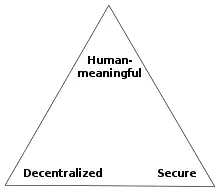

Zooko's triangle is a trilemma of three properties that some people consider desirable for names of participants in a network protocol:[1]

- Human-meaningful: Meaningful and memorable (low-entropy) names are provided to the users.

- Secure: The amount of damage a malicious entity can inflict on the system should be as low as possible.

- Decentralized: Names correctly resolve to their respective entities without the use of a central authority or service.

Overview

Zooko Wilcox-O'Hearn conjectured that no single kind of name can achieve more than two. For example: DNSSec offers a human-meaningful, secure naming scheme, but is not decentralized as it relies on trusted root-servers; .onion addresses and bitcoin addresses are secure and decentralized but not human-meaningful; and I2P uses name translation services which are secure (as they run locally) and provide human-meaningful names - but fail to provide unique entities when used globally in a decentralised network without authorities.[lower-alpha 1]

Solutions

Several systems that exhibit all three properties of Zooko's triangle include:

- Computer scientist Nick Szabo's paper "Secure Property Titles with Owner Authority" illustrated that all three properties can be achieved up to the limits of Byzantine fault tolerance.[2]

- Activist Aaron Swartz described a naming system based on Bitcoin employing Bitcoin's distributed blockchain as a proof-of-work to establish consensus of domain name ownership.[3] These systems remain vulnerable to Sybil attack,[4] but are secure under Byzantine assumptions.

- Theoretician Curtis Yarvin implemented a decentralized version of IP addresses in Urbit that hash to four-syllable, human-readable names.[5]

Several platforms implement refutations of Zooko's conjecture, including: Twister (which use Swartz' system with a bitcoin-like system), Blockstack (separate blockchain), Namecoin (separate blockchain), LBRY (separate blockchain - content discovery, ownership, and peer-to-peer file-sharing), Monero, OpenAlias,[6] Ethereum Name Service, and the Handshake Protocol.[7]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Zooko Wilcox-O'Hearn has since deleted the original blogpost

References

- ↑ Zooko Wilcox-O'Hearn. "Names: Decentralized, Secure, Human-Meaningful: Choose Two". Archived from the original on 20 October 2001.

- ↑ Nick Szabo, Secure Property Titles Archived 24 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine, 1998

- ↑ Aaron Swartz, Squaring the Triangle: Secure, Decentralized, Human-Readable Names Archived 15 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Aaron Swartz, 6 January 2011

- ↑ Dan Kaminsky, Spelunking the Triangle: Exploring Aaron Swartz’s Take On Zooko’s Triangle Archived 16 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, 13 January 2011

- ↑ Curtis Yarvin: Urbit- A Clean Slate Functional Operating Stack - λC 2016, retrieved 9 July 2022

- ↑ Monero core team (19 September 2014). "OpenAlias". Archived from the original on 11 February 2015. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ↑ Director of The Handshake Project (12 July 2021). "Handshake". Archived from the original on 25 August 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

External links

- Zooko Wilcox-O'Hearn, Names: Decentralized, Secure, Human-Meaningful: Choose Two – the essay highlighting this difficulty

- Marc Stiegler, An Introduction to Petname Systems – a clear introduction

- Nick Szabo, Secure Property Titles – argues that all three properties can be achieved up to the limits of Byzantine fault tolerance.

- Bob Wyman, The Persistence of Identity (Updating Zooko's Pyramid)

- Paul Crowley, Squaring Zooko's Triangle

- Aaron Swartz, Squaring the Triangle using a technique from Bitcoin