as Binisaya (mainly Cebuano and Ilonggo), Tagalog, Subanon, Tausūg, Yakan, Sama and Malay.[6]

Courtship etiquette

Zamboangueño courtship traditions are elaborate and regulated by a long list of required social graces. For example, a perfectly respectable Zamboangueño gentleman (caballero) would not sit unless permitted to do so by the woman's parents, he then had to endure questions pertaining to his lineage, credentials and occupation. Finally, the courtship curfew and the need to cultivate the goodwill of all the members of the woman's family were paramount considerations before any headway could be made in pursuing a Zamboangueño señorita’s hand in marriage.

Dance

Zamboangueño songs and dances are derived primarily from Iberian performances. Specifically, the jota zamboangueña, a Zamboangueño version of the quick-stepping flamenco with bamboo clappers in lieu of Spanish castanets, are regularly presented during fiestas and formal tertulias or other Zamboangueño festivities.

Clothing

Likewise, Zamboangueño traditional costumes are closely associated with Spanish formal dress. Men wear close-necked jackets as they called camiseta Zamboangueña, de bastón pants, and European style shoes, complete with the de-rigueur bigotillos (mustache). Zamboangueño women claim ownership of the mascota, a formal gown with a fitting bodice, her shoulders draped demurely by a luxuriously embroidered, though stiff, pañuelo and fastened at the breast by a brooch or a medal. The skirt tapers down from the waist but continues on to an extended trail called the cola. The cola may be held on one hand as the lady walks around, or it may likewise by pinned on the waist or slipped up a cord (belt) that holds the dainty abanico or purse. The traditional Zamboangueño dress has been limited to formal functions, replaced by the more common shirt, denim jeans, and sneakers for men, and shirts, blouses, skirts or pants, and heeled shoes for women.

Festivals

There are several important events of the festival that can be witnessed during Holy Week (Chavacano/Spanish: Semana Santa). These include watching films (magá película) about Jesus and his teachings, visitaiglesias, processions, novenas and the climbing and praying of the Stations of the Cross (Estaciones de la Cruz) in Mt. Pulong Bato, Fiesta de Pilar (Spanish: Fiesta del Pilar), a festivity in honour of Our Lady of the Pillar (Zamboangueño: Nuestro Señora de Pilar; Spanish: Nuestra Señora del Pilar) and Zamboanga Day (Día de Zamboanga) and Day of the Zamboangueños (Día del magá Zamboangueño) which is celebrated every August 15 every year for the foundation of Zamboanga and ethnogenesis of the Zamboangueño people on August 15, 1635.

Zamboangueño celebrate Christmas in so many unique ways such as the villancicos/aguinaldos o pastores this also includes the Día de Navideña and Nochebuena, fiestas, vísperas, Diana, Misa, magá juego, processions and feasting.

Cuisine

Zamboangueño cuisine includes in its repertoire curacha, calamares, tamales, locón, cangrejos, paella, estofado, arroz a la valenciana, caldo de vaca/cerdo/pollo, puchero, caldo de arroz, lechón, jamonadas, endulzados, embutido, adobo, afritadas, menudo, caldereta, jumbá, Leche Flan and many more.

Notable persons

There are Zamboangueños who are famous for their fields of endeavor, especially in music, entertainment, sports, and politics. These are the following:

- Empress Schuck – Actress, Model, Fashion designer

- Ruby Moreno

- Frank L. Anderson (born January 19, 1957) is an American animator, director, author, and musician.

- Alyssa Alano is a Filipina – Australian film and TV actress. She was a former member of the popular Viva Hotbabes franchise.

- César Ruiz Aquino is a Filipino poet and fictionist.

- Mark Barroca is a Filipino professional basketball player who currently plays for the Star Hotshots in the Philippine Basketball Association. He currently wears the number 14 to imply the birthday of his wife.[7]

- Chris Cayzer – Aficionado Perfumes model and singer, who had his first concert in Zamboanga in July 2007 with Lovi Poe, another Aficionado model, and singer/actress. His Zamboangueño parents were based in Australia, where he grew up.

- Carlos Camins y Hernandez (November 4, 1887 – August 11, 1970) was the former governor of the old Zamboanga Province from 1931 to 1934.

- Chezka Centeno (born June 30, 1999)[8] is a Filipina billiards player from Zamboanga City.[9]

- George Christian T. Chia (born August 19, 1979), better known as Gec Chia, is a Filipino business executive and former professional basketball player.

