| Smithsonite | |

|---|---|

| |

| General | |

| Category | Carbonate mineral |

| Formula (repeating unit) | ZnCO3 |

| IMA symbol | Smt[1] |

| Strunz classification | 5.AB.05 |

| Crystal system | Trigonal |

| Crystal class | Hexagonal scalenohedral (3m) H-M symbol: (3 2/m) |

| Space group | R3c |

| Unit cell | a = 4.6526(7) c = 15.0257(22) [Å]; Z = 6 |

| Identification | |

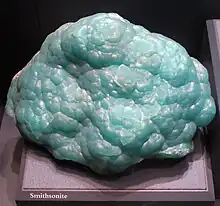

| Color | White, grey, yellow, green to apple-green, blue, pink, purple, bluish grey, and brown |

| Crystal habit | Uncommon as crystals, typically botryoidal, reniform, spherulitic; stalactitic, earthy, compact massive |

| Twinning | None observed |

| Cleavage | Perfect on [1011] |

| Fracture | Uneven, sub-conchoidal |

| Tenacity | Brittle |

| Mohs scale hardness | 4.5 |

| Luster | Vitreous, may be pearly |

| Streak | White |

| Diaphaneity | Translucent |

| Specific gravity | 4.4–4.5 |

| Optical properties | Uniaxial (−) |

| Refractive index | nω = 1.842 – 1.850 nε = 1.619 – 1.623 |

| Birefringence | δ = 0.223 – 0.227 |

| Ultraviolet fluorescence | May fluoresce pale green or pale blue under UV |

| References | [2][3][4] |

Smithsonite, also known as zinc spar, is the mineral form of zinc carbonate (ZnCO3). Historically, smithsonite was identified with hemimorphite before it was realized that they were two different minerals. The two minerals are very similar in appearance and the term calamine has been used for both, leading to some confusion. The distinct mineral smithsonite was named in 1832 by François Sulpice Beudant in honor of English chemist and mineralogist James Smithson (c. 1765–1829), who first identified the mineral in 1802.[3][5]

Smithsonite is a variably colored trigonal mineral which only rarely is found in well formed crystals. The typical habit is as earthy botryoidal masses. It has a Mohs hardness of 4.5 and a specific gravity of 4.4 to 4.5.

Smithsonite occurs as a secondary mineral in the weathering or oxidation zone of zinc-bearing ore deposits. It sometimes occurs as replacement bodies in carbonate rocks and as such may constitute zinc ore. It commonly occurs in association with hemimorphite, willemite, hydrozincite, cerussite, malachite, azurite, aurichalcite and anglesite. It forms two limited solid solution series, with substitution of manganese leading to rhodochrosite, and with iron, leading to siderite.[4] A variety rich in cadmium, which gives it a bright yellow color, is sometimes called turkey fat ore.[2]

Gallery

Crystals of smithsonite: Ojuela Mine, Mapimi, Mun. de Mapimi, Durango, Mexico

Crystals of smithsonite: Ojuela Mine, Mapimi, Mun. de Mapimi, Durango, Mexico Crystals of pink Cobaltoan smithsonite on matrix

Crystals of pink Cobaltoan smithsonite on matrix Apple-green Cuprian smithsonite crystals. A second generation of drusy smithsonite was deposited in the crevasses between the larger growth

Apple-green Cuprian smithsonite crystals. A second generation of drusy smithsonite was deposited in the crevasses between the larger growth Crystals of slightly pink cobaltoan smithsonite, Tsumeb, 6.8 x 4.6 x 3.7 cm

Crystals of slightly pink cobaltoan smithsonite, Tsumeb, 6.8 x 4.6 x 3.7 cm Blue smithsonite from the Kelly Mine in New Mexico

Blue smithsonite from the Kelly Mine in New Mexico

See also

References

- ↑ Warr, L.N. (2021). "IMA–CNMNC approved mineral symbols". Mineralogical Magazine. 85 (3): 291–320. Bibcode:2021MinM...85..291W. doi:10.1180/mgm.2021.43. S2CID 235729616.

- 1 2 Smithsonite: Smithsonite mineral information and data from Mindat

- 1 2 Smithsonite mineral data from Webmineral

- 1 2 Anthony, John W.; Bideaux, Richard A.; Bladh, Kenneth W.; Nichols, Monte C. (2005). "Smithsonite" (PDF). Handbook of Mineralogy. Mineral Data Publishing. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ↑ "Smithsonite at the National Museum of Natural History". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

Bibliography

- Tom Hughes, Suzanne Liebetrau, and Gloria Staebler, eds. (2010). Smithsonite: Think Zinc! Denver, CO: Lithographie ISBN 978-0-9790998-6-1.

- Ewing, Heather (2007). The Lost World of James Smithson: Science, Revolution, and the Birth of the Smithsonian. London and New York: Bloomsbury ISBN 978-1-59691-029-4