- Armarie "Arms" Cruz – one of the "Final 12" and the lone Mindanao bet of Philippine Idol First Season.

- A. Z. Jolicco Cuadra (May 24, 1939 in Zamboanga City – April 30, 2013 in Calamba) was a poet and artist, art critic, essayist, and short story writer. He was known as the "enfant terrible of Philippine art" in the 1960s, and his good looks and writings dubbed him the Byron of Philippine literature.

- Hidilyn Diaz[10] (born February 20, 1991) is a Filipino weightlifter. She competed in the 2008 Summer Olympics and was also the youngest competitor in the women's 58-kg category in that same Olympics.[11] She was a bronze medalist in the 2007 SEA Games in Thailand and achieved tenth place at the 2006 Asian Games in the 53-kilogram class. A student of the Universidad de Zamboanga, she also won two golds and one silver in the Asian Youth/Junior Weightlifting Championship held in Jeonju, South Korea.[12] She competed in the 2016 RIO Olympics, and won second Place.

- Rexel Ryan Fabriga (born October 2, 1985) is a diver who hails from Zamboanga, Philippines.

- Eddie Rodriguez (August 23, 1932 – October 12, 2001) better known as his stage name Eddie Rodriguez was a Filipino film actor and director.

- Ryan Roose "RR" Garcia is a Filipino professional basketball player currently playing for the Star Hotshots of the Philippine Basketball Association. He was selected sixth overall in the 2013 PBA draft by the GlobalPort Batang Pier.

- Carlo Crisanto Gardo Gonzalez (born August 2, 1990, in Zamboanga City, Philippines), better known for his stage name Carlo Gonzales, is a Filipino actor who lost to despite in Survivor Philippines: Celebrity Doubles Showdown.[13][14]

- Roberto Gomez – World Pool nine ball 2007 runner-up. Beaten By Daryl Peach onto the finals 17–15.

- Winner Jumalon is a multi-award-winning Filipino contemporary visual artist based in Manila. His works of oil and encaustic on canvas have been described as "late capitalist masterpieces marred by illogical marks, haze, and aggregations of reality that not only displaces portraiture as the totemic symbols of power and status but questions the formation of identity itself as the trap where man cannot go forward".[15]

- Rudy B. Lingganay Jr. (born August 15, 1986, in Zamboanga City) is a Filipino professional basketball player who last played for the NLEX Road Warriors of the Philippine Basketball Association (PBA).[16]

- Ruru Madrid is a Filipino teen actor who rose to fame in Protégé: The Battle For The Big Artista Break.[17] He is currently seen on the GMA Network.[18] Madrid is fluent in Tagalog and English.

- Alfonso R. Márquez[19] (born March 29, 1938), better known as Alfonso "Boy" Marquez, is a Filipino former basketball player and coach. Marquez was born in Zamboanga City, Philippines.

- Christian Morones is a teen housemate in Pinoy Big Brother: Lucky 7. He's dubbed as the Courtside Kusinero of Zamboanga because of him being a varsity basketball athlete on his school as well as being fond of cooking. Kusinero is a Filipino word for Chef.

- Yong Muhajil is a teen housemate in Pinoy Big Brother: Lucky 7. Dubbed as the “Pag-A-Son ng Angkan ng Zamboanga”, likes to help his family do household chores such as to cook and to fetch water.

- Alberto Nogar – (weightlifter) bronze medalist 1958 third Asian Games Tokyo, Japan, fifth place 1958 World Weightlifting Championship Stockholm, Sweden, eighth place 1960 Rome Olympiad, 1960 Philippine Sportswriters Association Weightlifter of the Year

- Mario O'Hara[20] (April 20, 1946[21] – June 26, 2012) was an award-winning Filipino film director, film producer and screenwriter known for his sense of realism often with dark but realistic social messages.[22]

- Pres Romanillos was a Hollywood animator who had a long and successful career at studios such as DreamWorks and Walt Disney. He was responsible for breathing life into many memorable animated characters including the Native American Little Creek in DreamWorks' Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron, Pocahontas, and the villainous Hun Shan-Yu in Disney's Mulan.

- Harry Tañamor (born August 20, 1977) is an amateur boxer from Zamboanga City, Philippines best known to medal repeatedly on the world stage at light flyweight.

- Simeon Toribio – Filipino High Jumper, 1932 Olympics Bronze Medallist in Athletics. He later settled in Bohol and represented it in Congress.

- Mark Villon is a Filipino international footballer who plays as a defender for Manila Jeepney F.C. Villon previously played for San Beda College and made his international debut in 2002.

- Buddy Zabala is the bassist of Filipino new wave band The Dawn, Punk rock band Hilera, Indie band Cambio, and widely known as the bassist of the formerly disbanded and now reunited alternative rock band, the Eraserheads.[23]

References

- ↑ Jagor, Fëdor, et al. (1870). The Former Philippines thru Foreign Eyes

- ↑ Institute for Human Genetics, University of California San Francisco (2015). ""Self-identified East Asian nationalities correlated with genetic clustering, consistent with extensive endogamy. Individuals of mixed East Asian-European genetic ancestry were easily identified; we also observed a modest amount of European genetic ancestry in individuals self-identified as Filipinos"

- ↑ Maximilian Larena (January 21, 2021). "Supplementary Information for Multiple migrations to the Philippines during the last 50,000 years (Page 35)" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. p. 35. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ↑ Letter from Fajardo to Felipe III From Manila, August 15, 1620.(From the Spanish Archives of the Indies) ("The infantry does not amount to two hundred men, in three companies. If these men were that number and Spaniards, it would not be so bad; but, although I have not seen them, because they have not yet arrived here, I am told that they are, as at other times, for the most part,boys, mestizos, and mulattoes, with some Indians. There is no little cause for regret in the great sums that reënforcements of such men waste for, and cost, your Majesty. I cannot see what betterment there will be until your Majesty shall provide it, since I do not think, that more can be done in Nueva España, although the viceroy must be endeavoring to do so, as he is ordered.")

- ↑ "SECOND BOOK OF THE SECOND PART OF THE CONQUESTS OF THE FILIPINAS ISLANDS, AND CHRONICLE OF THE RELIGIOUS OF OUR FATHER, ST. AUGUSTINE" (Zamboanga City History) "He (Governor Don Sebastían Hurtado de Corcuera) brought a great reënforcement of soldiers, many of them from Perú, as he made his voyage to Acapulco from that kingdom."

- ↑ "El Torno Chabacano". Instituto Cervantes.

- ↑ Badua, Snow (April 18, 2014). "There's a story behind every jersey number. Find out what No. 14 meant to San Mig guard Mark Barroca". Spin.ph. Retrieved December 4, 2015.

- ↑ "(Billiards and Snooker) Biography Overview: CENTENO Chezka". 28th SEA Games 2015.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ Padilla, Jaime (June 9, 2015). "Chezka Centeno: The 15 year old Cueist Sensation". 28th SEA Games Singapore 2015. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- ↑ "Athlete Biography: DIAZ Hidilyn". Beijing2008.cn. The Beijing Organizing Committee for the Games of the XXIX Olympiad. Archived from the original on August 10, 2008.

- ↑ "15 Filipinos battle odds, Olympic gold 'curse'". Inquirer.net. August 9, 2008. Archived from the original on August 13, 2008.

- ↑ "City commends Zamboangueño weightlifters". Archived from the original on December 20, 2008. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- ↑ "BT: Castaways sa Survivor PHL: Celebrity Doubles Showdown". Retrieved October 26, 2011.

- ↑ "Newcomer Carlo Gonzalez considers cousin Dingdong Dantes his mentor in showbiz".

- ↑ "The Spectacular Mid Year Auction 2015" (PDF). leon-gallery.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- ↑ "Lingganay layup lifts Powerade". Philippine Daily Inquirer. September 25, 2011. Retrieved August 4, 2012.

- ↑ Paroa Pinoy Exchange

- ↑ Ruru Madrid Official Fan Page

- ↑ Evans, Hilary; Gjerde, Arild; Heijmans, Jeroen; Mallon, Bill; et al. "Alfonso Márquez". Olympics at Sports-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Archived from the original on December 3, 2016.

- ↑ Vera, Noel (June 28, 2012). "The Quiet Man Passes". Business World Philippines. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ↑ "Mario O'Hara: First an actor, second a writer, and lastly a director". June 28, 2012. Archived from the original on July 5, 2012. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- ↑ "O'Hara profile". Archived from the original on September 18, 2010.

- ↑ "Established rockers form new group". Manila Bulletin Publishing Corporation. January 11, 2010. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

External links

- Zamboanga City, Daily at the Wayback Machine (archived May 12, 2016)

- Zamboanga Online News

- The Official Website of Zamboanga Today Newspaper